THE

MENORAH

JOURNAL

|

Greetings: From Dr. Cyrus Adler, Louis D. Brandeis,

Professor Richard Gottheil, Dr. Joseph Jacobs, Dr.

Kaufman Kohler, Justice Irving Lehman, Judge Julian W.

Mack, Dr. J. L. Magnes, Dr. Martin A. Meyer, Dr. David

Philipson, Dr. Solomon Schechter, Jacob H. Schiff, and

Dr. Stephen S. Wise

| A Call to the Educated Jew | Louis D. Brandeis |

| Menorah: A Poem | William Ellery Leonard |

| The Jews in the War | Joseph Jacobs |

| Jewish Students in European Universities | Harry Wolfson |

| The Twilight of Hebraic Culture | Max L. Margolis |

| Days of Disillusionment | Samuel Strauss |

Three University Addresses—President Arthur T. Hadley of Yale University,

Chancellor Elmer E. Brown of New York University,

President Charles W. Dabney of the University of Cincinnati |

| The Menorah Movement | Henry Hurwitz |

| From College and University: Reports from Menorah Societies |

|

|

PUBLISHED BY THE INTERCOLLEGIATE MENORAH ASSOCIATION

600 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK -:- -:- -:- 25 CTS. A COPY

INTERCOLLEGIATE MENORAH

ASSOCIATION

For the Study and Advancement of

Jewish Culture and Ideals

OFFICERS

Chancellor

HENRY HURWITZ

600 Madison Avenue, New York

President

I. LEO SHARFMAN

University of Michigan

First Vice-President

MOSES BARRON

University of Minnesota

|

Second Vice-President

LEON J. ROSENTHAL

Cornell University

|

Secretary

ISADOR BECKER

University of Michigan

|

Treasurer

J. K. MILLER

Penn State College

|

THE ADMINISTRATIVE COUNCIL

Composed of Representatives, one each, from every constituent Menorah

Society (The Representatives for 1915 will be announced in the next

issue of The Menorah Journal)

There are Menorah Societies now at the following Colleges and

Universities:

| Boston University | University of Colorado |

| Brown University | University of Denver |

| Clark University | University of Illinois |

| College of City of New York | University of Maine |

| Columbia University | University of Michigan |

| Cornell University | University of Minnesota |

| Harvard University | University of Missouri |

| Hunter College | University of North Carolina |

| Johns Hopkins University | University of Omaha |

| New York University | University of Pennsylvania |

| Ohio State University | University of Pittsburgh |

| Penn State College | University of Texas |

| Radcliffe College | University of Washington |

| Rutgers College | University of Wisconsin |

| Tufts College | Valparaiso University |

| University of California | Western Reserve University |

| University of Chicago | Yale University |

| University of Cincinnati |

Office of the Intercollegiate Menorah Association

600 Madison Avenue, New York

[1]

the

Menorah Journal

VOLUME I JANUARY, 1915 NUMBER 1

An Editorial Statement

THE MENORAH JOURNAL, in its efforts to carry forward the aims and

aspirations of the Menorah movement, will necessarily be far more than

merely an "official organ" for the Menorah Societies. That function,

indeed, becomes increasingly important as the Menorah Societies

multiply in number and influence throughout the country. In this

special appeal to Menorah members, however, the Journal will be more

than a news medium; it will supply important material for study and

discussion, and stimulate thinking and active effort in behalf of

Menorah ideals. And inasmuch as the furtherance of Menorah ideals

means the advancement of American Jewry and the spread of Hebraic

culture, the Journal should appeal to every one in America who

sympathises with these purposes. The Journal will be conducted with

this general appeal always in mind—with the desire, indeed, to make

it a model publication dealing with Jewish life and thought. To

publish a periodical that shall measure up to this high standard, with

its accompanying influence and power, is one of the aspirations of the

Menorah movement; and the Menorah auspices and conditions are so

peculiarly favorable to the achievement of this ambition as to lend

every encouragement to the effort that will be put forth to make the

Journal a genuinely significant publication for the whole of American

Jewry.

For conceived as it is and nurtured as it must continue to be in the

spirit that gave birth to the Menorah idea, the Menorah Journal is

under compulsion to be absolutely non-partisan, an expression of all

that is best in Judaism and not merely of some particular sect or

school or locality or group of special interests; fearless in telling

the truth; promoting constructive thought rather than aimless

controversy; animated with the vitality and enthusiasm of youth;

harking back to the past that we may deal more wisely with the present

and the future; recording and appreciating Jewish achievement, not to

brag, but to bestir ourselves to emulation and to deepen the

consciousness of noblesse oblige; striving always to be sane and

level-headed; offering no opinions[2] of its own, but providing an

orderly platform for the discussion of mooted questions that really

matter; dedicated first and foremost to the fostering of the Jewish

"humanities" and the furthering of their influence as a spur to human

service.

It will undoubtedly prove necessary on more than one occasion in the

future to emphasize again the fact that the Journal is an

unqualifiedly non-partisan forum for the discussion of Jewish

problems; and that accordingly neither the Menorah Journal nor the

Menorah Societies are to be regarded as standing sponsor for the views

expressed in these columns by contributors. Nor will the Journal have

any editorials expressing the views of its editors or of the Menorah

organization,—particularly since the Menorah organization takes no

official stand on mooted subjects. The editorial policy will be one of

fairness in giving equal hospitality to opposing views; and space will

gladly be given to reasonable letters or articles that take exception

to statements or opinions published in these pages.

The Journal is singularly fortunate in having enlisted the

co-operation of the distinguished leaders of Jewish life and thought

who comprise its Board of Consulting Editors. The assurances already

in hand of important articles to come from our Consulting Editors and

from other notable men and women, both Jewish and non-Jewish, lend

strength to the editorial confidence that succeeding issues will more

and more repay the public interest. As an incidental but none the less

vital aim, the Journal hopes to be instrumental in encouraging our

young men and women, particularly in the Menorah membership, to devote

themselves to Jewish subjects as worthy of their best literary

effort,—with publication in the Menorah Journal as a prize to be

eagerly sought for. The Menorah hopes through the incentive of the

Journal to develop a "new school" of writers on Jewish topics that

shall be distinguished by the thoroughness and clarity of the

university-trained mind and inspired by the youthful, searching,

unfearing spirit of the Menorah movement.

With these aims and these aspirations, the Menorah Journal bids for

the favor of the public. Scholarly when scholarship will be in order,

but always endeavoring to be timely, vivacious, readable; keen in the

pursuit of truth wherever its source and whatever the consequences; a

Jewish forum open to all sides; devoted first and last to bringing out

the values of Jewish culture and ideals, of Hebraism and of Judaism,

and striving for their advancement—the Menorah Journal hopes not

merely to entertain, but to enlighten, in a time when knowledge,

thought, and vision are more than ever imperative in Jewish life.[3]

Greetings

From Dr. Cyrus Adler

President of the Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning,

Philadelphia

I AM very glad to be able through this first number of your Journal to

send a word of greeting to the Menorah men throughout the United

States. An Association which has as its object the promotion in

American colleges and universities of the study of Jewish history,

culture and problems, and the advancement of Jewish ideals, cannot but

fail to command my personal and official interest and support.

The Jewish people have a long and honorable record of literary

activity. Our Holy Scriptures, our Rabbinical Literature, our

contributions to philosophy, to ethics, to law, our poetry, sacred and

secular, our share in the world's history, all become part of the

program which you have laid out for yourselves as a means of

cultivation. In their due proportion they should (although they do

not) form a part of the outfit of every educated man. That they should

be especially cultivated by Jewish young people is self-evident, and,

for several thousand years, they have been.

You Menorah men have taken the modern form of association for the

purpose of carrying on these studies, of cherishing your Jewish ideals

along with your general culture or with your chosen profession, and it

was high time that you should do so. You already count thousands of

young people, and as time goes on you will gradually increase in

number. From among your group will come the future leaders of the

Jewish people in America, and your main body will form our

intellectual backbone. It is my hope and belief that your movement

will gradually tend toward the maintenance and promotion of Judaism in

this land.

We are now a population of nearly three million souls. That such a

vast body should be lost to Judaism or should maintain a Judaism

ignorant of its language, its literature or its traditions, is almost

unthinkable. Conditions abroad may shift the center of gravity of

Judaism and of Jewish learning to the American continent. Your

movement is one which will aid in training the group that may be

expected to measure up to our new responsibilities.

It has been a source of great personal pleasure to me to meet with

your Association in your annual convention and to have the privilege

of coming in personal contact with some of your Societies,—at

Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Pennsylvania, and Boston Universities. I hope

to have the pleasure of meeting more of you and to derive more of the

stimulus which your enthusiasm gives me in my work. Speaking not only

in my own name but[4] in behalf of my colleagues on the Board of

Governors and the Faculty of The Dropsie College for Hebrew and

Cognate Learning, I wish your Association and your Journal success in

all of your endeavors.

From Louis D. Brandeis

Chairman of the Provisional Executive Committee for General Zionist

Affairs

THE formation at Harvard University on October 25, 1906, of the first

Menorah Society is a landmark in the Jewish Renaissance. That

Renaissance, in which the Society is certain to be a significant

factor, is of no less importance to America than to its Jews.

America offers to man his greatest opportunity—liberty amidst peace

and large natural resources. But the noble purpose to which America is

dedicated cannot be attained unless this high opportunity is fully

utilized; and to this end each of the many peoples which she has

welcomed to her hospitable shores must contribute the best of which it

is capable. To America the contribution of the Jews can be peculiarly

large. America's fundamental law seeks to make real the brotherhood of

man. That brotherhood became the Jews' fundamental law more than

twenty-five hundred years ago. America's twentieth century demand is

for social justice. That has been the Jews' striving ages-long. Their

religion and their afflictions have prepared them for effective

democracy. Persecution made the Jews' law of brotherhood

self-enforcing. It taught them the seriousness of life; it broadened

their sympathies; it deepened the passion for righteousness; it

trained them in patient endurance, in persistence, in self-control,

and in self-sacrifice. Furthermore, the widespread study of Jewish law

developed the intellect, and made them less subject to preconceptions

and more open to reason.

America requires in her sons and daughters these qualities and

attainments, which are our natural heritage. Patriotism to America, as

well as loyalty to our past, imposes upon us the obligation of

claiming this heritage of the Jewish spirit and of carrying forward

noble ideals and traditions through lives and deeds worthy of our

ancestors. To this end each new generation should be trained in the

knowledge and appreciation of their own great past; and the

opportunity should be afforded for the further development of Jewish

character and culture.

The Menorah Societies and their Journal deserve most generous support

in their efforts to perform this noble task.

[5]

From Dr. Richard Gottheil

Professor of Rabbinical Literature and the Semitic Languages,

Columbia University

I HAVE been asked to say a word of greeting to the readers of the

Menorah Journal. I do so with pleasure; indeed with much satisfaction.

The Menorah students at our colleges and universities will now be

bound together by a new bond, one that will give them a more unified

direction and converge their efforts toward the goal which the Menorah

has set for itself.

I should like to think that it is not entirely fortuitous that this

added impulse is given to our work just at this time. We all feel that

the present is a moment when the very foundations of our ethical

life—both as individuals and as groups—have received a rude shock.

At such a time—more than ever—we need to understand and to bear in

mind the great teachings which Jewish sages have given to the world,

as their and our contribution to the moral foundations of society.

Such teachings were, in most cases, not decked out in the tawdry

trappings of a recondite and far-fetched philosophy, nor garnished

with the decorations of superlogical terminology, nor even put forth

with lusty rhetoric. They were simple and to the point, because they

were founded upon deep religious convictions.

One of these teachings occurs to me as I write these lines: "The moral

condition of the world depends upon three things—truth, justice and

peace." Have we outgrown such teaching? Have the astounding advances

made during the last one hundred years in the science of physical

living brought us any nearer to the true inwardness of moral living

than the ethical principles put forth by these early teachers? As our

hearts are rent by the sufferings of those who are caught in the

meshes of the terrible war now raging, and as our intellects are

befogged by the various excuses advanced in justification of carnage

and wholesale destruction, do not the simple words of the old Hebrew

sage appear to us as a beacon-light in the surrounding darkness?

"Truth, Justice, Peace!"

Many similar lessons are awaiting those who will show some little

willingness to learn and to know. They are a part of the patrimony

that is ours, and which for the most part we refuse to claim. A voice

is crying to us out of our own midst. We do not hear; for our ears are

sealed as with wax. The Menorah Societies, which now are to be found

in most of our institutions of higher learning, have set themselves

the task of bringing our Jewish students to a consciousness of their

own past, to a knowledge of their history as members of a great

historic people, and to a just appreciation of the teachings of their

religion. It is only the knowledge of what we have tried to be that

will make us realize fully what we are and will enable us to see what

our future may be. The Menorah Journal is intended to bring this

knowledge to our young men, to harden their Jewish resolve and to

point the way along which lies the consummation of our Jewish hopes.

It sends its greeting to every Jewish student, whether or not he be a

member of a Menorah Society. We of an older generation look to our

university and college men as the Jewish leaders of the future. Let

them gather[6] around the Menorah Journal in order to make it a true

expression of Jewish ideals, a powerful incentive to join the ranks of

those who are active in our cause. The word of the Prophet comes to me

again: "Be ye strong, therefore, and let not your hands be weak; for

your work shall be rewarded."

From Joseph Jacobs

Editor of The American Hebrew, New York

I GREET the appearance of the official organ of the Menorah Societies

something in the spirit of Ibsen's Master-Builder, who hears the

coming generation knocking at the door. I have long been of the

opinion that the future of American Israel lies with the academic Jews

of the American universities. The organ that represents them should

be, from this point of view, the voice of Israel's future in America.

If you can live up to that ideal, you have indeed a great future

before you.

From Dr. Kaufman Kohler

President of Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati

AS you wander through the ruins of the

Forum Romanum and are within

sight of the

Via Appia at the other end, your attention is riveted

by an exquisite white marble arch wonderfully preserved. It is the

Arch of Titus erected in memory of Rome's triumph over

Judæa Capta.

As you look closer at the trophies chiseled on this famous monument,

you find there standing out most conspicuously the seven-armed

candlestick carried by the Jewish captives, the

Menorah, regarded,

no doubt, by the proud victor as the most characteristic feature of

the destroyed Jewish temple. Yet how strange! It seems to be almost a

foreboding of the future dominion of the vanquished over the

vanquisher. Israel's state, with its temple, Israel's nationality was

trampled under foot by the Roman legions—Israel's religion remained

unconquered, the light of its truth remained undimmed; nay, it grew

brighter and stronger until the world was filled with its splendor.

Little did the Emperor Vespasian dream, when he granted Rabbi Johanan

ben Zakkai, the Jewish maker of learning, the privilege of building a

schoolhouse at Jamnia as a substitute for the hall of the judiciary in

the temple at Jerusalem, that this sanctuary of the Jewish law and

what it

[7] represents would by far eclipse all the power and greatness

of the Roman civilization. Yet this was symbolized by the Menorah.

Whether originally intended or not, it was the emblem of Israel's

mission of light. It indicated the task of the Jew, when scattered

over the wide globe, to be a light to the nations, the religious

luminary to the world. And if we be permitted to give a special

meaning to the seven arms of light of the Golden Candlestick, we might

find therein a suggestion of the lights of truth, justice and purity,

or holiness, on the one side, and the lights of law, literature, and

art, or wisdom, on the other, while the light in the center stands for

religion, from which all the other lights emanated and for which the

Jew throughout the centuries lived, suffered, and died, to preserve

intact as mankind's highest treasure to the very end of history.

These ideas I would offer as greeting to the editors and readers of

the Menorah Journal. The name "Menorah" was aptly chosen by the

founders of the pioneer Menorah Society with a view to the two-fold

task of the light-bearer, to enlighten a surrounding world, and to

foster self-respect in the hearts of the Jewish students by spreading

the light of Jewish knowledge among them. Now, if I understand

correctly the purpose of starting a Journal as the organ of the

Intercollegiate Menorah Association, it is to give to these endeavors

a more permanent and classical literary form, and thus successfully

defend the cause of Judaism. Wishing this enterprise all success and

Godspeed, I venture to express the hope that true to its name Menorah,

the Journal will become a real banner-bearer of light not only

dispelling clouds of doubt and of prejudice within and outside of our

camp, but also aiming to spread the truth of Judaism in all its

spiritual force and grandeur. Not nationalism, which in these days of

a cruel world-war with its barbarism puts our much-vaunted modern

civilization to everlasting shame and which has split the Jewish

people also into warring camps, but Judaism as a religion, which

notwithstanding the differences of its various wings as to form is in

its essentials and fundamentals one, should be the watchword, for it

is the light of the Torah that is both law and learning, religion and

culture, which is to unify and consolidate all the forces of American

Israel.

From Irving Lehman

Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York

I CONGRATULATE the members of the Intercollegiate Menorah Association

upon the fact that in their Journal they are obtaining a new

instrument to carry forward their work of bringing to the Jewish youth

knowledge of the old ideals and lessons of the Jewish past. During

these dreadful days, the Jewish students of almost every country

except America have been called from study, and preparation for a life

of usefulness, into pitiless war

[8] and useless destruction. The

oppressed in Russia, the student in Germany, and the free Englishman,

all have answered the call to arms of the country in which they live,

and each is fighting, firm in the belief that he is defending his

Fatherland against foreign aggression. The loyalty shown by our

brethren even in those countries where their treatment might well have

furnished at least an explanation for disloyalty, is a new

demonstration of the ancient spirit of devotion to their ideals which,

I believe, has always been the true spirit of the Jews. But the ideal

of national physical strength is not the ideal which we Jews had when

we were a nation and which we must strive to make the ideal of the

modern nations in which we live. Dark though these present days are,

yet humanity must progress into the light of a permanent peace, and

though the Jews are doing their full share of the fighting in this war

brought on by their rulers, we must do more than our share in bringing

to its fruition the ancient prophecy: "For the law shall go forth from

Zion and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. And He shall judge many

people and rebuke strong nations, and they shall beat their swords

into ploughshares and their spears into pruning-hooks; nation shall

not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war any

more."

The voice of this Journal may be only a weak, small voice, but if that

voice speaks in the spirit of the prophet and brings home to us the

worth of the prophetic ideals, it may well prove an important factor

in enabling Israel to fulfill its mission as a messenger of peace to

all the nations.

From Julian W. Mack

Judge of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals

MY hopes are high that the Menorah Journal may prove a valuable means

not only of linking together the Menorah Societies of the country but

also of bringing to the individual members a clearer conception of the

culture, ideals and traditions of the Jews, thereby increasing their

interest in all things Jewish.

This would inevitably tend to strengthen the religious faith of the

Jewish members and to awaken in all of the members a keener and a more

intelligent appreciation of the contribution which Jews and Judaism

have made to human progress.

[9]

From Dr. J. L. Magnes

Chairman of Executive Committee, Jewish Community (Kehillah) of New

York

I SEND hearty greetings to the members of the Intercollegiate Menorah

Association upon the publication of the Journal. If the Journal can be

put upon a sound business basis assuring its permanence, its

publication will mark an important event in the development of Judaism

in America. What we need above all things is sound thinking on Jewish

affairs. I have no doubt that proper action will result from sound

thinking. The Menorah Journal ought to become the medium for

publishing the best thought modern Jewry is capable of. The present

catastrophe overwhelming Europe has conferred upon the Jews in America

the leadership of Jewry. We can assume this historic obligation only

if our theories be clear cut and well thought out.

From Dr. Martin A. Meyer

Rabbi of Temple Emanu-El, San Francisco

IT is a pleasure to know that a journal is being launched in America

for the benefit of thinking Jews, which will stand between the

technical journal of the "Quarterly" type and outside of the purlieus

of our numerous "Weekly" gossip sheets.

Jewish journalism in America has done little, if anything, to justify

the numerous calls which it makes upon the people for support. On the

other hand, there is sad need for a journal representative of our best

thought, which will be readable and which will represent rather than

misrepresent us.

The field of Jewish culture and ideals surely has not been exhausted

by our European brethren. No matter what they may have contributed to

the exploitation of this field there surely remains ample ground for

the American Jew to express himself in the light of the old standards

of Jewish conduct and belief.

It goes without saying that your Journal will make its primary appeal

to the college man and woman. If successful, it will have saved for

Jewry its most valuable elements and enable us to build in the future

on a better and broader basis than the purely financial and commercial

leadership of the past.

From the far West we join hands with you in the far East and unite in

fervent hopes that the new Menorah Journal may grow from strength to

strength.

[10]

From Dr. David Philipson

Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati

SOME seventy years ago the celebrated Jewish scholar, Abraham Geiger,

charged the Jewish intelligenzia of his day with indifference

towards Judaism and Jewish interests. This accusation of Geiger's has

since been repeated frequently. But a rift is appearing in the cloud.

To-day as never before our intelligenzia as defined by university

training and education is identifying itself more and more with Jewish

life and aspiration in our country. And I feel that due credit should

be given the Menorah movement in our colleges for this change of

attitude of Jewish students and professors. This movement, still

young, has accomplished much in bringing together the young men and

women who form our intellectual elite into associations for the study

of Jewish history and the consideration of Jewish problems. It has

awakened an interest in Jewish matters in many who have been lukewarm

and indifferent. It has brought as lecturers to our colleges Jewish

men of light and leading from many communities, who have voiced their

messages and given food for thought to the future leaders now sitting

on university benches.

The call of the ages sounds to the intellectual nobility of our day

and generation. Learning has been extolled among Jews from earliest

times, and the wise man has been the accredited leader, so that it was

declared that "the wise man is greater than the prophet." I would have

the learned classes come again into their own. I would have our

university men in coming years the staunchest Jews in the community

through their intelligent interest in everything that makes for its

highest welfare.

To achieve this is the task of our university men. The possibility of

this achievement I see in such significant signs as the Menorah

movement, the institution of student congregations, and the launching

of this magazine by the Intercollegiate Menorah Association. What has

been called the "Jewish consciousness," a term which has done yeoman's

service during the past decade, is being aroused through these

agencies to an even greater degree. This aroused Jewish feeling will,

I am sure, be translated into active service more and more as the

years pass and the present generation of college men carve out their

careers in our communities throughout the country. This is the great

Jewish opportunity of the present generation; in this will they

reverse, such is my hope and my belief, that condition and that

attitude of the Jewish intelligenzia in the past (and still largely

in the present) which evoked the statement of Abraham Geiger. May this

new undertaking prosper so that the young generation whom this

magazine represents may be helped toward a realization of its ideals,

and become an inspiration to all Jewry throughout the length and

breadth of the land.

[11]

From Dr. Solomon Schechter

President of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

I WISH to send my hearty congratulations to the Intercollegiate

Menorah Association upon their undertaking the publication of the

Menorah Journal, which I have no doubt will prove greatly helpful in

promoting the knowledge of Judaism among the Jewish college youth. In

a liberal country like ours, with the eagerness of our people for

acquiring knowledge, there never was a lack of Jews in our Colleges

and Universities. But what the Menorah Association will accomplish

with the aid of the Journal is, I hope, to have Judaism also

represented in our seats of learning.

From Jacob H. Schiff

IT is with much satisfaction that I learn of the launching of the

Menorah Journal, to provide an opportunity for a more general spread

of the high ideals of the Menorah Societies among our college youth.

When I received some time ago a copy of the publication entitled "The

Menorah Movement," I noted with particular pleasure the progress the

Menorah Societies had already made. After an attentive perusal of the

contents of this publication, I felt as if a copy ought to be placed

in the hands of every Jewish college and university student, and I

myself distributed a number of copies for propaganda purposes. The

Menorah Societies are to be congratulated upon their new venture in

issuing the Journal, upon which I wish them every success. It is to be

hoped that the Menorah Journal will help the Jewish student to

understand what Judaism means and what as Jews we should strive for to

become useful and worthy citizens of this country. We shall have to

face increasing problems because of the deplorable war in Europe,

which so tragically affects our co-religionists there, and it will

require much devotion and understanding on our part to properly deal

with the conditions which will necessarily arise. The Menorah Journal

should freely discuss these conditions, so as to inspire its readers

with the desire to aid and the courage needed in the situation which

is facing us. Thus, by "spreading light," the Journal can greatly

assist the Menorah movement, and render efficient service in and

outside of the university. Let me wish Godspeed to your new

publication and its managers.

[12]

From Dr. Stephen S. Wise

Rabbi of the Free Synagogue, New York

I REJOICE to learn of the establishment of an organ by the Menorah

Association. The Menorah Journal will, I take it, serve the threefold

purpose of keeping the various groups of the Menorah throughout the

universities of the land in constant touch with one another, of

interpreting the ideals of the Menorah to widening circles of the

Jewish youth, and of confirming anew, from time to time, the loyalty

of the Menorah men to the Menorah ideal.

A truly great Jew said about fifteen years ago that a high

self-reverence had transformed arme Judenjungen into stolze junge

Juden. I believe that the Menorah movement in this land is in part

the cause and in other part the token of a transformation among young

American Jews to-day parallel to that cited by Theodor Herzl. It marks

a sea-change from the self pitying Jewish youth, immeasurably "sorry

for himself" because of his exclusion from certain dominantly

unfraternal groups, to the Jewish youth self-regarding, in the highest

sense of the term, self-knowing, self-revering. That the

self-respecting young Jew command the respect of the world without is

of minor importance by the side of the outstanding fact that he has

ceased to measure himself by the values which he imagined the

unfriendly elements of the world without had set upon him.

The Menorah movement is welcome as a proof of a new order in the life

of the young college Jew. He has come to see at last that it is comic,

in large part, to be shut out from the Greek letter fraternities of

the Hellenes and the Barbarians, but that it is tragic, in large part,

to shut himself out from the life of his own people. For it is from

his own people that he must draw his vision and spiritual sustenance

if he is to live a life of self-mastery rather than the life of a

contemptible parasite rooted nowhere and chameleonizing everywhere.

Time was when their fellow-Jews half excused the college men, who

drifted away from the life of Israel, as if the burden of the Jewish

bond were too much for the untried and unrobust shoulders of our

Jewish college men, as if their intellectual and moral squeamishness

led to inevitable revolt against association with their much-despised

and wholly misunderstood Jewish fellows. Now we see, and our younger

brothers of the Menorah fellowship have caught the vision, that no Jew

can be truly cultured who Jewishly uproots himself, that the man who

rejects the birthright of inheritance of the traditions of the

earliest and virilest of the cultured peoples of earth is

impoverishing his very being. The Jew who is a "little Jew" is less of

a man.

The Menorah lights the path for the fellowship of young Israel, finely

self-reverencing. Long be that rekindled light undimmed!

[13]

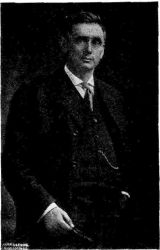

A Call to the Educated Jew

By Louis D. Brandeis

LOUIS D. BRANDEIS (born in Louisville, Ky., in 1856),

lawyer and publicist, is a distinguished leader in the voluntary

profession of "public servant." His extraordinary record of unselfish,

genuine achievement in behalf of the public interest—for shorter

hours of labor, savings bank insurance, protection against monopoly,

against increase in railroad rates, etc.,—gives peculiar aptness to

the appeal for community service made in this article, which Mr.

Brandeis has prepared from a recent Menorah address. From the

beginning Mr. Brandeis has taken a keen interest in the Menorah

movement as a promotive force for the ideals he has at heart.

LOUIS D. BRANDEIS (born in Louisville, Ky., in 1856),

lawyer and publicist, is a distinguished leader in the voluntary

profession of "public servant." His extraordinary record of unselfish,

genuine achievement in behalf of the public interest—for shorter

hours of labor, savings bank insurance, protection against monopoly,

against increase in railroad rates, etc.,—gives peculiar aptness to

the appeal for community service made in this article, which Mr.

Brandeis has prepared from a recent Menorah address. From the

beginning Mr. Brandeis has taken a keen interest in the Menorah

movement as a promotive force for the ideals he has at heart.

WHILE I was in Cleveland a few weeks ago, a young man who has won

distinction on the bench told me this incident from his early life. He

was born in a little village of Western Russia where the opportunities

for schooling were meagre. When he was thirteen his parents sent him

to the nearest city in search of an education. There—in

Bialystok—were good secondary schools and good high schools; but the

Russian law, which limits the percentage of Jewish pupils in any

school, barred his admission. The boy's parents lacked the means to

pay for private tuition. He had neither relative nor friend in the

city. But soon three men were found who volunteered to give him

instruction. None of them was a teacher by profession. One was a

newspaper man; another was a chemist; the third, I believe, was a

tradesman; all were educated men. And throughout five long years these

three men took from their leisure the time necessary to give a

stranger an education.

The three men of Bialystok realized that education was not a thing of

one's own to do with as one pleases—not a personal privilege to be

merely enjoyed by the possessor—but a precious treasure transmitted

upon a sacred trust to be held, used and enjoyed, and if possible

strengthened—then passed on to others upon the same trust. Yet the

treasure which these three men held and the boy received in trust was

much more than an education. It included that combination of qualities

which enabled and impelled these three men to give and the boy to seek

and to acquire an education. These qualities embrace: first,

intellectual capacity; second, an appreciation of the value of

education; third, indomitable will; fourth, capacity for hard

work. It was these qualities which[14] enabled the lad not only to

acquire but to so utilize an education that, coming to America,

ignorant of our language and of our institutions, he attained in

comparatively few years the important office he has so honorably

filled.

Now whence comes this combination of qualities of mind, body and

character? These are qualities with which every one is familiar,

singly and in combination; which you find in friends and relatives,

and which others doubtless discover in you. They are qualities

possessed by most Jews who have attained distinction or other success;

and in combination they may properly be called Jewish qualities. For

they have not come to us by accident; they were developed by three

thousand years of civilization, and nearly two thousand years of

persecution; developed through our religion and spiritual life;

through our traditions; and through the social and political

conditions under which our ancestors lived. They are, in short, the

product of Jewish life.

The Fruit of Three Thousand Years of Civilization

OUR intellectual capacity was developed by the almost continuous

training of the mind throughout twenty-five centuries. The Torah led

the "People of the Book" to intellectual pursuits at times when most

of the Aryan peoples were illiterate. And religion imposed the use of

the mind upon the Jews, indirectly as well as directly, and demanded

of the Jew not merely the love, but the understanding of God. This

necessarily involved a study of the Laws. And the conditions under

which the Jews were compelled to live during the last two thousand

years also promoted study in a people among whom there was already

considerable intellectual attainment. Throughout the centuries of

persecution practically the only life open to the Jew which could give

satisfaction was the intellectual and spiritual life. Other fields of

activity and of distinction which divert men from intellectual

pursuits were closed to the Jews. Thus they were protected by their

privations from the temptations of material things and worldly

ambitions. Driven by circumstances to intellectual pursuits, their

mental capacity gradually developed. And as men delight in that which

they do well, there was an ever widening appreciation of things

intellectual.

Is not the Jews' indomitable will—the power which enables them to

resist temptation and, fully utilizing their mental capacity, to

overcome obstacles—is not that quality also the result of the

conditions under which they lived so long? To live a Jew during the

centuries of persecution was to lead a constant struggle for

existence. That struggle was so severe that only the fittest could

survive. Survival was not possible except where there was strong

will—a will both to live and to live a Jew. The weaker ones passed

either out of Judaism or out of existence.

And finally, the Jewish capacity for hard work is also the product of[15]

Jewish life—a life characterized by temperate, moral living continued

throughout the ages, and protected by those marvellous sanitary

regulations which were enforced through the religious sanctions.

Remember, too, that amidst the hardship to which our ancestors were

exposed it was only those with endurance who survived.

So let us not imagine that what we call our achievements are wholly or

even largely our own. The phrase "self-made man" is most misleading.

We have power to mar; but we alone cannot make. The relatively large

success achieved by Jews wherever the door of opportunity is opened to

them is due, in the main, to this product of Jewish life—to this

treasure which we have acquired by inheritance—and which we are in

duty bound to transmit unimpaired, if not augmented, to coming

generations.

But our inheritance comprises far more than this combination of

qualities making for effectiveness. These are but means by which man

may earn a living or achieve other success. Our Jewish trust comprises

also that which makes the living worthy and success of value. It

brings us that body of moral and intellectual perceptions, the point

of view and the ideals, which are expressed in the term Jewish spirit;

and therein lies our richest inheritance.

The Kinship of Jewish and American Ideals

IS it not a striking fact that a people coming from Russia, the most

autocratic of countries, to America, the most democratic of countries,

comes here, not as to a strange land, but as to a home? The ability of

the Russian Jew to adjust himself to America's essentially democratic

conditions is not to be explained by Jewish adaptability. The

explanation lies mainly in the fact that the twentieth century ideals

of America have been the ideals of the Jew for more than twenty

centuries. We have inherited these ideals of democracy and of social

justice as we have the qualities of mind, body and character to which

I referred. We have inherited also that fundamental longing for truth

on which all science—and so largely the civilization of the twentieth

century—rests; although the servility incident to persistent

oppression has in some countries obscured its manifestation.

Among the Jews democracy was not an ideal merely. It was a practice—a

practice made possible by the existence among them of certain

conditions essential to successful democracy, namely:

First: An all-pervading sense of the duty in the citizen. Democratic

ideals cannot be attained through emphasis merely upon the rights of

man. Even a recognition that every right has a correlative duty will

not meet the needs of democracy. Duty must be accepted as the dominant

conception in life. Such were the conditions in the early days of the

colonies and states of New England, when American democracy reached

there its fullest[16] expression; for the Puritans were trained in

implicit obedience to stern duty by constant study of the Prophets.

Second: Relatively high intellectual attainments. Democratic ideals

cannot be attained by the mentally undeveloped. In a government where

everyone is part sovereign, everyone should be competent, if not to

govern, at least to understand the problems of government; and to this

end education is an essential. The early New Englanders appreciated

fully that education is an essential of potential equality. The

founding of their common school system was coincident with the

founding of the colonies; and even the establishment of institutions

for higher education did not lag far behind. Harvard College was

founded but six years after the first settlement of Boston.

Third: Submission to leadership as distinguished from authority.

Democratic ideals can be attained only where those who govern exercise

their power not by alleged divine right or inheritance, but by force

of character and intelligence. Such a condition implies the attainment

by citizens generally of relatively high moral and intellectual

standards; and such a condition actually existed among the Jews. These

men who were habitually denied rights, and whose province it has been

for centuries "to suffer and to think," learned not only to sympathize

with their fellows (which is the essence of democracy and social

justice), but also to accept voluntarily the leadership of those

highly endowed morally and intellectually.

Fourth: A developed community sense. The sense of duty to which I

have referred was particularly effective in promoting democratic

ideals among the Jews, because of their deep-seated community feeling.

To describe the Jew as an individualist is to state a most misleading

half-truth. He has to a rare degree merged his individuality and his

interests in the community of which he forms a part. This is evidenced

among other things by his attitude toward immortality. Nearly every

other people has reconciled this world of suffering with the idea of a

beneficent providence by conceiving of immortality for the individual.

The individual sufferer bore present ills by regarding this world as

merely the preparation for another, in which those living righteously

here would find individual reward hereafter. Of all the nations,

Israel "takes precedence in suffering"; but, despite our national

tragedy, the doctrine of individual immortality found relatively

slight lodgment among us. As Ahad Ha-'Am so beautifully said: "Judaism

did not turn heavenward and create in Heaven an eternal habitation of

souls. It found 'eternal life' on earth, by strengthening the social

feeling in the individual; by making him regard himself not as an

isolated being with an existence bounded by birth and death, but as

part of a larger whole, as a limb of the social body. This conception

shifts the center of gravity not from the flesh to the spirit, but

from the individual to the community; and concurrently with this

shifting, the problem of life becomes a problem not of individual, but

of social life. I live for the sake[17] of the perpetuation and happiness

of the community of which I am a member; I die to make room for new

individuals, who will mould the community afresh and not allow it to

stagnate and remain forever in one position. When the individual thus

values the community as his own life, and strives after its happiness

as though it were his individual well-being, he finds satisfaction,

and no longer feels so keenly the bitterness of his individual

existence, because he sees the end for which he lives and suffers." Is

not that the very essence of the truly triumphant twentieth-century

democracy?

The Two-fold Command of Noblesse Oblige

SUCH is our inheritance; such the estate which we hold in trust. And

what are the terms of that trust; what the obligations imposed? The

short answer is noblesse oblige; and its command is two-fold. It

imposes duties upon us in respect to our own conduct as individuals;

it imposes no less important duties upon us as part of the Jewish

community or race. Self-respect demands that each of us lead

individually a life worthy of our great inheritance and of the

glorious traditions of the race. But this is demanded also by respect

for the rights of others. The Jews have not only been ever known as a

"peculiar people"; they were and remain a distinctive and minority

people. Now it is one of the necessary incidents of a distinctive and

minority people that the act of any one is in some degree attributed

to the whole group. A single though inconspicuous instance of

dishonorable conduct on the part of a Jew in any trade or profession

has far-reaching evil effects extending to the many innocent members

of the race. Large as this country is, no Jew can behave badly without

injuring each of us in the end. Thus the Rosenthal and the white-slave

traffic cases, though local to New York, did incalculable harm to the

standing of the Jews throughout the country. The prejudice created may

be most unjust, but we may not disregard the fact that such is the

result. Since the act of each becomes thus the concern of all, we are

perforce our brothers' keepers. Each, as co-trustee for all, must

exact even from the lowliest the avoidance of things dishonorable; and

we may properly brand the guilty as traitor to the race.

But from the educated Jew far more should be exacted. In view of our

inheritance and our present opportunities, self-respect demands that

we live not only honorably but worthily; and worthily implies nobly.

The educated descendants of a people which in its infancy cast aside

the Golden Calf and put its faith in the invisible God cannot worthily

in its maturity worship worldly distinction and things material. "Two

men he honors and no third," says Carlyle—"the toil-worn craftsman

who conquers the earth and him who is seen toiling for the spiritually

indispensable."

And yet, though the Jew make his individual life the loftiest, that

alone will not fulfill the obligations of his trust. We are bound not

only to use[18] worthily our great inheritance, but to preserve and, if

possible, augment it; and then transmit it to coming generations. The

fruit of three thousand years of civilization and a hundred

generations of suffering may not be sacrificed by us. It will be

sacrificed if dissipated. Assimilation is national suicide. And

assimilation can be prevented only by preserving national

characteristics and life as other peoples, large and small, are

preserving and developing their national life. Shall we with our

inheritance do less than the Irish, the Servians, or the Bulgars? And

must we not, like them, have a land where the Jewish life may be

naturally led, the Jewish language spoken, and the Jewish spirit

prevail? Surely we must, and that land is our fathers' land: it is

Palestine.

A Land Where the Jewish Spirit May Prevail

THE undying longing for Zion is a fact of deepest significance—a

manifestation in the struggle for existence. Zionism is, of course,

not a movement to remove all the Jews of the world compulsorily to

Palestine. In the first place, there are in the world about 14,000,000

Jews, and Palestine would not accommodate more than one-fifth of that

number. In the second place, this is not a movement to compel anyone

to go to Palestine. It is essentially a movement to give to the Jew

more, not less, freedom—a movement to enable the Jews to exercise the

same right now exercised by practically every other people in the

world—to live at their option either in the land of their fathers or

in some other country; a right which members of small nations as well

as of large—which Irish, Greek, Bulgarian, Servian or Belgian, as

well as German or English—may now exercise.

Furthermore, Zionism is not a movement to wrest from the Turk the

sovereignty of Palestine. Zionism seeks merely to establish in

Palestine for such Jews as choose to go and remain there, and for

their descendants, a legally secured home, where they may live

together and lead a Jewish life; where they may expect ultimately to

constitute a majority of the population, and may look forward to what

we should call home rule.

The establishment of the legally secured Jewish home is no longer a

dream. For more than a generation brave pioneers have been building

the foundations of our new old home. It remains for us to build the

superstructure. The Ghetto walls are now falling, Jewish life cannot

be preserved and developed, assimilation cannot be averted, unless

there be reëstablished in the fatherland a center from which the

Jewish spirit may radiate and give to the Jews scattered throughout

the world that inspiration which springs from the memories of a great

past and the hope of a great future. To accomplish this it is not

necessary that the Jewish population of Palestine be large as compared

with the whole number of Jews in the world. Throughout centuries when

the Jewish influence was great, and it was working out its own, and in

large part the world's, destiny during the[19] Persian, the Greek, and

the Roman Empires, only a relatively small part of the Jews lived in

Palestine; and only a small part of the Jews returned from Babylon

when the Temple was rebuilt.

The glorious past can really live only if it becomes the mirror of a

glorious future; and to this end the Jewish home in Palestine is

essential. We Jews of prosperous America above all need its

inspiration. And the Menorah men should be its builders.

THERE are two things necessary in the Jewish life of

this country. The one is an heroic attempt to organize

the Jews of the country for Jewish things. That can be

done, I believe, primarily through the organization of

self-conscious Jewish communities throughout the

country. The other thing necessary is, that we have

vigorous Jewish thinking. We need a theory, a

substantial theory, for our Jewish life, just as much

as we need Jewish organization. We need to have our

college men think their problems through without fear,

courageously, by whatever name their theories may be

known, be these theories called Zionism or

anti-Zionism, Reform Judaism or Orthodox Judaism. We

need some vigorous Jewish thinking.—From a Menorah

Address by Dr. J. L. Magnes.

[20]

Menorah

By William Ellery Leonard

WILLIAM ELLERY LEONARD (born in New Jersey in 1876),

Assistant Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, is the

author of several volumes of verse and literary criticism which have

won high praise,—notably "Sonnets and Poems," "Byron and Byronism in

America," and "The Vaunt of Man."

WILLIAM ELLERY LEONARD (born in New Jersey in 1876),

Assistant Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin, is the

author of several volumes of verse and literary criticism which have

won high praise,—notably "Sonnets and Poems," "Byron and Byronism in

America," and "The Vaunt of Man."

| WE'VE read in legends of the books of old |

| How deft Bezalel, wisest in his trade, |

| At the command of veilèd Moses made |

| The seven-branched candlestick of beaten gold— |

| The base, the shaft, the cups, the knops, the flowers, |

| Like almond blossoms—and the lamps were seven. |

We know at least that on the templed rock |

| Of Zion hill, with earth's revolving hours |

| Under the changing centuries of heaven, |

| It stood upon the solemn altar block, |

| By every Gentile who had heard abhorred— |

| The holy light of Israel of the Lord; |

| Until that Titus and the legions came |

| And battered the walls with catapult and fire, |

| And bore the priests and candlestick away, |

| And, as memorial of fulfilled desire, |

| Bade carve upon the arch that bears his name |

| The stone procession ye may see today |

| Beyond the Forum on the Sacred Way, |

| Lifting the golden candlestick of fame. |

The city fell, the temple was a heap; |

| And little children, who had else grown strong |

| And in their manhood venged the Roman wrong, |

| Strewed step and chamber, in eternal sleep. |

| But the great vision of the sevenfold flames |

| Outlasted the cups wherein at first it sprung. |

| The Greeks might teach the arts, the Romans law; |

| The heathen hordes might shout for bread and games; |

| Still Israel, exalted in the realms of awe, |

| Guarded the Light in many an alien air, |

| Along the borders of the midland sea |

| [21]In hostile cities, spending praise and prayer |

| And pondering on the larger things to be— |

| Down through the ages when the Cross uprose |

| Among the northern Gentiles to oppose: |

| Then huddled in the ghettos, barred at night, |

| In lands of unknown trees and fiercer snows, |

| They watched forevermore the Light, the Light. |

The main seas opened to the west. The Nations |

| Covered new continents with generations |

| That had their work to do, their thought to say; |

| And Israel's hosts from bloody towns afar |

| In the dominions of the ermined Czar, |

| Seared with the iron, scarred with many a stroke, |

| Crowded the hollow ships but yesterday |

| And came to us who are tomorrow's folk. |

| And the pure Light, however some might doubt |

| Who mocked their dirt and rags, had not gone out. |

The holy Light of Israel hath unfurled |

| Its tongues of mystic flame around the world. |

| Empires and Kings and Parliaments have passed; |

| Rivers and mountain chains from age to age |

| Become new boundaries for man's politics. |

| The navies run new ensigns up the mast, |

| The temples try new creeds, new equipage; |

| The schools new sciences beyond the six. |

| And through the lands where many a song hath rung |

| The people speak no more their fathers' tongue. |

| Yet in the shifting energies of man |

| The Light of Israel remains her Light. |

| And gathered to a splendid caravan |

| From the four corners of the day and night, |

| The chosen people—so the prophets hold— |

| Shall yet return unto the homes of old |

| Under the hills of Judah. Be it so. |

| Only the stars and moon and sun can show |

| A permanence of light to hers akin. |

What is that Light? Who is there that shall tell |

| The purport of the tribe of Israel?— |

| In the wild welter of races on that earth |

| Which spins in space where thousand other spin— |

| The casual offspring of the Cosmic Mirth |

| [22]Perhaps—what is there any man can win, |

| Or any nation? Ultimates aside, |

| Men have their aims, and Israel her pride. |

| She stands among the rest, austere, aloof, |

| Still the peculiar people, armed in proof |

| Of Selfhood, whilst the others merge or die. |

| She stands among the rest and answers: "I, |

| Above ye all, must ever gauge success |

| By ideal types, and know the more and less |

| Of things as being in the end defined, |

| For this our human life by righteousness. |

| And if I base this in Eternal Mind— |

| Our fathers' God in victory or distress— |

| I cannot argue for my hardihood, |

| Save that the thought is in my flesh and blood, |

| And made me what I was in olden time, |

| And keeps me what I am today in every clime." |

[23]

The Jews in the War

By Joseph Jacobs

JOSEPH JACOBS (born in New South Wales in 1854), noted

author and editor, was one of England's well-known scholars and men of

letters when he was called to America to become managing editor of the

Jewish Encyclopedia. He has held the chair of English literature at

the Jewish Theological Seminary, and is now editor of the American

Hebrew. He is the author of many authoritative books, including "Jews

of Angevin England," "Studies in Jewish Statistics," "Jewish Ideals,"

and "Literary Studies."

JOSEPH JACOBS (born in New South Wales in 1854), noted

author and editor, was one of England's well-known scholars and men of

letters when he was called to America to become managing editor of the

Jewish Encyclopedia. He has held the chair of English literature at

the Jewish Theological Seminary, and is now editor of the American

Hebrew. He is the author of many authoritative books, including "Jews

of Angevin England," "Studies in Jewish Statistics," "Jewish Ideals,"

and "Literary Studies."

IT is of course difficult to conjecture what will be the ultimate

effect of such a world-cataclysm as the present European war on the

fate of the Jews of the world. The chief center of interest naturally

lies in the eastern field of the war which happens to rage within the

confines of Old Poland. This kingdom, founded by the Jagellons,

brought together Roman Catholic Poland and Greek Catholic Lithuania

and could not, therefore, apply in full rigor the mediaeval principle

that only those could belong to the State who belonged to the State

Church. Hence a certain amount of toleration of religious differences,

which led to Poland forming the chief asylum of the Jews evicted from

Western Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. As a

consequence here lies the most crowded seat of Jewish population in

the world. From it comes the vast majority of the third of a million

Jews in the prime of life who are fighting for their native countries

and often against their fellow-Jews. Probably three hundred thousand

Jewish soldiers are under arms in this district. Besides the

inevitable loss by death of many of these and the distress caused by

the removal of so many others for an indefinite period from

breadwinning for their families, there must be ineffable woe caused by

the fact that this district is the scene of strenuous conflicts, which

lead to the wholesale destruction of the Jewish homes in a literal

sense. When one reflects that one out of every six of the inhabitants

of Russian, Prussian, and Austrian Poland is a Jew, the extent of the

misery thus caused may be imagined. One meets friends whose

birth-place changes nationality from week to week, according as the

different armies take possession. The Jewish inhabitants of Suwalki,

for example, must be doubtful whether they are Germans or Russians,

according as Uhlan or Cossack holds control of their city. But

whichever wins, for the time being, the non-combatants suffer by the

demolition of their houses,

[24] the requisition of their property, and

above all by the dislocation of their trade. The mass of misery caused

by the present war in this way to the Jews of Russian, Prussian, and

Austrian Poland is incalculable.

Nor is this direct loss and misery compensated for by any hope of

improved conditions after the war is concluded. One may dismiss at

once the rumor that the Czar has promised his Jewish soldiers any

alleviation of their lot, on account of their loyalty and bravery.

Such rumors are always spread about when the Russian autocracy needs

Jewish blood or money. Besides, we all know the value of the plighted

word of the crowned head of the Russian Church; the emasculation of

the Duma is sufficient evidence of this. And even if the Czar carries

out his promise of giving autonomy to Poland, including any sections

of Prussian and Austrian territory which he may acquire by the present

war, the Jewish lot will not be ameliorated in the slightest. For,

unfortunately, Poles have of recent years turned round on their Jewish

fellow sufferers from Russian tyranny somewhat on the principle of the

boy at school who "passes on" the blow which he has received from a

bigger boy to one smaller yet.

The Probable Strengthening of Anti-Semitic Influences

BUT the chief evil which will result from the present war, whatever

its outcome, will be the increased influence of just those circles

from whom the anti-Semitic movement has emanated throughout Europe for

the past forty years. It is, in my opinion, absurd to think that

militarism will be killed or even scotched by the present war;

militarism cannot cast out militarism. Even if Germany is defeated, it

is impossible to imagine that she will rest content with her defeat,

and practically the only change in the situation will be that "La

Revanche" will be translated into "Die Rache"; and in Russia, the

defeat of Germany will simply increase the prestige and influence of

the grand-ducal circles from which the persecution of the Jews has

mainly emanated.

In the contrary case, if Germany gets the upper hand, the influence of

the Junkers in Germany, with their anti-Semitic tendencies, would be

raised to intolerable limits, while the Reaction in Russia, even if it

loses prestige, will yet be granted more power in order to carry out

the projected revenge.

Diminished Chances of Emigration

ANOTHER unfortunate result for Jews from the present war will be the

decreased stream of emigration from Russia and Galicia to this

country, so that the escape from the House of Bondage would be still

more limited. Many will be so impoverished by the war that they will

not be able to afford the minimum sum needed for migration. Death on

the

[25] battle-field or in the military hospitals will remove many

energetic young fellows who would otherwise have come to this country

and afterwards have brought their relatives with them. Conditions here

too, in the immediate future, are likely to be less attractive for the

immigrant from the economic point of view owing to the dislocation of

trade caused by the current conflict.

Altogether, as will have been seen from the above enumeration, I am

strongly of opinion that the Jews will suffer even more than most

peoples concerned in the present war. They have nothing to gain by it;

they are sure to lose by it.

SURELY a law, the essence of which is mercy and

justice to one's fellow men, is not a narrow rule of

life, to be discarded by us today on any plea that we

have outgrown it; surely a history of thousands of

years' devotion to spiritual ideals is not a history

to be forgotten. America is a land of divers races and

divers religions. Each race and each religion owes to

it the duty of bringing to its service all its

strength; it derives no added strength from a race

which has forgotten the lessons it has learnt in the

past, a race which deliberately discards the spiritual

strength which it has obtained by devotion to its

ideals.—From a Menorah Address by Justice Irving

Lehman.

[26]

Jewish Students in European Universities

By Harry Wolfson

HARRY WOLFSON (Harvard A. B. and A. M. 1912), a member

of the Harvard Menorah Society since 1908, was the Hebrew poet at the

annual Harvard Menorah dinners for four years, and won the Harvard

Menorah prize in 1911 for an essay on "Maimonides and Halevi: A Study

in Typical Jewish Attitudes Toward Greek Philosophy in the Middle

Ages." On graduating from Harvard he received honors in Semitics and

Philosophy, and was appointed to a Sheldon Traveling Fellowship. As

Sheldon Fellow he spent two years abroad, studying in the University

of Berlin and doing research work in the libraries of Munich, Paris,

the Vatican, Parma, the British Museum, Oxford and Cambridge. The

present article is based upon the impressions he gathered during this

period. He is now pursuing graduate studies in Semitics and Philosophy

at Harvard.

HARRY WOLFSON (Harvard A. B. and A. M. 1912), a member

of the Harvard Menorah Society since 1908, was the Hebrew poet at the

annual Harvard Menorah dinners for four years, and won the Harvard

Menorah prize in 1911 for an essay on "Maimonides and Halevi: A Study

in Typical Jewish Attitudes Toward Greek Philosophy in the Middle

Ages." On graduating from Harvard he received honors in Semitics and

Philosophy, and was appointed to a Sheldon Traveling Fellowship. As

Sheldon Fellow he spent two years abroad, studying in the University

of Berlin and doing research work in the libraries of Munich, Paris,

the Vatican, Parma, the British Museum, Oxford and Cambridge. The

present article is based upon the impressions he gathered during this

period. He is now pursuing graduate studies in Semitics and Philosophy

at Harvard.

THE Jewish student is no longer a déraciné. Deeply rooted to the

soil of Jewish reality, he is like the best of the academic youth of

other nations responsive to the needs of his own people. If in spots

he is still groping in the dark, he is no longer a lone, stray

wanderer, but is seeking his way out to light in the company of

kindred souls. A comprehensive and exhaustive study of native Jewish

student bodies in countries like England, Germany, Austria, France and

Italy, as well as of the Russian Jewish student colonies strewn all

over Western Europe, would bring out, in the most striking manner,

contrasting tendencies in modern Jewry. But that is far from the

direct purpose of this brief paper. As a student and traveler in

various European countries during the years 1912-1914 I had the

opportunity of observing Jewish student life and Jewish conditions in

general abroad, and it is merely a few random impressions of certain

aspects of these European conditions that I have here gathered

together for the readers of the Menorah Journal.

In England

JUDAISM in England, though of recent origin, is completely

domesticated. The Jewish gentleman is becoming as standardized as the

type of English gentleman. But more insular than the island itself,

Anglo-Jewry, as a whole, prefers to remain within its natural

boundaries, and is disinclined to become the bearer of the white Jew's

burden. Two of her great Jews, indeed, had embarked upon a scheme of

Jewish empire building. The attempts of both of them, however, ended

in a fizzle, for one was an unimaginative philanthropic squire, and

the other is an interpreter of the dreamers, himself too wide-awake to

become a master of dreams.

[27]

Yet within its own narrow limits, Anglo-Jewry is active enough to keep

in perfect condition. Over-exertion, however, is avoided. Cricket

Judaism is played according to the rules of the game, and the players

are quite comfortable in their flannels. The established synagogue of

Mulberry Street is as staid and sober as the Church of England, the

liberalism preached in Berkeley Street as gentle and unscandalizing as

the nonconformity of the City Temple, and the orthodoxy of the United

Synagogue as innocuously papish as the last phases of the Oxford

movement.

In England it is quite fashionable to admit Judaism into the parlor.

Parlor Judaism, to be sure, is not more vital a force nor more

creative than kitchen Judaism, but it seems to be more vital than the

Judaism restricted to the Temple. At least it is voluntary and

personal, and, what is more important, it is engaging. So engrossed in

the subject of his discussion was once my host at tea, that while

administering the sugar he asked me quite absent-mindedly: "Would you

have one or two lumps in your Judaism?" "Thank you, none at all," was

my reply. "But I am wont to take my Judaism somewhat stronger, if you

please."

Jewish Student Groups at Oxford and Cambridge

AS compared with ourselves, English Jews have a long tradition behind

them, in which they glory. That tradition does not at present seem to

stand any imminent danger of being interrupted. The younger generation

follow in the footprints of the older. Nowhere is there so narrow a

rift between Jewish fathers and sons as in England. Hence you do not

find there any prominent organization of the young. Last winter an

anonymous appeal for the organization of the Jewish students in

England ran for several weeks in the Jewish Chronicle, but it seems

to have resulted in nothing.

Independent local organizations of Jewish students, however, are to be

found in almost every university in England. In Oxford and Cambridge

they are organized in congregations, having Synagogues of their own,

in which the students assemble for prayer on every Friday night and

Saturday morning. In Cambridge they hold two services, an orthodox and

a liberal, both well attended. In Oxford they have recently published

a special prayer book of their own, suitable for the needs of all

kinds of students, it being a medley of orthodoxy and liberalism,

which if rather indiscriminate in its theology is, on the whole, made

up with good common sense. English liberal Judaism, it should be

observed, is markedly different from its corresponding cults in

Germany and in the United States. In Germany, reformed Judaism has its

nascence in free thought, and it aims to appeal to the intellectual.

With us liberalism is stimulated by our pragmatic evaluation of

religion, and is held out as a bait to the[28] indifferent. In England it

arises from the growing admiration on the part of a certain class of

Jews for what they consider the inwardness and the superior morality

of Christianity, and is concocted as a cure to those who are so

affected. As a result, English liberal Judaism is more truly religious

than the German, and more sincerely pious than the American. In a

sermon delivered before the Oxford congregation, a young layman of the

Liberal Synagogue of London apostrophized liberal Judaism as the

safeguard of the modern Jews from the attractiveness of the superior

teachings of Christ.

Social Service Work of Jewish Students

ENGLAND is the classic home of old-fashioned begging and of

old-fashioned giving. You are stopped for a penny everywhere and by

everybody, from the tramp who asks you to buy him a cup of tea, to the

hospital which solicits a contribution to its maintenance "for one

second." Pavement artists abound in Paris as much as in London, but in

Paris it is a Bohemian-looking denizen of the "Quartier" posing as a

pinched genius forced to sell his crayon masterpieces for a couple of

sous, whereas in London it is always a crippled ex-soldier trying to

arouse your pity in chalked words for a "poor man's talent." But

England is also the classic home of modern social service of every

description. The Salvation Army had its origin in London, where also

Toynbee Hall, the first University settlement of its kind, came into

existence. Likewise among the Jews, there are, on the one hand, the

firmly established old-fashioned charitable institutions to help the

"alien" brethren of the East End, and on the other hand, there are

also the equally well organized boys' clubs for the "uplifting" of the

"alien" little brethren of the same East End.

The Jewish University men in England take an active interest in both

these branches of philanthropy. It was a fortunate coincidence that

when I came to Oxford the Jewish students there had among them a

social worker of the latter type, who had come to make arrangements

for the reception of a squad of Whitechapel boys who were under his

tutelage. When I afterwards went to Cambridge I found there a delegate

of some charitable board of the London Jewish community, seeking to

enlist the aid of the Jewish students in his work.

What the Bulletin Boards Told at Berlin