| Thinking of Poland and her tortured Jews, |

| 'Twixt Goth and Cossack hounded, crucified |

| On either frontier, e'en the Pale denied, |

| Wand'ring with bloodied staff and broken shoes, |

| Scarred like their greatest son with stripe and bruise, |

| Though thrice a hundred thousand fight beside |

| Their Russian brethren and are glorified |

| By death for those who flout them and abuse,— |

I suddenly was touched to thankful tears. |

| Not that one wave had ebbed of all this woe, |

| Not that one heart had softened in "the spheres"[A] |

| One touch of bureau-malice to forego, |

| But that amid blind eyes, dumb mouths, deaf ears, |

| One voice in England[B] said these things were so. |

[A] Only permissible form of Russian reference to the Tsar and his Counsellors.

[B] The London Nation.

There is no limit to which the light cannot reach and there will be no limit, I hope, to the light which you will now spread. It will reach the remotest corner of the universities and schools of learning, nay, even more, it will bring everywhere a measure of knowledge and of truth, and above all it will illumine and warm. It will reach the eyes of those who have hitherto refused to see the beauty of their own past and the greatness of their own future. They may then learn to live in the present by the teaching of the past and by the hope of the future. Make both known.

In conclusion, I can only express the wish that you keep steadily and exclusively to Jewish questions, Jewish problems, Jewish learning. Make your readers know what they can find in Jewish literature and make the students of the various universities realize that in the libraries of Europe and America there are vast treasures accumulated which await the hand and the heart of the Jewish scholars. There are great and grave problems which await solution and the field is unlimited. Let them begin to till the ground of our own field, and turn the furrows and sow the seed, and the golden harvest is sure to repay them for their labor in the service of love and truth, and above all of devotion to Judaism.

The Jewish people stand on the brink of a new era in which they are to resume their true function of the spiritual teacher of mankind. And[74] American Jewry, it is a truism to say, has a vital and a leading part to play in moulding the destiny of the Jewish people. So we may adapt the old Rabbinic saying: "He who saves the soul of a single Jewish student is as though he saved the world." The Menorah Journal in holding up the light of the Jewish spirit to the young men and women of America is doing the work of humanity.

May I express the hope that the Menorah Societies will direct the gaze of their members to the land of promise and the land of the prophets, where the inspiration of Judaism has always come and whither the hopes of Jewry have always turned. Living as I do, in the reflection of Palestine as well as in the shadow of the Pyramids, I am very conscious of the need for a continued Passover from the ideas of the various Egypts that beset the Jewish people to the message that calls us, in spirit if not in body, to the land of our fathers. To-day in Palestine the light has begun to shine brightly again. Judaism has relit there its prophetic lamp, which in centuries of stress and darkness has never been permitted to fade away altogether. In our own time the Menorah has been re-established in the Temple of the land by a new band of Maccabees. But a single branch, so to say, of the seven branches as yet shows its clear light. But if the Jewish youth wills it, the whole Menorah may be lighted and shine full and clear to the world with fresh lustre. In our day there may be a new Hanukka, a rededication of the Hebraic light—if only we will it.

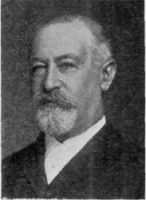

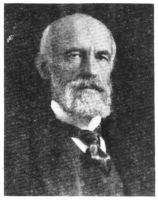

JACOB HENRY SCHIFF (born in Frankfort-on-the-Main,

Germany, in 1847, came to America in 1865), one of the world's leading

bankers (senior member of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., New York), and a prince of

philanthropists, noted for his personal devotion and munificent gifts

to many causes for human betterment. He was among the first to

encourage and befriend the Menorah movement, founding in 1907 the

annual Menorah Society Prize at Harvard. The present article forms the

approved substance of an interview granted by Mr. Schiff to the

Editors of The Menorah Journal on March 4, 1915. Mr. Schiff's

statement regarding the need for a separate Jewish Relief Fund is

given special significance by the fact that he is Treasurer of the

American Red Cross.

JACOB HENRY SCHIFF (born in Frankfort-on-the-Main,

Germany, in 1847, came to America in 1865), one of the world's leading

bankers (senior member of Kuhn, Loeb & Co., New York), and a prince of

philanthropists, noted for his personal devotion and munificent gifts

to many causes for human betterment. He was among the first to

encourage and befriend the Menorah movement, founding in 1907 the

annual Menorah Society Prize at Harvard. The present article forms the

approved substance of an interview granted by Mr. Schiff to the

Editors of The Menorah Journal on March 4, 1915. Mr. Schiff's

statement regarding the need for a separate Jewish Relief Fund is

given special significance by the fact that he is Treasurer of the

American Red Cross.

According to the latest reports, the conditions are not being improved in any way. And the relief so far has been entirely inadequate. It has never been adequate. We need millions for the immediate relief of our brethren, and so far only about half a million has been forthcoming from American Jews. This in spite of the fact that all parties and factions in Jewry are acting together in the work of relief, except only one organization, the B'nai B'rith, and for this there is some reason, because the B'nai B'rith have their own lodges abroad and they want evidently to apply their relief to their own members first.

Beyond the immediate measures for relief we can for the present do nothing. We must act from day to day. As the war goes on we must simply keep on trying to relieve the distress. As to what is in store after the war, I am unable to form a picture, at least so far as Russia is concerned. The hope is expressed that when peace is restored Russia will do better than heretofore for her large Jewish population. But we have been disappointed so often by Russia's promises that we should believe this only when actually done and not before. I have little confidence at all in the assertion that Russia will mend her way in the future.

The situation is different in Poland and Roumania, where the people themselves are anti-Semitic. It may appear strange at first that there should be such a difference between the Polish people and the Russian people in their attitude towards the Jews in their midst. But it may be easily explained. People who are oppressed generally become narrow by the oppression. The Poles and the Roumanians have had long to suffer from oppression to a great extent, the Poles from Russia and the Roumanians for many years from Turkey, from whose yoke they were freed only a few decades ago. It is generally a fact that when the servant becomes a master he makes the most intolerant master. Even if a Polish autonomous kingdom should be created, it could not be much worse for the Jewish population than it is now. But the Russian people have been happy. They have gotten used to their despotic government and do not feel it in particular, and they have little prejudice against their still greater oppressed Jewish neighbors.[77]

The great numbers of Jews who have gone into the war and are fighting heroically will, I have no doubt, make a convincing demonstration of Jewish patriotism in every country, and that should make for an improvement of Jewish conditions all over, except possibly in Russia.

In Germany the Jews do not suffer. They have a high standing and occupy many high positions. There has, it is true, always been a certain anti-Semitic tendency in Germany. But I think this war will crush out most of that, in fact all class differences. I am quite convinced that anti-Semitism in Germany is a thing of the past.

I do not think there is anything to do now for the Jews and for Jewish bodies in America except to work harmoniously together in the raising of relief funds. Of course, we must always be on the alert and ready to take a definite position whenever the proper time arrives. But not now. When peace negotiations begin to be talked about, I think it will be well for such bodies as the American Jewish Committee, possibly the B'nai B'rith and other organizations, to take united action. What action they should take it is hard to say. It is a very difficult question to decide at[78] this moment whether or not it would be advisable to have special Jewish representatives present at the peace negotiations to look after the specific Jewish interests. Whatever influence should be brought to bear at the proper time should originate with the American Jewish Committee, which is the most suitable unifying Jewish agent in America to-day.

HORACE MEYER KALLEN (born in Silesia, Germany, in

1882, came to America in 1887), studied at Harvard (A. B., Ph.D.),

Princeton, Oxford, and Paris. He has been assistant and lecturer in

philosophy at Harvard, instructor in logic at Clark University, and

since 1911 of the faculty of philosophy at the University of

Wisconsin. At the request of the late William James, he edited his

unfinished book on "Some Problems of Modern Philosophy." Besides

contributing to philosophical and general periodicals, Dr. Kallen is

the author of a recently published book on "William James and Henri

Bergson." Dr. Kallen was one of the founders of the Harvard Menorah

Society, and has rendered signal service, both by tongue and pen, to

the Menorah movement.

HORACE MEYER KALLEN (born in Silesia, Germany, in

1882, came to America in 1887), studied at Harvard (A. B., Ph.D.),

Princeton, Oxford, and Paris. He has been assistant and lecturer in

philosophy at Harvard, instructor in logic at Clark University, and

since 1911 of the faculty of philosophy at the University of

Wisconsin. At the request of the late William James, he edited his

unfinished book on "Some Problems of Modern Philosophy." Besides

contributing to philosophical and general periodicals, Dr. Kallen is

the author of a recently published book on "William James and Henri

Bergson." Dr. Kallen was one of the founders of the Harvard Menorah

Society, and has rendered signal service, both by tongue and pen, to

the Menorah movement.Why, in an officially neutral country, has this come to pass? When we look closely to the ground and principle of the division of sentiment in our population, we discover this significant fact: the division is not truly determined by the merits of the European issue; it is determined by the lines of our population's European origin and ancestral allegiance. The Americans of German and Austrian and Magyar ancestry are pro-German; those of French or British or Russian ancestry favor the Allies. Only the Jews seem to be an exception to this rule. Being mainly from Russia, their favor should go to the Russians, but their newspapers, almost without exception, favor the Germans. The case of the Jews, however, is an exception that proves the rule. Although the majority of them came from Russia, they have had no part in the Russian polity; they have been oppressed, persecuted, terrorized, as their brethren still are in Russian territory. As[80] Americans, what portion and what hope have they in Russia that they should desire Russian victory? None. But they are not for this reason in favor of Germany. The headlines of their newspapers do not celebrate German victories, but Russian defeats. The Ghetto's partiality to Germany is a consequence of its loyalty to Jewry. Kinship of blood and race, ancestral allegiance, determine with the Jewish masses in America also, what side they take in this war. Although they have no political background in Europe, and their civil allegiance is absolutely American, they too are hyphenated in sentiment—Jewish-Americans.

Such is the fact. Its significance lies in what it reveals, and what it reveals is a force much deeper and more radical, distinctly more primitive and original, than anything else in the structure of society. It hyphenates English and Germans and Austrians and Russians and Turks no less than it hyphenates Americans, and, in the failure of the external socio-political organization of Europe to give it free play, it is the chief, almost the only, cause of the present unendurable European tragedy. Its name is nationality.

The Swiss Republic, for example, is a nation composed of three nationalities, two of which belong to powers at war with each other. These are the French and the German; the third is the Italian. Yet the nationhood of Switzerland is the most integral and unified in Europe to-day, because Switzerland is as complete and thorough a democracy as exists in the civilized world, and the efficacious safeguard of nationhood is democracy not only of individuals but of nationalities. The German, French and Italian citizens of the Swiss Republic are to-day under arms to defend the neutrality of their nation from possible violation by German, French or Italian belligerents, and in defending their nation, they are defending also the autonomy of each other's nationality. In Switzerland, nationhood, being democratic, is the safeguard and insurance of nationality.

Contrast Swiss nationhood with Austro-Hungarian nationhood. Austria-Hungary is the immediate and direct occasion of the great war by reason of the fact that, although she is a mosaic of nationalities like[81] Switzerland, her government, instead of being a democracy, has in the long run been directed toward the control and exploitation of many nationalities by one or two. Hungary contains a population of seven million Magyars among twelve million Slavs; yet the Hungarians, having the economic and political upper hand, have sought to Magyarize by force and trickery this almost doubly greater and culturally equal population. They have tried to compel Magyar forms and standards in language, in literature, in history, the arts, the sciences, religion, law, in every intimate or remote concern of the daily life and national genius of their Slavic subjects. The result has been the steady disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian mosaic, the increasing use of force to hold it together, the corresponding increase of restlessness among the subject-peoples, plot and counterplot, the assassination of the Archduke, and the attack on Serbia, which precipitated the war. In this war Austria has come off worst of all the combatants, and for the same reason: the attempt to maintain the unity of a nation of nationalities by the force of one of them instead of by the democratic coöperation of all. In Austria-Hungary, nationality, having been exploited and suppressed, has been the enemy and destroyer of nationhood.

For the democracy of America had its first articulate voicing in the Pilgrim Fathers and the Puritans of New England. These men and women, devoted to the literature of the Old Testament, and upheld by the ancestral memories of the Jews, were moved to undertake their great American adventure by the ideal of nationality. It was not because of an overwhelming oppression of body and soul that the Pilgrims adventured to America. It was not "freedom to worship God" that they sought. They had that in Holland. They sought freedom to be themselves, to realize their national genius in their own individual way. Their English manners, English speech, English history, and English loyalty were, in fact, more important to them than their Hebrew Bible. They used that as the spiritual pabulum which nourished their English corporate life. Their Calvinism was a reinterpretation of its prophetic nationalism expressed in the doctrine of the "chosen people"; their political institutions were a modification of the ideal political order it was supposed to reveal. As Cotton Mather narrates,[82] his grandfather, John Cotton, found, on his arrival in New England, that the population was much exercised over the framing of a "civil constitution." They turned to him for help, begging "that he would, from the laws wherewith God governed his ancient people, form an abstract of such as were of a moral and lasting equity." So "he propounded unto them an endeavor after a theocracy, as near as might be to that which was the glory of Israel." Out of this beginning the democratic mood of America surges; in such conceptions the ideals which express the mood have their origins. These ideals are the conservation of nationality, and the equality of men before the inconceivable supremacy of their God. Hebraism and English nationality—these are the spiritual background of the American commonwealth.

Political freedom in America has tended to generate self-expression of each national group, and our country is to-day, broadly speaking, a great coöperative commonwealth of nationalities, British, French, German, Slavic, Jewish, each freely developing, in so far as it is self-conscious, its national genius, its language, literature and art in its own characteristic way as its best contribution to the civilization of America as a whole,[C] realizing in this way the ideal of the democracy of nationalities, of international comity and coöperation which our prophets were the first to formulate.

American nationhood, thus, is in the way of becoming what Swiss nationhood fully is, the liberator and protector of nationality; its democracy is its strength, and its democracy is "hyphenation." "Hyphenation" may, it is true, become perverse. As an expression of the coöperation of nationality with nationality in the life of the State, it is inevitable and good; as an attempt to subordinate all nationalities to one, to use all for the advantage of one, it is partial, undemocratic, disloyal. Our nation is a democracy of nationalities having for its aim the equal growth and free development of all. It can take no sides. To require it to take sides, German or Anglo-Saxon, Slavic or Jewish, is to be untrue to its spirit and to pervert its ideal.

The movement in modern history which we call progressive has been a movement toward democracy in both the internal affairs and external relationships of nations. Men did not realize its entire significance until the nineteenth[83] century; only then did it come to full consciousness in fact and idea, urged equally in Greece, in Germany, in Ireland, in Italy. Its great voice is the Italian thinker and patriot, Mazzini. In a marvelous essay entitled "Europe, Its Condition and Its Prospects," he wrote, at a time when the hope of social and international democracy seemed extinguished: "They struggled, they still struggle, for country and liberty; for a word inscribed upon a banner, proclaiming to the world that they also live, think, love and labor for the benefit of all. They speak the same language, they bear about them the impress of consanguinity, they kneel beside the same tombs, they glory in the same tradition; and they demand to associate freely, without obstacles, without foreign domination, in order to elaborate and express their idea, to contribute their stone also to the great pyramid of history. It is something moral which they are seeking; and this moral something is in fact, politically speaking, the most important question in the present state of things. It is the organization of the European task. In principle, nationality ought to be to humanity that which division of labor is in a workshop—the recognized symbol of association; the assertion of the individuality of a human group called by its geographical position, its traditions and its language, to fulfill a special function in the European work of civilization."

Modern Europe saw the overthrow of the Holy Roman Empire, of the imperial aspirations of Louis XIV, and of Napoleon before it realized the natural fact and moral principle which underlay these overthrows, and which finally so successfully asserted themselves as to unify Italy and cast off the Austrian dominion, to liberate Greece, Bulgaria, Roumania and the other Balkan States from the Turk, to unify and create contemporary Germany. The last quarter of the nineteenth century saw the renaissance, often in the face of overwhelming suppression, of the language and cultures of Czechs, Bohemians, Poles, Irish and Jews. It saw the rise of nationalism in the Oriental dependencies of Great Britain. It saw the beginning of an acknowledgment of the full rights of nationalities by both Austria and Great Britain, the grant of local autonomy to the various nationalities in the Austrian Empire, of progressive home rule to India and South Africa and Ireland. The twentieth century seemed to be moving peacefully toward the fulness of democracy—when came the war.

This is the issue between the warring powers and each claims that it is defending itself against the aggression of its opponents. Each claims to be fighting for democracy. In the face of these claims, history has the deciding voice. Now, historically, England, more than any other power, has stood for the democratic and coöperative idea. Her colonies have autonomy, her more backward dependencies are encouraged toward autonomy. Since the Boer war, when imperialism passed away, she has moved toward the position of Switzerland. Even Ireland has obtained home rule. "We are a great world-wide, peace-loving partnership," said Mr. Asquith,[D] has reiterated again and again the principle for which all the Allies are fighting: believing that "the preservation of local and national ties, of the genius of a people which has a history of its own, is not only not hostile to or inconsistent with, but on the contrary, fosters and strengthens and stimulates the spirit of a common purpose, of a corporate brotherhood," the Allies seek to defend public right, to find and to keep "room for the independent existence and free development of the smaller nationalities, each with a corporate consciousness of its own . . . and, perhaps, by a slow and gradual process, the substitution for force, for the clash of competing ambitions, for groupings and alliances and a precarious equipoise, of a real European partnership, based on equal right and enforced by a common will."[E]

It is hard to believe that Russia can be fighting for such an end. Fear of Russian barbarism is what brought Germany into the lists, the Germans declare, to defend western ideals and western democracy. Yet Russian government is Prussian in its organization, and it is on the side of the ideal of western democracy that she is explicitly aligned. The contradiction is striking, and it is still more striking when we recall that in her armies are over a quarter of a million of Jews, and that in the other armies there are half as many more. For the Jews the war is more than civil; it is[85] fratricide. On the face of it they have no inevitable personal or political stake in the war's fortune. England has acknowledged their "corporate consciousness" and given them maximal opportunity for "free self-development"; so has France. Russia has oppressed and horribly exploited them; Germany, though infinitely better than Russia, has set them conditions in which "free development" is synonymous with complete Germanization. Austria and Turkey have dealt with them somewhat after the manner of England and France. The contradiction of the Jewish position outdistances that of the Russian. But both contradictions are resolved in the fact that the ideal in question concerns not Russia alone, nor England alone, nor the Jews alone, but the whole of Europe, the whole world. What is at stake is not something local, personal, political, but a universal principle, the goal toward which mankind has been so slowly and deviously crawling from the beginnings of modern history—the principle of democracy in nationality and nationality in democracy.

It is for this that our brethren in the armies are fighting; it is for this that they are undergoing crucifixion in the Pale, for this that our people have suffered and died from the beginnings of our history. Our whole recorded biography is the narrative of a struggle for social justice against the exploitation of class by class within our polity, for nationality against imperialism without. Our statesmen and leaders were the first to formulate the ideal of the coöperative harmony of nationality, and the ideal of international peace.[F] Mr. Asquith is echoing our prophets, and our embattled brethren are engaged in the defence of a principle which is the constituent of the genius of their own nationality.

The indispensable condition for such a realization is autonomous nationality; not nationhood, necessarily, but autonomy. This, more than civil rights among other nationalities, is our stake in this great war. In the last analysis, the Hebraic culture and ideals which our Menorah Societies study, can be advanced, can be a living force in civilization, only as a national force. Our duty to America, inspired by the Hebraic tradition,—our service to the world, in whatever occupation,—both these are conditioned, in so far as we are Jews, upon the conservation of Jewish nationality. That is the potent reality in each of us, our selfhood, and service is the giving of the living self. Let us so serve mankind; as Jews, aware of our great heritage, through it and in it strong to live and labor for mankind's good.

[C] For a fuller treatment of this point compare in the New York Nation for February 18 and 25, 1915, the author's articles on "Democracy Versus the Melting Pot."

[D] Cardiff Speech, 2d October, 1914.

[E] Dublin Speech, 25th September, 1914.

[F] Cf. Isaiah, II, 2-4; XIX, 23-25; XI, 6-9; LXV, 17-25, etc.

G. STANLEY HALL (born in Ashfield, Mass., in 1846),

President of Clark University, is a leading authority on education and

psychology, and author of a number of important books, notably

"Adolescence" (2 vols. 1904). The present address, delivered at a

recent dinner of the Clark Menorah Society, has been revised by Dr.

Hall for publication in The Menorah Journal.

G. STANLEY HALL (born in Ashfield, Mass., in 1846),

President of Clark University, is a leading authority on education and

psychology, and author of a number of important books, notably

"Adolescence" (2 vols. 1904). The present address, delivered at a

recent dinner of the Clark Menorah Society, has been revised by Dr.

Hall for publication in The Menorah Journal.Again, I am always embarrassed in talking to members of your race because I feel a little as Napoleon did when he told his soldiers in Egypt that forty generations looked down on them from the top of the Pyramids. You know your ancestry in general back for thousands of years, and I am rarely fortunate in being able to go back as much as nine or ten generations to the Puritans of the "Mayflower," but there I stop and everything before that is a blank. David Starr Jordan tells us in his book that there is perhaps no man alive who has not kings or queens in his ancestry, but adds that we all have had murderers among our predecessors, too.

The old New England Puritan taught sternly. He was a patriarchal head of his family. In my boyhood, Saturday evening or perhaps better Thanksgiving Day, when their descendants all gathered together as long as either of the grandparents lived, we had an illustration of something very like Heine's touching picture of an old Jewish peddler who worked hard through the week, but on Friday night put on his long black coat and his three-cornered hat, lit the seven candles at the table, and told his children and grandchildren how Jehovah had led His people through the wilderness, and how the Egyptians and all the other naughty people who persecuted them were long since dead, while the chosen race survived. And so happy in his race was this poor peddler and so proud of his pedigree that, as Heine says, had the great Rothschild entered at that moment and asked him what favor he could do, he would reply simply: "Stand out of my light, that I may finish telling the law to my children."

As I read the Old Testament, the substance of the covenant with Abraham was that if he kept Jehovah's law, his seed would be multiplied like the stars of Heaven. This placed society and life in that early day squarely on a eugenic basis, for it makes the number and success of good children the supreme test of every human institution, activity, and every[89] kind of culture. This I take it is one of the chief characteristics of your race, and I hope it may long be so.

I am going to avail myself of this opportunity to say a few words about a topic that has for centuries been a point of the very greatest difference and tension between your people and mine, namely, the character and work of Jesus. Please do not be shocked till you hear what I have to say. Such of us psychologists as have recently been interested in the psychological aspect of Jesus' life and work understand, as had never been understood before, how purely Jewish he was. Scholars have lately given to his figure a radically new interpretation.

The Jews are never beaten; if checked in their aspirations they, like the prophets in the days of captivity, strike out in higher and nobler ways. Thus you ought to be proud of Jesus for, as he is now being understood, he was an extremely representative man of your race. The real enemies of the Jews are now claiming that no such man ever lived, which is the view of Drews and his school, some holding that he was a deliberate invention of the early decades of the first century, and others, like Jensen, that he was a revived Babylonian myth. But these new views show that Jesus was not an Aryan, as a few of the pan-Germanists have claimed, but a typical Semite. It does look now, in view of the teachings of such men as Gobineau and various of his successors, that the Aryans are the highest and best people in the world and that the Germans are the very best of all the Aryans, that it is Germany that has come to consider itself the chosen people, the elite, superior race. But certainly Germany is not very[90] Christian. It was only converted in the thirteenth century, and Luther soon threw off the fully developed Christianity of Rome. Since then we have had the Tübingen School, that resolved everything into myth, and the very many other negative points of view expressed in Nietzsche's supremest condemnation of Jesus as a wretched degenerate, while Wagner's deliberate slogan was, "Das Deutschtum muss das Christentum siegen."

I cannot but wonder, therefore, whether, in view of these new conceptions, Jew and Gentile are not going to meet in this country and even agree about Jesus. It is difficult at least to see which of us would change most if there were this rapprochement. We must neither of us abandon our birthright. We must be the very best Puritan Anglo-Saxons we possibly can, and you must be the best Jews possible, for out of these component elements American citizenship is made up. This country stands for the dropping of old prejudices, such as those that are inflaming Europe now with war. If we can satisfy each other's ideals and meet half way the thing is done, and the melting pot which America stands for has got in its work. I want the Menorah Society to feel that it is in the van of this movement.

MOSES HYAMSON (born in Suwalki, Russia, in 1863, came

to England in childhood). Rabbi and jurist; educated at Jews' College

and University College of London; for thirteen years Senior Dayan of

the London Beth-Din (Jewish Court of Arbitration), in which capacity,

because of his erudition in both the Jewish and the common law, he

rendered notable service to the British community. In 1913 he accepted

a call from the Congregation Orach Chayim of New York. Besides being a

contributor to the Jewish Quarterly Review and other learned

publications, Dr. Hyamson has published "The Oral Law and Other

Sermons" (1901), and an annotated edition of the medieval "Collatio

Romanorum et Mosaicarum Legum" (1912).

MOSES HYAMSON (born in Suwalki, Russia, in 1863, came

to England in childhood). Rabbi and jurist; educated at Jews' College

and University College of London; for thirteen years Senior Dayan of

the London Beth-Din (Jewish Court of Arbitration), in which capacity,

because of his erudition in both the Jewish and the common law, he

rendered notable service to the British community. In 1913 he accepted

a call from the Congregation Orach Chayim of New York. Besides being a

contributor to the Jewish Quarterly Review and other learned

publications, Dr. Hyamson has published "The Oral Law and Other

Sermons" (1901), and an annotated edition of the medieval "Collatio

Romanorum et Mosaicarum Legum" (1912).So runs the Talmudic tale. The incident happened in Palestine in the century before the common era. The boy Hillel had come from his obscure home in Babylon, bent upon study at the most famous school in Palestine, whose teachers, Shemaya and Abtalion, were heads of the Synhedrion, the Supreme Court of Jurisdiction. Poor and proud, Hillel supported himself by manual labor while he was securing his education. Like Abraham Lincoln, he was a woodchopper. One half of the small amount he earned daily served for his meals, and the other half he paid to the porter at the college for his admission in the evening. On this short Friday in mid-winter he had been able to earn nothing, and in his keen anxiety not to miss the lecture and discussion, he clambered to the roof of the college hall, braving snow and cold for the words of the living God as expounded by his teachers.

Within a few short years Hillel himself had succeeded his teachers as the head of this famous school, and also as President of the Synhedrion. Hillel's career is a shining example of the democratic principle which has always prevailed in Jewish life, of the opportunity open to all men of talents, however humble their origin, to achieve position in the republic[92] of Jewish learning. And learning combined with noble character, as in the case of the great Hillel, carried authority in Jewish life. It is true that Hillel was not without letters patent of nobility; though he came from poverty and obscurity and from an alien land, he was, according to tradition, of the blood of David. It is not, however, to this accident of birth, known only later, that Hillel owed his quick rise and supreme eminence in Jewish life, but to his distinguished attainments, to his profound learning not only in the Jewish Law but in many secular fields of knowledge, to his bold and original mind combined with a pious devotion to tradition, to his indomitable energy and industry, his nobility of character, his sympathy with the people and his understanding of their needs.

And in the interpretation of that "commentary" which, together with the Torah itself, enshrined the spirit of Judaism and made it a throbbing reality in the life of the nation, Hillel brought out the humanity of every regulation, the true intent behind it, whenever literal enforcement would have worked hardship or might have defeated its true intent because of the changed circumstances since its enactment. While keeping faithfully within the spirit of Jewish tradition, Hillel struck out into innovations, new precedents and legal institutions, which testified at once to the remarkable insight and boldness of his mind as a jurist and to his tact and sympathy as a leader of the people. Some of his innovations anticipate in a striking way the developments under similar circumstances of the common law of England and the United States many centuries later.

Other decisions of Hillel equally significant could be cited. To lawyers especially, the study of them is fascinating; they are full of startling relevancy in the present time of unrest and agitation for legal reform in this country. And not without reason. What we are keen for now is a greater measure of social justice in a democratic community. A study of Hillel's jurisprudence—both the theory and the decisions affecting the workaday life of the people—will give one an appreciation not only of the beautiful spirituality of the master, his erudition and his imagination, but the characteristic coalition of letter and spirit, the emphatic sense of social justice, which has prevailed in the whole system of Jewish law.

Hillel's character is illustrated by a number of pregnant sayings of his that have been recorded in the Talmud. "Do not separate yourself from the community," was one of his characteristic sayings which genuinely expressed his public spirit. His sense of individual and social responsibility is summed up in his three famous questions: "If I am not for myself, who will be for me? But if I am for myself alone, what am I? And if not now, when?" His peace-loving nature and humanity found voice in his counsel: "Be of the disciples of Aaron, loving peace, pursuing peace, loving God's creatures and bringing them near to the knowledge of the Law." His disinterestedness, his liberal pursuit of the Law, that is, of knowledge, made him confidently say: "He who aggrandizes his name, his name shall perish. He who does not add to his store of learning and good deeds will suffer diminution. He who does not teach deserves death. He who uses the crown of the Law for selfish needs and personal advancement will be destroyed." Who had a better right than Hillel, graduate of poverty, to warn his contemporaries: "Do not say I shall learn when I will have leisure; perhaps you never will have leisure." And in every case, even when the conduct of a man seems most reprehensible, as when one of his colleagues Menahem left the Synhedrion to take service under the tyrant Herod, Hillel holds to this advice: "Judge not thy neighbor until thou art in his place."

Many a tale is narrated of Hillel's patience, unfailing courtesy and tact, tolerance and humility, even under the greatest provocation. The man who bet 400 Zuz that he would break Hillel's patience by silly and far-fetched questions lost his own temper at the consideration with which he was treated. And so the proverb became current, "Patience is worth 400 Zuz." And other tales are told of Hillel's considerate dealing with heathens who wished to embrace Judaism, in contrast to the harsh treatment meted out to them by his contemporary Shammai.

His wife, we learn, was a fit helpmeet to the sage and saint. Their domestic life was a perfect harmony. Once on returning from a journey[95] Hillel heard a sound of quarreling in the neighborhood of his house. "I am certain," said he, "that this noise does not proceed from my home." On another occasion Hillel sent his wife a message to prepare a sumptuous meal for an honored guest. At the appointed hour Hillel and his guest arrived. But the meal was not ready. "Why so late?" asked Hillel. "I prepared a banquet," the wife replied, "according to your desire. But I learned that a couple were to be wedded to-day and they were too poor to provide a marriage feast, so I gave them our meal for their wedding banquet." "Ah, my dear wife, I guessed as much."

But the greatest and most constant hospitality was shown by Hillel to a guest who was always with him and uppermost in his thoughts. Every day it was his habit to withdraw for a while for private meditation. "Whither art thou going?" asked his colleagues and disciples. "I have a guest to whom I must show attention." "Who is this guest?" "My soul," was the solemn reply; "to-day it is with me, to-morrow the heavenly visitant may be departed and returned home."

Is it any wonder that, after forty years of activity in the Patriarchate, when Hillel died (in the year 10 of the common era), men said of him: "Meek and humble-minded, a saint has departed from among us, a disciple of Ezra the Scribe." The title fitted his career, for he came like Ezra from Babylon to Palestine and like Ezra he restored the Law when it was threatened with destruction. Great as a student, he was great also as an inspirer of other students. He left eighty distinguished disciples, of whom the youngest was that famous Jochanan ben Zakkai who became the savior of Judaism at the destruction of the second Temple.

Editors' Note—Dr. Hyamson's portrait of Hillel is the first in a series of character sketches of Jewish Worthies to appear in The Menorah Journal. The second paper will be on Hillel's disciple, Jochanan ben Zakkai.

By William M. Blatt

William M. Blatt (born in Orange, N.J., in 1876)

was educated in the public schools of Boston, and received his degree

of LL.B. from Boston University Law School in 1897. Besides being

engaged with the law in Boston and contributing to a number of legal

periodicals, Mr. Blatt is also devoted to letters and has published a

number of plays, including "Husbands on Approval," and many one-act

playlets, including "The Danger of Ideals," which have been given

professional performance.

William M. Blatt (born in Orange, N.J., in 1876)

was educated in the public schools of Boston, and received his degree

of LL.B. from Boston University Law School in 1897. Besides being

engaged with the law in Boston and contributing to a number of legal

periodicals, Mr. Blatt is also devoted to letters and has published a

number of plays, including "Husbands on Approval," and many one-act

playlets, including "The Danger of Ideals," which have been given

professional performance.Characters: Shylock, Jessica, Antonio, Gratiano, Portia, Isaac, a servant of Shylock.

Scene: A street in Venice.

Time: An afternoon, two years after the last act of "The Merchant of Venice."

As curtain rises, Portia and Gratiano discovered standing and looking down the street, Gratiano pointing.

| Gratiano | Now Lady Portia look a long way off And see if you can recognize a friend. |

| Portia | A friend? One person only do I see— A man, quite old, who hobbles with a staff. |

| Gratiano | He is the one I mean. Now look again And try to recognize his face, his beard. |

| Portia | Why, is it not old Shylock? Sure it is. And met most opportunely, on my word. Now, dear Gratiano, with this icy heart We must needs waste a score or two of words. |

| Gratiano | To make him help his daughter Jessica? |

| Portia | That is the task. |

| Gratiano | Too much for Hercules. |

| (Enter Shylock.) | |

| Portia | A moment, Shylock, of your precious time. You must remember meeting me before. |

| Shylock | Remember, nay then, how could I forget The noble judge who spoke so clean and fair And took away on quibbles all I owned. |

| Portia | Not all, good Shylock, half of it remained. |

| Shylock | Oh, true, I thank you for the half you left. I thank that kindly merchant, him that begged The Duke to quite remit the City's fine Which never would have done him any good— I thank him for accepting what was all He could have claimed, the half of my estate. |

| Portia | In trust—— |

| Shylock | I know. In trust until I die. And trust Antonio to eat it up. Is it not known that when he takes a risk [97]Of more than common danger and doth lose, He makes a record that he did invest A part of my belongings in the venture? Belike by now there's not a ducat left. For that however I have naught but joy Because it means that she who was my daughter And that Lorenzo who's her paramour Will, when I die, inherit penury. |

| Gratiano | But if Antonio's trust should disappear They still would come by all you leave yourself; 'Twas thus the Duke decreed. |

| Shylock | I know a thing Or two that I could tell and make the face Of son Lorenzo somewhat longer grow. |

| Gratiano | Faith, often did Lorenzo say to us "The Jew will find a way to cheat me yet." |

| Shylock | To cheat him out of what? The gold he earned By robbing me, debauching my—my child? |

| Portia | Nay, let us not be quarreling, old man, I have a message that I want to give. |

| Shylock | No message from my daughter—none to me. |

| Portia | I meant not message, what I have is news. Poor Jessica has come to sorry straits. Her husband, having heard of what you spoke, The loss of what Antonio received, The tricks you have been playing with your own, Fell out with Jessica; they came to words; From words, they say, to blows. And so it seems He left her in a pitiable state. |

| Shylock | (laughing wildly) Good, good, good, good. I prithee tell me more. |

| Gratiano | The fiends fly off with thee. Hast thou a heart And canst thou hear the sorrows of thy child In laughter and with joy? |

| Shylock | She is no child Of mine. She is a wench who lied and stole Repaid my love with treason. Broke my heart And left me weakened for mine enemies To ruin and to taunt. Tell me the rest, Leave not a portion out. Describe her pain, Her hunger, her remorse. I would know all. |

| Portia | The font has failed to change thy cruel soul; Thou art a Christian, Shylock, but in name. |

| Shylock | Well, blame thy sacred water. Blame not me. |

| Gratiano | And so poor Jessica must starve and die? |

| Shylock | Why, no. For you and she (pointing to Portia) should be her friends. [98]You Christians will not let a Christian fall. |

| Gratiano | Now there we cut the venom from thy tongue For Jessica will not accept our aid. |

| Portia | Indeed, old man, we know not where she is. We told you, that you might go search for her. Bassanio did offer her employment But she refused, belike because her shame Would not permit that we should see her shame. And so she fled. |

| Gratiano | And may yet be alive. |

| Shylock | These circumstances you should tell unto Lorenzo. 'Twas he took her upon himself For better or for worse. Fare you well. I have affairs that interest me more. |

| Gratiano | Come, Lady Portia. 'Tis a waste of time. The Bible says that God did choose the Jews But says not what it was He chose them for. Our ancient friend hath made it clear to me That they were chosen by our gracious Lord To be a kind of warning and example Of what a misbeliever may become. |

| Portia | Thou wilt not save thy daughter? |

| Shylock | Lady fair, In this peculiar and imperfect world The virtues are divided into parts: For instance, mercy. Some do practice it, And some do merely preach. A third there are Whose only contribution is to be The text from which the second sermons preach; They neither preach nor practice. Such am I. Farewell. |

| Gratiano | We but insult ourselves to stay. (Exit Portia and

Gratiano. Shylock looks after them. Enter Antonio, sees

Shylock, walks over to him and touches him with his stick.

Shylock turns.) |

| Antonio | Hebrew, have I found thee out at last? Once more thy promises are broken, eh? |

| Shylock | Yes, yes. I pray you—— |

| Antonio | Pray me nothing more. |

| Shylock | Signor Antonio, wait another day. |

| Antonio | Another day. For what? Until you hide A bag of ducats or a jewel case? Your bonds are by a fortnight overdue And day by day your fortune dwindles down. If I should sell the roof above your head And all your land and chattels, they would bring Less than enough to pay me what you owe. |

| [99]Shylock | I prithee not so loud. But you alone Are cognizant of my disastrous state. My name is good. Perchance I may obtain A temporary loan to tide me through. But if my losses come to other ears Before my kinsmen and my ship arrive A bankrupt's ending stares me in the face. Wait, wait Antonio, surely he will come, My cousin Issachar who sailed away. |

| Antonio | Thy cousin Issachar will come no more. He promised to return three weeks ago. |

| Shylock | But think, remember, good Antonio, The vessel could not founder. 'Twas my best, Held in reserve, the last one of my fleet. Issachar swore he knew the very spot Where dusky natives mined the laughing gold And that if I would furnish men and ships The moiety of the cargo would be mine. Perhaps he is a little while delayed. |

| Antonio | Perhaps another theory will fit. Perhaps your kinsman filled the ship with gold And then did point his helm another way. Perhaps in England now he lives at ease And deems the whole is better than a half. Consider, sir, your kinsman is a Jew. |

| Shylock | He will not fail me, for he is my friend. Patience, good sir, patience a day or two. Deal with me kindly as so oft before You treated many an unfortunate. |

| Antonio | Let's have no whining. See you pay my bills No later than to-day. Expect no further time. I have done more than doth in truth become A Christian to oblige a Jew withal. Think not to share the leniency I give To men of Venice of my faith and blood. This case is different. |

| Shylock | But did thy Lord Not preach a creed of brotherhood and love And bid thee treat thy neighbor as thyself? |

| Antonio | He meant our Christian neighbors who reside By right of law and ancient heritage Within the land, but not the tribe who do Usurp the places of their betters. No! |

| Shylock | I am a Christian, made so by your Church. Your own priest said so and it must be true. |

| Antonio | 'Twas but a form to bend thy haughty will. In heart and manner thou art still a Jew. [100]They should be glad that they can here remain To practice sacrilege, and cheat, and fawn. I marvel we can be so tolerant. |

| Shylock | The God who made this land and you and me Mocks at your selfish, mean, philosophy. When you or yours can build a mountain peak Or add a grain unto the universe Then talk of this fair ground as your domain. The earth is one and rests within His hand; The great and small His erring children are, But we who from Yisrael claim descent Are now the eldest of the family. The God of Justice never slumbereth. Jehovah is His name; His will be done. |

| Antonio | Mumble thy prayers if that affords relief, But if by sundown I am not repaid Another Moses must thou be and bring Another set of miracles from heaven Or lose the very coat from off thy back. By sundown—but a few short minutes hence. (Exit Antonio) |

| Shylock | Finished—almost finished—almost done. I see the wave that soon above my hopes, My fears, my sorrows, and my broken heart, Will roll in cruel triumph. I'm content. A long and troubled record I shall leave Of struggles in the dark 'gainst many foes. I begged for light to see my duty clear To see the purpose of my suffering To see the end that my Creator served In heaping hills of torment on my head. The light has never come. But now ere long I must be called where all shall be made clear. Till then a few weeks more of faith in Him A few weeks more with an unfalt'ring tongue To praise His wisdom though its end be hid. A few weeks more to walk within His law. |

| (Starts to walk off. Enter Jessica in disordered dress and manner.) | |

| Jessica | Father! |

| Shylock | Back! Away! Dare not to touch me. |

| Jessica | A word, a single word and I will go. |

| Shylock | (trying to wrest his arm from her grasp) Let be I say. |

| Jessica | Nay, but I cannot leave. I know not how much time I have to live. I marvel that this body thin and frail [101]Has so long stood th' innumerable shocks Which in my married life it hath endured. Death must be near, it stretcheth out its arms, And I in answer have extended mine. |

| Shylock | Come not to me for money. Had I all The wealth of Sheba's mines I would not pay A mite to save thy fallen soul from hell. The potter's field may have thy rotten bones And owls and jackals pray for thy repose. |

| Jessica | 'Tis not for gold I beg but for thy love. I threw it from me like an orange sucked And turned to grasp the shining fruit that he, Lorenzo, pictured to mine eyes. Ah me, How bitter, hard and worthless to the taste Hath been that substitute. The marriage moon Had scarce grown full before my body bore The marks of coward blows. |

| Shylock | Ha! Ha! That's well. |

| Jessica | I have not known a single kindly word, I scarce have heard him call me by my name Since less than four weeks after we were wed. |

| Shylock | (gloatingly rubbing his hands) Hm! |

| Jessica | Oh father, why was I not told before That we and all our people are accurst; That those to whom we give our love and trust Curse us and loathe us with a dreadful hate, A hate that neither reason can assuage Nor conduct make amends for. Awful fate, That makes the very children of the street With circle eyes point at us in contempt, And people who have never heard our names Thirst for our blood and menace us with death! |

| Shylock | So thou didst think a priestly comedy Could make Lorenzo love his Jewish wife? |

| Jessica | I could have died for him. For him I fled And stole your wealth and helped your enemies. Why could he not have been a little kind? |

| Shylock | (chuckling) Come tell me how he beat you. Tell me that. |

| Jessica | Have pity, father. |

| Shylock | Tell me how he swore. |

| Jessica | Oh, torture me no further. Take me back. Love me not now, but let me win your love A little at a time. No day shall pass But in it I shall do some tiny act That will in time make up a wealth of deeds, And if we both are living long enough The balance will be as it was before. |

| [102]Shylock | Thy pleadings are but wasted, Jessica, Thou canst not gain the end that thou dost seek. For even if I have the foolish will (And I assure thee that I have it not) To bring thee back to all the luxury, The silken clothes, the soft and perfumed beds, The shining jewels of thy girlhood days, I could not. I am almost penniless. |

| Jessica | Poor, and alone, and old! Nay, father dear, Thou couldst not drive me from thee after this Hadst thou the strength of ten. Let us go forth And find a little corner of the earth Where I may work and you may live at peace. |

| Shylock | I need no aid. I want no help from thee. |

| Jessica | Then give me thine. I starve for sympathy. I shall go mad. I saw my baby die And all around me were my husband's friends Who spoke in terms of polished elegance. With formal platitudes and commonplace Regarding me as something curious, A vulgar, noisy creature, lacking taste And proper self-control. While on its bier Lay all the joy that life in promise held. Dead, and my heart within it.(Weeps) |

| (Shylock turns to go, looks back after a step or two, and returns) | |

| Shylock | I did not know the little one was dead. Was it a pretty child? |

| Jessica | A pretty child! A cherub could not be more beautiful. Blue eyes and golden hair. A tiny mouth A dimple in her chin. (Shylock puts his arm around Jessica) |

| Shylock | Thy mother's face belike. So did she look. And how old when it—died? |

| Jessica | A year, a year. |

| (Enter Antonio and Gratiano. Antonio touches Shylock on the shoulder) | |

| Antonio | Well, let us have an end. The time is up. I now demand the payment of my bonds. |

| Shylock | I have not moved since last you spoke to me. |

| Antonio | All's one for that. You had no move to make. Your whole estate is in the bailiff's hands And you yourself may come along with me. |

| Shylock | Where would you take me? |

| Antonio | Why, before the Duke. |

| Shylock | What need of trials? Freely I confess The debts I owe you. Take what you can find. [103]Take ev'ry rag and counter. Take them all. Myself and Jessica must go away. |

| Antonio | Not quite so fast. The law expressly states That I may put you in the debtor's gaol And so I mean to do. |

| Shylock | But good Signor— |

| Antonio | No protest will avail. I know you Jews. You hang together in calamity And help each other while the Christians starve. Let them redeem you and repay my loss. |

| Shylock | Good sir, my kin are very far away And poor as I. |

| Antonio | 'Twill do no good to lie. Write letters. I will see them promptly sent. |

| Shylock | I swear to you Antonio— |

| Gratiano | Wait a while. First tell us if the oath thou art to make Is sworn as Christian or in Hebrew style; Though truly which to give the preference Is matter to discuss. A Jewish oath Thou canst not take for thou hast been baptised, And sooth to say I have a sort of doubt About thy reverence for Christian forms. |

| Shylock | By that great Power who can humble both Hebrew and Christian, I do swear to you That not in all this universe's span Have I a claim on friends or relatives As large as this. Much more have I the right To claim assistance from Antonio Who though he found me keen for my revenge And steadfast in assertion of my rights Can bring no accusation on my head Of underhanded trickery or crime. |

| Gratiano | Because we watch you pretty carefully. |

| Shylock | What say you, sir? You will not keep us here? |

| Antonio | I warned thee once cajoling will not serve. Write out the letters. That's the only way. I'll see that while you tarry in the gaol Your comfort shall not be too much disturbed. Your food shall be according to your wish And other things in reason you may have. |

| Jessica | Good sir, I think you know me, do you not? |

| Antonio | Why, are you not my friend Lorenzo's wife? |

| Jessica | I am the Jessica who married him, But not his wife if wifehood is a state That presupposes more than legal rights. I and Lorenzo are as strangers now [104]And less than strangers, less than enemies. |

| Antonio | I grieve to hear it. |

| Jessica | I would have your grief Not for myself but for my father here. He speaks the truth. He has no more to give. |

| Antonio | Then let him call upon his wealthy friends, The other Jews will trust him if he asks. |

| Jessica | You heard him say he knows not where to sue. |

| Antonio | O, that was but the cunning of his race. |

| Jessica | Unfeeling man! If his deserts are dumb What of your obligation due to me? The Court's decree as you no doubt recall Was that the half of his estate should go To you to hold in trust for me and mine. I charge you now upon your Christian faith To give my father all the residue That will be mine when he shall pass away Or take it for yourself and let him go. |

| Antonio | Three obstacles prevent your sacrifice. The first is that though my intent was fair By bad investments more than half the fund Has disappeared, and all that doth remain Would not suffice to satisfy the bonds. The second, that the sum is payable Upon your father's death, which is not yet. But third and most of all the money goes To you and to your husband, not to you. The gift is joint and neither can alone Claim all himself or any several part. Indeed, I own it frankly, my desire In asking that the Duke should so decree Was not to benefit Lorenzo's wife, A Jewess, who was never aught to me, But solely to befriend Lorenzo's self My coreligionist and distant kin. To give you anything of Shylock's gold Without Lorenzo's will would be a wrong, A breach of trust, a patent injury. And if your separation from his love, As shrewdly I suspect, be fault of yours And growing from thy Jewish wilfulness, It would be most unfaithful and untrue That I should thus reward inconstancy. You see, in honor and before the law I must refuse to do as you request. |

| Jessica | I see that Jesus died in vain for you. His Jewish heart, with pity for the low [105]And meek and humble broke upon the cross And for a time the magic of his words Restrained the beast in Gentile followers, But soon the kindly Stoic lost his sway And cruel bigots in his Jewish name, By his offenceless, mild authority Took fire and sword and hatred for their flag. |

| Antonio | My girl, there is a law 'gainst blasphemy. |

| Gratiano | Why stand we here and listen to her spleen? Away with Shylock. Take him to the gaol. |

| Antonio | Come on. |

| Jessica | No! No! |

| Shylock | Resist no more, my child. |

| Jessica | Oh, father, we may never meet again; Your age and suffering cannot endure The shock of this disgrace. |

| Shylock | 'Tis better so. I pray for death. It cannot come too soon. Farewell. |

| Jessica | Farewell. (Throws her arms around him) Yet not a long farewell, I shall not far survive. It is no sin To end a life of misery and shame. |

| Isaac | (behind scenes) Where is my master? Where has Shylock gone? (Enter Isaac.) |

| Gratiano | Here fellow, here he is. With Jessica He poses like a model for the arts. |

| Isaac | Great news and wonderful. His ship is here And laden full of gold. The mine is found And Issachar and he are princely rich. This cargo is the greatest that has come To Venice since the city first began. |

| Antonio | I do rejoice to hear it. Truly Jew I have no wish to do thy body harm But thou and thy relations are well known To be so deep in craft and villainy That to recover what is justly due We Christians must resort to rigid means. Go freely with thy daughter. Later on When ev'rything's in order I'll return And you may pay me what the balance is. |

| (Exit Antonio and Gratiano, followed by Isaac. Shylock still stands expressionless with Jessica's arms around him.) | |

It is these young French Jews of immigrant parentage, students and professional men, who organized themselves, about two years ago, in an "Association des Jeunes Juifs," known by its initials as A. J. J. The aim of that organization, which is non-partisan in Jewish affairs, is both cultural and practical. It publishes a monthly by the name of "Les Pionniers," and occasionally holds debates and lectures on various Jewish topics. It also carries on a program of social work among the immigrant Jews. I might perhaps give a clearer idea of the object of the A. J. J. by reproducing their following declaration: "Notre But.—Nous voulons nous affirmer 'Juifs' sans forfanterie, mais avec fermeté; cultiver, développer parmis nous, faire connaître au dehors, l'âme juive; nous éduquer mutuellement; demander, par les voies légales, le respect, la justice pour tous,—fussent-ils juifs; aider nos frères émigrés à l'aquérir la qualité de citoyen; inculquer à nos membres les principes de solidarité et de mutualité." In the summer of 1913, Dr. Nahum Slouszch of the Sorbonne submitted to the society a scheme for more extensive activities, both Jewish[107] and patriotic in their scope, namely, the participation in educational and social work among the indigenous Jews of the French possessions in Africa.

In his religious life the Jew of the Roman Ghetto resembles the Lithuanian rather than the Western European. His religious activity, to be sure, is restricted to the prayer services of the Temple, but his Temple is more like a Beth Midrash than a symphony hall and lyceum. Living within a Catholic environment, his religion has been preserved as something positive, tangible, and powerful; and if it is no longer an inspiring influence within him, it exists at least as a reality outside of him. The religious institutions and instrumentalities are looked upon by him as something hallowed and consecrate. The synagogue is spoken of as the "sacro tempio" and the rabbi, referred to by the Hebrew words "Morenu Harav," is looked up to in matters religious as if he were the incumbent of the throne of Moses. The place of worship is opened three times a day for the traditional number of the daily public prayers, and young men as well as old, unwashed and in their working garments, repair there directly from their work to hear the "sacra messa," as the services are sometimes termed by them. Most of the younger Jews are unable to read the Hebrew prayers, some read without understanding them; but they all know a few selected prayers by heart which they recite aloud with many interesting gesticulations[108] and genuflections, while in the pulpit the Chasan reads the services from a prayer-book printed in Livorno, chanting them in a monotonous sing-song not unlike what one often hears in the chapels of St. Peter.

It is therefore not surprising that among the native Italian Jews there should arise on the part of the young educated elements a desire to convert that latent Jewish sentiment into some form of practical and useful activity. A society of Jewish youth in Italy has already existed for about three years during which time two conventions were held. A number of commendable resolutions were passed about the improvement of Jewish education among the Italian Jews and especially the advancement of the study of the Hebrew language among them. Zionism was warmly endorsed, though the society as a whole did not commit itself officially to the cause. Like the A. J. J. of Paris, the Italian organization also purports to act as intermediaries between the Italian government and the native Jewish population of Tripoli. In Rome there is a local organization of Jewish students, devoted to the study of Hebrew literature, and is rather of cosmopolitan complexion, being composed of Italian, Greek, German, and Russian Jews. The moving spirit of that circle was a brilliant Russian Jew, who had graduated in law from the University of Rome.

The enthusiasm for Judaism, everywhere in a process of growth, manifests itself in its early stages in study and self-cultivation; it assumes a more concrete form, in its later stages, of some communal or social activity; and if that development keeps on uninterruptedly it finally consummates in Zionism. This development, it must be admitted, is not a spontaneous and self-directive movement. In no small measure, it is everywhere stimulated by the growing tendency on the part of non-Jews in almost every country to appraise the Jew according to his racial origin, an appraisal which results in a feeling not necessarily hostile, but in most cases neutral and sometimes even favoring the racial and cultural peculiarity, indestructible and impermiscible, of the Jewish element. It is this external stimulus, rather than any internal impulse, that is responsible for the unfolding of the national spirit among Jewish students and the assertion of their selfhood.

None the less, their self-assertion has nowhere reached the extreme of spiritual alienation from their environment. There is nothing more remarkable in the character of Jewish youth of the present day, even among those who were born and raised in East European ghettos, than the spiritual and intellectual snugness in which they find themselves, in what should have been expected to remain to them a foreign environment. The residual estrangement of the Jewish soul from everything that is non-Jewish, which our forefathers in the past had figuratively designated with what Jewish mysticism called the "Captivity of the Shekinah," has totally disappeared. The individual Jew of to-day, while sharing in the sublimated consciousness of the race as a whole, does not in any conscious or subliminal way feel himself to be personally identified with it; whence the hesitation on the part of the majority of Jewish students to participate actively in Zionism even though they would all admit it to be the logical sequel of Jewish history.

For Zionism to them can never become a personal ideal, something requisite for the salvation of their souls. It can at its best appeal to them, in so far as they are consciously Jewish, as the cause of the nation as a whole; and consequently the mere suspicion that their affiliation with[110] the movement might be held up against them as an impugnment of their loyalty to the land of their birth and abode is sufficient to keep them aloof from it. It was very interesting for me to notice how everywhere, after a long manœuvre of Zionist discussions with good Jewish young men, they would finally halt at their unshakable position that Zionists might arouse the suspicion of their Gentile neighbors as to the loyalty and patriotism of the Jews. Where people are obsessed by the fear of being misunderstood in doing what they otherwise think to be good and impeccable, no arguments, of course, can avail. They are in this respect characteristically Jewish. In their Brand-like racial frame of mind, the Jews could never stop midway between the two antipodes of roving world-citizenry and hidebound mono-patriotism. It is probable that their attitude will change as soon as it is generally realized that personal devotion and loyalty to two causes are not psychologically a self-deception, and that the serving of two masters is not a moral anomaly unless, as in the original adage, one of the masters be Satanic.

MARVIN M. LOWENTHAL (born in Bradford, Pa., in 1890)

is at present a Senior in the University of Wisconsin. He has won the

Wisconsin Menorah Society Prize twice—in 1912 for an essay on "The

Jew in the American Revolution," and in 1914 for the essay on

"Zionism" here published for the first time. Mr. Lowenthal is now the

President of the Wisconsin Zionist Society.

MARVIN M. LOWENTHAL (born in Bradford, Pa., in 1890)

is at present a Senior in the University of Wisconsin. He has won the

Wisconsin Menorah Society Prize twice—in 1912 for an essay on "The

Jew in the American Revolution," and in 1914 for the essay on

"Zionism" here published for the first time. Mr. Lowenthal is now the

President of the Wisconsin Zionist Society.| "Oh God, the heathen are come into Thine inheritance; |

| Thy holy Temple have they defiled; |

| They have laid Jerusalem in heaps."[1] |

This picture reveals the typical and traditional attitude of the Jew toward the land of his forefathers. Taught as children in the Cheder to turn their thoughts and desires toward Palestine; devoting themselves as men to the study of the Law and the Prophets and to the building upon this study of the vast Talmudic structure, until a spiritual Land of the Book may be said to have been created wherein they continually dwelt; crystallizing and adopting the Restoration as a dogma of the faith; commemorating with solemn fasts the Ninth of Ab as the anniversary of the destruction of the Temple by Titus; and repeating at each Passover with the pitiful hope of a child, "Next year in Jerusalem," the Jews have bound the memory of Palestine as a sign upon their hands and as frontlets between their eyes. They have indeed written it upon the door-posts of their houses and upon their gates, to the end—that they have wept and prayed. The vision of the prophets, which created and sustained this passionate ideal, itself inhibited the realization by emphasizing the redemption[112] as miraculous, as a consummation to come in its own time without man's effort, and indeed in spite of man's will. And so, except for the sporadic and meteoric fiascos of mock-Messiahs, the Jews—this most practical of people—continued in hope and prayer to watch the centuries creep by. Frequently the hope flowered into the songs of a Judah Halevi or Ibn Gabirol, songs as sweet as have blossomed in the medieval garden; and the prayer found expression in a poignancy attributable only to the racial genius which created the Psalms; but until the nineteenth century the dream preserved all the qualities of a dream.

Quoting from his book, "The Jewish State"[2]—a book journalistic in style, but trumpet-toned in the note it sounded for political Zionism—Theodor Herzl offered the following definition of Zionism after the first Zionist Congress (1897): "Zionism has for its object the creation of a home, secured by public rights, for those Jews who either cannot or will not be assimilated in the country of their adoption."[3] Zionism, in a word, is not the last truism in a weary debate, nor a new verse to an old song; it is, on the contrary, a definite answer to a perplexing and imperative question. What are these Jews who cannot or will not be assimilated, and why cannot or will not they be assimilated? This question constitutes what is known as the Jewish problem, or, for those who deny or dislike the term, the Jewish position; and this question must first be fully stated before the Zionist or any other answer can be intelligible.

That the existence of a separate, recalcitrant, and even obnoxious nation within a nation did not constitute a problem for the medievals may be attributable to two reasons: (1) the medieval theory of life accentuated a hierarchical order of existence—a theory that found expression in feudalism, in Church organization, and in guild and craft life; in pursuance of this theory, the Jews were accorded a recognized and distinct status; (2) furthermore, the Jews were an economic necessity in the times when a ban was laid on money-lending, and they constituted an important economic facility at a little later period when capital could indeed be worked but when rivalry and hatreds rendered communication uncertain.[6] To the maintenance of Jewish solidarity and the preservation of things Jewish qua Jewish, sacrifices culminating in the surrender of life bequeathed to the race a comprehensive martyrology.[7]

Ernest Renan defines a nation as "a great solidarity constituted by the sentiment of the sacrifices that its citizens have made and those they feel prepared to make once more. It implies a past, but is summed up in the present by a tangible fact—the clearly expressed desire to live a common life." In sum, the Jews throughout the Middle Ages, which was prolonged for them until a little less than two hundred years ago, comprised a nation as virtual in point of their own claim and its recognition by other nations as in the days when they were established in Palestine. Renaissance, Reformation, and the rediscovery of the world by science failed to make an impression on the thick ghetto walls; and Jewish isolation, even as late as the eighteenth century, may be vividly realized by thinking of Rousseau and Voltaire in contrast with the contemporary lights of Jewry—Elijah Gaon and Israel Besht,[8] men as medieval as a gargoyle.

The French Revolution with its early philosophy of naturalism and humanism and its later political expression in liberty, equality, and fraternity, razed the physical and spiritual walls of the ghetto and set up[114] the "Jewish problem." Following the Revolution, four currents of thought and action, working both simultaneously and successively, causing, reacting upon, and intermingling with one another, affecting the Jews now favorably and now unfavorably, went into the making of this problem. To deal with Emancipation, Enlightenment, Nationalism, and Anti-Semitism in detail would consume a volume, but an outline of their bearing on the present situation is essential.

The Enlightenment, or Haskalah movement, broadly speaking, comprises the Jewish absorption of secular learning, particularly in literature and science, the abandonment of the study of the Talmud for modern subjects, and the adoption of farm and craft life.[10] Moses Mendelssohn in Germany and Lilienthal in Russia were the first great protagonists of these radical departures; and the movement, which in part led to the demand for Emancipation and in part resulted from it, further removed the differences between Jew and non-Jew, at least from the standpoint of the former, and further removed him from his religious and historical[115] past, perceptibly weakening and in many cases practically destroying the medieval sense of solidarity. Each Jew adopted the culture of his native country, and so one Jew became virtually a foreigner to another. Haskalah, in a word, is a looking outward on the part of the Jew; for all its virtues this movement had the consequence of blunting racial consciousness and blurring racial identity.

In its restricted sense, anti-Semitism is a scientific stick used to beat the Jewish dog with. After impartial, impersonal scientific investigation, French and German scholars[11] demonstrated the racial inferiority of the Semite to the Aryan, enumerated the inherent Semitic qualities as greed, special aptitude for money-making, aversion to hard work, clannishness, obstrusiveness, lack of social tact and of patriotism, the tendency to exploit and not to be overly honest. Ernest Renan adequately sums up the anti-Semite position when he claims for the Aryans all the great military, political, and intellectual movements of history.[12] The Semites never had a comprehension of civilization in the sense in which the Aryan understands the word; they were at no time public-spirited.[13] In fact, intolerance was the natural consequence of Semitic monotheism.[14]

In the wider sense,[15] anti-Semitism is the modern word for the old and apparently ineradicable hatred of the Jew, partly dependent, as G. F.[116] Abbott well shows,[16] not only upon Christian faith, but upon the Christian frame of mind and feeling—a hatred to which the Nationalism of the nineteenth century furnished a reasonable fuel, which found a social expression in ostracism and rioting[17] and a political expression in the formation of the Christian Socialist Party in Germany (1878), and similar parties in Austria and Hungary (1882-99), seeking the suppression of equal rights for Jews, the Dreyfus affair in France (1895), and the open, violent persecutions in Roumania—all aimed at annulling the privileges granted by the Emancipation. Clerical, economic, and social opposition to the Jews combined to support the nationalistic contention summed up in the words of Heinrich von Treitschke (Professor of History, University of Berlin): "Die Juden sind unser Unglück."[18] This essay is not concerned with the truth of the contention; suffice that it is advanced, supported, and acted upon.