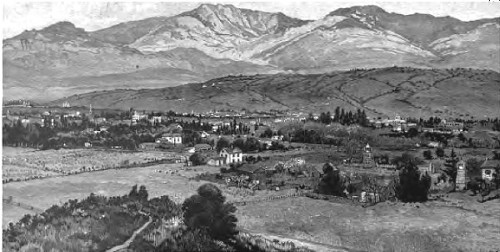

SANTA BARBARA.

SANTA BARBARA.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Our Italy, by Charles Dudley Warner This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Our Italy Author: Charles Dudley Warner Release Date: April 5, 2009 [EBook #28506] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OUR ITALY *** Produced by Bryan Ness, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.)

SANTA BARBARA.

SANTA BARBARA.

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, FRANKLIN SQUARE

Copyright, 1891, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

CHAP. PAGE

I. HOW OUR ITALY IS MADE 1

II. OUR CLIMATIC AND COMMERCIAL MEDITERRANEAN 10

III. EARLY VICISSITUDES.—PRODUCTIONS.—SANITARY CLIMATE 24

IV. THE WINTER OF OUR CONTENT 42

V. HEALTH AND LONGEVITY 52

VI. IS RESIDENCE HERE AGREEABLE? 65

VII. THE WINTER ON THE COAST 72

VIII. THE GENERAL OUTLOOK.—LAND AND PRICES 90

IX. THE ADVANTAGES OF IRRIGATION 99

X. THE CHANCE FOR LABORERS AND SMALL FARMERS 107

XI. SOME DETAILS OF THE WONDERFUL DEVELOPMENT 114

XII. HOW THE FRUIT PERILS WERE MET.—FURTHER DETAILS OF LOCALITIES 128

XIII. THE ADVANCE OF CULTIVATION SOUTHWARD 140

XIV. A LAND OF AGREEABLE HOMES 146

XV. SOME WONDERS BY THE WAY.—YOSEMITE.—MARIPOSA TREES.—MONTEREY 148

XVI. FASCINATIONS OF THE DESERT.—THE LAGUNA PUEBLO 163

XVII. THE HEART OF THE DESERT 177

XVIII. ON THE BRINK OF THE GRAND CAÑON.—THE UNIQUE MARVEL OF NATURE 189

APPENDIX 201

INDEX 219

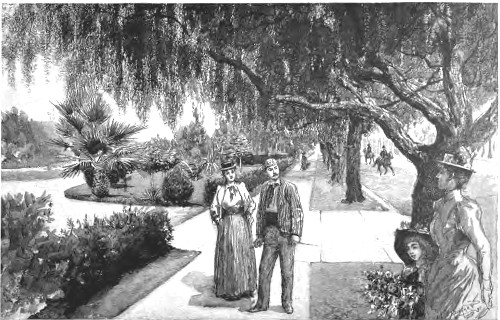

SANTA BARBARA Frontispiece

PAGE

MOJAVE DESERT 3

MOJAVE INDIAN 4

MOJAVE INDIAN 5

BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF RIVERSIDE 7

SCENE IN SAN BERNARDINO 11

SCENES IN MONTECITO AND LOS ANGELES 13

FAN-PALM, LOS ANGELES 16

YUCCA-PALM, SANTA BARBARA 17

MAGNOLIA AVENUE, RIVERSIDE 21

AVENUE LOS ANGELES 27

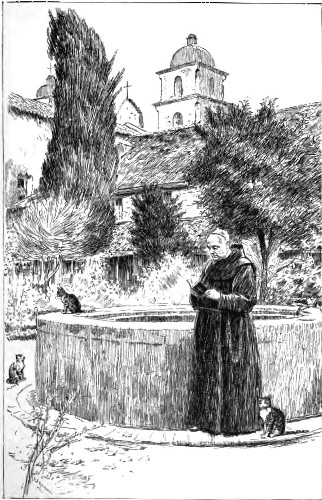

IN THE GARDEN AT SANTA BARBARA MISSION 31

SCENE AT PASADENA 35

LIVE-OAK NEAR LOS ANGELES 39

MIDWINTER, PASADENA 53

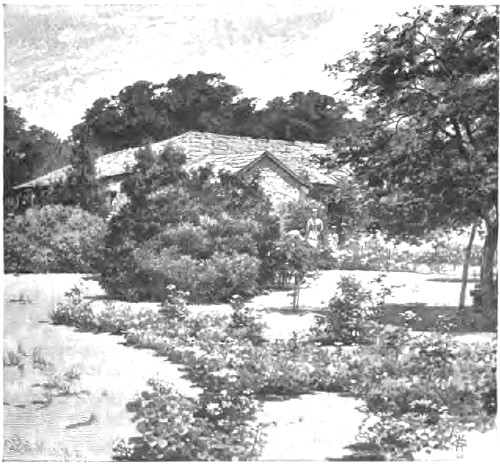

A TYPICAL GARDEN, NEAR SANTA ANA 57

OLD ADOBE HOUSE, POMONA 61

FAN-PALM, FERNANDO ST. LOS ANGELES 63

SCARLET PASSION-VINE 68

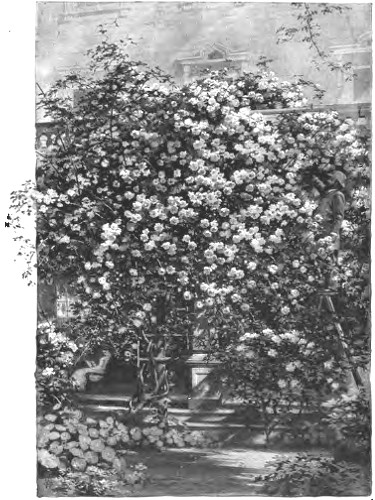

ROSE-BUSH, SANTA BARBARA 73

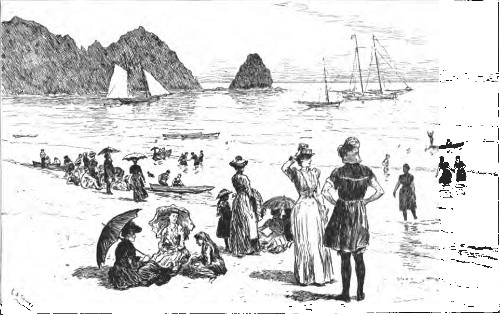

AT AVALON, SANTA CATALINA ISLAND 77

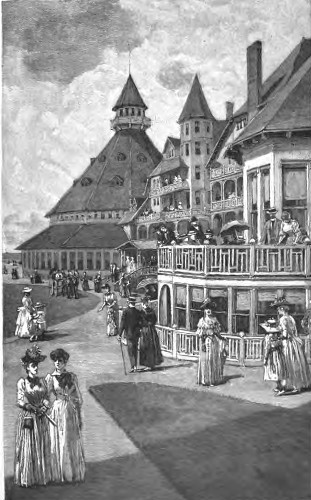

HOTEL DEL CORONADO 83

OSTRICH YARD, CORONADO BEACH 86

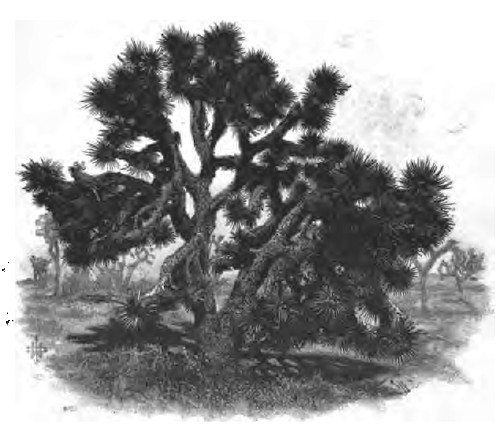

YUCCA-PALM 92

DATE-PALM 93

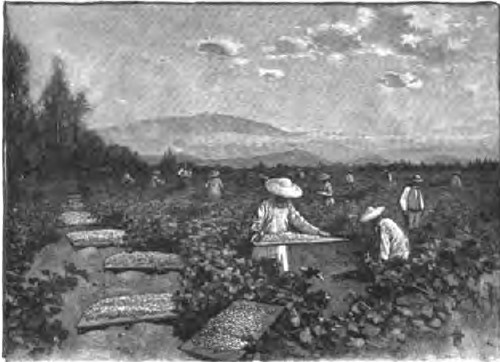

RAISIN-CURING 101

IRRIGATION BY ARTESIAN-WELL SYSTEM 104

IRRIGATION BY PIPE SYSTEM 105

GARDEN SCENE, SANTA ANA 110

A GRAPE-VINE, MONTECITO VALLEY, SANTA BARBARA 116

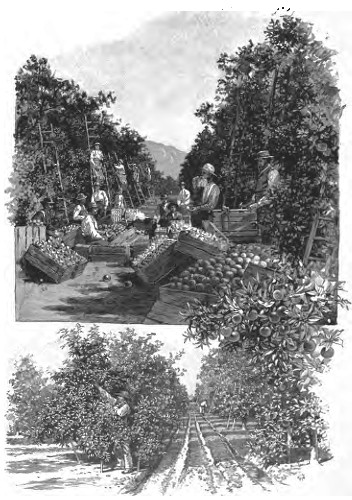

IRRIGATING AN ORCHARD 120

ORANGE CULTURE 121

IN A FIELD OF GOLDEN PUMPKINS 126

PACKING CHERRIES, POMONA 131

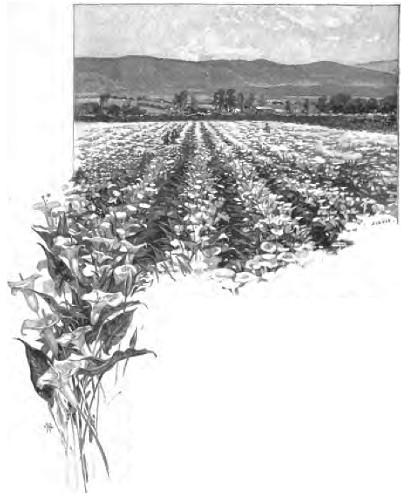

OLIVE-TREES SIX YEARS OLD 136

SEXTON NURSERIES, NEAR SANTA BARBARA 141

SWEETWATER DAM 144

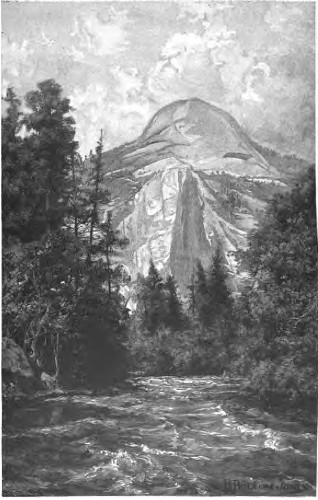

THE YOSEMITE DOME 151

COAST OF MONTEREY 155

CYPRESS POINT 156

NEAR SEAL ROCK 157

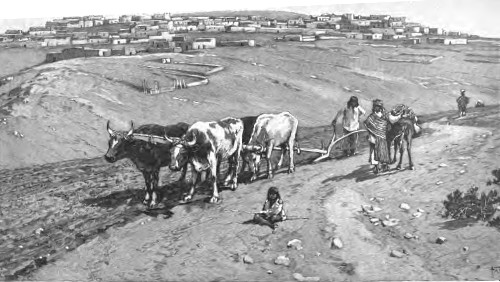

LAGUNA—FROM THE SOUTH-EAST 159

CHURCH AT LAGUNA 164

TERRACED HOUSES, PUEBLO OF LAGUNA 167

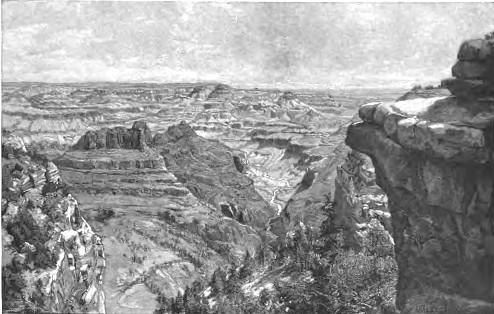

GRAND CAÑON ON THE COLORADO—VIEW FROM POINT SUBLIME 171

INTERIOR OF THE CHURCH AT LAGUNA 174

GRAND CAÑON OF THE COLORADO—VIEW OPPOSITE POINT SUBLIME 179

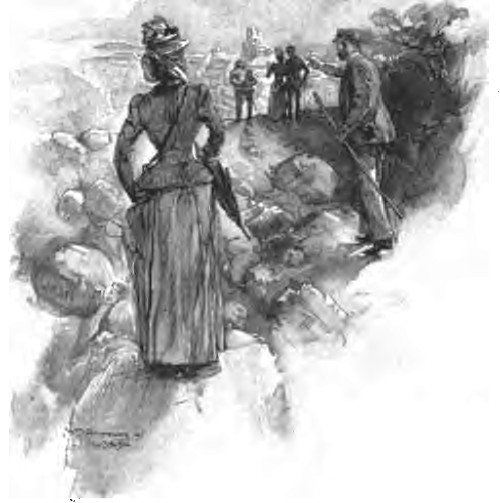

TOURISTS IN THE COLORADO CAÑON 183

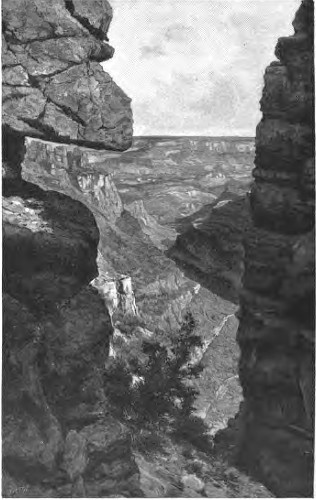

GRAND CAÑON OF THE COLORADO—VIEW FROM THE HANSE TRAIL 191

The traveller who descends into Italy by an Alpine pass never forgets the surprise and delight of the transition. In an hour he is whirled down the slopes from the region of eternal snow to the verdure of spring or the ripeness of summer. Suddenly—it may be at a turn in the road—winter is left behind; the plains of Lombardy are in view; the Lake of Como or Maggiore gleams below; there is a tree; there is an orchard; there is a garden; there is a villa overrun with vines; the singing of birds is heard; the air is gracious; the slopes are terraced, and covered with vineyards; great sheets of silver sheen in the landscape mark the growth of the olive; the dark green orchards of oranges and lemons are starred with gold; the lusty fig, always a temptation as of old, leans invitingly over the stone wall; everywhere are bloom and color under the blue sky; there are shrines by the way-side, chapels on the hill; one hears the melodious bells, the call of the vine-dressers, the laughter of girls.[Pg 2]

The contrast is as great from the Indians of the Mojave Desert, two types of which are here given, to the vine-dressers of the Santa Ana Valley.

Italy is the land of the imagination, but the sensation on first beholding it from the northern heights, aside from its associations of romance and poetry, can be repeated in our own land by whoever will cross the burning desert of Colorado, or the savage wastes of the Mojave wilderness of stone and sage-brush, and come suddenly, as he must come by train, into the bloom of Southern California. Let us study a little the physical conditions.

The bay of San Diego is about three hundred miles east of San Francisco. The coast line runs south-east, but at Point Conception it turns sharply east, and then curves south-easterly about two hundred and fifty miles to the Mexican coast boundary, the extreme south-west limits of the United States, a few miles below San Diego. This coast, defined by these two limits, has a southern exposure on the sunniest of oceans. Off this coast, south of Point Conception, lies a chain of islands, curving in position in conformity with the shore, at a distance of twenty to seventy miles from the main-land. These islands are San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, Anacapa, Santa Barbara, San Nicolas, Santa Catalina, San Clemente, and Los Coronados, which lie in Mexican waters. Between this chain of islands and the main-land is Santa Barbara Channel, flowing northward. The great ocean current from the north flows past Point Conception like a mill-race, and makes a suction, or a sort of eddy. It approaches nearer the coast in Lower California, where the return current,[Pg 3] which is much warmer, flows northward and westward along the curving shore. The Santa Barbara Channel, which may be called an arm of the Pacific, flows by many a bold point and lovely bay, like those of San Pedro, Redondo, and Santa Monica; but it has no secure harbor, except the magnificent and unique bay of San Diego.

MOJAVE DESERT.

MOJAVE DESERT.

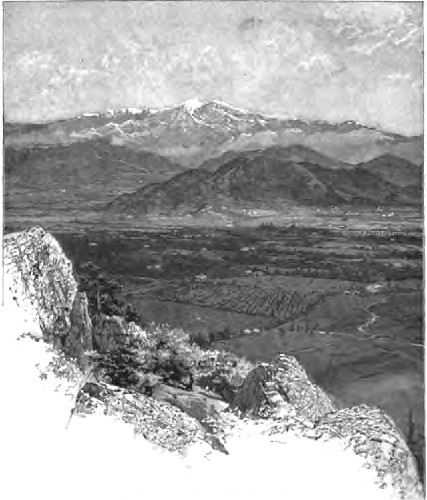

The southern and western boundary of Southern California is this mild Pacific sea, studded with rocky and picturesque islands. The northern boundary of this region is ranges of lofty mountains, from five thousand to eleven thousand feet in height, some of them always snow-clad, which run eastward from Point Conception nearly to the Colorado Desert. They are parts of the Sierra Nevada range, but they take[Pg 4] various names, Santa Ynes, San Gabriel, San Bernardino, and they are spoken of all together as the Sierra Madre. In the San Gabriel group, "Old Baldy" lifts its snow-peak over nine thousand feet, while the San Bernardino "Grayback" rises over eleven thousand feet above the sea. Southward of this, running down into San Diego County, is the San Jacinto range, also snow-clad; and eastward the land falls rapidly away into the Salt Desert of the Colorado, in which is a depression about three hundred feet below the Pacific.

The Point Arguilles, which is above Point Conception, by the aid of the outlying islands, deflects the cold current from the north off the coast of Southern California, and the mountain ranges from Point Conception east divide the State of California into two climatic regions, the southern having more warmth, less rain and fog, milder winds, and less variation of daily temperature than the climate of Central California to the north.[A] Other striking climatic conditions are produced by the daily interaction of the Pacific Ocean and the Colorado Desert, infinitely diversified in minor particulars by the exceedingly broken character of the region—a jumble of bare mountains, fruitful foot-hills, and rich valleys. It would be[Pg 5] only from a balloon that one could get an adequate idea of this strange land.

The United States has here, then, a unique corner of the earth, without its like in its own vast territory, and unparalleled, so far as I know, in the world. Shut off from sympathy with external conditions by the giant mountain ranges and the desert wastes, it has its own climate unaffected by cosmic changes. Except a tidal wave from Japan, nothing would seem to be able to affect or disturb it. The whole of Italy feels more or less the climatic variations of the rest of Europe. All our Atlantic coast, all our interior basin from Texas to Manitoba, is in climatic sympathy. Here is a region larger than New England which manufactures its own weather and refuses to import any other.

With considerable varieties of temperature according to elevation or protection from the ocean breeze, its climate is nearly, on the whole, as agreeable as that of the Hawaiian Islands, though pitched in a lower key, and with greater variations between day and night. The key to its peculiarity, aside from its southern exposure, is the Colorado Desert. That desert, waterless and treeless, is cool at night and intolerably hot in the daytime, sending up a vast column of hot air, which cannot escape eastward, for Arizona manufactures a like column. It flows high above the mountains westward till it strikes the Pacific and parts with its heat,[Pg 6] creating an immense vacuum which is filled by the air from the coast flowing up the slope and over the range, and plunging down 6000 feet into the desert. "It is easy to understand," says Mr. Van Dyke, making his observations from the summit of the Cuyamaca, in San Diego County, 6500 feet above the sea-level, "how land thus rising a mile or more in fifty or sixty miles, rising away from the coast, and falling off abruptly a mile deep into the driest and hottest of American deserts, could have a great variety of climates.... Only ten miles away on the east the summers are the hottest, and only sixty miles on the west the coolest known in the United States (except on this coast), and between them is every combination that mountains and valleys can produce. And it is easy to see whence comes the sea-breeze, the glory of the California summer. It is passing us here, a gentle breeze of six or eight miles an hour. It is flowing over this great ridge directly into the basin of the Colorado Desert, 6000 feet deep, where the temperature is probably 120°, and perhaps higher. For many leagues each side of us this current is thus flowing at the same speed, and is probably half a mile or more in depth. About sundown, when the air on the desert cools and descends, the current will change and come the other way, and flood these western slopes with an air as pure as that of the Sahara and nearly as dry.[Pg 7]

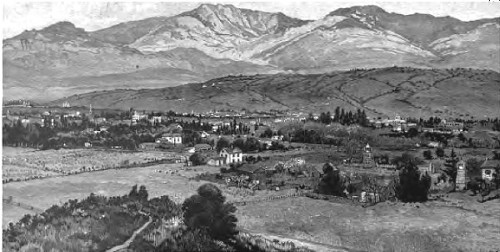

BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF RIVERSIDE.

BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF RIVERSIDE.

"The air, heated on the western slopes by the sea, would by rising produce considerable suction, which could be filled only from the sea, but that alone would not make the sea-breeze as dry as it is. The principal suction is caused by the rising of heated air from the great desert.... On the top of old Grayback (in San Bernardino) one can feel it [this breeze] setting westward, while in the cañons, 6000 feet below, it is blowing eastward.... All over Southern California the conditions of this breeze are about the same, the great Mojave Desert and the valley of the San Joaquin above operating in the same way, assisted by interior[Pg 8] plains and slopes. Hence these deserts, that at first seem to be a disadvantage to the land, are the great conditions of its climate, and are of far more value than if they were like the prairies of Illinois. Fortunately they will remain deserts forever. Some parts will in time be reclaimed by the waters of the Colorado River, but wet spots of a few hundred thousand acres would be too trifling to affect general results, for millions of acres of burning desert would forever defy all attempts at irrigation or settlement."

This desert-born breeze explains a seeming anomaly in regard to the humidity of this coast. I have noticed on the sea-shore that salt does not become damp on the table, that the Portuguese fishermen on Point Loma are drying their fish on the shore, and that while the hydrometer gives a humidity as high as seventy-four, and higher at times, and fog may prevail for three or four days continuously, the fog is rather "dry," and the general impression is that of a dry instead of the damp and chilling atmosphere such as exists in foggy times on the Atlantic coast.

"From the study of the origin of this breeze we see," says Mr. Van Dyke, "why it is that a wind coming from the broad Pacific should be drier than the dry land-breezes of the Atlantic States, causing no damp walls, swelling doors, or rusting guns, and even on the coast drying up, without salt or soda, meat cut in strips an inch thick and fish much thicker."

At times on the coast the air contains plenty of moisture, but with the rising of this breeze the moisture decreases instead of increases. It should be said also that this constantly returning current of air is[Pg 9] always pure, coming in contact nowhere with marshy or malarious influences nor any agency injurious to health. Its character causes the whole coast from Santa Barbara to San Diego to be an agreeable place of residence or resort summer and winter, while its daily inflowing tempers the heat of the far inland valleys to a delightful atmosphere in the shade even in midsummer, while cool nights are everywhere the rule. The greatest surprise of the traveller is that a region which is in perpetual bloom and fruitage, where semi-tropical fruits mature in perfection, and the most delicate flowers dazzle the eye with color the winter through, should have on the whole a low temperature, a climate never enervating, and one requiring a dress of woollen in every month.

[A] For these and other observations upon physical and climatic conditions I am wholly indebted to Dr. P. C. Remondino and Mr. T. S. Van Dyke, of San Diego, both scientific and competent authorities.

Winter as we understand it east of the Rockies does not exist. I scarcely know how to divide the seasons. There are at most but three. Spring may be said to begin with December and end in April; summer, with May (whose days, however, are often cooler than those of January), and end with September; while October and November are a mild autumn, when nature takes a partial rest, and the leaves of the deciduous trees are gone. But how shall we classify a climate in which the strawberry (none yet in my experience equal to the Eastern berry) may be eaten in every month of the year, and ripe figs may be picked from July to March? What shall I say of a frost (an affair of only an hour just before sunrise) which is hardly anywhere severe enough to disturb the delicate heliotrope, and even in the deepest valleys where it may chill the orange, will respect the bloom of that fruit on contiguous ground fifty or a hundred feet higher? We boast about many things in the United States, about our blizzards and our cyclones, our inundations and our areas of low pressure, our hottest and our coldest places in the world, but what can we say for this little corner which is practically frostless, and yet never had a sunstroke, knows nothing of thunder-storms and lightning, never experienced a cyclone,[Pg 11] which is so warm that the year round one is tempted to live out-of-doors, and so cold that woollen garments are never uncomfortable? Nature here, in this protected and petted area, has the knack of being genial without being enervating, of being stimulating without "bracing" a person into the tomb. I think it conducive to equanimity of spirit and to longevity to sit in an orange grove and eat the fruit and inhale the fragrance of it while gazing upon a snow-mountain.

SCENE IN SAN BERNARDINO.

SCENE IN SAN BERNARDINO.

This southward-facing portion of California is irrigated by many streams of pure water rapidly falling from the mountains to the sea. The more important are the Santa Clara, the Los Angeles and San Gabriel, the Santa Ana, the Santa Margarita, the San Luis Rey, the San Bernardo, the San Diego, and, on the Mexican border, the Tia Juana. Many of them go dry or flow underground in the summer months (or, as the Californians say, the bed of the river gets on top), but most of them can be used for artificial irrigation.[Pg 12] In the lowlands water is sufficiently near the surface to moisten the soil, which is broken and cultivated; in most regions good wells are reached at a small depth, in others artesian-wells spout up abundance of water, and considerable portions of the regions best known for fruit are watered by irrigating ditches and pipes supplied by ample reservoirs in the mountains. From natural rainfall and the sea moisture the mesas and hills, which look arid before ploughing, produce large crops of grain when cultivated after the annual rains, without artificial watering.

Southern California has been slowly understood even by its occupants, who have wearied the world with boasting of its productiveness. Originally it was a vast cattle and sheep ranch. It was supposed that the land was worthless except for grazing. Held in princely ranches of twenty, fifty, one hundred thousand acres, in some cases areas larger than German principalities, tens of thousands of cattle roamed along the watercourses and over the mesas, vast flocks of sheep cropped close the grass and trod the soil into hard-pan. The owners exchanged cattle and sheep for corn, grain, and garden vegetables; they had no faith that they could grow cereals, and it was too much trouble to procure water for a garden or a fruit orchard. It was the firm belief that most of the rolling mesa land was unfit for cultivation, and that neither forest nor fruit trees would grow without irrigation. Between Los Angeles and Redondo Beach is a ranch of 35,000 acres. Seventeen years ago it was owned by a Scotchman, who used the whole of it as a sheep ranch. In selling it to the present owner he warned him not to waste time by attempting to farm it; he himself raised no fruit or vegetables, planted no trees, and bought all his corn, wheat, and barley. The purchaser, however, began to experiment. He planted trees and set out orchards which grew, and in a couple of years he wrote to the former owner that he had 8000 acres in fine wheat. To say it in a word, there is scarcely an acre of the tract which is not highly productive in barley, wheat, corn, potatoes, while considerable parts of it are especially adapted to the English walnut and to the citrus fruits.[Pg 13]

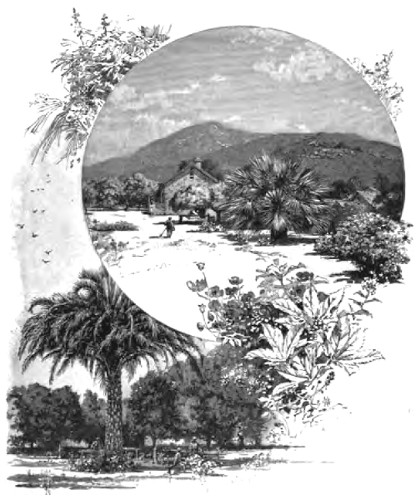

SCENES IN MONTECITO AND LOS ANGELES.

SCENES IN MONTECITO AND LOS ANGELES.

On this route to the sea the road is lined with gardens. Nothing could be more unpromising in appearance than this soil before it is ploughed and pulverized by the cultivator. It looks like a barren waste. We passed a tract that was offered three years ago for twelve dollars an acre. Some of it now is rented to Chinamen at thirty dollars an acre; and I saw one field of two acres off which a Chinaman has sold in one season $750 worth of cabbages.

The truth is that almost all the land is wonderfully productive if intelligently handled. The low ground has water so near the surface that the pulverized soil will draw up sufficient moisture for the crops; the mesa, if sown and cultivated after the annual rains, matures grain and corn, and sustains vines and fruit-trees. It is singular that the first settlers should never have discovered this productiveness. When it became apparent—that is, productiveness without artificial watering—there spread abroad a notion that irrigation generally was not needed. We shall have occasion to speak of this more in detail, and I will now only say, on good authority, that while cultivation, not to keep down the weeds only, but to keep the soil stirred and[Pg 15] prevent its baking, is the prime necessity for almost all land in Southern California, there are portions where irrigation is always necessary, and there is no spot where the yield of fruit or grain will not be quadrupled by judicious irrigation. There are places where irrigation is excessive and harmful both to the quality and quantity of oranges and grapes.

The history of the extension of cultivation in the last twenty and especially in the past ten years from the foot-hills of the Sierra Madre in Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties southward to San Diego is very curious. Experiments were timidly tried. Every acre of sand and sage-bush reclaimed southward was supposed to be the last capable of profitable farming or fruit-growing. It is unsafe now to say of any land that has not been tried that it is not good. In every valley and on every hill-side, on the mesas and in the sunny nooks in the mountains, nearly anything will grow, and the application of water produces marvellous results. From San Bernardino and Redlands, Riverside, Pomona, Ontario, Santa Anita, San Gabriel, Pasadena, all the way to Los Angeles, is almost a continuous fruit garden, the green areas only emphasized by wastes yet unreclaimed; a land of charming cottages, thriving towns, hospitable to the fruit of every clime; a land of perpetual sun and ever-flowing breeze, looked down on by purple mountain ranges tipped here and there with enduring snow. And what is in progress here will be seen before long in almost every part of this wonderful land, for conditions of soil and climate are essentially everywhere the same, and capital is finding out how to store in and bring from the fastnesses of the mountains rivers of clear[Pg 16] water taken at such elevations that the whole arable surface can be irrigated. The development of the country has only just begun.

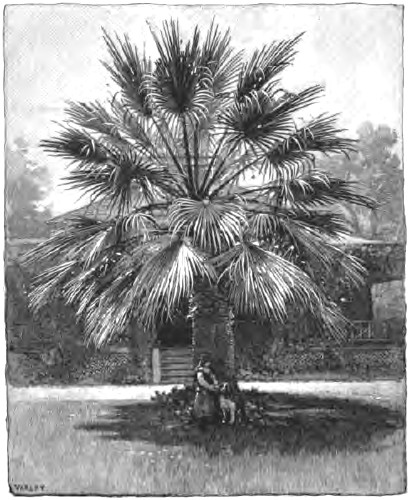

FAN-PALM, LOS ANGELES.

FAN-PALM, LOS ANGELES.

YUCCA-PALM, SANTA BARBARA.

YUCCA-PALM, SANTA BARBARA.

If the reader will look upon the map of California he will see that the eight counties that form Southern California—San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura, Kern, Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Orange, and San Diego—appear very mountainous. He will also notice that the eastern slopes of San Bernardino and San Diego are deserts. But this is an immense area. San Diego County alone is as large as Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island combined, and the amount of arable land in the valleys, on the foot-hills, on the rolling mesas, is enormous, and capable of sustaining a dense population, for its fertility and its yield to the acre under cultivation are incomparable. The reader will also notice another thing. With the railroads now built and certain to be built through all this diversified region, round from the Santa Barbara Mountains to the San Bernardino, the San Jacinto, and[Pg 18] down to Cuyamaca, a ride of an hour or two hours brings one to some point on the 250 miles of sea-coast—a sea-coast genial, inviting in winter and summer, never harsh, and rarely tempestuous like the Atlantic shore.

Here is our Mediterranean! Here is our Italy! It is a Mediterranean without marshes and without malaria, and it does not at all resemble the Mexican Gulf, which we have sometimes tried to fancy was like the classic sea that laves Africa and Europe. Nor is this region Italian in appearance, though now and then some bay with its purple hills running to the blue sea, its surrounding mesas and cañons blooming in semi-tropical luxuriance, some conjunction of shore and mountain, some golden color, some white light and sharply defined shadows, some refinement of lines, some poetic tints in violet and ashy ranges, some ultramarine in the sea, or delicate blue in the sky, will remind the traveller of more than one place of beauty in Southern Italy and Sicily. It is a Mediterranean with a more equable climate, warmer winters and cooler summers, than the North Mediterranean shore can offer; it is an Italy whose mountains and valleys give almost every variety of elevation and temperature.

But it is our commercial Mediterranean. The time is not distant when this corner of the United States will produce in abundance, and year after year without failure, all the fruits and nuts which for a thousand years the civilized world of Europe has looked to the Mediterranean to supply. We shall not need any more to send over the Atlantic for raisins, English walnuts, almonds, figs, olives, prunes, oranges, lemons, limes, and a variety of other things which we know[Pg 19] commercially as Mediterranean products. We have all this luxury and wealth at our doors, within our limits. The orange and the lemon we shall still bring from many places; the date and the pineapple and the banana will never grow here except as illustrations of the climate, but it is difficult to name any fruit of the temperate and semi-tropic zones that Southern California cannot be relied on to produce, from the guava to the peach.

It will need further experiment to determine what are the more profitable products of this soil, and it will take longer experience to cultivate them and send them to market in perfection. The pomegranate and the apple thrive side by side, but the apple is not good here unless it is grown at an elevation where frost is certain and occasional snow may be expected. There is no longer any doubt about the peach, the nectarine, the pear, the grape, the orange, the lemon, the apricot, and so on; but I believe that the greatest profit will be in the products that cannot be grown elsewhere in the United States—the products to which we have long given the name of Mediterranean—the olive, the fig, the raisin, the hard and soft shell almond, and the walnut. The orange will of course be a staple, and constantly improve its reputation as better varieties are raised, and the right amount of irrigation to produce the finest and sweetest is ascertained.

It is still a wonder that a land in which there was no indigenous product of value, or to which cultivation could give value, should be so hospitable to every sort of tree, shrub, root, grain, and flower that can be brought here from any zone and temperature, and that many of these foreigners to the soil grow here[Pg 20] with a vigor and productiveness surpassing those in their native land. This bewildering adaptability has misled many into unprofitable experiments, and the very rapidity of growth has been a disadvantage. The land has been advertised by its monstrous vegetable productions, which are not fit to eat, and but testify to the fertility of the soil; and the reputation of its fruits, both deciduous and citrus, has suffered by specimens sent to Eastern markets whose sole recommendation was size. Even in the vineyards and orange orchards quality has been sacrificed to quantity. Nature here responds generously to every encouragement, but it cannot be forced without taking its revenge in the return of inferior quality. It is just as true of Southern California as of any other land, that hard work and sagacity and experience are necessary to successful horticulture and agriculture, but it is undeniably true that the same amount of well-directed industry upon a much smaller area of land will produce more return than in almost any other section of the United States. Sensible people do not any longer pay much attention to those tempting little arithmetical sums by which it is demonstrated that paying so much for ten acres of barren land, and so much for planting it with vines or oranges, the income in three years will be a competence to the investor and his family. People do not spend much time now in gaping over abnormal vegetables, or trying to convince themselves that wines of every known variety and flavor can be produced within the limits of one flat and well-watered field. Few now expect to make a fortune by cutting arid land up into twenty-feet lots, but notwithstanding the extravagance of recent speculation, the value of arable land has steadily appreciated, and is not likely to recede, for the return from it, either in fruits, vegetables, or grain, is demonstrated to be beyond the experience of farming elsewhere.[Pg 21]

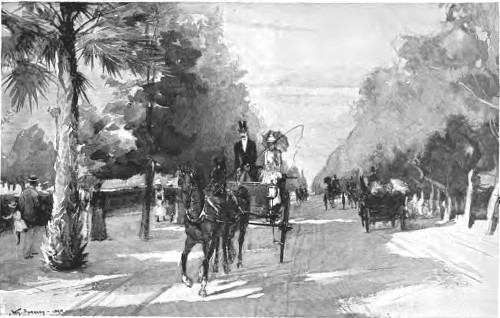

MAGNOLIA AVENUE, RIVERSIDE.

MAGNOLIA AVENUE, RIVERSIDE.

Land cannot be called dear at one hundred or one thousand dollars an acre if the annual return from it is fifty or five hundred dollars. The climate is most agreeable the year through. There are no unpleasant months, and few unpleasant days. The eucalyptus grows so fast that the trimmings from the trees of a small grove or highway avenue will in four or five years furnish a family with its firewood. The strong, fattening alfalfa gives three, four, five, and even six harvests a year. Nature needs little rest, and, with the encouragement of water and fertilizers, apparently none. But all this prodigality and easiness of life detracts a little from ambition. The lesson has been slowly learned, but it is now pretty well conned, that hard work is as necessary here as elsewhere to thrift and independence. The difference between this and many other parts of our land is that nature seems to work with a man, and not against him.

Southern California has rapidly passed through varied experiences, and has not yet had a fair chance to show the world what it is. It had its period of romance, of pastoral life, of lawless adventure, of crazy speculation, all within a hundred years, and it is just now entering upon its period of solid, civilized development. A certain light of romance is cast upon this coast by the Spanish voyagers of the sixteenth century, but its history begins with the establishment of the chain of Franciscan missions, the first of which was founded by the great Father Junipero Serra at San Diego in 1769. The fathers brought with them the vine and the olive, reduced the savage Indians to industrial pursuits, and opened the way for that ranchero and adobe civilization which, down to the coming of the American, in about 1840, made in this region the most picturesque life that our continent has ever seen. Following this is a period of desperado adventure and revolution, of pioneer State-building; and then the advent of the restless, the cranky, the invalid, the fanatic, from every other State in the Union. The first experimenters in making homes seem to have fancied that they had come to a ready-made elysium—the idle man's heaven. They seem to[Pg 25] have brought with them little knowledge of agriculture or horticulture, were ignorant of the conditions of success in this soil and climate, and left behind the good industrial maxims of the East. The result was a period of chance experiment, one in which extravagant expectation and boasting to some extent took the place of industry. The imagination was heated by the novelty of such varied and rapid productiveness. Men's minds were inflamed by the apparently limitless possibilities. The invalid and the speculator thronged the transcontinental roads leading thither. In this condition the frenzy of 1886-87 was inevitable. I saw something of it in the winter of 1887. The scenes then daily and commonplace now read like the wildest freaks of the imagination.

The bubble collapsed as suddenly as it expanded. Many were ruined, and left the country. More were merely ruined in their great expectations. The speculation was in town lots. When it subsided it left the climate as it was, the fertility as it was, and the value of arable land not reduced. Marvellous as the boom was, I think the present recuperation is still more wonderful. In 1890, to be sure, I miss the bustle of the cities, and the creation of towns in a week under the hammer of the auctioneer. But in all the cities, and most of the villages, there has been growth in substantial buildings, and in the necessities of civic life—good sewerage, water supply, and general organization; while the country, as the acreage of vines and oranges, wheat and barley, grain and corn, and the shipments by rail testify, has improved more than at any other period, and commerce is beginning to feel the impulse of a genuine prosperity,[Pg 26] based upon the intelligent cultivation of the ground. School-houses have multiplied; libraries have been founded; many "boom" hotels, built in order to sell city lots in the sage-brush, have been turned into schools and colleges.

There is immense rivalry between different sections. Every Californian thinks that the spot where his house stands enjoys the best climate and is the most fertile in the world; and while you are with him you think he is justified in his opinion; for this rivalry is generally a wholesome one, backed by industry. I do not mean to say that the habit of tall talk is altogether lost. Whatever one sees he is asked to believe is the largest and best in the world. The gentleman of the whip who showed us some of the finest places in Los Angeles—places that in their wealth of flowers and semi-tropical gardens would rouse the enthusiasm of the most jaded traveller—was asked whether there were any finer in the city. "Finer? Hundreds of them;" and then, meditatively and regretfully, "I should not dare to show you the best." The semi-ecclesiastical custodian of the old adobe mission of San Gabriel explained to us the twenty portraits of apostles on the walls, all done by Murillo. As they had got out of repair, he had them all repainted by the best artist. "That one," he said, simply, "cost ten dollars. It often costs more to repaint a picture than to buy an original."

The temporary evils in the train of the "boom" are fast disappearing. I was told that I should find the country stagnant. Trade, it is true, is only slowly coming in, real-estate deals are sleeping, but in all avenues of solid prosperity and productiveness the country is the reverse of stagnant. Another misapprehension this visit is correcting. I was told not to visit Southern California at this season on account of the heat. But I have no experience of a more delightful summer climate than this, especially on or near the coast.[Pg 27]

AVENUE LOS ANGELES.

AVENUE LOS ANGELES.

In secluded valleys in the interior the thermometer rises in the daytime to 85°, 90°, and occasionally 100°, but I have found no place in them where there was not daily a refreshing breeze from the ocean, where the dryness of the air did not make the heat seem much less than it was, and where the nights were not agreeably cool. My belief is that the summer climate of Southern California is as desirable for pleasure-seekers, for invalids, for workmen, as its winter climate. It seems to me that a coast temperature 60° to 75°, stimulating, without harshness or dampness, is about the perfection of summer weather. It should be said, however, that there are secluded valleys which become very hot in the daytime in midsummer, and intolerably dusty. The dust is the great annoyance everywhere. It gives the whole landscape an ashy tint, like some of our Eastern fields and way-sides in a dry August. The verdure and the wild flowers of the rainy season disappear entirely. There is, however, some picturesque compensation for this dust and lack of green. The mountains and hills and great plains take on wonderful hues of brown, yellow, and red.

I write this paragraph in a high chamber in the Hotel del Coronado, on the great and fertile beach in front of San Diego. It is the 2d of June. Looking southward, I see the great expanse of the Pacific[Pg 30] Ocean, sparkling in the sun as blue as the waters at Amalfi. A low surf beats along the miles and miles of white sand continually, with the impetus of far-off seas and trade-winds, as it has beaten for thousands of years, with one unending roar and swish, and occasional shocks of sound as if of distant thunder on the shore. Yonder, to the right, Point Loma stretches its sharp and rocky promontory into the ocean, purple in the sun, bearing a light-house on its highest elevation. From this signal, bending in a perfect crescent, with a silver rim, the shore sweeps around twenty-five miles to another promontory running down beyond Tia Juana to the Point of Rocks, in Mexican territory. Directly in front—they say eighteen miles away, I think five sometimes, and sometimes a hundred—lie the islands of Coronado, named, I suppose, from the old Spanish adventurer Vasques de Coronado, huge bulks of beautiful red sandstone, uninhabited and barren, becalmed there in the changing blue of sky and sea, like enormous mastless galleons, like degraded icebergs, like Capri and Ischia. They say that they are stationary. I only know that when I walk along the shore towards Point Loma they seem to follow, until they lie opposite the harbor entrance, which is close by the promontory; and that when I return, they recede and go away towards Mexico, to which they belong. Sometimes, as seen from the beach, owing to the difference in the humidity of the strata of air over the ocean, they seem smaller at the bottom than at the top. Occasionally they come quite near, as do the sea-lions and the gulls, and again they almost fade out of the horizon in a violet light. This morning they stand away, and the fleet of white-sailed fishing-boats from the Portuguese hamlet of La Playa, within the harbor entrance, which is dancing off Point Loma, will have a long sail if they pursue the barracuda to those shadowy rocks.[Pg 31]

IN THE GARDEN AT SANTA BARBARA MISSION.

IN THE GARDEN AT SANTA BARBARA MISSION.

We crossed the bay the other day, and drove up a wild road to the height of the promontory, and along its narrow ridge to the light-house. This site commands one of the most remarkable views in the accessible civilized world, one of the three or four really great prospects which the traveller can recall, astonishing in its immensity, interesting in its peculiar details. The general features are the great ocean, blue, flecked with sparkling, breaking wavelets, and the wide, curving coast-line, rising into mesas, foot-hills, ranges on ranges of mountains, the faintly seen snow-peaks of San Bernardino and San Jacinto to the Cuyamaca and the flat top of Table Mountain in Mexico. Directly under us on one side are the fields of kelp, where the whales come to feed in winter; and on the other is a point of sand on Coronado Beach, where a flock of pelicans have assembled after their day's fishing, in which occupation they are the rivals of the Portuguese. The perfect crescent of the ocean beach is seen, the singular formation of North and South Coronado Beach, the entrance to the harbor along Point Loma, and the spacious inner bay, on which lie San Diego and National City, with lowlands and heights outside sprinkled with houses, gardens, orchards, and vineyards. The near hills about this harbor are varied in form and poetic in color, one of them, the conical San Miguel, constantly recalling Vesuvius. Indeed, the near view, in[Pg 34] color, vegetation, and forms of hills and extent of arable land, suggests that of Naples, though on analysis it does not resemble it. If San Diego had half a million of people it would be more like it; but the Naples view is limited, while this stretches away to the great mountains that overlook the Colorado Desert. It is certainly one of the loveliest prospects in the world, and worth long travel to see.

Standing upon this point of view, I am reminded again of the striking contrasts and contiguous different climates on the coast. In the north, of course not visible from here, is Mount Whitney, on the borders of Inyo County and of the State of Nevada, 15,086 feet above the sea, the highest peak in the United States, excluding Alaska. South of it is Grayback, in the San Bernardino range, 11,000 feet in altitude, the highest point above its base in the United States. While south of that is the depression in the Colorado Desert in San Diego County, about three hundred feet below the level of the Pacific Ocean, the lowest land in the United States. These three exceptional points can be said to be almost in sight of each other.[Pg 35]

SCENE AT PASADENA.

SCENE AT PASADENA.

I have insisted so much upon the Mediterranean character of this region that it is necessary to emphasize the contrasts also. Reserving details and comments on different localities as to the commercial value of products and climatic conditions, I will make some general observations. I am convinced that the fig can not only be grown here in sufficient quantity to supply our markets, but of the best quality. The same may be said of the English walnut. This clean and handsome tree thrives wonderfully in large areas, and has no enemies. The olive culture is in its infancy, but I have never tasted better oil than that produced at Santa Barbara and on San Diego Bay. Specimens of the pickled olive are delicious, and when the best varieties are generally grown, and the best method of curing is adopted, it will be in great demand, not as a mere relish, but as food. The raisin is produced in all the valleys of Southern California, and in great quantities in the hot valley of San Joaquin, beyond the Sierra Madre range. The best Malaga raisins, which have the reputation of being the best in the world, may never come to our market, but I have never eaten a better raisin for size, flavor, and thinness of skin than those raised in the El Cajon Valley, which is watered by the great flume which taps a reservoir in the Cuyamaca Mountains, and supplies San Diego. But the quality of the raisin in California will be improved by experience in cultivation and handling.

The contrast with the Mediterranean region—I refer to the western basin—is in climate. There is hardly any point along the French and Italian coast that is not subject to great and sudden changes, caused by the north wind, which has many names, or in the extreme southern peninsula and islands by the sirocco. There are few points that are not reached by malaria, and in many resorts—and some of them most sunny and agreeable to the invalid—the deadliest fevers always lie in wait. There is great contrast between summer and winter, and exceeding variability in the same month. This variability is the parent of many diseases of the lungs, the bowels, and the liver. It is demonstrated now by long-continued observations[Pg 38] that dampness and cold are not so inimical to health as variability.

The Southern California climate is an anomaly. It has been the subject of a good deal of wonder and a good deal of boasting, but it is worthy of more scientific study than it has yet received. Its distinguishing feature I take to be its equability. The temperature the year through is lower than I had supposed, and the contrast is not great between the summer and the winter months. The same clothing is appropriate, speaking generally, for the whole year. In all seasons, including the rainy days of the winter months, sunshine is the rule. The variation of temperature between day and night is considerable, but if the new-comer exercises a little care, he will not be unpleasantly affected by it. There are coast fogs, but these are not chilling and raw. Why it is that with the hydrometer showing a considerable humidity in the air the general effect of the climate is that of dryness, scientists must explain. The constant exchange of desert airs with the ocean air may account for the anomaly, and the actual dryness of the soil, even on the coast, is put forward as another explanation. Those who come from heated rooms on the Atlantic may find the winters cooler than they expect, and those used to the heated terms of the Mississippi Valley and the East will be surprised at the cool and salubrious summers. A land without high winds or thunder-storms may fairly be said to have a unique climate.[Pg 39]

LIVE-OAK NEAR LOS ANGELES.

LIVE-OAK NEAR LOS ANGELES.

I suppose it is the equability and not conditions of dampness or dryness that renders this region so remarkably exempt from epidemics and endemic diseases. The diseases of children prevalent elsewhere are unknown here; they cut their teeth without risk, and cholera infantum never visits them. Diseases of the bowels are practically unknown. There is no malaria, whatever that may be, and consequently an absence of those various fevers and other disorders which are attributed to malarial conditions. Renal diseases are also wanting; disorders of the liver and kidneys, and Bright's disease, gout, and rheumatism, are not native. The climate in its effect is stimulating, but at the same time soothing to the nerves, so that if "nervous prostration" is wanted, it must[Pg 40] be brought here, and cannot be relied on to continue long. These facts are derived from medical practice with the native Indian and Mexican population. Dr. Remondino, to whom I have before referred, has made the subject a study for eighteen years, and later I shall offer some of the results of his observations upon longevity. It is beyond my province to venture any suggestion upon the effect of the climate upon deep-seated diseases, especially of the respiratory organs, of invalids who come here for health. I only know that we meet daily and constantly so many persons in fair health who say that it is impossible for them to live elsewhere that the impression is produced that a considerable proportion of the immigrant population was invalid. There are, however, two suggestions that should be made. Care is needed in acclimation to a climate that differs from any previous experience; and the locality that will suit any invalid can only be determined by personal experience. If the coast does not suit him, he may be benefited in a protected valley, or he may be improved on the foot-hills, or on an elevated mesa, or on a high mountain elevation.

One thing may be regarded as settled. Whatever the sensibility or the peculiarity of invalidism, the equable climate is exceedingly favorable to the smooth working of the great organic functions of respiration, digestion, and circulation.

It is a pity to give this chapter a medical tone. One need not be an invalid to come here and appreciate the graciousness of the air; the color of the landscape, which is wanting in our Northern clime; the constant procession of flowers the year through;[Pg 41] the purple hills stretching into the sea; the hundreds of hamlets, with picturesque homes overgrown with roses and geranium and heliotrope, in the midst of orange orchards and of palms and magnolias, in sight of the snow-peaks of the giant mountain ranges which shut in this land of marvellous beauty.

California is the land of the Pine and the Palm. The tree of the Sierras, native, vigorous, gigantic, and the tree of the Desert, exotic, supple, poetic, both flourish within the nine degrees of latitude. These two, the widely separated lovers of Heine's song, symbolize the capacities of the State, and although the sugar-pine is indigenous, and the date-palm, which will never be more than an ornament in this hospitable soil, was planted by the Franciscan Fathers, who established a chain of missions from San Diego to Monterey over a century ago, they should both be the distinction of one commonwealth, which, in its seven hundred miles of indented sea-coast, can boast the climates of all countries and the products of all zones.

If this State of mountains and valleys were divided by an east and west line, following the general course of the Sierra Madre range, and cutting off the eight lower counties, I suppose there would be conceit enough in either section to maintain that it only is the Paradise of the earth, but both are necessary to make the unique and contradictory California which fascinates and bewilders the traveller. He is told that the inhabitants of San Francisco go away from the draught of the Golden Gate in the summer to get[Pg 43] warm, and yet the earliest luscious cherries and apricots which he finds in the far south market of San Diego come from the Northern Santa Clara Valley. The truth would seem to be that in an hour's ride in any part of the State one can change his climate totally at any time of the year, and this not merely by changing his elevation, but by getting in or out of the range of the sea or the desert currents of air which follow the valleys.

To recommend to any one a winter climate is far from the writer's thought. No two persons agree on what is desirable for a winter residence, and the inclination of the same person varies with his state of health. I can only attempt to give some idea of what is called the winter months in Southern California, to which my observations mainly apply. The individual who comes here under the mistaken notion that climate ever does anything more than give nature a better chance, may speedily or more tardily need the service of an undertaker; and the invalid whose powers are responsive to kindly influences may live so long, being unable to get away, that life will be a burden to him. The person in ordinary health will find very little that is hostile to the orderly organic processes. In order to appreciate the winter climate of Southern California one should stay here the year through, and select the days that suit his idea of winter from any of the months. From the fact that the greatest humidity is in the summer and the least in the winter months, he may wear an overcoat in July in a temperature, according to the thermometer, which in January would render the overcoat unnecessary. It is dampness that causes both cold and heat to be most[Pg 44] felt. The lowest temperatures, in Southern California generally, are caused only by the extreme dryness of the air; in the long nights of December and January there is a more rapid and longer continued radiation of heat. It must be a dry and clear night that will send the temperature down to thirty-four degrees. But the effect of the sun upon this air is instantaneous, and the cold morning is followed at once by a warm forenoon; the difference between the average heat of July and the average cold of January, measured by the thermometer, is not great in the valleys, foot-hills, and on the coast. Five points give this result of average for January and July respectively: Santa Barbara, 52°, 66°; San Bernardino, 51°, 70°; Pomona, 52°, 68°; Los Angeles, 52°, 67°; San Diego, 53°, 66°. The day in the winter months is warmer in the interior and the nights are cooler than on the coast, as shown by the following figures for January: 7 a.m., Los Angeles, 46.5°; San Diego, 47.5°; 3 p.m., Los Angeles, 65.2°; San Diego, 60.9°. In the summer the difference is greater. In June I saw the thermometer reach 103° in Los Angeles when it was only 79° in San Diego. But I have seen the weather unendurable in New York with a temperature of 85°, while this dry heat of 103° was not oppressive. The extraordinary equanimity of the coast climate (certainly the driest marine climate in my experience) will be evident from the average mean for each month, from records of sixteen years, ending in 1877, taken at San Diego, giving each month in order, beginning with January: 53.5°, 54.7°, 56.0°, 58.2°, 60.2°, 64.6°, 67.1°, 69.0°, 66.7°, 62.9°, 58.1°, 56.0°. In the year 1877 the mean temperature at 3 p.m. at San Diego was as follows,[Pg 45] beginning with January: 60.9°, 57.7°, 62.4°, 63.3°, 66.3°, 68.5°, 69.6°, 69.6°, 69.5°, 69.6°, 64.4°, 60.5°. For the four months of July, August, September, and October there was hardly a shade of difference at 3 p.m. The striking fact in all the records I have seen is that the difference of temperature in the daytime between summer and winter is very small, the great difference being from midnight to just before sunrise, and this latter difference is greater inland than on the coast. There are, of course, frost and ice in the mountains, but the frost that comes occasionally in the low inland valleys is of very brief duration in the morning hour, and rarely continues long enough to have a serious effect upon vegetation.

In considering the matter of temperature, the rule for vegetation and for invalids will not be the same. A spot in which delicate flowers in Southern California bloom the year round may be too cool for many invalids. It must not be forgotten that the general temperature here is lower than that to which most Eastern people are accustomed. They are used to living all winter in overheated houses, and to protracted heated terms rendered worse by humidity in the summer. The dry, low temperature of the California winter, notwithstanding its perpetual sunshine, may seem, therefore, wanting to them in direct warmth. It may take a year or two to acclimate them to this more equable and more refreshing temperature.

Neither on the coast nor in the foot-hills will the invalid find the climate of the Riviera or of Tangier—not the tramontane wind of the former, nor the absolutely genial but somewhat enervating climate of[Pg 46] the latter. But it must be borne in mind that in this, our Mediterranean, the seeker for health or pleasure can find almost any climate (except the very cold or the very hot), down to the minutest subdivision. He may try the dry marine climate of the coast, or the temperature of the fruit lands and gardens from San Bernardino to Los Angeles, or he may climb to any altitude that suits him in the Sierra Madre or the San Jacinto ranges. The difference may be all-important to him between a valley and a mesa which is not a hundred feet higher; nay, between a valley and the slope of a foot-hill, with a shifting of not more than fifty feet elevation, the change may be as marked for him as it is for the most sensitive young fruit-tree. It is undeniable, notwithstanding these encouraging "averages," that cold snaps, though rare, do come occasionally, just as in summer there will occur one or two or three continued days of intense heat. And in the summer in some localities—it happened in June, 1890, in the Santiago hills in Orange County—the desert sirocco, blowing over the Colorado furnace, makes life just about unendurable for days at a time. Yet with this dry heat sunstroke is never experienced, and the diseases of the bowels usually accompanying hot weather elsewhere are unknown. The experienced traveller who encounters unpleasant weather, heat that he does not expect, cold that he did not provide for, or dust that deprives him of his last atom of good-humor, and is told that it is "exceptional," knows exactly what that word means. He is familiar with the "exceptional" the world over, and he feels a sort of compassion for the inhabitants who have not yet[Pg 47] learned the adage, "Good wine needs no bush." Even those who have bought more land than they can pay for can afford to tell the truth.

The rainy season in Southern California, which may open with a shower or two in October, but does not set in till late in November, or till December, and is over in April, is not at all a period of cloudy weather or continuous rainfall. On the contrary, bright warm days and brilliant sunshine are the rule. The rain is most likely to fall in the night. There may be a day of rain, or several days that are overcast with distributed rain, but the showers are soon over, and the sky clears. Yet winters vary greatly in this respect, the rainfall being much greater in some than in others. In 1890 there was rain beyond the average, and even on the equable beach of Coronada there were some weeks of weather that from the California point of view were very unpleasant. It was unpleasant by local comparison, but it was not damp and chilly, like a protracted period of falling weather on the Atlantic. The rain comes with a southerly wind, caused by a disturbance far north, and with the resumption of the prevailing westerly winds it suddenly ceases, the air clears, and neither before nor after it is the atmosphere "steamy" or enervating. The average annual rainfall of the Pacific coast diminishes by regular gradation from point to point all the way from Puget Sound to the Mexican boundary. At Neah Bay it is 111 inches, and it steadily lessens down to Santa Cruz, 25.24; Monterey, 11.42; Point Conception, 12.21; San Diego, 11.01. There is fog on the coast in every month, but this diminishes, like the rainfall, from north to south. I have encountered it[Pg 48] in both February and June. In the south it is apt to be most persistent in April and May, when for three or four days together there will be a fine mist, which any one but a Scotchman would call rain. Usually, however, the fog-bank will roll in during the night, and disappear by ten o'clock in the morning. There is no wet season properly so called, and consequently few days in the winter months when it is not agreeable to be out-of-doors, perhaps no day when one may not walk or drive during some part of it. Yet as to precipitation or temperature it is impossible to strike any general average for Southern California. In 1883-84 San Diego had 25.77 inches of rain, and Los Angeles (fifteen miles inland) had 38.22. The annual average at Los Angeles is 17.64; but in 1876-77 the total at San Diego was only 3.75, and at Los Angeles only 5.28. Yet elevation and distance from the coast do not always determine the rainfall. The yearly mean rainfall at Julian, in the San Jacinto range, at an elevation of 4500 feet, is 37.74; observations at Riverside, 1050 feet above the sea, give an average of 9.37.

It is probably impossible to give an Eastern man a just idea of the winter of Southern California. Accustomed to extremes, he may expect too much. He wants a violent change. If he quits the snow, the slush, the leaden skies, the alternate sleet and cold rain of New England, he would like the tropical heat, the languor, the color of Martinique. He will not find them here. He comes instead into a strictly temperate region; and even when he arrives, his eyes deceive him. He sees the orange ripening in its dark foliage, the long lines of the eucalyptus, the feathery pepper-tree, the magnolia, the English walnut, the[Pg 49] black live-oak, the fan-palm, in all the vigor of June; everywhere beds of flowers of every hue and of every country blazing in the bright sunlight—the heliotrope, the geranium, the rare hot-house roses overrunning the hedges of cypress, and the scarlet passion-vine climbing to the roof-tree of the cottages; in the vineyard or the orchard the horticulturist is following the cultivator in his shirt-sleeves; he hears running water, the song of birds, the scent of flowers is in the air, and he cannot understand why he needs winter clothing, why he is always seeking the sun, why he wants a fire at night. It is a fraud, he says, all this visible display of summer, and of an almost tropical summer at that; it is really a cold country. It is incongruous that he should be looking at a date-palm in his overcoat, and he is puzzled that a thermometrical heat that should enervate him elsewhere, stimulates him here. The green, brilliant, vigorous vegetation, the perpetual sunshine, deceive him; he is careless about the difference of shade and sun, he gets into a draught, and takes cold. Accustomed to extremes of temperature and artificial heat, I think for most people the first winter here is a disappointment. I was told by a physician who had eighteen years' experience of the climate that in his first winter he thought he had never seen a people so insensitive to cold as the San Diegans, who seemed not to require warmth. And all this time the trees are growing like asparagus, the most delicate flowers are in perpetual bloom, the annual crops are most lusty. I fancy that the soil is always warm. The temperature is truly moderate. The records for a number of years show that the mid-day temperature of clear days in winter is from 60° to 70° on the coast,[Pg 50] from 65° to 80° in the interior, while that of rainy days is about 60° by the sea and inland. Mr. Van Dyke says that the lowest mid-day temperature recorded at the United States signal station at San Diego during eight years is 51°. This occurred but once. In those eight years there were but twenty-one days when the mid-day temperature was not above 55°. In all that time there were but six days when the mercury fell below 36° at any time in the night; and but two when it fell to 32°, the lowest point ever reached there. On one of these two last-named days it went to 51° at noon, and on the other to 56°. This was the great "cold snap" of December, 1879.

It goes without saying that this sort of climate would suit any one in ordinary health, inviting and stimulating to constant out-of-door exercise, and that it would be equally favorable to that general breakdown of the system which has the name of nervous prostration. The effect upon diseases of the respiratory organs can only be determined by individual experience. The government has lately been sending soldiers who have consumption from various stations in the United States to San Diego for treatment. This experiment will furnish interesting data. Within a period covering a little over two years, Dr. Huntington, the post surgeon, has had fifteen cases sent to him. Three of these patients had tubercular consumption; twelve had consumption induced by attacks of pneumonia. One of the tubercular patients died within a month after his arrival; the second lived eight months; the third was discharged cured, left the army, and contracted malaria elsewhere, of which he died. The remaining twelve were discharged practically[Pg 51] cured of consumption, but two of them subsequently died. It is exceedingly common to meet persons of all ages and both sexes in Southern California who came invalided by disease of the lungs or throat, who have every promise of fair health here, but who dare not leave this climate. The testimony is convincing of the good effect of the climate upon all children, upon women generally, and of its rejuvenating effect upon men and women of advanced years.

In regard to the effect of climate upon health and longevity, Dr. Remondino quotes old Hufeland that "uniformity in the state of the atmosphere, particularly in regard to heat, cold, gravity, and lightness, contributes in a very considerable degree to the duration of life. Countries, therefore, where great and sudden varieties in the barometer and the thermometer are usual cannot be favorable to longevity. Such countries may be healthy, and many men may become old in them, but they will not attain to a great age, for all rapid variations are so many internal mutations, and these occasion an astonishing consumption both of the forces and the organs." Hufeland thought a marine climate most favorable to longevity. He describes, and perhaps we may say prophesied, a region he had never known, where the conditions and combinations were most favorable to old age, which is epitomized by Dr. Remondino: "where the latitude gives warmth and the sea or ocean tempering winds, where the soil is warm and dry and the sun is also bright and warm, where uninterrupted bright clear weather and a moderate temperature are the rule, where extremes neither of heat nor cold are to be found, where nothing may interfere with the exercise of the aged, and where the actual results and cases of longevity will bear testimony as to the efficacy of all its climatic conditions being favorable to a long and comfortable existence."[Pg 53]

MIDWINTER, PASADENA.

MIDWINTER, PASADENA.

In an unpublished paper Dr. Remondino comments on the extraordinary endurance of animals and men in the California climate, and cites many cases of uncommon longevity in natives. In reading the accounts of early days in California I am struck with the endurance of hardship, exposure, and wounds by the natives and the adventurers, the rancheros, horsemen, herdsmen, the descendants of soldiers and the Indians, their insensibility to fatigue, and their agility and strength. This is ascribed to the climate; and what is true of man is true of the native horse. His only rival in strength, endurance, speed, and intelligence is the Arabian. It was long supposed that this was racial, and that but for the smallness of the size of the native horse, crossing with it would improve the breed of the Eastern and Kentucky racers. But there was reluctance to cross the finely proportioned Eastern horse with his diminutive Western brother. The importation and breeding of thoroughbreds on this coast has led to the discovery that the desirable qualities of the California horse were not racial but climatic. The Eastern horse has been found to improve in size, compactness of muscle, in strength of limb, in wind, with a marked increase in power of endurance. The traveller here notices the fine horses and their excellent condition, and the power and endurance of those that have considerable age. The records made on Eastern race-courses by horses from California breeding farms have already attracted attention. It is also remarked that the Eastern horse is usually improved greatly by[Pg 56] a sojourn of a season or two on this coast, and the plan of bringing Eastern race-horses here for the winter is already adopted.

Man, it is asserted by our authority, is as much benefited as the horse by a change to this climate. The new-comer may have certain unpleasant sensations in coming here from different altitudes and conditions, but he will soon be conscious of better being, of increased power in all the functions of life, more natural and recuperative sleep, and an accession of vitality and endurance. Dr. Remondino also testifies that it occasionally happens in this rejuvenation that families which have seemed to have reached their limit at the East are increased after residence here.

The early inhabitants of Southern California, according to the statement of Mr. H. H. Bancroft and other reports, were found to be living in Spartan conditions as to temperance and training, and in a highly moral condition, in consequence of which they had uncommon physical endurance and contempt for luxury. This training in abstinence and hardship, with temperance in diet, combined with the climate to produce the astonishing longevity to be found here. Contrary to the customs of most other tribes of Indians, their aged were the care of the community. Dr. W. A. Winder, of San Diego, is quoted as saying that in a visit to El Cajon Valley some thirty years ago he was taken to a house in which the aged persons were cared for. There were half a dozen who had reached an extreme age. Some were unable to move, their bony frame being seemingly anchylosed. They were old, wrinkled, and blear-eyed; their skin was hanging in leathery folds about their withered limbs; some had hair as white as snow, and had seen some seven-score of years; others, still able to crawl, but so aged as to be unable to stand, went slowly about on their hands and knees, their limbs being attenuated and withered. The organs of special sense had in many nearly lost all activity some generations back. Some had lost the use of their limbs for more than a decade or a generation; but the organs of life and the "great sympathetic" still kept up their automatic functions, not recognizing the fact, and surprisingly indifferent to it, that the rest of the body had ceased to be of any use a generation or more in the past. And it is remarked that "these thoracic and abdominal organs and their physiological action being kept alive and active, as it were, against time, and the silent and unconscious functional activity of the great sympathetic and its ganglia, show a tenacity of the animal tissues to hold on to life that is phenomenal."[Pg 57]

A TYPICAL GARDEN, NEAR SANTA ANA.

A TYPICAL GARDEN, NEAR SANTA ANA.

I have no space to enter upon the nature of the testimony upon which the age of certain Indians hereafter referred to is based. It is such as to satisfy Dr. Remondino, Dr. Edward Palmer, long connected with the Agricultural Department of the Smithsonian Institution, and Father A. D. Ubach, who has religious charge of the Indians in this region. These Indians were not migratory; they lived within certain limits, and were known to each other. The missions established by the Franciscan friars were built with the assistance of the Indians. The friars have handed down by word of mouth many details in regard to their early missions; others are found in the mission records, such as carefully kept records of family events—births, marriages, and deaths. And there is the testimony of[Pg 60] the Indians regarding each other. Father Ubach has known a number who were employed at the building of the mission of San Diego (1769-71), a century before he took charge of this mission. These men had been engaged in carrying timber from the mountains or in making brick, and many of them were living within the last twenty years. There are persons still living at the Indian village of Capitan Grande whose ages he estimates at over one hundred and thirty years. Since the advent of civilization the abstemious habits and Spartan virtues of these Indians have been impaired, and their care for the aged has relaxed.

Dr. Palmer has a photograph (which I have seen) of a squaw whom he estimates to be 126 years old. When he visited her he saw her put six watermelons in a blanket, tie it up, and carry it on her back for two miles. He is familiar with Indian customs and history, and a careful cross-examination convinced him that her information of old customs was not obtained by tradition. She was conversant with tribal habits she had seen practised, such as the cremation of the dead, which the mission fathers had compelled the Indians to relinquish. She had seen the Indians punished by the fathers with floggings for persisting in the practice of cremation.

At the mission of San Tomas, in Lower California, is still living an Indian (a photograph of whom Dr. Remondino shows), bent and wrinkled, whose age is computed at 140 years. Although blind and naked, he is still active, and daily goes down the beach and along the beds of the creeks in search of drift-wood, making it his daily task to gather and carry to camp a fagot of wood.[Pg 61]

OLD ADOBE HOUSE, POMONA.

OLD ADOBE HOUSE, POMONA.

Another instance I give in Dr. Remondino's words: "Philip Crossthwaite, who has lived here since 1843, has an old man on his ranch who mounts his horse and rides about daily, who was a grown man breaking horses for the mission fathers when Don Antonio Serrano was an infant. Don Antonio I know quite well, having attended him through a serious illness some sixteen years ago. Although now at the advanced age of ninety-three, he is as erect as a pine, and he rides[Pg 62] his horse with his usual vigor and grace. He is thin and spare and very tall, and those who knew him fifty years or more remember him as the most skilful horseman in the neighborhood of San Diego. And yet, as fabulous as it may seem, the man who danced this Don Antonio on his knee when he was an infant is not only still alive, but is active enough to mount his horse and canter about the country. Some years ago I attended an elderly gentleman, since dead, who knew this man as a full-grown man when he and Don Serrano were play-children together. From a conversation with Father Ubach I learned that the man's age is perfectly authenticated to be beyond one hundred and eighteen years."

In the many instances given of extreme old age in this region the habits of these Indians have been those of strict temperance and abstemiousness, and their long life in an equable climate is due to extreme simplicity of diet. In many cases of extreme age the diet has consisted simply of acorns, flour, and water. It is asserted that the climate itself induces temperance in drink and abstemiousness in diet. In his estimate of the climate as a factor of longevity, Dr. Remondino says that it is only necessary to look at the causes of death, and the ages most subject to attack, to understand that the less of these causes that are present the greater are the chances of man to reach great age. "Add to these reflections that you run no gantlet of diseases to undermine or deteriorate the organism; that in this climate childhood finds an escape from those diseases which are the terror of mothers, and against which physicians are helpless, as we have here none of those affections of the first three years of life[Pg 63] so prevalent during the summer months in the East and the rest of the United States. Then, again, the chance of gastric or intestinal disease is almost incredibly small. This immunity extends through every age of life. Hepatic and kindred diseases are unknown; of lung affections there is no land that can boast of like exemption. Be it the equability of the temperature or the aseptic condition of the atmosphere, the free sweep of winds or the absence of disease germs, or what else it may be ascribed to, one thing is certain, that there is no pneumonia, bronchitis, or pleurisy lying in wait for either the infant or the aged."

FAN-PALM, FERNANDO ST. LOS ANGELES.

FAN-PALM, FERNANDO ST. LOS ANGELES.

The importance of this subject must excuse the space I have given to it. It is evident from this testimony that here are climatic conditions novel and worthy of the most patient scientific investigation. Their effect upon hereditary tendencies and upon persons coming here with hereditary diseases will be studied. Three years ago there was in some localities a visitation of small-pox imported from Mexico. At that time there were cases of pneumonia. Whether these were incident to carelessness in vaccination, or were caused by local unsanitary conditions, I do not know. It is not to be expected that unsanitary conditions will not produce disease here as elsewhere. It cannot be too strongly insisted that this is a climate that the new-comer must get used to, and that he cannot safely neglect the ordinary precautions. The difference between shade and sun is strikingly marked, and he must not be deceived into imprudence by the prevailing sunshine or the general equability.

After all these averages and statistics, and not considering now the chances of the speculator, the farmer, the fruit-raiser, or the invalid, is Southern California a particularly agreeable winter residence? The question deserves a candid answer, for it is of the last importance to the people of the United States to know the truth—to know whether they have accessible by rail a region free from winter rigor and vicissitudes, and yet with few of the disadvantages of most winter resorts. One would have more pleasure in answering the question if he were not irritated by the perpetual note of brag and exaggeration in every locality that each is the paradise of the earth, and absolutely free from any physical discomfort. I hope that this note of exaggeration is not the effect of the climate, for if it is, the region will never be socially agreeable.

There are no sudden changes of season here. Spring comes gradually day by day, a perceptible hourly waking to life and color; and this glides into a summer which never ceases, but only becomes tired and fades into the repose of a short autumn, when the sere and brown and red and yellow hills and the purple mountains are waiting for the rain clouds. This is according to the process of nature; but[Pg 66] wherever irrigation brings moisture to the fertile soil, the green and bloom are perpetual the year round, only the green is powdered with dust, and the cultivated flowers have their periods of exhaustion.

I should think it well worth while to watch the procession of nature here from late November or December to April. It is a land of delicate and brilliant wild flowers, of blooming shrubs, strange in form and wonderful in color. Before the annual rains the land lies in a sort of swoon in a golden haze; the slopes and plains are bare, the hills yellow with ripe wild-oats or ashy gray with sage, the sea-breeze is weak, the air grows drier, the sun hot, the shade cool. Then one day light clouds stream up from the south-west, and there is a gentle rain. When the sun comes out again its rays are milder, the land is refreshed and brightened, and almost immediately a greenish tinge appears on plain and hill-side. At intervals the rain continues, daily the landscape is greener in infinite variety of shades, which seem to sweep over the hills in waves of color. Upon this carpet of green by February nature begins to weave an embroidery of wild flowers, white, lavender, golden, pink, indigo, scarlet, changing day by day and every day more brilliant, and spreading from patches into great fields until dale and hill and table-land are overspread with a refinement and glory of color that would be the despair of the carpet-weavers of Daghestan.

This, with the scent of orange groves and tea-roses, with cool nights, snow in sight on the high mountains, an occasional day of rain, days of bright sunshine, when an overcoat is needed in driving,[Pg 67] must suffice the sojourner for winter. He will be humiliated that he is more sensitive to cold than the heliotrope or the violet, but he must bear it. If he is looking for malaria, he must go to some other winter resort. If he wants a "norther" continuing for days, he must move on. If he is accustomed to various insect pests, he will miss them here. If there comes a day warmer than usual, it will not be damp or soggy. So far as nature is concerned there is very little to grumble at, and one resource of the traveller is therefore taken away.

But is it interesting? What is there to do? It must be confessed that there is a sort of monotony in the scenery as there is in the climate. There is, to be sure, great variety in a way between coast and mountain, as, for instance, between Santa Barbara and Pasadena, and if the tourist will make a business of exploring the valleys and uplands and cañons little visited, he will not complain of monotony; but the artist and the photographer find the same elements repeated in little varying combinations. There is undeniable repetition in the succession of flower-gardens, fruit orchards, alleys of palms and peppers, vineyards, and the cultivation about the villas is repeated in all directions. The Americans have not the art of making houses or a land picturesque. The traveller is enthusiastic about the exquisite drives through these groves of fruit, with the ashy or the snow-covered hills for background and contrast, and he exclaims at the pretty cottages, vine and rose clad, in their semi-tropical setting, but if by chance he comes upon an old adobe or a Mexican ranch house in the country, he has emotions of a different sort.[Pg 68]

SCARLET PASSION-VINE.

SCARLET PASSION-VINE.