The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Brass Bound Box, by Evelyn Raymond This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Brass Bound Box Author: Evelyn Raymond Illustrator: Diantha W. Horne Release Date: April 6, 2009 [EBook #28509] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BRASS BOUND BOX *** Produced by D Alexander, Josephine Paolucci and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

BOSTON DANA ESTES &

COMPANY PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1905

By Dana Estes & Company

All rights reserved

THE BRASS BOUND BOX

COLONIAL PRESS

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, Mass., U. S. A.

"AT LAST IT WAS OUT"

"AT LAST IT WAS OUT"

CHAPTER PAGE

I. Legacy and Legatee 11

II. Master Montgomery Sturtevant 25

III. Why Monty Did Not Go a-Fishing 40

IV. Foxes' Gully 50

V. Chestnuts and Gold Mines 64

VI. The Brass Bound Box 82

VII. The Grit of Moses Jones 95

VIII. Hay-Loft Dreams 110

IX. Squire Pettijohn 126

X. Alfaretta's Perplexity 142

XI. The Face in the Darkness 154

XII. A Sturtevant—Perforce 168

XIII. But—Sturtevant To the Rescue 187

XIV. On a Saturday Afternoon 203

XV. By the Old Stone Bridge 220

XVI. The Cottage in the Wood 234

XVII. A Self-elected Constable 248

XVIII. Reuben Smith, Accessory 263

XIX. What the Moon Saw in the Cornfield 278

XX. Uninvited Guests 292

XXI. A Neighborly Trick of the Wind 310

PAGE

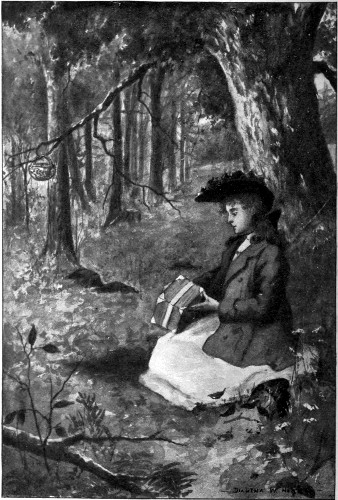

"At last it was out" (See page 81). Frontispiece

"He now lay stretched upon his owner's lap as she still sat on the floor" 27

"'I feel so queer every little spell, an' I must get home'" 97

"There, all anxiety forgotten, they dreamed dreams and saw visions" 120

"Ma'am Puss extracted her own supper in advance of the family's" 148

"Already one pumpkin pie was half-devoured" 230

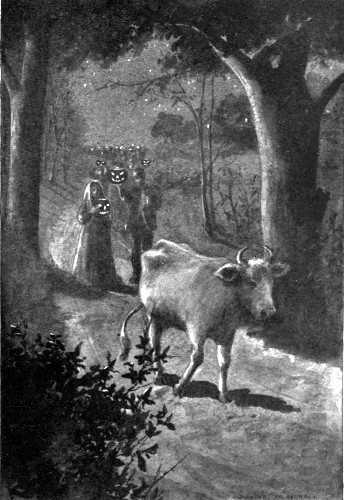

"But the late rising moon looked down upon a curious scene" 290

"Each armed with a grinning Jack and somebody driving Whitey as a snowy guide" 324

Marsden was one of the few villages of our populous country yet left remote from any line of railway. The chief events of its quiet days were the morning and evening arrivals and departures of the mail-coach, whose driver still retained the almost obsolete custom of blowing a horn to signal his approach.

All Marsden favored the horn, it was so convenient and so—so antique! which word typified the spirit of the place. For if modest Marsden had any pride, it was in its own unchanging attitude toward modern ways and methods. So, whenever Reuben Smith's trumpet was heard, the villagers knew it was time to leave their homes along the main street and repair to the "general store and post-office" for the mail, which was their strongest connecting link with the outside world.

Occasionally, too, the coach brought a visitor[Pg 12] to the village; though this was commonly in summer-time, when even its own stand-offishness could not wholly repel the "city boarder." After the leaves changed color, nobody went to and fro save those who "belonged," as the storekeeper, the milliner, and Squire Pettijohn, the lawyer; and it had been ten years, at least, since Reuben's four-in-hand was brought to a halt before Miss Eunice Maitland's gate. Now, on a windy day of late September, the two white horses and their two black companions were reined up there, while the trumpet gave a blast which startled the entire neighborhood.

"My heart was in my mouth the minute I heard it!" declared the Widow Sprigg to a crony, later on; although this curious disarrangement of her anatomy did not prevent the good woman from being foremost at the gate to learn the cause of this salute, thus rudely anticipating her mistress's rights in the case. Therefore, it was upon a time-damaged, cap-frilled countenance that Katharine Maitland's dismayed glance fell as she sprang from the stage and inquired:

"Are you my Aunt Eunice?"

"Your—Aunt—Eunice! Thank my stars, I ain't aunt to nobody!" returned the widow, almost as much alarmed by the appearance of this strange maiden as she had been by the coachman's blast.[Pg 13]

"It is a matter of thankfulness," retorted the girl, pertly, and surveying the other with amused and critical eyes, which made Susanna Sprigg "squirm in her shoes."

Reuben now slowly climbed down from his high seat, and removed from the rumble a great trunk, a suit-case, a parcel of books, and a dog-basket; and the stranger at once occupied herself in releasing from his confined quarters a pug so atrociously high-bred that Susanna instantly exclaimed:

"My stars! That dog's so humbly he must ache!"

Katharine would have given a crisp reply had not her attention been distracted by Reuben's movements, who was waiting to receive his fare, yet in such terror of the pug's snapping jaws that he was stepping up and down in a lively fashion, as he rescued one foot and then the other from his enemy's attack.

"'Pears to blame me for bein' shut up in that there basket, don't he? When anybody knows 'twasn't my fault at all. I hain't enj'yed the trip no more'n what he has, hearin' him yelp that continual, an' I must say I didn't expect, at my time o' life, to commence drivin' stage for dogs. Here, sis, is your change. Good day to ye, an' a good welcome, I hope."

"Humph! You don't speak as if you really 'hoped' it, but quite the reverse!" returned[Pg 14] Punch's mistress, more shrewdly than courteously.

"Dreadful smart, ain't ye?" said Reuben, and drove away, putting his horn to his lips, and thereby drowning any further remarks which the stranger might have addressed to him.

Lifting the ungainly brute in her arms, the girl now turned and surveyed the house beyond the gate, her heart far heavier with homesickness than seemed consistent with her outward, flippant bearing.

What she saw was a wide, rambling frame house; wherever they showed between the clambering vines which encircled it, its clapboards glistening white and its shutters vividly green. The few leaves still left upon the vines were scarlet, while behind the low roof rose maples in the full glory of their autumn reds and yellows. The long front yard was green and well kept, and the borders beside the path were gay with chrysanthemums, though between these showed the frost-blackened foliage of tenderer plants. Upon the porch was a woman with a shawl over her head, apparently shivering in the wind which tossed the maple boughs, and awaiting an explanation of this arrival.

"A pretty picture!" admitted Katharine, who fancied herself artistic, "but so lonesome it gives me the hypo! And that—that, I suppose, is my[Pg 15] Aunt Eunice. Well, Punch, come on! Let's get it over with!"

The Widow Sprigg had remained motionless, but keenly observant, and her thoughts were:

"If that ain't a Maitland, I never knew the breed. And I reckon I do know it, bein's me an' my fam'ly has lived cheek by jowl with them an' their fam'ly since ever was. But which Maitland it is, or what in reason she's come for, beats me."

Then, as the stranger walked coolly through the gateway, leaving her luggage on the sidewalk outside, Susanna sniffed, and remarked—for anybody to hear who chose:

"What's that mean? Expect me to fetch an' carry for such a strappin' girl as that? Well, not if I know Susanna Sprigg, an' I think I do."

Whereupon, the widow, long time "assistant" to her more affluent "neighbor," Miss Maitland, shrugged her shoulders at the wind and this absurd notion, and followed Kate. She wouldn't have missed the interview between that young person and her enforced hostess "for a farm," and yet she was extremely anxious concerning the trunk and the parcels. But curiosity prevailed over caution, and she was in time to hear the rather nervous inquiry:

"Are you my Aunt Eunice—so called?"

"I am Eunice Maitland, and though I am not aunt in reality to any one, I have been lovingly[Pg 16] nicknamed 'aunt' by many of my kin. But no matter what our relationship, you are a Maitland, I am sure, and I am very glad to see you in Marsden. Come in, come in at once. The wind is chill, and you have had a long ride," responded the precise old gentlewoman, extending her hand to Katharine, and cordially attempting to draw the girl within the shelter of the great hall.

But this hospitable attempt was rudely misunderstood by Punch, who snapped at the hand, and caused its owner to withdraw it hastily, saying: "It will be better to leave your dog outside."

"Leave my dog outside! Leave Punch, my—my—my darling! Oh! I can't do that. He has been so tenderly brought up, and is so sensitive to the cold. He has really suffered on that dreadful ride."

Miss Eunice frowned slightly, and merely remarking, "Very well, bring him in, though I caution you against Sir Philip. He is old and irritable," led the way through the wide hall into a sitting-room beyond, where a wood fire was burning on the hearth, and the furnishings were of the sort in vogue a hundred years ago. Even the disturbed young visitor thought she had never seen anything so charming as that simple interior, where everything was in keeping, and so spotlessly neat, and over which fell the cheerful radiance of the blazing logs. Unceremoniously dropping[Pg 17] Punch, she clasped her hands in admiration, exclaiming:

"Oh, how quaint! How interesting! How unlike anything I expected to see!"

Although Miss Eunice was gratified by this tribute to her familiar surroundings, she fancied that its expression was overdone, and resented its seemingly patronizing insincerity. Placing a chair directly in the glow of the fire, she invited Katharine to take it, while she herself sat down on a straight-backed settle beyond.

Sensitive to feel the lessening cordiality of her hostess's manner, Katharine hid her feeling behind an added flippancy, as she tossed her palms outward, in a manner wholly natural to herself, but which the house-mistress again fancied an affectation, and exclaimed: "Well!"

"Well?" returned Miss Eunice, quietly but inquiringly.

"Well, I suppose you're the legatee and I'm the legacy. I hope you won't be half as unwilling to accept me as I am to be left to you. If you are, there'll be some high times in Marsden."

This mixture of frankness and bravado brought a second frown to Miss Maitland's fine face, but she said, quite courteously:

"Kindly explain, my child, who you are, and to what I am indebted—"

"For the nuisance of your legacy," interrupted the girl, excitedly, and, thrusting a sealed letter[Pg 18] into the other's hand, drew back in her own chair and covered her face with her hands. Under all her self-confident manner her heart was throbbing painfully, and she felt as if she must get up and run away. Somewhere in the great forest through which Reuben had driven his coach lay an apparently deserted little cabin, which had attracted her by its overgrowth of woodbine—that hereabout seemed to envelop everything upon which it could clasp its tendrils—and whose memory now returned to her invitingly. Exiled from her own home, an alien here, such a spot as that would be a haven of refuge. She had not known exactly what was in the letter she had tossed Miss Maitland, but she had guessed sufficiently near to know its contents could not be flattering to herself. Beneath her hiding hands her cheeks were flushing with shame when she heard her name spoken with utmost gentleness and affection.

"So you are John's only child! I should have known it without being told, only it is so many, many years since he left me, a wild little lad who found the old home too dull. He was not as close of kin as some others I have reared here, and he was but fifteen when he went away. But I have always loved him, and hoped for his return; and now—"

"Oh, my stars!" inadvertently exclaimed the[Pg 19] Widow Sprigg, thus disclosing the fact that she had been listening beyond the door.

"And now, Susanna, I smell your bread scorching," went on the mistress as calmly as if the other had not betrayed herself. Then, when the kitchen door had been slammed by the retreating hand-maiden, with an emphasis that said as clearly as words that her mistress might go on and talk, and things might happen enough to turn a body's head, for all she, Susanna Sprigg, cared or noticed, so there! Miss Eunice left her own seat, and, going around to Katharine's, gently drew the hiding hands away from the troubled young face, and, putting the letter into them, said: "There, my dear, read it."

"No, no! I can't! I won't! I hate it. I hate her, and all—all—belonging to her! I never want to see or hear of her again. And I won't stay. I see you don't want your legacy, and I'll go at once. I have ten dollars, I can live—"

"Why, there's some mistake, little girl. This is from no 'her,' but—a message from the dead."

The sudden break in the quiet old voice touched the listener more than the words, and she mechanically took the letter as she repeated:

"A message from the dead? What can you mean?"

"Read it and see."

Then Katharine read what her idolized father[Pg 20] had written many months before, when the knowledge of his own approaching death had come to him; and it seemed to her that it was his own voice saying:

"Dear Aunt Eunice:—For dear you are, notwithstanding all these years of silence, during which your wild little lad has grown into a busy, care-burdened man. That you heard of my first marriage, and my wife's early death, leaving me with one little girl—your legacy—I know; because that all happened before the habit of our correspondence lapsed. But you may not know that two years ago I married again, a widow with four little sons; and though she has been the best of wives to me, she and my darling Katharine have not been happy together. Kate is a passionate, self-willed, but great-hearted child, so full of romantically generous impulses that I long ago nicknamed her my 'Kitty Quixote.' Her stepmother's nature and temperament are of quite another mold; and knowing what I have just learned concerning my own health, I foresee nothing but misery for these two, should they be left to live together without my presence.

"So, since my motherless daughter is my most precious possession and you have been my most devoted friend, I find it the most natural thing in the world to bequeath my treasure to my friend. If, for any reason unknown to me, you[Pg 21] cannot accept my legacy I have made other arrangements for Katharine's future, which you can learn by applying to my lawyers, Messrs. Brown and Brown, Blank Street, New York.

"My wife knows of this letter, and we have arranged that after my death, should it occur, Kate is to remain with her for six months, as a final test of their ability to live happily together, and for the benefit of the schools in this city. At the end of that time, if these two well-meaning but uncongenial people decide that it is wisest to part, 'Kitty Quixote' will be sent to you, to do with as you see fit. In any case, she will be no pecuniary charge to any one; her own mother's little fortune, with such a portion of mine as is justly hers, being all-sufficient for ordinary needs.

"In loving remembrance of my boyhood, made happy by your care, and in firm reliance upon your friendship, your troublesome John bids you farewell."

Katharine had expected to find the sealed letter she had been commissioned to deliver to Miss Maitland but a complaining missive from her stepmother, setting forth the girl's faults and failures with that accuracy of detail so characteristic of the "second Mrs. John." That lady's handwriting upon the envelope had helped her to this impression, yet so honest was she that she had[Pg 22] not once thought of protesting or refusing to deliver it. The revulsion of feeling was now so strong that she could not restrain her tears, nor the impulse to throw herself headlong upon Aunt Eunice, crying wildly:

"Oh, it's all true! But he loved me, my father loved me, bad as I am! And for his sake I wish—I wish I could be good. So folks, his folks, or—or anybody could stand it to live with me! But I can't. I've tried. I've tried ever so hard, yet the goodness gets down below and the badness stays on top, and then things go—smash!"

Aunt Eunice waited a moment, then replaced Katharine in her chair, thinking what a child she still seemed, despite her fourteen years and her city training. Also, recalling with a thrill of pride that she herself, at fourteen years, had been the head of her own father's widowed home and a woman, by contrast. "Though I was reared in Marsden," she complacently reflected, as she said:

"I should be glad to hear whatever you choose to tell me, my dear, of your life. Especially, what caused the final break between you and Mrs. Maitland."

"Why, it wasn't badness at all, that time! It was meant in kindness. Some other girls and I had fixed up a sort of house-picnic for washer-woman Biddy's children, who were all down with the measles, and just to amuse them I took stepmother's boys, the four young Snowballs—haven't[Pg 23] they the absurdest name?—along; and she—she didn't like it. She said things. That I'd wilfully exposed them to danger, though I ought to be as careful of them as if they were my real brothers. And there I was trying to be, only she didn't understand. Then, another day, not long before, I coaxed some big boys who have a naphtha-launch to give the 'Balls a sail on it down the bay. The thing happened to explode, and, though nobody was hurt, she went on just terrible because I'd taken the children without asking her. How could I ask her when she was off shopping, or somewhere, just at the very moment the idea popped into my head? And nothing befell the little fellows except getting their clothes wet, and they always needed washing, anyway. The nice part of it was that they were scared into behaving themselves as they should for a whole week afterward, and she might have been pleased. But it was always like that. I'd have perfectly lovely plans for making everybody happy, all around, and they'd all end just the other way. So here I am. Mrs. John has cast me off; do you accept me?"

"First, let me ask if you were accustomed to speak of your father's wife in that manner?"

The girl was surprised by the other's tone, yet promptly answered: "Certainly. Everybody amongst father's artist friends called her either[Pg 24] 'the second Mrs. John,' or 'Stepmother.' Either one it happened. Why?"

"It was most disrespectful."

At this uncompromising reply, Kate stared, exclaiming: "Why, you're a truth-teller yourself, aren't you?"

"I am. Did you not suppose so?" returned Miss Maitland, amused.

"Well, you see, I've been told you were very agreeable, and most of the really agreeable people I know lie like the mischief."

"Katharine!"

"Fact. And I've got into more scrapes for telling the truth than for any other thing I've done, except being kind to the little Snowballs. But—hark! What's that? Punch—Punch—You flippety-cap woman! Stop! Stop! Stop!"

An eruptive, agonized bark from the hall sent the girl thither at a bound, while Miss Eunice hastily followed, anxiously crying: "Philip! Sir Philip Sidney!"

Wildly beating the air with a long-handled broom, her cap-frills flying, her spectacles awry, the Widow Sprigg was vainly endeavoring to restore peace between Punch, the newcomer, and Sir Philip Sidney, the venerable Angora cat which had hitherto "ruled the roost."

The pug, with a native curiosity almost as great as Susanna's own, had slipped from the sitting-room unobserved and had wandered to the warm kitchen where Sir Philip lay asleep on his cushion, unmindful of interlopers till an ugly black muzzle was poked into his ribs, and he found his natural enemy coolly ruffling his silken fur.

Until then, Miss Eunice had boasted of her pet that he was as like his famous namesake as it was possible for any animal to be like any human being, and quoted concerning him that he was "sublimely mild, a spirit without spot." Indeed, Miss Maitland's beautiful "Angory" was[Pg 26] one of the show animals of Marsden. He had been brought to his mistress by a returning traveller more years ago than most people remembered, and had continued to live his charmed and pampered life long after the ordinary age of his kind. With appetite always supplied with the best of food, his handsome body lodged luxuriously, it was small wonder that hitherto he had worn his aristocratic title with a gentleness befitting his historic prototype.

Now, suddenly, the pent-up temper of his past broke out in one terrific burst; and he bit, scratched, tore, and yowled with all the ferocity of youth, while Punch, realizing that he had stirred up a bigger rumpus than even his mischievous spirit desired, vainly sought to elude his enemy's attacks.

"Why, Philip! Sir Philip!" cried Miss Eunice, stooping to grasp her favorite's collar, and by his unlooked-for onrush against her own feet losing her balance and falling to the floor.

"Punch! You bad, bad dog! There—you woman! Don't you dare—don't you dare to strike him with that awful broom! If he needs punishing—I'll punish him myself! Oh, what a horrid place, what horrid folks, what a perfectly fiendish cat!" shrieked Kate, folding both arms tight about the pug's fat, squirming body, and rushing out-of-doors with him. But by this time his courage had returned, and, wriggling himself free, he rushed back to the battle.

"HE NOW LAY STRETCHED UPON HIS OWNER'S LAP AS SHE STILL

SAT ON THE FLOOR"

"HE NOW LAY STRETCHED UPON HIS OWNER'S LAP AS SHE STILL

SAT ON THE FLOOR"

Alas! that exciting affair was all over. Sir Philip's unwonted anger had proved too much for his strength, and, utterly exhausted, he now lay stretched upon his owner's lap as she still sat on the floor, stroking and caressing him most tenderly.

Katharine had followed Punch back to the kitchen, and was as startled as he was proud at the sight before them. Cocking his square head on one side, curling his tail, wrinkling his nose, and protruding his pink tongue even more than usual, he regarded his fallen foe with such comical satisfaction that Katharine's alarm gave place to amusement, and she laughed aloud. But the laugh died as quickly as it had risen when Aunt Eunice looked up and said, reproachfully:

"I fear it has killed him, poor fellow!"

"Oh, no, no! A little bit of a scrap like that kill a cat? I thought they had nine lives, and such a trifle—Why, Punch is as fresh as a daisy, and that proud! Just look at him!" cried the girl. Yet her enthusiasm was dashed by the expression of deep sorrow on Miss Maitland's face, and there were real tears in the widow's eyes as she now advanced, broom in hand, though without apparent anger, to sweep Punch out of the room.

Katharine was too surprised to protest, beyond[Pg 28] quietly motioning the broom aside and lifting the now submissive pug to her shoulder, where he perched calmly contemplative of the disaster he had evoked.

"There, Eunice, don't fret. What can't be cured must be endured, you know, and even a cat can't die but once. Only he was such a cat! We sha'n't never see his like again, an'—Take care there, sis! Don't you know he always hated water?" exclaimed Susanna, resting upon her broom-handle, and bending above her anxious mistress till a dash from the dipper deluged both cat and lap.

Yet now full of sympathy and regret Kate did not pause in her work of restoration, and either the bath did revive Sir Philip or he had been on the point of recovery, for he suddenly sprang up, shook his drenched head, and staggered toward his cushion on the hearth, where he lay down and proceeded to smooth his disordered fur.

Then Kate put her arms around Miss Maitland and helped that lady to her feet, saying, earnestly:

"Oh, I am so sorry, and I am so glad! but it will never happen again. Poor old Sir Philip won't be in a hurry to fight, and Punch never does if he can help it. Do you, you darling?" she finished to the perplexed dog, which she had unceremoniously dropped from her shoulder when she had rushed for the water.[Pg 29]

The pug gave a funny little wink of one intelligent eye, as if he fully understood; then slowly waddled across the rag-carpeted floor and curled himself up at a safe distance from Sir Philip, upon whom he kept a wary watch. But he was a weary dog by that time, and so glad of warmth and repose that he left even his own damaged coat to take care of itself for the present.

However, if he was calm, the Widow Sprigg was no longer so. Kate had not only drenched the cat and his mistress, but she had left a large puddle in the very centre of Susanna's "new brea'th" of rag carpet, its owner now indignantly demanding to know if Miss Eunice "was goin' to put up with any such doin's? That wery brea'th that I cut an' sewed myself, out of my own rags, an' not a smitch of your'n in it, an' hadn't much more'n just got laid down ready for winter. An' if it had come to this that dogs and silly girls was to be took in an' done for, cats, or no cats, Angory or otherwise, she, for one, Susanna Sprigg, wasn't goin' to put up with it, an' so I tell you, an' give notice, according."

During the delivery of this speech the widow's black eyes had glared through her spectacles so fiercely that the young visitor was alarmed, and said to Aunt Eunice, appealingly:

"Oh, please don't let her go just because I've come! I'll not stay myself, to make such trouble,[Pg 30] even if you'll have me—and you haven't said so yet. There's that boarding-school left—"

Miss Maitland ignored the appeal, but looking through the window remarked to her irate assistant:

"That luggage shouldn't be left on the sidewalk, Susanna. Get Moses to help you bring it in. If a tramp should happen to pass he might make off with it."

By which quiet rejoinder Kate understood that she had been "accepted;" also that the house-mistress was not disturbed by the threat of her handmaid. Indeed, she discovered afterward that it was the widow's habit to threaten thus whenever her temper was a trifle ruffled; also, that nothing save death was apt to sever her relationship with the Maitland family, which she held far dearer than her own.

"Tramps? Do you have tramps in this out-of-the-way village? I'm afraid of tramps, myself, and they're about the only things I am really afraid of," said Kate, following Aunt Eunice back into the sitting-room.

"I never knew one to pass through Marsden, and I've lived here always; but Susanna has read of them and their depredations, and is constantly on the lookout for one. Except for the trouble between the cat and dog she wouldn't have left your things in the street a moment after she had satisfied her curiosity concerning you.[Pg 31] But you will like Susanna when you have become accustomed to her. A better-hearted woman never lived."

To this assurance the girl replied with a doubtful laugh and the words:

"I never should have dreamed it;" then stationed herself at the window to watch the proceedings outside.

The Widow Sprigg had vanished through a back kitchen and now appeared around the corner of the house, having in tow an elderly man, who followed her with evident reluctance. She had thrown on a "slat" sunbonnet, and pinned a red shawl about her shoulders, but had shaken her head so vigorously that the shawl had slipped down and the sunbonnet back, while the frills of her muslin cap waved blindingly before her spectacles.

"Who is that? Is he 'Moses'? Does he live here?" asked Kate, laughing not only at the appearance but behavior of the two.

"Yes. He is my hired man. His name is Moses Jones. He is not as old as he looks, and is one of our likeliest citizens. He's quite intelligent, and has even been mentioned for a constable—if Marsden should ever need one. If enough city people should come here to warrant such an office," finished the lady, with unconscious sarcasm.[Pg 32]

Kate's head came around with a jerk. "Constable? That's a policeman, isn't it?"

"Yes."

"And is it only 'city people' who do wrong and need arresting? Because, you see, I'm a 'city' person myself, and resent that idea!" laughed the girl, mischievously. Yet the next instant she regretfully observed that she had again annoyed her dignified hostess.

Indeed, the annoyance was so great that Miss Maitland's brow clouded, and her eye swept the stylishly garbed small figure at the window with renewed misgiving. She knew little of the latter-day young folks, with their study-sharpened intelligence, their habit of repartee, and their self-assumed equality with their elders. Such few of the Marsden lads and lasses as visited her belonged to the old-fashioned families, and were trained to strict habits of obedience, and "to speak when they were spoken to." They were supposed to have no opinions on any subject save such as were formed for them by their parents and guardians; and—well, they were altogether different from this alert, dark-eyed maiden, who had been in the house less than an hour, yet had already upset it to a degree!

Kate's gaze had again returned to the scene without, and she had forgotten her momentary regret, as she observed, from time to time:

"She's the funniest thing I ever saw, and he's[Pg 33] funnier than she! He doesn't want to lift the trunk. No. She doesn't want him to. Yes, she does. She's getting mad. He won't do it her way. She won't do it his. They're both coming in and leaving it on the sidewalk. He's saying something to her and now she's faced about again. Maybe he said 'tramp,' because she's looking all up and down the street as if she were scared, and he's laughing. I guess he's laughing—he shakes as if he were, yet his face is as sober as ever. Now they're off! Here they come. But do look, Aunt Eunice, oh, do look! He's just barely lifting his end off the ground, and she's raised hers real high. She's doing the most of the work, I believe, yet he's crouching down as if he were half-crushed by the weight. The idea! He sha'n't do that! I won't let any woman be treated that way!"

Out she sped, leaving all doors open and thus obliging Miss Maitland to close them after her or let the rooms be cooled by the inrush of wind. But her swift comprehension of the habits of the two household helpers, and her vivid description of their present movements, had so amused the lady that she also took up a point of observation, and was just in time to see Katharine indignantly push Moses' hand from the trunk-handle and seize it herself. It was evidently a heavier load than she had expected, for, at first, her end went down even lower than when Moses[Pg 34] held it, yet she rallied instantly, and with all her might lifted it to a level with Susanna's, who was as instantly won by this action, and exclaimed, exultantly:

"There, Moses Jones! What did I tell you? Ain't no heft in it, not a mite. Nobody but a man—a man—would make such a how-de-do over a trunk. Just a trunk!"

The infinite scorn of words and manner provoked nothing further from her "shif'less" housemate than another silent chuckle, and a keen glance at Katharine from beneath his bushy eyebrows.

Yet he did look a trifle ashamed when his mistress herself opened the hall door again to admit the trunk-bearers, and without more ado hurried back to the sidewalk and brought in the rest of the luggage. It was noticeable that he no longer stooped or affected fatigue; and that as soon as Susanna let go the trunk at the foot of the stairs he immediately shouldered it, like the lightest of parcels, and carried it swiftly above. Then, pausing at the top of the flight, he asked, in a brisk tone:

"Which room, Eunice?"

"The sitting-room chamber, Moses."

Katharine listened, astonished, then exclaimed:

"Why—I thought he was your 'hired man.' That's servant, isn't it?"

"About the same thing, my dear," answered[Pg 35] Miss Maitland, smiling ever so slightly, and quite conscious that Susanna's black eyes and keen ears were alert for her reply.

"But he called you by your first name! just as if he were your brother, or—or—somebody."

"There is little giving of titles in Marsden, Katharine, but that does not imply any lack of respect. Moses and Susanna and I were schoolmates together in the little red schoolhouse at the crossroads, and none of us—none of us—wish to forget it. The same old schoolhouse where your father learned his letters, and where you will go if you are happy enough with me to remain. Now, Widow Sprigg, let John's little girl see what sort of a supper you used to fix for him when he was hungry."

All fancied slight at the term "servant" thus atoned for by the formal "Widow Sprigg," and her favor swiftly won by Kate's behavior with the trunk, the housekeeper departed in high good-humor, her cap-strings flying, spectacles pushed to the top of her head, and cheerily remarking:

"So she shall, so she shall. I'll show her. For Johnny was the boy to eat an' enj'y his victuals. 'Twas a comfort to cook for him, he was that hearty. I'll have it ready in the jerk of a lamb's tail."

Moses came down the stairs and went out "to do his chores," casting another keen glance at the stranger ascending them with Miss Maitland to[Pg 36] the sitting-room chamber. For the girl's marked resemblance to a boy he had known and taken fishing many a time, he was inclined to like her; but because of the probable altered household life, and her swift perception of his whimsies, equally inclined to dislike; and he shifted the straw from one side of his mouth to the other, reflecting:

"Well, it's more'n likely she an' Eunice won't gee. Eunice has raised six seven of her folkses' childern, an' I 'lowed she'd got done; but there ain't no accountin' for silly women—silly women. Get out, there, you! Strange that a body can't leave a gate open a single minute here in Marsden village, without somebody's stray cattle trespassin'. Get out, I say!"

The plump white cow, which had obtruded its nose through the gateway, calmly withdrew it and proceeded on its way undisturbed by Moses' frantic gestures. Miss Maitland's was not the only dooryard in the village where grass was still abundant, and Whitey knew it.

"That's old Mis' Sturtevant's critter again! She's no right to turn it loose to feed along the street, that-a-way. Course, she's set Monty to watch, an' he's gone off a-fishin'. That's as plain as a pike-staff. Pshaw! Folks so poor they can't feed their stawk hain't a right to keep any, I declare! When I get to be constable I'll straighten some things in Marsden township that's terrible crooked now; an' the very first one I'd complain[Pg 37] of or arrest would be that lazy little stutterin' Monty Sturtevant!"

"W-w-w-wo-would it?"

The voice came from beneath the white lilac bush, but it seemed to come from the earth, and Katharine, at the just opened sitting-room chamber window, saw the whole affair, and laughed aloud.

Her laughter startled the intruder as much as he had startled Moses, and he came out of hiding, demanding:

"W-w-who's t-t-that? Aunt Eu-Eu-Eu-Eunice got comp-p-pany?"

"Yes. But that's no concern of yours," snapped the hired man, "and you best go 'tend your cow;" finishing his advice with a threatening nod.

"Oh, f-f-f-fudge! Wait till you get to be co-co-constable, then shake your h-head. W-w-who is it, I say?"

"I hain't been told, but I 'low she's some cousin forty-times-removed to Eunice, come to sponge a livin' out of us. But she needn't worry you none. She hain't come to your house to upset things."

"G-g-glad of it!" returned this ungallant young Marsdenite. "But say, Un-un-uncle M-Mose."

"Now, Monty, none o' that. I know what's afoot when any you boys begin to 'uncle' me,[Pg 38] an' I say 'No.' I ain't goin' to give up my night's rest for a fishin'-trip. You hear me?"

"B-b-but, Uncle Mose! I've got the b-ba-bai-bait all dug, and it'll be p-p-pr-prime for fishin'. Say, Uncle Mose, we haven't had a s-s-s-single speck o' fresh me-me-meat 't our house for a w-w-w-week!"

"Montgomery Sturtevant! That ought to make you stutter an' choke! Eunice sent your grandma a pair o' pullets no longer ago 'n yesterday. You—"

But Monty had already departed to summon his chums for an evening's sport. Well he and they knew that the shortest road to the hired man's heart was by the suggestion of hunger; and the surest way to secure parents' consent was the announcement:

"Uncle Moses'll take us fishin', if you'll let us go."

Moses again turned his face chore-ward; yet it was noticeable that he paused to examine his "tackle" before he fed the poultry, and that he softly whistled as he went about his work. He was even first at the rendezvous, on the old "eddy road;" and though others joined him there, Montgomery—at once his dearest delight and greatest torment—did not appear.

Alas! at that moment the impecunious heir of all the Sturtevants was himself in anything but a whistling mood; and was thinking direful[Pg 39] things concerning a girl with whom he had not yet exchanged a word.

"The h-h-h-hateful young one! Un-un-uncle Mose said 'none o' my wor-r-ry,' an' that's all he k-k-knew! Plague take her! W-w-what she come to M-M-Ma-Marsden for an' drive me plumb cr-cr-craz-crazy!"

Montgomery's love of gossip was his own undoing. When, after the manner of Moses, worthy guide, the young angler had put his own fishing-tackle in order, he sought the dining-room, where supper awaited. For once he was on time, and received a word of commendation from his grandmother, which so elated him that he mentally reviewed the day's events for a bit of news with which to enliven her monotony. Then like a flash arose before him the picture of an unknown girl at Miss Maitland's window. This was something worth telling, indeed.

With his mouth full of chicken, remnant of Eunice's pullets, he burst forth.

"A-a-aunt Eunice's got comp'ny."

The punctilious old lady opposite raised her thin hand, protesting: "My son, you should never attempt to talk when you are eating."

Nothing abashed, the boy swallowed hastily and reiterated his statement. At which Madam[Pg 41] Sturtevant exclaimed, with as much excitement of manner as she ever showed: "Company? Dear Eunice entertaining guests? Why, son, how did you learn that? Who are they, pray?"

"D-d-didn't say 'g-guests.' She's a g-g-gir-rl. How I learned, I s-s-saw. With my own eyes. M-m-more chicken, g-gramma."

"Yes, dear heart. It is delicious poultry, and so sweet of Eunice to remember us. We were always close friends, and she is still a lovely woman. So fresh and young looking. But then, Eunice never married nor was widowed, nor exchanged wealth for poverty, nor reared a—a grandson," concluded the dame, fixing a too thoughtful gaze upon Montgomery's freckled face, whose only aristocratic feature was a pair of exceptionally fine eyes. Her mind was already wandering back into that past which held so much more of interest to this decayed gentlewoman than the present; but, wriggling under her survey of himself, the lad reminded her that Miss Maitland had also had her trials, in that:

"Un-un-uncle Mose s-says she's raised s-s-s-six sev—en other folks' ch-ch-ch-childern, anyhow."

"Sixty-seven children! My dear, you must certainly have misunderstood. But no matter. Finish your food at once. Our duty is plain. I dislike going out, except on Sundays, and especially at evening, yet dear Eunice would think me most remiss if I delayed to pay my respects to[Pg 42] any guest of hers. I am dressed sufficiently well for an informal visit, but—" here the old lady put on her glasses and critically regarded her grandson's attire, then remorselessly continued: "But you, my son, must take a bath and put on your best suit. As soon as possible; because the stranger will be tired and wish to retire early. Finished? That is well. Strike the bell for Alfaretta."

Though his plate was still heaped with the choice portions of the fowl, which his doting grandmother had preserved for him, and though he was still hungry, unlucky Monty sank back in his chair, a limp, crestfallen lad. With his dejected stare fixed upon her unrelenting face, he stammered forth:

"B-b-but, g-g-gr-gramma! I'm goin' a-f-f-fishin'!"

"Nonsense. Get ready immediately," said Madam, rising from table, and measuring out the supper portion of Alfaretta, the one small servant of a house which had once sheltered many.

Then he also rose, but so languidly that "Alfy" stared, and, glancing toward his still full plate, inquired: "You sick?"

"No, I ain't. I'm m-m-mad!"

"At me?"

"N-no. Y-y-yes. You're another of 'em. She's a g-g-girl. I've got to go s-s-s-see her! Just a p-p-plain girl!"[Pg 43]

The infinite scorn with which this reply was hurled at her touched Alfaretta's pride. Was she not, also, a girl? Said she, with intent to "get even" for some of his former toplofty remarks: "Oh! I thought you was goin' fishin' with Uncle Mose. I saw Bob Turner go past, quite a spell ago, and he was whistlin' like lightnin'. And I heard you say, more'n once, 't you 'hadn't no man to boss you—you could do as you pleased."

"So I can when—when g-g-gr-gramma ain't r-r-round," replied he, so meekly that Alfaretta relented. She had been intending to add the contents of Monty's plate to the less appetizing portion set out for herself, but now determined to put aside for a future luncheon whatever he had left. Food was never overabundant at the Madam's, and Alfaretta made it her business that none of what there was should ever go to waste.

"Never mind, Monty. To-morrow ain't touched yet, an' there'll always be fish in the pool," comforted the little maid with real sympathy, for, despite the fact that he teased her continually, she loved him sincerely.

But he merely banged the door behind him as he departed to his toilet, feeling himself the most abused of mortals. For if there was anything which this "last of the Sturtevants" hated worse than paying a visit it was taking a cold bath in a tub, an ordinary wooden wash-tub! To have both[Pg 44] bath and visit imposed upon him in one fell hour, was an undreamed-of calamity.

Therefore, it was a very different appearing youth from his ordinary merry self who was presented to Katharine in Miss Eunice's lamp-lighted sitting-room an hour later. In outward matters, also, a vastly improved one, since his rough denim blouse and overalls had been exchanged for a fairly modern suit, thoughtfully supplied him by wealthier relatives; his tangle of close-cropped curls brushed smooth, and his face freed from all spots save freckles.

"Katharine, you may take Montgomery over to that little table where the photograph albums are, and show them to him. You and he should be good friends, as all the Sturtevants and Maitlands have been for generations before you," said Miss Eunice, after the presentation had been made, and during which ceremony Monty had wisely refrained from speech.

"Come on, then, and I'm awfully glad to see you. I began to think there wasn't a single young person in this Marsden, for all I've seen so far have been gray-haired," said Kate, leading the way to the table, where a shaded lamp shed a pleasant radiance. But, having arrived there, she coolly pushed the albums aside, and remarked:

"I hate looking at photographs. Don't you? They're commonly so inartistic. I'd much rather talk."[Pg 45]

By this time Monty was staring with wonder at this creature, who was one of the despised "girls," who had laughed at him from the window, and whose speech and appearance were so unlike those of all other girls he knew. She didn't act shy nor silly, nor drop her g's, nor pretend "politeness," nor wear her hair or clothes as they did. She was just as frank and unabashed as a boy among boys, and the visitor began to be glad that he had come. It would be something worth while telling at school to-morrow, that he had already made acquaintance with Aunt Eunice's unexpected company, and that she was real nice.

Something of her charm vanished, however, when she ordered, peremptorily: "You begin."

Now, although the boy outwardly made light of his own affliction, he was in reality extremely sensitive concerning it, and naturally he was not inclined to open conversation with this stranger whose own tongue was so glib. He, therefore, contented himself with turning his great blue eyes, fringed with such wonderful lashes, full upon her, and smiling beatifically. So cherubic was his expression, indeed, that at that instant Madam, chancing to turn her gaze that way, touched Miss Maitland's arm and directed that lady's attention toward him, whispering:

"Isn't he lovely? Isn't he clear Sturtevant?"

"Yes, he is Sturtevant, indeed," assented Aunt[Pg 46] Eunice, but with a sigh that did not betoken satisfaction. "He has the Sturtevant vanity, Elinor, to the full. You should correct him of it at once. He's a fine lad—in some respects."

It proved that Montgomery was to be corrected, and at once, though not by his indulgent guardian. It was Katharine's part to do that, as she opened her own dark eyes to their fullest, and exclaimed:

"Well! You're the first boy I ever saw make goo-goo eyes! The very first boy. They're quite pretty, but I'd rather hear you talk than look at them. Tell me things. I've come to this village, and I've got to stay. I'm a legacy. I'm left to Aunt Eunice yonder, and she can keep me long as she likes. When she doesn't like, she can send me to boarding-school. I'm an orphan. I hope she will like, because I love her already, only she's so correct I know I shall shock her a dozen times a day. I'm fourteen years old. My home was in Baltimore. I came on to New York yesterday with a friend of the second Mrs. John's—I mean, of Mrs. Maitland's—and stayed there last night. To-day I came on the train as far as it went, then in the stage with the queer driver blowing a horn. It was just like a story-book. This home, too, and everybody might be out of a story-book, all so unlike anything I ever saw. But, I beg your pardon. I've just thought that, though you seem to hear well enough, maybe you[Pg 47] are dumb. Are you? Because if you are I can talk a little myself in the sign language."

This was too much. Monty burst forth in self-defence, and to stop that running chatter of hers:

"N-n-n-no! I-I-I-I—"

Then silence. Katharine had never before met a person who stammered, and she was utterly astonished. At that moment, also, there was a lull in the animated conversation which the two old ladies opposite had hitherto kept up, so that Montgomery's loud yet uncertain protest fell like a bomb on the air.

However, the silence was not to last. Katharine recovered from her surprise, and demanded, indignantly:

"Why do you say 'I-I-I-I'? Are you mocking me? because if you are, I consider that more ungentlemanly than to make eyes."

"No, Kate, Montgomery is unfortunate. He stutters. You should apologize. To jeer at the infirmity of others is the depth of ill-breeding," interposed Miss Maitland, hastily crossing the room and laying a reproving hand upon the girl's shoulder. Then she continued, smiling affectionately upon the lad: "But we who all know and love Montgomery are sure that he will, in time, overcome his impediment. 'Tis only a matter of practice and patience."

The boy made no reply, but sat with down-bent head and flushing face, wishing again, as when this[Pg 48] dreadful visit was appointed him, that Katharine Maitland had never set foot in Marsden village. Longing, too, with a longing unspeakable, to retort upon her with a volubility and sharpness exceeding even her own. But all unconsciously his pride had received just the sting needed, and his angry thought, in which there was no halting stammer, was this:

"I'll show her! I'll let her see a Sturtevant is as good as a Maitland any day! I ain't vain. She sha'n't say it. I have got nice eyes, folks all say so, and it's easier to talk with them than with my crooked old tongue. But I'll conquer it. I will. Then I'll show her what kind of a girl she is to dare—"

To dare what?

In all his previous ignominy there was naught compared with this. For here was Kate, remorseful, warm-hearted Kate, who never meant to give a single creature pain, yet was forever doing it, Kate—down upon her knees clasping Monty's neck with her arms, kissing and beseeching him "not to mind," exactly as she would have kissed the smallest of all the Snowballs, and not resenting it in the least because he did not instantly respond to her entreaties.

Respond?

For the space of several seconds it seemed to the lad that his head was whirling on his shoulders like a top. Then, with all the rudeness of his[Pg 49] greater strength, he flung the demonstrative girl aside and rushed from the house. One idea alone was clear in his troubled brain: that he must get away from everything feminine and go where there were "men." The fishing-pool. Uncle Moses and the boys. The thought of them was refreshment, and put all other thoughts, of disobedience and its like, far from him. Striking out boldly, yet half-blindly through the dim light, he crossed Miss Maitland's orchard, took a short cut by way of the great forest—which he nor no other Marsden lad would ordinarily have entered alone after nightfall—on past the "deserted cottage" in the very heart of the wood, and then—oblivion.

When next Montgomery opened his eyes his head lay on something soft, and he confusedly tried to understand what and where it was. But thought seemed difficult, and he closed his lids again, wondering what made him feel so weak, and drowsily deciding that he must be in his own bed and this the middle of the night.

In one thing he was correct—it was the middle of the night; a later hour than the boy had ever been absent from home, even upon the most prolonged of fishing-trips. Yet the softness beneath his head was not that of a pillow in its case, but the lap of a white-frocked girl, who was holding him tenderly and sobbing as if her heart would break.

"W-w-wh-where 'm I a-at? Who's a-c-c-cr-cry—in'?"

"Oh, you darling boy! you didn't die, did you, after all! Oh, I'm so glad, so glad, so glad! And I thought I had killed you. I'd never killed[Pg 51] anybody before, though stepmother said I'd tried. I mean I—I suppose I scared you some way, I don't see how, for the minute I was good to you and sorry, you ran away."

Montgomery moved uneasily. He began to remember events distinctly; quite too distinctly, in fact. He had run away from that horrid girl, and he had forgotten the ravine beyond "deserted cottage." He had fallen down it and hit his head. He could recall the dreadful sensation of pitching forward into a seemingly bottomless pit, and shivered afresh at the memory.

Feeling him shiver thus, Katharine drew her white skirts around his shoulders, and cossetted him as if he had been a baby. He tried to wriggle away from her on to the ground beyond, but this she sturdily prevented, and the late-rising moon cast its light just then upon a face, oddly set and determined for that of so young a girl.

Finding himself helpless in that strange weakness, Monty ceased to wriggle, and demanded: "How y-y-y-you get here, a-a-a-nyway?"

"Oh! I just followed. When you ran away I ran after."

"A-a-a-aunt Eu-Eu-nice let you?"

"I didn't stop to ask her permission. I saw I'd hurt your feelings, and I couldn't let you go without telling you I was sorry. But, you see, I never before knew anybody who stammered, and I didn't think how rude I was to mention it.[Pg 52] Not till Aunt Eunice pointed it out. I do beg your pardon, sincerely. Will you forgive me?"

It was not in the spirit of any Sturtevant, past or present, to decline an apology so sweetly and earnestly offered. Besides, that was as it should be. Humility was the correct attitude for insignificant girls toward such superior creatures as boys, and Monty waxed magnanimous, replying:

"Oh, y-y-es! I'll f-f-forgive you. But I don't see. G-g-gir-ls can't run like boys."

"Can't they, indeed? Well, you ran like a hare, and I just as fast. There was mighty little space between us, honey, and you may believe it. How else should I have known the way? I had to keep you in sight, of course. It was so fearfully dark in that forest that I nearly lost you once, but I could hear if I couldn't see; and it wasn't so bad when we got outside again. Yet whatever should make you, a boy—a boy!—go and hurl yourself over a precipice, when you knew all the time it was there, while I, a girl—a girl, if you please! who didn't know a thing about it—stopped short on the brink, amazes me. Explain it, won't you?"

"Oh, f-f-f-fudge! Must be aw-aw-awful late. Moon don't rise now t-t-till 'most m-m-morning," observed Montgomery, declining explanations, and wondering how she had perceived his distaste for girls. Besides, he was rapidly regaining strength, and now when he raised himself an[Pg 53] inspiration came to him. The inspiration found voice in the words:

"M-m-m-might's well be hung for a s-s-s-sheep as a l-l-l-lamb."

The observation was apparently so senseless and Katharine's love of mimicry so strong that she couldn't help replying and laughing: "J-j-j-just as w-w-well. But where's the s-s-s-s-sheep and l-l-lamb in the case?"

Montgomery did not now resent her imitation of his very tone. He even condescended to laugh back; then ungallantly remarked: "I wish y-y-you'd go h-h-home."

"Meaning to Aunt Eunice's. That's exactly what I want to do. So let's be off."

"I s-s-said y-you," corrected Master Sturtevant, rising and taking a few cautious steps to test the state of his legs. He found them usable, though rather wobbly about the knees, and would have started off across the ravine's bottom had not Katharine caught and held him. She was herself shivering violently, but only from the cold of an autumn midnight, against which her light summer dress was small protection. She ached from long sitting on the stony ground, and from holding the heavy shoulders of her companion. She was frightened by the lateness of the hour and the intense loneliness of the place; and she felt that she had sacrificed herself for just the very meanest boy who ever lived. Though she was not a[Pg 54] girl who often cried, tears came then, and that worst of all feelings—homesickness—seized her and turned her faint.

Poor Monty! Here was a situation, indeed, for a boy who despised girls! Yet also a boy who was a gentleman by birth; so that, while his first impulse was to run away, his second was to offer such comfort as he could.

"W-w-what you cryin' for, a-a-anyway? I-I-I'm all right, I guess."

"Well, if you are, I'm not. I'm just as anxious to go home as you are, only how can I? I don't know the way, and I'm afraid. I'm afraid of everything! Of that terrible forest, of Aunt Eunice's anger, of her refusing to keep me and sending me off to that boarding-school, of—Oh, dear! I wish I was back in Baltimore!"

Never had the cold countenance of the second Mrs. John or those of the round little Snowballs seemed so humanly lovable to Katharine as they did at that moment, remembering them in her banishment.

"F-f-fudge! Q-q-quit it! If we're goin' to get scolded for part, might's well b-b-be for the w-w-w-whole. 'Tain't far to the pool. We can go f-f-fishin', after all, if you behave. I th-th-thought you was good as a boy, an'—Will you?"

Kate dried her eyes. She didn't enjoy grief, and the prospect of any novelty was delightful.[Pg 55] She forgot that she was cold, that it was late and she was where she should not have been at such an hour, and exclaimed, with an eagerness equal to Montgomery's own:

"Oh, let's! I never went fishing in my life!"

"Come on, t-th-then!" cried the relieved lad, now readily taking her cold hand and setting off with all the speed he could attain.

The moon was shining brilliantly, making every object as distinct as day, and to the city-reared girl the scene was like fairy-land. Her spirits rose to the highest, and none the less, it may be, because all the time she was conscious of a certain daring and danger in their escapade; and her pace more than outstripped Monty's as they crossed the short distance to the river, warming themselves by their own speed, and listening intently for the sound of voices which should have reached them long before.

"Oh, I'm so delightfully goose-fleshy! This is the most thrilling adventure of my life! I begin to feel as if I were part of a story-book myself, like all the rest of Marsden!" said Kate, half-breathless with running, when her mate came to a sudden halt among the shadows of the trees beside the famous pool.

"S-s-s-sh!" warned the other, leaning forward at the risk of a tumble into the still, deep water, listening and peering up and down the stream. Then, with disappointment depicted in every line[Pg 56] of his suddenly weary body, he gloomily stammered: "Th-th-th-they've gone home!"

There was nothing left but for themselves to follow; but surely, there were never fields so wide and rough as these over which Master Sturtevant now guided Katharine; herself, also, so tired from her day of travel and her night of adventure; and finally, feeling as if the stubble pierced every inch of her thin shoes, and that she could endure the discomfort no longer, she begged:

"Oh! please do go by some road, and not on this grass any longer."

"Huh! 'T-t-tain't grass. Oat-st-st-stubble," he explained, doggedly keeping on his way, which he knew was shorter, and for the further reason that he could rid himself of her at Miss Maitland's back garden fence. From there he meant to make his own rapid transit to his grandmother's low kitchen roof and through a window to his bed, as he fondly hoped, forgotten and unobserved. He didn't intend that any strange girl should throw all his plans agley, for she had done more than mischief enough already. Yet even as he spoke, he looked furtively around and was dismayed to see how white she was, and how big and troubled her dark eyes were. Fudge! They were even larger and finer than his own blue ones, yet she had not once seemed conscious of the fact.

It was the Madam's opinion that "blood would[Pg 57] tell," and the good blood of many past Sturtevants stirred now in their descendant's veins, rousing his unselfishness, and making him say:

"F-f-fudge! You look b-b-beat out. I'll go the road, all right. I don't m-m-m-mind it—m-m-much, not much;" for even chivalry could not prevent this last truthful word of regret.

So by the road they went; and by the road—retribution came. Nemesis in the form of Moses Jones; no longer in a mood to be "uncled" by any boy, not even Montgomery, and in his sternness grown almost unfamiliar. He was not alone. Two neighbors were with him, and, despite the fact that the moon was shining, all three men carried lighted lanterns. They were overcoated and muffled to a degree, and Moses' first action was to unfold a great shawl which he had carried on his shoulder, and wrap Kate in it. He did this in silence, not so much as asking "by your leave," and not observing that he was smothering her at the same time. Then he took hold of her arm through the folds of the shawl, and, facing about, started back along the route he had come.

They were well outside the village limits, and a weary tramp yet lay before them, the longer strides of the men taxing the fatigue of the children, till it seemed to them both as if they must fall by the way. That terrible silence, too, and the firm grip of her arm, made Kate wonder if Mr. Jones had suddenly become a constable in fact,[Pg 58] and if she were the first victim to be arrested. Once she wriggled herself free from her captor's hand, only to find herself again secured and even more rigidly.

As for poor Montgomery, the pain and confusion had returned, and he could think of nothing save that tormenting headache. His temple was swollen and throbbing, and the one idea he still retained was a longing for rest. It seemed to him that he had been hurried and tramping along ever since he was born. That never had he done a single thing besides lifting one heavy foot after another and planting each a bit farther along that glaring road. The lanterns bobbed about outrageously, as if they were trying to make him more dizzy still; and he scarcely knew when they entered the now deserted village street and came to a halt at Miss Maitland's gate.

There, he fancied, some women rushed out and grabbed Katharine, for he dimly saw her borne away into the house where more dazzling lights were gleaming. To avoid their bewildering rays he closed his eyes a moment; and when he opened them again he found himself being carried swiftly homeward in Moses' strong arms. He being carried! like one of Mis' Turner's babies! More ignominy still. As if his having been coddled and wept over by a strange little girl hadn't been mortifying enough. But his own voice sounded[Pg 59] queer to him as he tried to say, with unstammering distinctness and dignity:

"You—needn't carry me n-n-none, Un-un-uncle Mose. What you doin' it for? Put me d-d-down!"

The other two men had vanished, and there was nobody to hear Uncle Moses' tender, troubled answer:

"Why, you poor little shaver, lie still. I don't know what's happened ye, nor what sort of scrape you've been in. You an' that t'other one, who's come to turn things topsyturvy. But betwixt the pair of you you've nigh druv two old women crazy, and set the whole village a-teeter. Just because I walked through it ringin' a bell an' cryin', like any respectable constable would have done if I'd been one, and this 'most makes me feel I am, just cryin': 'Child lost! Boy lost! Girl lost!' and a couple the neighborin' men j'inin' in the search, with our lanterns lit, sence we didn't know what sort of a hole or ditch you might fell into—"

"F-F-Foxes' Gully!" exclaimed Montgomery, no longer resisting the relief of walking on somebody else's feet, so to speak.

Uncle Moses stopped short, amazed and alarmed. "What? What's that you say?"

"F-f-fell down it. An' she come to say she was s-s-s-sor-ry."

"And wasn't killed? Well now, and forever[Pg 60] after, I'll believe in guardeen angels! Fell down it an' wasn't killed! But what made ye? Hadn't you any sense? Why, there's been more'n a half-dozen cattle killed in that plaguey hollow sence I can remember. Yet you wasn't. Well, I'm glad of it," and though this seemed a very mild expression of his satisfaction, the sudden squeeze which Moses gave his burden emphasized it sufficiently.

For a few minutes neither spoke again, then Monty suddenly asked: "How many you catch, Un-un-uncle Mose?"

"Enough for breakfast. But I missed ye, sonny, I missed ye. An' I'm real glad you wasn't killed. As for that t'other one, I declare, I wish't she hadn't come. 'Peared like Eunice would lose her seventy senses, a-worryin' lest the child take cold or get hurt or somethin'. And there she has landed on her feet sound as a cat. Though speakin' of cats, Sir Philip has had the bout of his life, and he looks pretty peaked to me. But here we are to home, an' your grandma ain't likely to scold you none if you just mention to her 'Foxes' Gully.' 'Twas one of the Sturtevant calves got killed there, the very first off, an' she will remember. As for me, a respectable hired man, kep' out of my bed like this—why, sonny! Soon's you get over it I'll teach you a lesson you'll remember!"

So, still grumbling and petting, Moses set his[Pg 61] burden down in Madam Sturtevant's presence, and saw her open her lips to reprove her erring grandson, then as suddenly close them again and strain the boy to her heart, while her stately figure shook like an aspen. But Moses knew the lady's temperament of old, and how her alternate severity and indulgence had been bad for the child she idolized, and, fearing that severity might have the upper hand now, when it was least needed, he remained long enough to mention:

"Nothin' much the matter with the little shaver, Madam, only he fell down Foxes' Gully, and is—he's sort of tuckered out."

Then he quietly withdrew, and of Montgomery Sturtevant he had no further glimpse during what he himself termed "a consid'able spell."

As for Katharine, she was sound asleep long before Moses returned from Madam Sturtevant's. To the anxiety and reproof with which she had been received, she had, fortunately, but little to say beyond the statement that, "I went to apologize, and I stayed to—to fish, I guess." The relief of being safe indoors again was all she realized, just then, and she submitted to being warmed, blanketed, and dosed with hot sage tea, with a meek humility that won her pardon.

Indeed, when at last the dark curls rested on the pillow, and the childish face softened in slumber, she looked so like Aunt Eunice's lost "little John," that the lady stooped and kissed her for[Pg 62] his sake. But she confided to the faithful Widow Sprigg, who had also watched and waited:

"I'm afraid, Susanna, that our peaceful days are over. While she was out to-night, and I knew not where, and I was so troubled and anxious, I felt that it would be wrong, really wrong to burden myself with such a charge. For years her father left me ignorant of how his life was passing, and it seemed to me he had no right to impose the care of his daughter upon me, just because I had once tried to be good to him and he had once seemed to love me. And I knew it would be hard for you and Moses, too. We're all old together; and to rear another child—such an odd child, at that—I wonder, is it right?"

Now it so chanced that old Susanna had been entirely won by the manner in which Kate had chosen to be undressed and tended by the servant rather than the statelier mistress. Also, in the old days when "Johnny" had been with them, though the aunt had loved she had, also, reproved him; but childless Susanna, whose own little son had died, simply loved and never reproved. She now answered, promptly:

"Yes, Eunice Maitland, it's as right as right. She wouldn't have been sent if she hadn't been meant, would she? And she's the cut an' dried image of her own pa, bless him. Send her off? Course you'll do nothin' o' the kind. If you do, I'll leave, an' you can get somebody else to take[Pg 63] my place. So there, that's my say-so, an' you're welcome to it."

At the thought of Katharine's mobile little face being a "cut and dried image" of anybody Miss Eunice smiled, and her perplexity vanished—for the time, at least. Then, hearing the kitchen door unclose, she remarked:

"Well, I hear Moses coming in, and we three old people must get to rest. I am surely obliged to you for the help and comfort you are to me, Susanna, and to Moses, too. We'll do the best we can, and day by day."

"Certain, Eunice. That's the way to live, an' all's well 'at ends well, as we hope she will—this little orphant thrust upon us without no druther of our own, an' a bad beginnin' gen'ally makes a good ending; an' I 'low I'd best take one more peek into the sittin'-room chamber, afore I go to bed myself. Good night. Don't worry. I've fixed fish-cakes for breakfast."

With which comforting assurance for the morrow, the Widow Sprigg took herself out of the room, and quiet fell upon the old home.

"May I help? I think I could do that. It doesn't look hard," said Katharine, wandering into the kitchen where Susanna was seeding raisins—more raisins than the girl had ever seen together, save at a grocer's counter. "What are you doing it for?"

"Fruit-cake. For Thanksgivin' an' Christmas. I ought to of done it long ago, but the weather kep' so warm, an' one thing another's hendered. I'm all behind with everything this fall, seems if. I've got to make my soft soap yet, and—Laws, child, what do you lug that humbly dog all round with you for? A beast as ugly favored as he is ought to do his own walkin', and would, if he belonged to me."

"That's just why, I suppose. Because he 'belongs.' And because he isn't old. Not so very. He isn't gray, anyway."

The Widow Sprigg looked over her spectacles and saw such a dejected face that she immediately[Pg 65] suggested caraway cookies. A delicacy which had used to bring smiles to "Johnny's" countenance, even after he had suffered that worst of all boyish trials,—a "lickin',"—and if there was anything in heredity should restore cheer to the heart of "Johnny's" daughter.

"No, thank you. But I'd like to help. I shall—shall burst if I don't do something mighty soon," said Kate, excitedly. "I am hungry, but it's for folks, not cookies. And why do you make cake for Christmas now when it's forever and ever before it will come?"

"'Tain't so much for Christmas. Marsden folks don't set no great store by any other holiday than Thanksgivin'. Another why is that fruit-cake ain't fit to put in a body's mouth afore it's six seven months old at the least. This here won't be worth shucks, but Eunice says better late 'n never, an' if it ain't ripe then t'will be for Easter. We never used to hear tell of Easter, here in Marsden, till late years. Though Madam, she always kep' it. She's met with a change of heart, however, sence she became a Sturtevant, an' I'd ruther you wouldn't mention it, as comin' from me, but—" here Susanna leaned forward and whispered, sibilantly—"they say she used to be a Catholic when she was a girl! Nobody lays it up ag'in her, an' folks pertend they've forgot it; and if there is a good Christian goin', I 'low it's Madam Elinor Sturtevant. Your Aunt[Pg 66] Eunice—though she ain't your real aunt at all, only third cousin once removed—she was promised to Schuyler Sturtevant, Madam's husband's brother, but he was killed out on a fox-hunt, an' she ain't never married nobody sence. That's one why she an' Madam are such good friends, most like sisters; as they would have been hadn't things turned out different. But there, my suz! Don't stan' there lookin' so wishful. Put the dog in the lean-to an' shut the door. There's a strong air comes through it an' I feel it, settin' still. Then you can tie my check apern over your white frock. Don't you never wear no other kind of clothes, Katy? 'Cause I don't know who'll do your washin' an' ironin', if you don't."

Having finished a certain portion of the raisins, Susanna rose, washed her hands and tied the apron around Katharine's neck, bringing the strings forward under the arms with such firmness that the band choked the girl, and made a puffy blouse of the gingham. The whole arrangement was so uncomfortable that it was promptly taken off and hung upon its nail.

"I can't endure that, you know. If I must wear an apron, like a coon, I'll have one that fits. Why do I need it, anyway? This dress is only white piqué, and wears like iron. I heard stepmother say so when she gave it to the dressmaker. She never bought me anything but piqués and ducks and things that would stand[Pg 67] wearing without tearing. I mean—May I do this many?"

Susanna fairly snatched the dish away and shook her helper's fingers free from the cluster of raisins she had lifted, exclaiming:

"Why, I am surprised at you, Katharine Maitland! You takin' a bath every mornin', in cold water, too, an' keepin' yourself so tidy all the time, to go an' stun raisins after handlin' a dog! Wash 'em, an' clean your nails with this pin, an' tie that apern back—loose if you want—but wear it you must, or I won't be responsible for no smutch you get on you. Here's your basin for the hull ones; an' here's an earthen bowl for them 'at's done, an' a penknife to do 'em with. I declare! It's more work to get you ready to 'help' than 'twould be to do it all myself."

Katharine's spirits rose. Though she blushed at the reprimand for untidiness, a kind of reproof she seldom deserved, she was so accustomed to corrections that she scarcely listened to any, and sprang to a seat on the end of the great table with an outburst of rollicking "rag-time" song.

Safe to say that that sort of music had never before been heard within the dignified walls of that old mansion, and though Susanna was delighted to see "Johnny's girl" happy again, she was, also, somewhat shocked.

"Why—why, Katy! What's that you're saying? Don't sound like reg'lar English. Not[Pg 68] like 'Old Lang Syne,' nor 'The Old Oaken Bucket,' nor 'Send Round the Bowl,'—nor—My suz, child! What be you doin'?"

"Just, 'Sendin' Round the Bowl,' since you like it!" cried Kate, hilariously spinning the receptacle which had been given her for the "stunned raisins" across the table to where Susanna sat; then adding, mischievously, "And that's the first time that I knew that 'Old Lang Syne' was good English; I thought it was Scotch. As for 'rag-time,' all papa's friends said I could do it excellently well. You see, I was brought up with the coons and can mimic them easily. And you should see me do a cake-walk. I will after I've helped you awhile."

Susanna looked rather foolish at being herself set right. She had never aspired to much literary knowledge, but she did know that the words Katharine had sung were senseless, though they might sound funny. To cover her annoyance she demanded, rather crisply:

"What do you mean by 'coon' and 'duck'? Your pa always had odd notions, but I never 'lowed his daughter'd be raised with coons and ducks and animals of that natur'. I give him credit for some sense, even if he did paint pictures for a living."

Katharine's eyes flashed, then softened till they were on the verge of tears, and she announced with a finality that brooked no contradiction:[Pg 69]

"My father was the sensiblest, cleverest, dearest gentleman that ever lived. If I didn't come 'up' as I was 'brought' it wasn't his fault. And I'd rather not talk about him—not yet. Not to-day. 'Coons' are the colored people. Baltimore's full of them. They're our servants. Stepmother says they're worthless, nowadays, and I know she was always changing them. But they're the only kind we have down there. We couldn't get nice white ones like you. Why—what's the matter?"

The Widow Sprigg had risen very suddenly. Her face had flushed and a glitter come into the eyes behind the big spectacles, while her lips had closed with a sort of cluck. Leaning across the table, she demanded:

"Give me that bowl, please. I don't need no more your help."

Katharine extended the bowl, as desired, her own face clouding again at sight of the other's darkened one. And she fairly jumped as the housekeeper asked:

"Where's the raisins?"

"Oh! the raisins? Why—I hadn't begun yet. I ate the few I seeded. I'll begin now. I can work right smart if I try."

"Huh! go clean yourself an' clear out. I like to have my kitchen to myself."

Kate leaped from the table, having that odd homesickness stealing over her again, and as much[Pg 70] to dispel her own gloom as to keep her word, which she never broke if she could possibly help it, she cake-walked down the long kitchen with the gravest of faces and the most ludicrous of gestures. Down and back, down and back, head thrown sidewise over her shoulder, body bent at an angle which threatened a tumble backwards, and her feet alternately tossing the engulfing apron high on this side, then on that, and now become utterly oblivious of Susanna in her earnestness to distinguish herself—the girl seemed the absurdest creature it had ever been the housekeeper's lot to see.

She still felt insulted by Katharine's term of "servant," but could not repress a smile, and turned into the pantry to hide that telltale weakness.

Looking in through that same pantry window, his mouth agape, his eyes twinkling, was her housemate and natural enemy, Moses. Hitherto he had taken slight notice of the small new member of the household, and Kate had been rather afraid of him. It would, therefore, be killing two birds with one stone, or punishing two annoying people at one time, to pair them off together, thought Susanna, remarking:

"Well, Mr. Jones, when you get done staring at the monkey-shines of that young one you can just take her in charge a spell. Goin' to the wood-lot, ain't ye?"[Pg 71]

"You know I be. Said so at breakfast, didn't I? Silly women always do have to have idees druv into their heads, like nails, 'fore they can clinch 'em. Eunice 'lowed that we'd ought to have a lot more small sticks chopped," answered the man who managed the estate but was presumably managed himself by Miss Maitland. He had his axe over his shoulder, and had merely stopped at the pantry window, kept open for his benefit, to take a drink from the pail of buttermilk which stood there.

"Well, Eunice has gone down to Madam's. And I've no time to bother, and you'll have to take her 'long with ye. If she ain't under somebody's eye no tellin' what'll happen. Harm of some kind, sure's you're born."

Moses was about to retort and decline, but a second glance at the child, who had now finished her cake-walk and was listening to her elders, reminded him that, as yet, he had heard no details of that night's escapade when his beloved Monty had so wonderfully come out safe from peril of death. This had been some days before, and rumor had it that the lad was still confined a prisoner in his chamber. Whether because of real illness or for punishment, nobody knew, nor dared anybody question the dignified Madam. Eunice had heard the rumor that morning and had immediately gone to see her friend and offer her own service as nurse, should nursing be necessary.[Pg 72] Therefore, it was more to please himself than oblige Susanna, that he called through the window:

"Sissy, do you like chestnuts?"

"Oh, I love them! Why? And please, please don't call me 'Sissy.' It makes me feel so silly. My name is Katharine Maitland, though at home—" there came a little catch in her throat, which nobody else observed—"they used to call me 'Kitty Quixote,'" answered the girl, running to the window, and looking through the half-closed blind to the hired man.

"Hm-m. Ke-ho-ta. Kehota? Kee-ho-tee? Why, I thought I knew the Maitland family, root an' branch, twists an' turns an' ramifications, but I never heerd tell of a Keehotey amongst 'em. Not even 'mongst their wives' folks, nuther. Your own ma was a Woodley, and your pa's second was a Snowball, Eunice says, so how happens—"