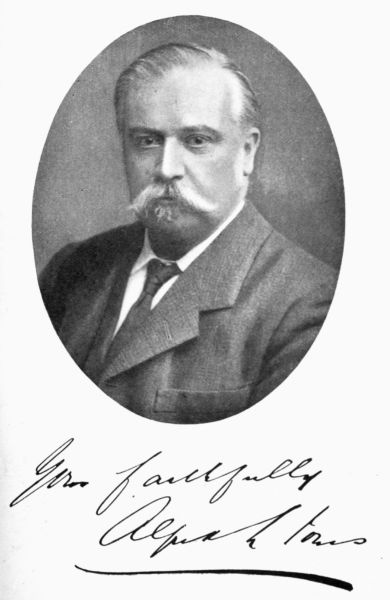

[Frontispiece.

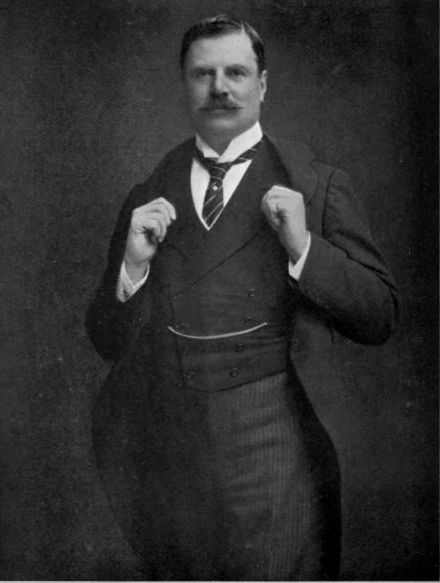

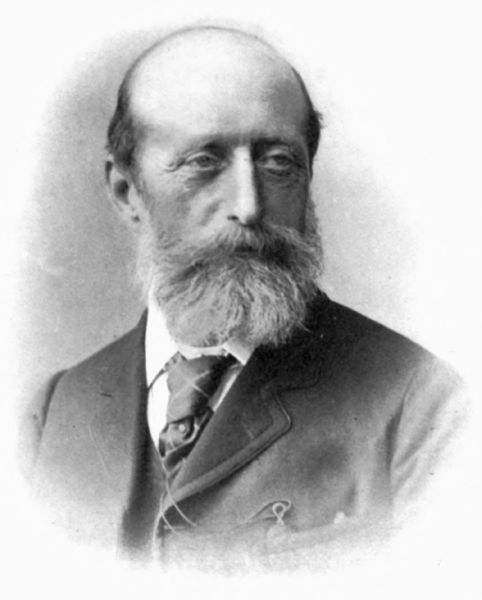

[Frontispiece.THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P.

(Postmaster-General.)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The King's Post, by R. C. Tombs This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The King's Post Author: R. C. Tombs Release Date: April 7, 2009 [EBook #28533] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE KING'S POST *** Produced by Adrian Mastronardi, Jane Hyland, The Philatelic Digital Library Project at http://www.tpdlp.net and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

[Frontispiece.

[Frontispiece.

Being a volume of historical facts relating to

the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach Roads,

and Railway Mail Services of and

connected with the Ancient

City of Bristol from 1580

to the present

time.

Ex-Controller of the London Postal Service, and late

Surveyor-Postmaster of Bristol;

Author of "The London Postal Service of To-day"

"Visitors' Handbook to General Post Office, London"

"The Bristol Royal Mail."

Bristol

W.C. Hemmons, Publisher, St. Stephen Street.

1905

2nd Edit., 1906. Entered Stationers' Hall. [Pg iv-v]

TO

THE RIGHT HON. LORD STANLEY,

K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P.,

HIS MAJESTY'S POSTMASTER-GENERAL,

THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED

AS A TESTIMONY OF HIGH

APPRECIATION OF HIS DEVOTION

TO THE PUBLIC SERVICE AT

HOME AND ABROAD,

BY

HIS FAITHFUL SERVANT,

THE AUTHOR.

When in 1899 I published the "Bristol Royal Mail," I scarcely supposed that it would be practicable to gather further historical facts of local interest sufficient to admit of the compilation of a companion book to that work. Such, however, has been the case, and much additional information has been procured as regards the Mail Services of the District.

Perhaps, after all, that is not surprising as Bristol is a very ancient city, and was once the second place of importance in the kingdom, with necessary constant mail communication with London, the seat of Government.

I am, therefore, enabled to introduce to notice "The King's Post," with the hope that it will[Pg viii] prove interesting and find public support equal to that generously afforded to its forerunner, which treated of Mail and Post Office topics from earliest times.

I have been rendered very material assistance in my researches by Mr. J.A. Housden, late of the Savings Bank Department, G.P.O., London; also by Mr. L.C. Kerans, ex-postmaster of Bath, and Messrs. S.I. Toleman and G.E. Chambers, ex-assistant Superintendents of the Bristol Post Office.

I have gathered many interesting facts from "Stage Coach and Mail," by Mr. C.G. Harper, to whom I express hearty indebtedness; and I am also under deep obligation to Mr. Edward Bennett, Editor of the "St. Martin's-le-Grand Magazine," and the Assistant Editor, Mr. Hatswell, for much valuable assistance.

R.C.T.

Bristol, September, 1905.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Earliest Bristol Posts, 1580.—Foot and Running Posts. —The First Bristol Postmasters: Allen and Teague, 1644-1660.—The Post House.—Earliest Letters, 1662. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Post House at the Dolphin Inn, in Dolphin Street, Bristol, 1662.— Exchange Avenue and Small Street Post Offices, Bristol. | 8 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Elizabethan Post to Bristol.—The Queen's Progress, 1574. | 16 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Roads.—The Coach.—Mr. John Palmer's Mail Coach Innovations, 1660-1818. | 22 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Appreciations of Ralph Allen, John Palmer, and Sir Francis Freeling, Mail and Coach Administrators. | 45 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Bristol Mail Coach Announcements, 1802, 1830.—The New General Post Office, London. | 62 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Bristol and Portsmouth Mail from 1772 onwards.—Projected South Coast Railway from Bristol, 1903.—The Bristol to Salisbury Postboy held up.—Mail Coach Accidents.— Luke Kent and Richard Griffiths, the Mail Guards. | 75 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Bush Tavern, Bristol's Famous Coaching Inn, and John Weeks, its worthy Boniface, 1775-1819.—The White Lion Coaching House, Bristol, Isaac Niblett.—The White Hart, Bath. | 93 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Toll Gates and Gate Keepers. | 110 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Daring Robberies of the Bristol Mail by Highwaymen, 1726-1781.—Bill Nash, Mail Coach Robber, Convict, and Rich Colonist, 1832.—Burglaries at Post Offices in London and Bristol, 1881-1901. | 119 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Manchester and Liverpool Mails.—From Coach to Rail.—The Western Railroad.—Post Office Arbitration Case. | 141 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Primitive Post Office.—Fifth Clause Posts.—Mail Cart in a Rhine. —Effect of Gales on Post and Telegraph Service. | 151 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Bristol Rejuvenated.—Visit of Prince of Wales in connection with the New Bristol Dock.—Bristol-Jamaican Mail Service.—American Mails.—Bristol Ship Letter Mails.—The Redland Post Office. —The Medical Officer.—Bristol Telegraphists in the South African War.—Lord Stanley, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P. —Mr. J. Paul Bush, C.M.G. | 160 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Small (The Post Office) Street, Bristol: its Ancient History, Influential Residents, Historic Houses; The Canns; The Early Home of the Elton Family. | 175 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The Post Office Trunk Telephone System at Bristol. | 195 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Post Office Benevolent Society: its Annual Meeting at Bristol.—Post Office Sports: Terrible Motor Cycle Accident.—Bristol Post Office in Darkness. | 199 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

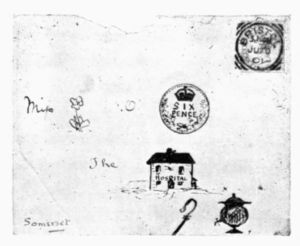

| Quaint Addresses.—The Dean's Peculiar Signature.—Amusing Incidents and the Postman's Knock.—Humorous Applications. | 223 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

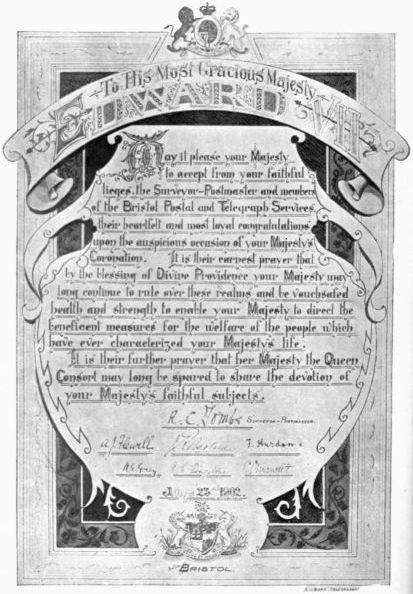

| Postmasters-General (Rt. Hon. A. Morley and the Marquis of Londonderry) Visit Bristol.—The Postmaster of the House of Commons.—The King's New Postage Stamps.—Coronation of King Edward VII.—Loyalty of Post Office Staff.—Mrs. Varnam-Coggan's Coronation Poem. | 232 |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

| 1. The Rt. Hon. Lord Stanley, K.C.V.O., C.B., M.P. | Frontispiece. |

| 2. The Old Post House in Dolphin Street, Bristol | 7 |

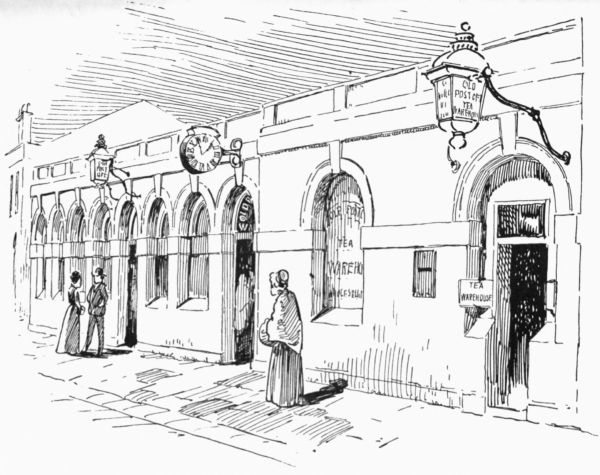

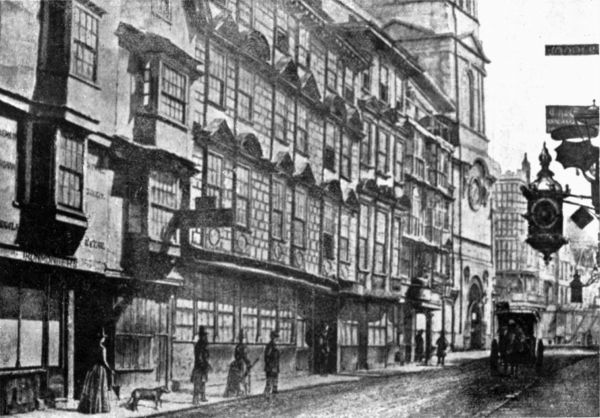

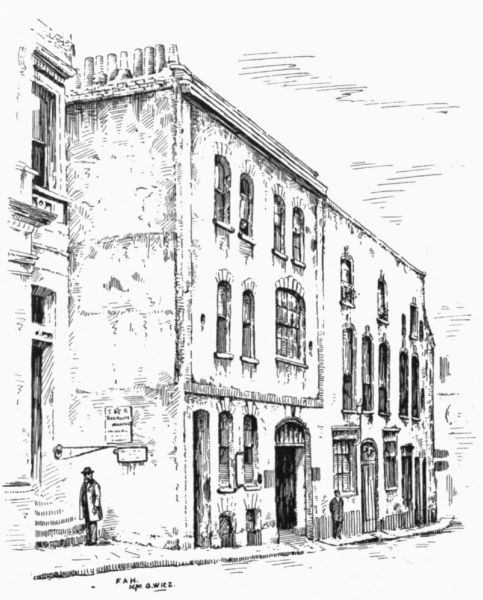

| 3. The Bristol Post Office, 1750-1868 | 9 |

| 4. The Bristol Post Office as enlarged in 1889 | 15 |

| 5. A State Coach of the period of King Charles I. | 23 |

| 6. The Bath and Bristol Waggon | 25 |

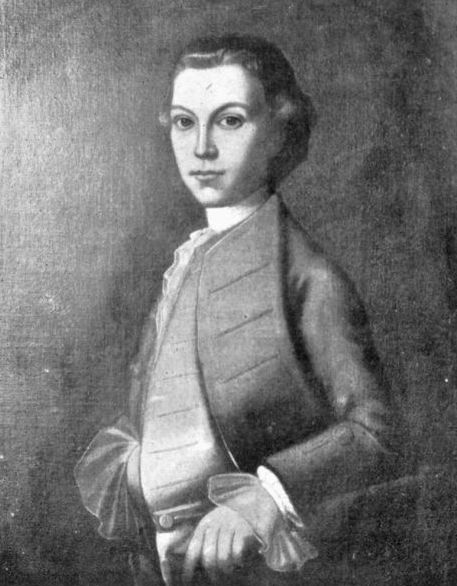

| 7. John Palmer at the age of 17 | 27 |

| 8. The Old Letter Woman | 29 |

| 9. The Old General Post Office in Lombard Street, London | 31 |

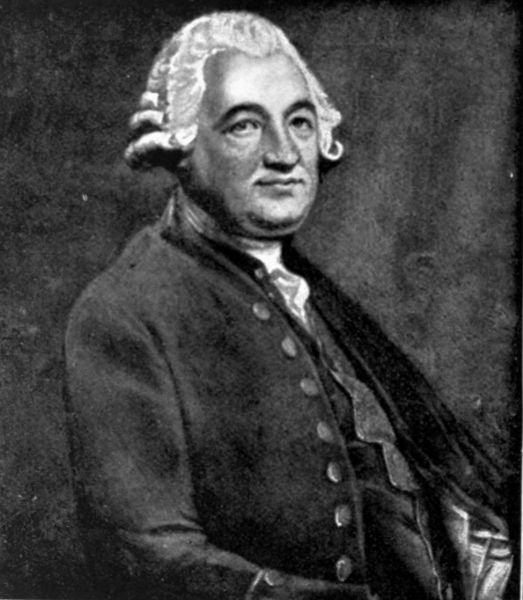

| 10. Anthony Todd | 35 |

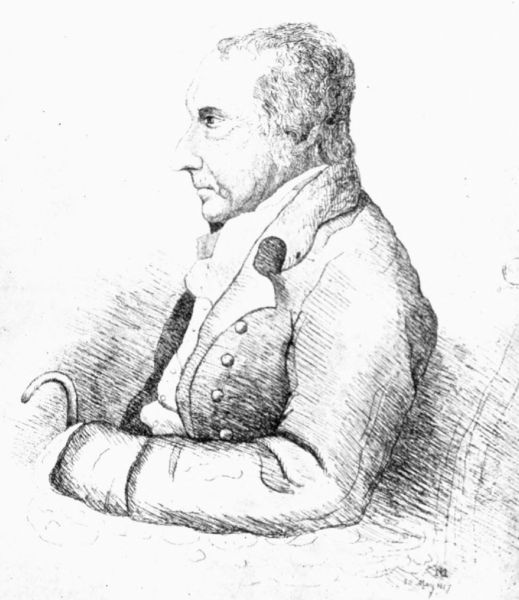

| 11. John Palmer at the age of 75 | 44 |

| 12. Medal Struck in honour of Ralph Allen | 49 |

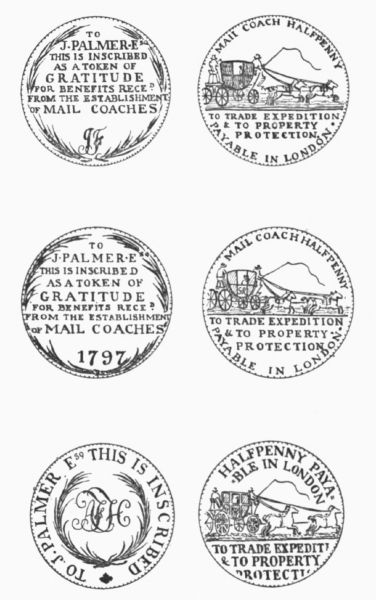

| 13. Mail Coach Tokens | 51 |

| 14. Birthplace of Sir Francis Freeling | 53 |

| 15. The Old Bristol Post Office in Exchange Avenue | 60 |

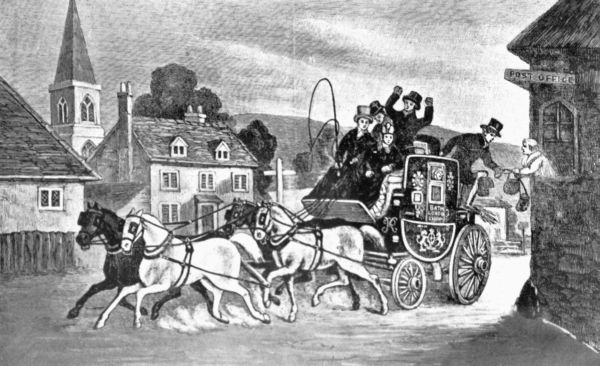

| 16. How the Mails were conveyed to Bristol in the days of King George IV. | 69 |

| 17. The Bristol and London Coach taking up Mails without halting | 72 |

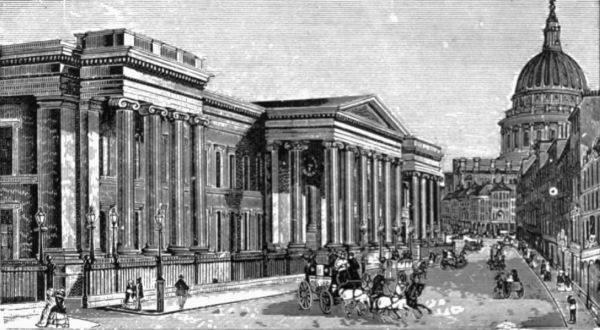

| 18. The General Post Office, London, in 1830 | 74 |

| 19. Mail Coach Guard's Post Horn | 90 |

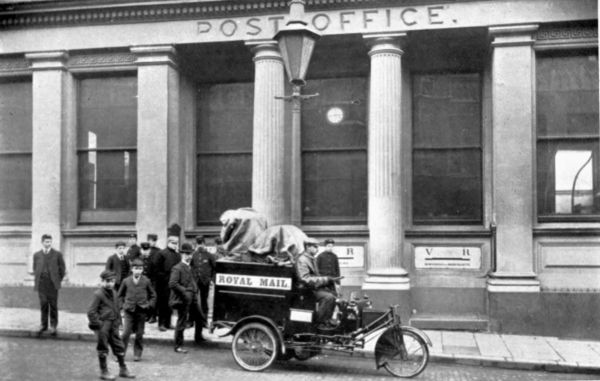

| 20. Avon Trimobile Motor Van | 92 |

| 21. Mural Tablet to John Weeks | 95 |

| 22. The Old White Lion Coaching Inn, Broad Street, Bristol | 107 |

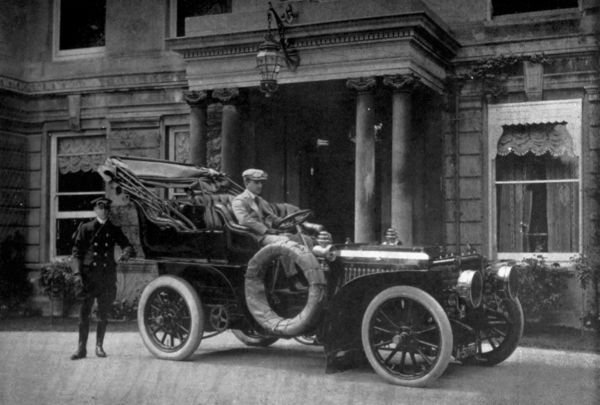

| 23. Mr. Stanley White's Coach | 108 |

| 24. Mr. Stanley White's Motor Car | 108 |

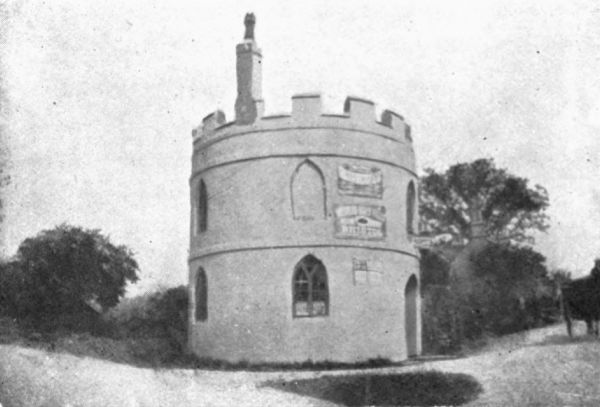

| 25. Bagstone Turnpike House | 111 |

| 26. Charfield Turnpike House | 112 |

| 27. Wickwar Road Turnpike House | 114 |

| 28. Wotton-under-Edge Turnpike House | 116 |

| 29. St. Michael's Hill Turnpike House | 117 |

| 30. Stanton Drew Turnpike House | 119 |

| 31. The White Hart Coaching Inn, Bath | 132 |

| 32. Old Post Office, Westbury-on-Trym | 136 |

| 33. Primitive Great Western Railway Train | 143 |

| 34. Bristol and Exeter Train, 1844 | 145 |

| 35. Great Western Railway Engine: "La France" | 148 |

| 36. Horton Thatched Post Office | 152 |

| 37. Early Bristol Post Marks | 154 |

| 38. Sir Alfred Jones, K.C.M.G. | 160 |

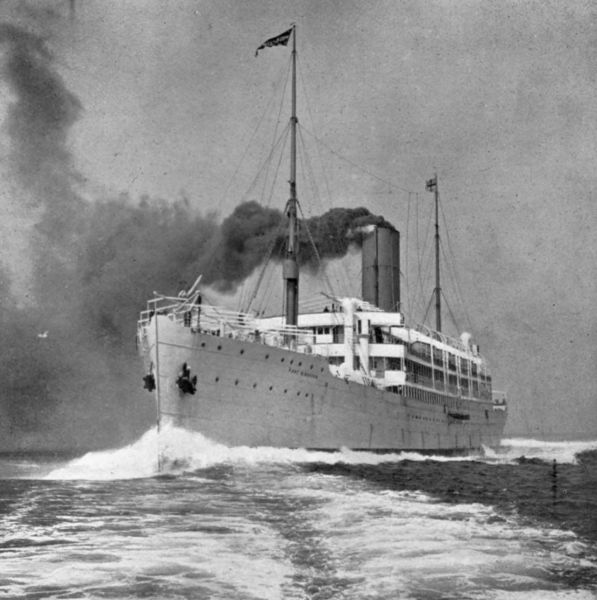

| 39. The "Port Kingston" | 161 |

| 40. The "Port Royal" | 162 |

| 41. Mr. F.P. Lansdown | 171 |

| 42. Mr. J. Paul Bush, C.M.G. | 174 |

| 43. Elton Mansion | 177 |

| 44. Sir Abraham Elton | 184 |

| 45. Lady Elton | 185 |

| 46. Gargoyle in Elton Mansion | 188 |

| 47. Ancient Chimney-piece | 191 |

| 48. Edward Colston | 192 |

| 49. Charles II. | 193 |

| 50. King Charles, Flight of | 194 |

| 51. Columbia Stamping Machine | 198 |

| 52. Postmaster of Bristol (The Author) | 211 |

| 53. Quaintly Addressed Envelopes | 224 |

| 54. Prudent Man's Fund Receipt Note | 231 |

| 55. Address to the King | 241 |

THE EARLIEST BRISTOL POSTS, 1580.—FOOT AND RUNNING POSTS.—THE FIRST BRISTOL POSTMASTERS: ALLEN AND TEAGUE, 1644-1660.—THE POST HOUSE.—EARLIEST LETTERS, 1662.

The difficulty in Queen Elizabeth's time of communicating with persons at a distance from Bristol before the establishment of a post office is illustrated by the following item from the City Chamberlain's accounts:—

"1580, August. Paid to Savage, the foot post, to go to Wellington with a letter to the Recorder touching the holding of the Sessions, and if not there to go to Wimborne Minster, where he has a house, where he found him, and returned with a letter; which post was six days upon that journey in very foul weather, and I paid him for his pains 13s. 4d."

The next record of a person performing postman's work in Bristol is that of 1615, when the[Pg 2] City Chamberlain paid a tradesman 12s. "for cloth to make Packer, the foot post, a coat." In 1616, Packer was sent by the same official to Brewham to collect rents, and was paid 3s. 8d. for a journey, out and home, of 60 miles. This system of a foot post to collect money in King James the First's reign appears to be an early application of the somewhat analogous plan, which of recent years has been under departmental consideration as "C.O.D.," or collection of business and trade charges by the postman on delivery of parcels—an exemplification of there being nothing new under the sun!

That travelling and the conveyance of letters was difficult in 1626 is evident from the fact that nearly £60 was spent in setting up wooden posts along the highway and causeway at Kingswood, for the guidance of travellers, the tracks being then unenclosed, so that the "foot post" must have had no enviable task on his journeys. In October, 1637, John Freeman was appointed "thorough post" at Bristol, and ordered to provide horses for all men riding post on the King's affairs of King Charles I: Letters were not to be[Pg 3] detained more than half a quarter of an hour, and the carriers were to run seven miles an hour in summer, and five in winter. A Government "running post" from London to Bristol and other towns was ordered on July 31st, 1638. No messengers were thenceforth to run to and from Bristol except those appointed by Thomas Withering, but letters were allowed to be sent by common carriers, or by private messengers passing between friends. The postage was fixed at twopence for under 80 miles, and at fourpence for under 140 miles.

In 1644 Lord Hopton "commanded" the grant of the freedom of Bristol to one Richard Allen, "Postmaster-General." In August, 1643, Lord Hopton was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of Bristol, and held that appointment until 1645, when Fairfax took the city. Probably Allen was Postmaster-General of Bristol, and his authority may have extended to other parts of the country that were held by the King's forces. Prideaux was appointed Master of the Posts by Parliament, and his jurisdiction extended as far as the country was under the control of Parliament, as distinguished from such parts of England as adhered[Pg 4] to the King. In 1644, however, very few places—Bristol was one of them—still adhered to Charles. At an earlier stage of the civil war special posts had been arranged for the King's service, and it is thought Bristol was one of the places to which these special posts were arranged.

In the Calendar of State Papers, under the year 1660, there is a complaint against one "Teig," an anabaptist Postmaster of Bristol, who broke open letters directed to the King's friends.

The complaint against him appears to have been very seriously considered by the authorities, and it induced his friends to take up the cudgels in his behalf as indicated by the following memorials:—

"To the Hon. John Weaver, Esq.: of the Council of State: Honoured Sir—Having so fit a Messenger I would not omit to acquaint you what a sad state and condition we are fallen into: How the good old cause is now sunke and a horrid spirit of Prophaneous Malignity and revenge is risen up Trampling on all those who have the face of godlinesse and have been of ye Parliamt party insoemuch that if the Lord doe not interpose I doubt a Mascare will follow."[Pg 5]

"Sir—I have a request to make in the behalfe of this Bearer Mr Teage who is an honest faithfull sober man That you would stead him what you can about his continuance in the Post Office for this Citty. I beleive it will be but for a short continuance for I beleive that few honnest men in England shall have any place of trust or profit. The Cavilears Threaten a rooting out all Suddamly Thus with the tender of my old love and reall respects to you I take leave and Rest Your most humble and obliged servant, Ja Powell Bristoll this 14th April 60."

"To the Right Honble the Comittee appointed by the Councill of State for the Management of the Poste affaire Whereas John Teage who hath formerly beene actually in Armes for ye Parliamt and since that being an Inhabitant of this Citty hath beene Postmaster here for many years last past He being a person well qualified and capable for such an imploiment We doe therefore humbly recomend him to your Honors to be continued in his said place And we doubt not of his faithfull management thereof

"Given under our hands at Bristoll this 14th

[Pg 6]day of Aprill 1660. Edwd. Tyson (?) Mayr.

Henry Gibbes Aldm Robert Yates Aldm

James Parsons Ch (?) Dooney George Lane,

Junior, J. Holwey Nehe Cotting

Andrew Hooke James Powell Richd Baugh

Tho. Deane Robert Hann

James Phelps (?) Abell Kelly."

(Two other names undecipherable.)

Having regard to the looseness of the spelling at that period, it is he, no doubt, who is mentioned later on as the "Mr. Teague" at the Dolphin, to whose care a Mr. Browne's letter was addressed in 1671. If Teig or Teague did continue at his post until 1671 he must have renounced his Anabaptist opinions and conformed, for no Postmaster was to remain in the service unless he was conformable to the discipline of the Church of England.

Evans mentions in his Chronological History, under 1663, a letter addressed: "To Mr. John Hellier, at his house in Corn Street, in Bristol Citty," from which it may be inferred that a postman was then employed for deliveries in the principal streets.

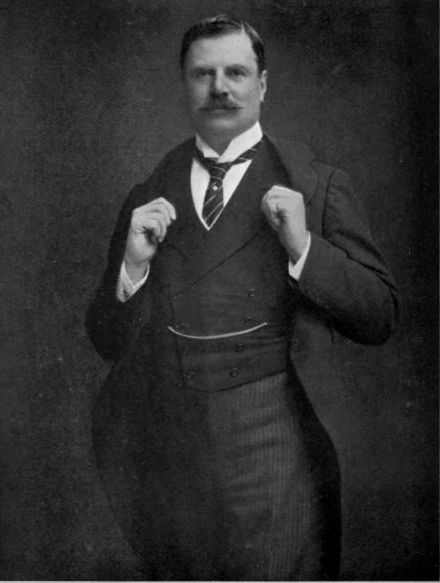

THE OLD POST-HOUSE IN DOLPHIN STREET, BRISTOL.

THE OLD POST-HOUSE IN DOLPHIN STREET, BRISTOL.

In the Broadmead Chapel Records (1648-1687), published in 1847, and now in the Baptist College, there is mention, at page 126, of a letter of Mr. Robert Browne, "To my much revered brother, Mr. Terrill, at his house in Bristol. To be left with Mr. Mitchell, near the Post Office." The letter was dated Worcester, 15 d. 1 m. 1670-1, and signed Robert Browne, with this foot-note, "I am forced to send now by way of London." A second letter of Mr. Browne, sent in April, 1671, is mentioned likewise. It is addressed "To my respected friend Mr. Terrill, at his house in Bristol. To be left with Mr. Teague at the Dolphin, in Bristol," and begins "My dear Brother, I hope you have receeived both mine, that one sent by the way of London, the other by the trow from Worcester."

THE POST HOUSE AT THE DOLPHIN INN, IN DOLPHIN STREET, BRISTOL, 1662.—EXCHANGE AVENUE AND SMALL STREET POST OFFICES, BRISTOL.

That a Bristol Post-house existed early in the reign of King Charles II. is indicated by a letter preserved at the Bristol Museum Library, which was sent in August of 1662 from Oxford, and is addressed: "This to be left at the Post-house in Bristol for my honoured landlord, Thomas Gore, Esquire, living at Barrow in Somerset. Post paid to London."

The Dolphin Inn was for several years—even down to 1700—the Bristol Post-house, and it was there that the postboys stabled their horses. The inn long afterwards gave its name to Dolphin Street, which the street still retains. It is believed the inn stood near the low buildings with large gateway, in Dolphin Street, shown in the illustration. These premises at the time the picture[Pg 9] was drawn, in about 1815, had become the stables of the Bush Inn in Corn Street, long celebrated as Bristol's most famous coaching inn. The site has, until quite recently, been used in connection with the carrying business.

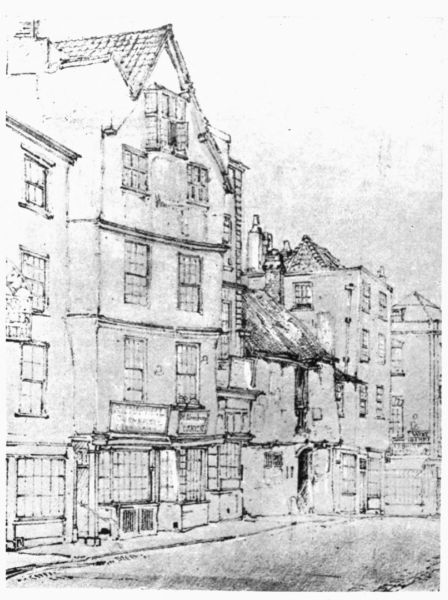

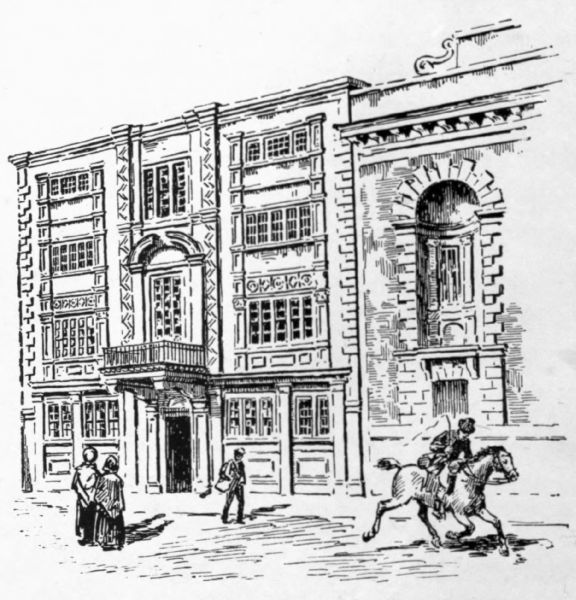

THE BRISTOL POST OFFICE, 1750-1868.

THE BRISTOL POST OFFICE, 1750-1868.

In 1700 the first actual Post Office was built. It was erected in All Saints' Lane, and was held by one Henry Pine, as Postmaster. This Post Office served the city's purpose until 1742, when the site was required in connection with the building of the Exchange, and the Post Office was transferred to Small Street. In September of that year (1742), an advertisement describes the best boarding school for boys in Bristol as being kept in Small Street by Mr. John Jones, in rooms "over the Post-house." What kind of building this was is uncertain, as there is no picture of it obtainable. Indeed, the first traceable illustration of a Bristol Post Office is the engraving, a copy of which is here reproduced, depicting the building erected in 1750, at the corner of the Exchange Avenue as it appeared in 1805, when it was described as "a handsome freestone building, situated on the west side of the Exchange,[Pg 10] to which it forms a side wing, projecting some feet forward in the street; on the east side being another building answerable thereto." These premises served as the Post Office for the long period of 118 years.

The first half of the present Bristol Post Office premises in Small Street was occupied by Messrs. Freeman and Brass and Copper Company.

As a matter of history, a copy of the abstract of conveyance may, perhaps, be fittingly introduced. It sets forth the particulars of the uses to which the site was originally put before taken by the Post Office.

"21st December, 1865.—By Indenture between the Bristol City Chambers Company, Limited, (thereinafter called the Company) of the one part, and the Right Honourable Edward John Lord Stanley of Alderley, Her Majesty's Postmaster General for the time being, of the other part

"It is witnessed that in consideration of £8,000 paid by the said Postmaster General to the said Company the said Company did thereby grant and convey unto Her Majesty's Postmaster General his successors and assigns[Pg 11]—

"Firstly All that plot piece or parcel of ground situate in the Parish of St.-Werburgh in the City of Bristol on the South West side of and fronting to Small Street aforesaid specified in the plan drawn in the margin of the first Skin of abstracting Indenture said piece of land being therein distinguished by an edging of red color which said plot of ground formed the site of a certain messuage warehouses and buildings recently pulled down which said premises were in certain Deeds dated 13th February, 1861, described as 'All that messuage or Warehouse situate on the South West side of and fronting to Small Street in the City of Bristol then lately in the occupation of Messrs. Turpin & Langdon Book Binders but then void and also all those Warehouses Counting-house Rooms Yard and Buildings situate lying and being behind and adjoining to the said last named messuage or Warehouse and then and for some time past in the occupation of Messrs. John Freeman and Copper Company and used by them for the purposes of their Co-partnership trade and business.' Secondly, All that plot piece or parcel of ground adjoining the heredits firstly thereinbefore[Pg 12] described on the North West side thereof and also fronting to Small Street aforesaid and specified on the said plan and therein distinguished by an edging of blue color which said plot of ground formed the site of certain premises also then recently pulled down which said premises were in certain Deeds dated 13th February 1861 described as "All that messuage or dwelling-house formerly in the holding of Thomas Edwards Linen Draper since that of William Lewis Tailor afterwards and for many years of John Powell Rich then of George Smith as Tenants to Messrs. Bright & Daniel afterwards of Daniel George but then unoccupied situate and being No. 6 in Small Street in the Parish of St.-Werburgh in the City of Bristol between a messuage or tenement formerly in the possession of Messrs. Harford & Coy. Iron Merchants but then of the Bristol Water Works Company on or towards the north part and a Coach-house yard and premises then formerly in the occupation of Richard Bright and Thomas Daniel and then Co-partners trading under the Firm of the Bristol Copper Company but then the property of the said James Ford on[Pg 13] the South part and extending from said Street called Small Street on the East part backward to the West unto part of the ground built on by the said Copper Company the Wall between the Warehouse and said messuage."

When, in the year 1867, the plan for this new Post Office building in Small Street had been prepared and Treasury authority obtained for the expenditure of a sum of £8,000 in the erection of the building, the Inland Revenue Department asked for accommodation in the structure, and it was arranged that its staff should be lodged on the first floor of the new building. The building itself had, therefore, to be carried to a greater height than had originally been contemplated. This alteration cost £3,000. There is still evidence in the building of the occupation of the Inland Revenue staff, iron gates and spiked barriers in the first floor passage to cut off their rooms from the Post Office section still remaining.

The authorities of the Post Office accepted tenders in September, 1887, for the demolition of certain premises known as "New Buildings" and for the erection thereon of additional premises[Pg 14] for the accommodation of the growing Postal staff. The work began on the 26th September. The cost of the new wing was estimated at £16,000. Beneath the superstructure there were two tiers of ancient cellars, one below the other, forming part of the original mediæval mansion once owned by the Creswick family; and the removal of these was attended with much difficulty. The new building was opened for business on the 4th November, 1889.

In Parliament. Session 1903. Post Office (Acquisition of Sites) Power to the Postmaster-General to acquire Lands, Houses, and Buildings in Bristol for the service of the Post Office. Notice is hereby given that application is intended to be made to Parliament in the next session for an Act for the following purposes or some of them (that is to say):—To empower His Majesty's Postmaster-General (hereinafter called 'the Postmaster-General') to acquire for the service of the Post Office, by compulsory purchase or otherwise, the lands, houses, and buildings hereinafter described, that is to say:—

"Bristol: (Extension of Head Post Office).[Pg 15] Certain lands, houses, offices, buildings and premises situate in the parish of St. Werburgh, in the city and county of Bristol, in the county of Gloucester, and lying on the south-west side of Small Street, and the east side of St. Leonards Lane."

[By permission of "The Bristol Observer."

[By permission of "The Bristol Observer."Thus commenced a portentous notice which appeared in a Bristol newspaper, and had reference to the Bristol Water Works premises being acquired for the further enlargement of the Post Office buildings.

The superficial area of the ground on which the Bristol Post Office stands is a little over 17,000 square feet. The new site joins the present Post Office structure, and has a frontage of 88 feet to Small Street. Its area is 11,715 superficial feet, so that the enlargement will be considerable but by no means excessive, having regard to the extremely rapid development of the Bristol Post Office business.

ELIZABETHAN POST TO BRISTOL.—THE QUEEN'S PROGRESS, 1574.

Particulars are on record respecting a very early Post from the Court of Queen Elizabeth to Bristol. At that period it occupied more days for the Monarch to travel in Sovereign State to Bristol than it does hours in these days of Great Western "fliers." It seems that Queen Elizabeth made a Progress to Bristol in 1574. She travelled from London by way of Woodstock and Berkeley. She arrived at Bristol, August 14, 1574, and had a splendid and elaborate reception:—

"Before the Queen left Bristol she knighted her host, John Young, who, in return for the honour done him, gave her a jewel containing rubies and diamonds, and ornamented with a Phœnix and Salamander. She did not get quit of the city until after she had listened to many weary verses[Pg 17] describing the tears and sorrows of the citizens at her departure, and their earnest prayer for her prosperity. From Bristol she travelled to Sir T. Thynne's, at Longleat, and from Longleat across Salisbury Plain to the Earl of Pembroke's, at Wilton, where she arrived September 3rd."

The British Museum records show that in 1580 Ireland was in rebellion. A Spanish-Italian force of eight hundred men had been sent, with at least the connivance of Philip II. of Spain, to assist the rebels, and the English Government was compelled to hurry reinforcements and supplies to Ireland. These reinforcements and supplies went by way of Bristol, and it was at that juncture of affairs that a post was established between London, or Richmond, where the Court was, and Bristol. This post, if not actually the first, was certainly one of the earliest posts to Bristol.

At a meeting of the Privy Council held September 26, 1580, a warrant was issued "to Robert Gascoigne for laying of post horses between London and Bristol, requiring Her Majesty's officers to be assisting unto him in this service."[Pg 18] A warrant was also issued "to Sir Thomas Heneage, Knight, Treasurer of her Majesty's Chamber, to pay unto Robert Gascoigne the sum of ten pounds to be employed about the service of laying post horses between London and Bristol."

The duty of laying this post was not entrusted to the Master of the Posts, Thomas Randolph, but to Gascoigne, the Postmaster of the Court, who usually arranged the posts rendered necessary by Queen Elizabeth's progresses through her dominions. Gascoigne afterwards furnished an account of what he had done to carry out the Order of the Privy Council, and from this document, which is preserved at the Record Office in London, it seems that the post travelled from Richmond, or London, to Hounslow, and thence to Maidenhead (16 miles), Newbury (21 miles), Marlborough (16 miles), Chippenham (22 miles), and thence to Bristol (20 miles). The cost of the post for a month of 28 days is stated to have been £14 9s.; but it does not appear if this amount is in addition to the £10 ordered to be paid to Gascoigne for laying the post; nor is there any[Pg 19]thing to show how often the post travelled, or for how long it was maintained; Gascoigne describes it as an "extraordinary" post. At that time the only ordinary posts were from London to Berwick, Holyhead, and Dover respectively. It is, perhaps, as well to add that these posts were the Queen's posts, and were only intended for the conveyance of persons travelling on her service or of packets sent on her business, though other persons used the posts for travelling and for sending letters.

Several complaints were made by Leonard Dutton and another against Robert Gascoigne, Postmaster of the Court, in respect of abuses connected with the posts thus laid down for Queen Elizabeth's use while on a "Progress." The complainants charged Gascoigne with neglect of duty, laying posts to suit his own convenience, delaying letters, making improper charges, and stopping something for himself out of money he should have paid in wages, etc. Among the papers relating to this affair is a copy of part of Gascoigne's account, of which the following is a transcript:—

THE OFFICE OF THE POSTE.

In the office of William Dodington, Esquire, Auditor of Her Matie. Impreste, in the bill of accompt for Her Matie poste among other things is contained the following:

"Robert Gascoigne's bill for the laying of the extraordinary post on Her Majesty's Progress.

"Bristoll.—Thomas Hoskins and a constable

entered post at Bristol for serving x. days begun

xiij. of August until the xxij. of the same month,

half days included, at ij.s. per diem.

"xx.s.

"Mangotsfield.—Philip Alsop and John

Alsop, post at Mangotsfield for serving v. days

begun the xviij. of August and ended the xxij.

of the same month, half days included, at ij.s.

per diem.

"x.s.

"Chippenham.—John Barnby and Leonard

Woodland entered post at Chippenham for serving

x. days begun the xviij. August and ended the

xxvij. of the same month, half days included at

ij.s. per diem.

"xx.s.

"Marlborough.—Thomas Pike and Anthony

Ditton entered post at Marlborough for serving[Pg 21]

xvij. days begun the xviij. August and ended

the third day of September, half days included

at ij.s. per diem.

"xxxiv.s.

"Exd. per me Barth. Dodington."

As to the Marlborough post, Anthony Ditton was Mayor of the town, as appears from a certificate by him (which is with the papers) that he only received from Gascoigne 15s. for the posts. Gascoigne claimed to have paid at Marlborough 34s. (see the transcript of his account), and if Ditton was entitled to half that sum Gascoigne pocketed 4s. (£19 15s. 4d.). This is the sort of thing Ditton charged him with doing. To these charges Gascoigne gave a denial, separately explaining each charge. His explanation was accepted, inasmuch as he was continued in office.

THE ROADS.—THE COACH.—MR. JOHN PALMER'S MAIL COACH INNOVATIONS, 1660-1818.

In 1660-1661, James Hicks, Clerk to "The Roads" in the Letter Office, petitions the King to be continued in office. He says he sent the first letter from Nantwich to London in 1637, and was sent for in 1640 to be Clerk for that Road (Chester Road). Had settled in 1642 "Postages between BRISTOL and YORK for your late father's service."

In 1661, Henry Bisshopp, farmer of the Post Office, furnished to the Secretary of State "a perfect list" of all officers in the Post Office. According to this list there were eight Clerks of the Roads, viz.:—Two of the Northern Road, two of the Chester Road, two of the Eastern Road, and Two of the Western Road. In 1677, there were, in addition to these Roads, the Bristol Road and the Kent Road. As there was a [Pg 23]Post-House at Bristol in 1661, no doubt the city was attached to the Western Road.

[From an old print.

[From an old print.There were only six stage-coaches known in 1662. A journey that could not be performed on horseback was rarely undertaken then by those who could not afford their own steeds.

Amongst the State papers in May, 1666, is an account of the time spent in carrying the mails on the chief routes throughout the country. Although the speed fixed by the Government for the postboys was seven miles an hour in the summer months, the actual rate attained on the Bristol, Chester, and York Roads was only four miles, and was half-a-mile less on the Gloucester and Plymouth routes. An appended note stated that a man spent seventeen or eighteen hours in riding from Winchester to Southampton. In December, Lord Arlington complained to the postal authorities that the King's letters from Bristol and other towns were delayed from ten to fourteen hours beyond the proper time, and ordered that the Postmasters should be threatened with dismissal unless they reformed.

In 1667 a London and Oxford Coach was[Pg 24] performing the 54 miles between the two cities in two days, halting for the intervening night at Beaconsfield: and in the same year the original Bath Coach was the subject of this proclamation:

"Flying Machine."—"All those desirous of passing from London to Bath, or any other place on their Road, let them repair to the 'Belle Sauvage' on Ludgate Hill, in London, and the 'White Lion' at Bath, at both which places they may be received in a Stage Coach, every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, which performs the whole journey in Three Days (if God permit) and sets forth at 5 o'clock in the Morning.

"Passengers to pay One Pound Five Shillings each, who are allowed to carry fourteen Pounds Weight—for all above to pay three-halfpence per Pound."

It was only after repeated appeals to the Government that a "Cross Post" was established between Bristol and Exeter for inland letters in 1698, thus substituting a journey of under 80 miles for one of nearly 300, when the letters were carried through London. In this case, however, Bristol letters to and from Ireland were[Pg 25] excluded from the scheme, and they still had to pass through the Metropolis.

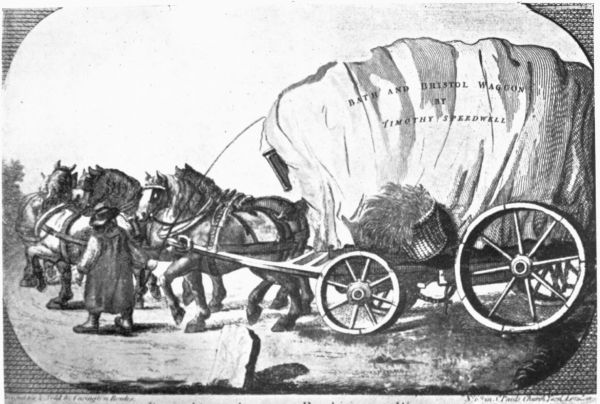

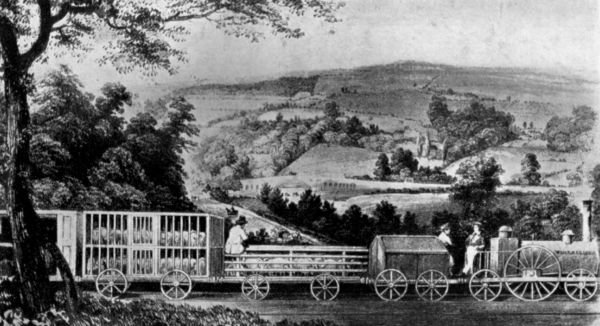

I've nothing to brag on But driving my Waggon. Temp: Georgius III.

I've nothing to brag on But driving my Waggon. Temp: Georgius III.

Even at a later date, when strong representations were made to the Post Office, Ralph Allen, of Bath, who had the control of the Western Mails, refused to allow a direct communication between Bristol and Ireland, but offered if the postage from Dublin to London were paid, to convey the letters to Bristol gratis.

At this period there were quaint public waggons on the Bristol Road, as depicted in the illustration.

The "Pack Horse" at Chippenham, and the "Old Pack Horse," and the "Pack Horse and Talbot," at Turnham Green, were, in 1739, halting places of the numerous Packmen who travelled on the Bristol and Western Road.

By 1742 a stage-coach left London at seven every morning, stayed for dinner at noon in Uxbridge, arrived at High Wycombe by four in the afternoon, and rested there all night, proceeding to Oxford the next day. Men were content to get to York in six days, and to Exeter in a fortnight.

In 1760, in consequence of frequent complaints[Pg 26] as to the dilatoriness of the postal service, the authorities in London announced that letters or packets would thenceforth be dispatched from the capital to the chief provincial towns "at any hour without loss of time," at certain specified rates. An express to Bristol was to cost £2 3s. 6d.; to Plymouth, £4 8s. 9d. Leeds, Manchester, Birmingham, Liverpool, were not even mentioned.

The mail-coach system had its origin in the West of England, and Bristol and Bath in particular are associated with all the traditions of the initiatory stages, so that the details on record in ancient newspapers of those cities are copious.

Mr. John Weeks, who entered upon "The Bush," Bristol, in 1772, after ineffectually urging the proprietors to quicken their speed, started a one-day coach to Birmingham himself, and carried it on against a bitter opposition, charging the passengers only 10s. 6d. and 8s. 6d. for inside and outside seats respectively, and giving each one of them a dinner and a pint of wine at Gloucester into the bargain. After two years' struggle, his opponents gave in, and one-day journeys to Birmingham became the established rule.

[From "Stage Coach and Mail," by permission

of Mr. C.G. Harper.

[From "Stage Coach and Mail," by permission

of Mr. C.G. Harper.Soon after this period, John Palmer, of Bath, came on the scene. He had learnt from the merchants of Bristol what a boon it would be if they could get their letters conveyed to London in fourteen or fifteen hours, instead of three days. John Palmer was lessee and manager of the Bath and Bristol theatres, and went about beating up actors, actresses, and companies in postchaises, and he thought letters should be carried at the same pace at which it was possible to travel in a chaise. He devised a scheme, and Pitt, the Prime Minister of the day, who warmly approved the idea, decided that the plan should have a trial, and that the first mail-coach should run between London and Bristol. On Saturday, July 31, 1784, an agreement was signed in connection with Palmer's scheme under which, in consideration of payment of 3d. a mile, five inn-holders—one belonging to London, one to Thatcham, one to Marlborough, and two to Bath—undertook to provide the horses, and on Monday, August 2, 1784, the first "mail-coach" started.

The following was the Post Office announcement respecting the service:—"General Post Office,[Pg 28] July 24, 1784. His Majesty's Postmaster-General being inclined to make an experiment for the more expeditious conveyance of the mails of letters by stage-coaches, machines, etc., have (sic) been pleased to order that a trial shall be made upon the road between London and Bristol, to commence at each place on Monday, August 2 next, and that the mails should be made up at this office every evening (Sundays excepted) at 7 o'clock, and at Bristol, in return, at 3 in the afternoon (Saturdays excepted), to contain the bags for the following post towns and their districts—viz.: Hounslow—between 9 and 10 at night from London; between 6 and 7 in the morning from Bristol. Maidenhead—between 11 and 12 at night from London; between 4 and 5 in the morning from Bristol. Reading—about 1 in the morning from London; between 2 and 3 in the morning from Bristol. Newbury—about 3 in the morning from London; between 12 and 1 at night from Bristol. Hungerford—between 4 and 5 in the morning from London; about 11 at night from Bristol. Marlborough—about 6 in the morning from London; between 9 and 10 at night from[Pg 29] Bristol. Chippenham—between 8 and 9 in the morning from London; about 7 in the evening from Bristol. Bath—between 10 and 11 in the morning from London; between 5 and 6 in the afternoon from Bristol. Bristol—about 12 at noon from London.

The Letter Woman.

The Letter Woman."All persons are therefore to take notice that the letters put into any receiving house in London before 6 in the evening, or before 7 at this office, will be forwarded by this new conveyance; all others for the said post-towns and their districts put in afterwards, or given to the bell-men, must remain until the following post, at the same hour of 7 o'clock. [At this period there were Post Office bell-women as well as bell-men. See illustration.]

"Letters also for Colnbrooke, Windsor, Calne, and Ramsbury will be forwarded by this conveyance every day; and for Devizes, Melksham, Trowbridge, and Bradford on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays; and for Henley, Nettlebed, Wallingford, Wells, Bridgwater, Taunton, Wellington, Tiverton, Frome, and Warminster, on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.[Pg 30]

"Letters from all the before-mentioned post-towns and their districts will be sorted and delivered as soon as possible after their arrival in London, and are not to wait for the general delivery.

"All carriers, coachmen, higglers, news carriers, and all other persons are liable to a penalty of £5 for every letter which they shall receive, take up, order, dispatch, carry, or deliver illegally; and to £100 for every week that any offender shall continue the practice—one-half to the informer. And that this revenue may not be injured by unlawful collections and conveyances, all persons acting contrary to the law therein will be proceeded against, and punished with the utmost severity.

"By command of the Postmaster-General,

"Anthony Todd, Sec."

The Bath Chronicle versions were as follows, viz.:—"July 29, 1784. On Monday next the experiment for the more expeditious conveyance of the mails will be made on the road from London to Bath and Bristol. Letters are to be put in the London office every evening before 8 o'clock, and to arrive next morning in Bath before 10 o'clock,[Pg 31] and in Bristol by 12 o'clock. The letters for London, or for any place between or beyond, to be put into the Bath Post Office every evening before 5 o'clock, and into the Bristol office before 3 o'clock in the afternoon, and they will be delivered in London the next day."

[By permission of Kelly's Directories, Lim.

[By permission of Kelly's Directories, Lim.The public were also informed that the mail diligence would commence to run on Monday, August 2, 1784—and that the proprietors had engaged to carry the mail to and from London to Bristol in sixteen hours, starting from the Swan with Two Necks, in Lad Lane, London, at 8 o'clock each night, and arriving at the Three Tuns, Bath, before 10 o'clock the next morning, and at the Rummer Tavern, Bristol, by 12 o'clock. "The mail is to leave Bristol from the Swan Tavern for London every afternoon at 4 o'clock, and to arrive in London before 8 o'clock the next morning."

On August 5, we are told, "the new mail diligence set off for the first time from Bristol on Monday last, at 4 o'clock, and from Bath at 5.20 p.m. From London it set out at 8 o'clock in the evening, and was in Bath by 9 o'clock the next morning.[Pg 32]

"The excellent steps taken to carry out this undertaking leave no doubt of its succeeding, to the great advantage and pleasure to the publick. The mail from this city is made up at 5 o'clock." This grand achievement of Palmer's was signalised by the following lines:—

No sooner was success apparent than troubles commenced, as may be gathered from the following paragraph, dated September 9, 1784:—"Bath. We hear that the contractors for carrying the mail to and from this city and London have received the most positive orders to direct their coachmen: on no account whatever to try their speed against other carriages that may be set up in opposition to them, nor to suffer them to discharge firearms in passing through any towns, or on the road, except they are attacked."

"They have generally performed their duty with great care and punctuality, within an hour of the contracted time and perfectly to the satisfaction of the Government and the publick, and this before any opposition was commenced against them, and when it was thought impossible to effect it in sixteen hours instead of fifteen hours. Their steady line of conduct will be their best recommendation to this city, which, much to its honour, has supported them with great spirit. Attempts[Pg 34] by other drivers of other coaches, or any other persons whatsoever, to impede the mail diligence on its journey will be certainly attended with the most serious prosecutions to the parties so offending.

"We are desired by the old proprietors of the Bath coaches to insert the following:—

"'Last Sunday evening, as the coachman of the mail diligence was driving furiously down Kennet Hill, between Calne and Marlborough, in order to overtake the two guard coaches, the coach was suddenly thrown against the bank, by which means a lady was much hurt, as was also the driver. The lady was taken out and safely conveyed in one of the guard coaches to Marlborough.'

"We are informed:—The proprietors of the two coaches, with a guard to each, which travel from Bristol to London in fifteen hours have instructed their servants not to fire their arms wantonly, but to be particularly vigilant in case of attack. The proprietors of these coaches are determined to have the passengers and property protected and for the safety of both have ordered their[Pg 35] coachmen to keep together to make assurance doubly sure."

[By permission of S.W. Partridge & Co.,

Paternoster Row, London.

[By permission of S.W. Partridge & Co.,

Paternoster Row, London.September 16, 1784:—"Our mail diligence still continues its course with the same steadiness and punctuality. Yesterday its coachman and guard made their first appearance in Royal livery, and cut a most superior figure. It is certainly very proper that the Government carriages should be thus distinguished; such a mark of His Majesty's approbation does the contractors great honour, and it is with much pleasure we see so great a change in the conveyance of our mail—not only in its speed and safety, but in its present respectable appearance, from an old cart and a ragged boy."

December 16, 1784:—"A writer, under the signature of 'An Enemy to Schemers,' having published in the Gazette several letters against the new mode of conveying the mail, another writer, under the signature of 'Lash,' has in a masterly manner replied to all his arguments in that paper of Monday, and has severely censured the conduct of Mr. Todd of the Post Office."

December 16, 1784:—"Dear Sir,—I have just received some newspapers from a friend in Bath[Pg 36] containing an abusive letter against my post plan, and two answers to it under the signature of 'Lash.' I rather think that the latter may be yours, and think myself much obliged to you for the warmth with which you have taken the matter up, but could wish you would take no further notice of it. The letter, if I recollect right, merely contains the refuse of the observations, sent from the Post Office to the Treasury, which have been fully refuted to the board. It might appear these are like doubting the justice of that Court were I to suffer myself to be decoyed or provoked into another. Two years have already been wasted in wrangling, and I am heartily weary of it. Since my return I have the satisfaction to find the public, if possible, still more pleased from the experience they have had of the punctuality as well as the expedition of the post in all possible cases, in every variety of weather our climate gives. And those who express their surprise that the plan is not extended yet to other parts of the kingdom I have taken care to tell the plain truth—that it is entirely Mr. Todd's fault. I could not express my sense of his exceeding ill conduct at the com[Pg 37]mencement of the trial (so very different from his profession) in a stronger manner than in my memorial to the Treasury; nor could they do me ampler justice than in the resolutions they passed on the occasion and sent to the Post Office. It should not therefore be stated to the public his stopping the Norfolk and Suffolk service by his assertion of the enormous expenses of the new beyond the old system, and his strange declaration that the number of letters sent by the Bath and Bristol post had decreased and in consequence of its improvement are so ill-supported by the statements sent to the Treasury, and the reverse of these charges so fully established in my answers that I believe there is an end of the controversy, and have very little doubt but that I shall shortly receive the Ministers' commands to carry the plan into execution to the other parts of the kingdom. To do this (and I have not the least fear of accomplishing it) will be the most decisive answer to abuse, and more satisfactory to the publick. I rather think, too, from the number of memorials sent in favour of my plan, and the general indignation expressed at the mismanagement of the old[Pg 38] post, Mr. Todd will find it prudent to desist from further opposition. Nothing possible can be in better train than the plan is or in the hands of persons more anxious for its success. It would be very imprudent, therefore, to run the least hazard of disturbing it. I beg you'll not imagine I am the least displeased at what you have done. On the contrary, I am really much obliged to you; and be assured I shall never forget the zeal and attention I have experienced from you in the course of this business, and that you will always find me your sincere friend.—John Palmer, Arno's Vale, Bristol, December 2, 1784."

December 16, 1784:—"Our mail carriage has, if possible, added to its reputation from its extraordinary and ready exertions on the bad weather setting in. It arrived here on Saturday an hour only after its time, and this morning was within the limited time. The Salisbury mail, which should have come in on Saturday by eight in the morning did not arrive till Sunday morning."

January 20, 1785:—"The new regulation of our post turns out a peculiar advantage to this city, in that letters can be sent from here in the evening[Pg 39] and answered in London next morning's mails, which enables business people to stay here longer."

On February 22, 1785, the Town Council minutes contain the following:—"Mr. May acquainted the members present that the inhabitants of this city, as well as those of other places, having derived great benefit from Mr. Palmer's plan lately adopted for the improvement of the post, was the occasion of his calling them together to consider such measures as might be thought proper for continuance and extension of the said plan.... It was resolved that a memorial be sent to the Right Hon. Wm. Pitt, representing the great benefits received from the plan, and requesting a continuance of the same, together with the extension of the same plan to other parts of the kingdom."

February 17, 1785:—"At a meeting of the Bristol Merchants' Society on Saturday last, a vote of thanks was passed to Mr. John Palmer for the advantages received from his postal plan."

February 24, 1785:—"Memorials appear to the Right Hon. Wm. Pitt for the continuance and extension of Palmer's plan from the merchants,[Pg 40] tradesmen, shopkeepers in the city of Bristol, Common Council of the city of Bristol, Mayor, Burgesses and Commonality of the city of Bristol, Mayor, Aldermen and Common Councilmen of the city of Bristol."

On March 24, 1785, appeared the following letter:—"London, February 16, 1785. Sir,—Having both of us been engaged upon Committees of the House of Commons, we have been unable to present the paper you transmitted to us respecting Mr. Palmer's plan to Mr. Pitt till within these few days. Mr. Pitt has desired us to acquaint Mr. Mayor and the Corporation that he feels himself very happy to have assisted in giving such an accommodation to the city of Bath as he always hoped that plan would afford, and in which he is confirmed by the manner in which the Corporation have expressed themselves concerning it. Measures are being taken to carry it into execution through other parts of the kingdom, and the plan will be adopted in a few days upon the Norfolk and Suffolk roads.

"A. Moysey and J.J. Pratt.

"To Philip Georges, Esq., Deputy Town Clerk." [Pg 41]

May 12, 1785:—"Bath Post Office. A further extension of Mr. Palmer's plan for the more safe and expeditious conveyance of the mails took place on Monday, the 9th inst., when the letters on the cross posts from Frome, Warminster, Haytesbury, Salisbury, Romsey, Southampton, Portsmouth, Gosport, Chichester, and their delivery, together with the Isle of Wight, Jersey and Guernsey, all parts of Hampshire and Dorsetshire, will be forwarded from this office at five o'clock p.m., and every day except Sundays. Letters from the above places will arrive here every morning, Mondays excepted:

"N.B.—All letters must be put in the office before five o'clock p.m."

May 18, 1785:—"We hear that Mr. Palmer's plan for conveying the mails will be adopted from London to Manchester through Leicester and Derby, and to Leeds through Nottingham, at Midsummer."

June 9, 1785:—"Mr. Williams, the public-spirited master of the Three Tuns Inn, and the chief contractor for conveying the mails, had in the morning of this day placed in the front of his[Pg 42] house His Majesty's Arms, neatly carved in gilt. In the evening his house was illuminated in a very elegant manner with variegated lamps, the principal figure in which was the letters 'G.R.' immediately over the coat-of-arms. A band of music with horns played several tunes adapted to the day, and a recruiting party drawn up before the doors with drums and fifes playing at intervals had a very pleasing effect."

On June 30, 1785, appeared the following paragraph, which shows how complete was the success of John Palmer's post plan, in spite of all the obstacles placed in his way to obstruct his scheme. We are now informed that the "mail-coaches and diligences have been found to answer so well that they will be generally adopted throughout the kingdom, and conveying of them in carts will be discontinued."

On June 30 appeared a long letter showing how the G.P.O. tried to overthrow Mr. Palmer's scheme. This is signed Thomas Symons, Bristol, and describes the scheme as the most beneficial plan that ever was thought of for a commercial country. He also complains of the misconduct[Pg 43] of the Post Office, as letters had been miscarried to Dublin, which caused the merchants of Bristol considerable annoyance, and this mismanagement without hesitation he declares was by design, in order to try and overthrow this most excellent system of John Palmer's post.

Early in 1787, Palmer had to represent to the Contractors that the Mails must be carried by more reliable coaches.

"The Comptroller-General," he wrote to one Contractor, "has to complain not only of the horses employed on the Bristol mail, but as well of their harness and the accoutrements in use, whose defects have several times delayed the Bath and Bristol letters, and have even led to the conveyance being overset, to the imminent peril of the passengers.

"Instructions have been issued by the Comptroller for new sets of harness to be supplied to the several coaches in use on this road, for which accounts will be sent you by the harness-makers. Mr. Palmer stated also that he had under consideration, for the Contractor's use, a new-invented coach."[Pg 44]

Soon after this, Palmer's active connection with the Post Office ceased. He died at Brighton in 1818.

What he looked like at the age of 17 and 75 respectively, is shewn in the illustrations, the former taken from a picture attributed to Gainsborough.

[By permission of "Bath Chronicle."

[By permission of "Bath Chronicle."On the 25th April, 1901, the day after a visit to Bristol to celebrate the establishment of the new steamship line to Jamaica, the Marquess of Londonderry, then Postmaster-General, visited Bath to take part in a ceremony in honour of Ralph Allen and John Palmer. These two great postal reformers were both citizens of Bath, and are greatly honoured in that city for their work in the Post Office, with the famous men of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. By a happy thought there has lately been started a movement to keep alive associations with the past by placing tablets on the houses in which famous men lived. One of the tablets unveiled by Lord Londonderry was placed on the house in which Ralph Allen first conducted the business of the Bath Post Office,[Pg 46] and of his cross post contracts, and the other on the house in which John Palmer was born.

Soon after noon on the eventful day, the Bath postmen's band, Mr. Kerans, the postmaster, and his lieutenants, the staff of postmen and messengers, marched on to the space between the Abbey and the Guildhall for inspection by the Head of the Post Office Department. After the inspection, a procession was formed, in which the Postmaster-General was accompanied by the Mayor, and followed by the Town Councillors, two by two. Before them went the city swordbearer, clad in striking robes, and the party proceeded to the North Parade, from which Allen's house is now reached by a passage way. The house is built of stone, and has a very handsome front in the style of the classical Renaissance. In drawing aside the curtain, which veiled the tablet, on which was inscribed "Here lived Ralph Allen, 1727-1764," Lord Londonderry said that there was probably not one of the great men who had been associated with Bath who was more of a benefactor to his town, as well as to the public service of his country, than Ralph Allen. The[Pg 47] procession then moved on to Palmer's house, only a few yards away, where a similar ceremony took place. After another short speech by the Postmaster-General, in which he explained the share Palmer had borne in developing the modern Post Office system, the second tablet was unveiled. It bore the inscription, "Here lived John Palmer, born 1741, died 1818."

Afterwards at the Guildhall, where a bust of Allen in the Council Chamber looked down upon a large party assembled for luncheon, the Postmaster-General, in response to the toast of his health, discoursed more at large upon the topic of the day. He congratulated Bath upon having among its citizens two out of the four great men of Post Office history. It was Allen's task to provide a general postal system by opening up new lines of posts between the main roads, and through new lines of country. Between 1720, when he began his first contract, and 1764 when he died, he covered the country with a network of posts, giving easy communication between all important towns, and he also increased the number and speed of the mails on the post roads. While[Pg 48] doing this he raised himself from being a humble clerk, and later, postmaster of Bath, to a position of great affluence, and of friendship with many of the great men of his time. Among those friends was Lord Chatham.

It was twenty years after Allen's death that Palmer's Mail Coach system was started. Its advantage soon made itself apparent, and the improvement of roads at the end of the 18th Century enabled the mail coach service to be brought to great perfection. It lasted less than 60 years, but in those years correspondence and the revenue of the Post Office multiplied many times, and when Rowland Hill turned his attention to postal questions he found a rapid and efficient service, which was at the same time so cheap that the cost of conveyance was only a small item in the expenses of the Post Office.

The Mayor of Bath proposed the toast of "the Visitors," and said that they had amongst them two representatives of the great men they were honouring. Ralph Allen was represented by Colonel Allen, a direct descendant, and the owner of Bathampton Manor, a part of Ralph Allen's[Pg 49] estate. Colonel Allen had lately returned from South Africa. John Palmer was represented by his grandson, Colonel Palmer, R.E.

[From a block kindly lent by the

Proprietors of the "Bath Chronicle."]

MEDAL STRUCK IN HONOUR OF RALPH ALLEN.

Colonel Allen thanked the company for their kind reception, and Colonel Palmer said that it had given him the greatest pleasure to witness the testimonial to his grandfather's services, and this pleasure would be shared by the members of his family, including his sister, who had given the cup on the table to the Corporation. It had been a present from the Citizens of Glasgow to John Palmer.

Full accounts of the Post Office services of Allen and Palmer are written in "The Bristol Royal Mail."

The photograph of a curious memorial of Ralph Allen's work in the Post Office here reproduced is that of a medal bearing the Royal Arms, and the inscriptions "To the Famous Mr. Allen, 4th December, 1752," and "the Gift of His Royal Highness, W.D. of Cumberland."

The reverse of the medal is engraved with some Masonic emblems, and with the words,[Pg 50]

"Amor Honor Justitia,"

Ino Campbell,

Armagh.

No. 409.

The history of this relic is rather obscure. It was purchased in a curiosity shop in Belfast some fifteen years ago by Mr. D. Buick, LL.D., of Sandy Bay, Larne. In the year 1752, the Princess Amelia visited Bath, and was entertained by Ralph Allen at Prior Park. During her stay at Bath, the Duke of Cumberland also visited the town, and is known to have contributed £100 to the Bath Hospital, of which Allen was one of the most active supporters. It has been surmised that the medal was intended as an acknowledgment of the courtesy and attention received by the Duke and the Princess on this occasion.

Whether the medal was ever presented is not known, or how it came to be converted into a Masonic jewel. Perhaps it may have been given away by Allen, or it may have gone astray, or been stolen. The Masonic Lodge, No. 409, is said to have been founded by a Mr. John Campbell in 1761, shortly before the date of Allen's death: Allen may have been a Freemason.

[By permission of Mr. Sydenham, of Bath.

[By permission of Mr. Sydenham, of Bath.It is to Mr. Sydenham, of Bath, that indebtedness is due for the interesting impressions of tokens struck in commemoration of Palmer's mail coach system here depicted.

An interesting tribute was the painting by George Robertson, engraved by James Fittler, and inscribed to him as Comptroller-General in 1803, eleven years after he had ceased to hold that position. A copy of this engraving appears in "The Bristol Royal Mail." Palmer also received the freedom of eighteen towns and cities in recognition of his public services, was Mayor of Bath in 1796 and 1801, and represented that city in the four Parliaments of 1801, 1802, 1806, and 1807.

Francis Freeling, who succeeded John Palmer in the Secretaryship and General Managership of Post Office affairs, was as a youth a disciple of his predecessor, and assisted him in the development of the Mail Coach system. He was apprenticed to the Post Office in Bristol, where his talents, rectitude of conduct, and assiduity in the duties assigned him gained for him the esteem and respect of all those connected with the estab[Pg 52]lishment; and, on the introduction by Mr. Palmer of the new system of Mail Coaches, Mr. Freeling was appointed in 1785 his assistant to carry the improvements into effect. He was introduced into the General Post Office in 1787, and successively filled the office of surveyor, principal surveyor, joint secretary with the late Anthony Todd, Esq., and sole secretary for nearly half a century.

In Mr. Dix's "Life of Chatterton," it is stated, on the authority of a friend of the Chatterton family, that on Chatterton leaving for London, "he took leave of several friends on the steps of Redcliff Church very cheerfully. That at parting from them he went over the way to Mr. Freeling's house." It is further stated that Mr. Freeling was father to the late Sir F. Freeling.

As regards Freeling's birthplace, information is forthcoming which seems conclusive. In a collection of old Bristol sketches purchased for the Museum and Library, there is a beautiful drawing of Redcliffe Hill, executed about eighty years ago; and the artist, doubtless acting on[Pg 53] the evidence of old inhabitants—contemporaries of Freeling—has distinctly marked the house where that gentleman was born, and noted the fact in his own handwriting.

+ BIRTHPLACE OF SIR FRANCIS FREELING, BART.,

+ BIRTHPLACE OF SIR FRANCIS FREELING, BART.,Permission has been obtained from the council of the Bristol Museum and Reference Library for the picture to be photographed. The following is the superscription on the back of the original pencil drawing:—"Redcliffe Pit, Bristol. The house with this mark + at the door is the house in which Sir Francis Freeling, Bart., was born. The high building, George's patent shot tower, G. Delamotte, del. Jan. 12, 1831." A copy of the sketch is here reproduced. The house as "set back" or re-erected is now known as 24, Redcliffe Hill.

Sir Francis Freeling first carried on his secretarial duties at the old Post Office in Lombard Street, once a citizen's Mansion. There he was located for 30 years.

On September 29th, 1829, the Lombard Street Office was abandoned as Headquarters, and Freeling moved, with the secretarial staff under his chieftainship, to St. Martin's-le-Grand.[Pg 54]

In 1833 the question arose whether the mail coaches should be obtained by public competition, or by private agreement, but Sir Francis Freeling's idea was to get the public service done well, irrespective of the means.

On this point Mr. Joyce, C.B., in his history of the Post Office, wrote that in 1835 the contract for the supply of mail coaches was in the hands of Mr. Vidler, of Millbank, who had held it for more than 40 years, and little had been done during this period to improve the construction of the vehicles he supplied. Designed after the pattern in vogue at the end of the last century, they were, as compared with the stage coaches, not only heavy and unsightly, but inferior both in point of speed and accommodation. Commissioners appointed to inquire into the system, altogether dissatisfied with the manner in which the contract had been performed, arranged with the Government not only that the service should be put up to public tender, but that Vidler should be excluded from the competition. This decision was arrived at in July, 1835, and the contract expired on the 5th of January following. To[Pg 55] invite tenders would occupy time, and after that mail coaches would have to be built sufficient in number to supply the whole of England and Scotland. A period of five or six months was obviously not enough for the purpose, and overtures were made to Vidler to continue his contract for half a year longer. Vidler, incensed at the treatment he had received, flatly refused. Not a day, not an hour, beyond the stipulated time would he extend his contract, and on the 5th of January, 1836, all the mail coaches in Great Britain would be withdrawn from the roads. Freeling, now an old man, with this difficulty to overcome, had his old energy revived, and when the 5th of January arrived there was not a road in the kingdom, from Wick to Penzance, on which a new coach was not running. It was then that the mail coaches reached their prime.

Amongst the deaths announced in the Felix Farley's Journal under date of January 14th, 1804, is that of "the lady of Francis Freeling, Esq., of the General Post Office," and another part of the paper contains the following paragraph:[Pg 56]—

"The untimely death of Mrs. Freeling is lamented far beyond the circle of her own family, extensive as it is. The amiableness of her manner and the rational accomplishments of her mind had conciliated a general esteem for such worth, through numerous classes of respectable friends, who naturally participate in its loss."

Freeling's obituary notice, which appeared in the same Journal on July 16, 1836, ran as follows:

"Saturday last, died at his residence in Bryanston Square, London, in the 73rd year of his age, Sir Francis Freeling, Bart., upwards of 30 years Secretary to the General Post Office. Sir Francis was a native of Bristol—he was born in Redcliffe Parish—and first became initiated in the laborious and multifarious duties attendant upon the important branch of the public service in which he was engaged in the Post Office of this city of Bristol, from whence he was removed to the Metropolitan Office in Lombard Street, on the recommendation of Mr. Palmer, the former M.P. and Father of George Palmer, the present member for Bath, who had observed during the period he was employed in first establishing the mail-[Pg 57]coach department the quickness of apprehension, the aptitude for business, and the steadiness of conduct of his youthful protégé. Sir Francis rapidly rose to notice and preferment in his new situation; and after his succession to the office of Chief Secretary, it is proverbial that no public servant ever gave more general satisfaction by his indefatigable attention to the interests of the community, or than he invariably shewed to those of the meanest individual who addressed him; whether from a peer or peasant, a letter of complaint always received a prompt reply. The present admirable arrangements and conveniences of that noble national establishment, the newly-erected Post Office, were formed upon the experience and the suggestions of Sir Francis and his eldest son. A more faithful and zealous servant the public never possessed. The title he enjoyed was the unsolicited reward for his services, bestowed upon him by his Royal Master George the 4th, from whom he frequently received other flattering testimonials of regard and friendship. In Sir Francis Freeling was to be found one of those instances which so frequently[Pg 58] occur in this country of the sure reward to industry and talent when brought into public notice. In speaking of his private character, those only can appreciate his worth who saw him in the bosom of his family—to his fond and affectionate children his loss will be irreparable. To possess his friendship was to have gained his heart, for it may be truly said he never forgot the friend who had won his confidence; particularly if the individual was one who, like himself, had wanted the fostering hand of a superior. Sir Francis was always found to be the ready and liberal patron of talent in every department of literature, science, and the fine arts. Considering the importance and multiplicity of his public avocations, it was surprising to all his friends how he could have found leisure to store his mind with the knowledge he had attained of the works and beauties of all our most esteemed writers; his library contains one of the rarest and most curious collections of our early authors, more particularly our poets and dramatists; in the acquirement of these works he was engaged long before it became the fashion to purchase a[Pg 59] black letter poem, or romance, merely because it was old or unique. But his highest excellencies were the virtuous and religious principles which governed his whole life; his purse was ever open to relieve the distress of an unfortunate friend, or the wants of the deserving poor. Many were the alms which he bestowed in secret; which can be testified by the writer of this paragraph, who knew him well, and enjoyed his friendship."

Miss Edith Freeling, now resident in Clifton, grand-daughter of Sir Francis Freeling, and daughter of Sir Henry Freeling, and who was actually born in the General Post Office, St. Martin's-le-Grand, London, where her father had a residence as Assistant Secretary, has in her possession several "antiques" belonging to her ancestors.

A worn-out despatch box used by Sir Francis in sending his papers to the Postmaster-General is one of the prized articles. A very handsome gold seal cut with the Royal Arms, and bearing the legend—General Post Office Secretary—is another of the relics. Likewise a smaller gold[Pg 60] seal with a Crown, and "God Save the King," as its legend.

At the time of his death, Sir Francis Freeling's snuff boxes numbered 72, the majority of which had been presented to him. Apparently "appreciations" took a tangible form in those days! His son, Sir Henry, likewise had snuff boxes presented to him.

A handsome specimen snuff box is now in Miss Freeling's hands. It is made of tortoise-shell, it has the portrait of King George the IVth as a gold medallion on the top, and was known as a Regency Box. The inscription inside is, "This box was presented to G.H. Freeling by His Majesty George IVth on board the Lightning steam packet on his birthday twelfth August 1821 as a remembrance that we had been carried to Ireland in a Steam Boat." As Sir Francis Freeling migrated from the Bristol service to Bath in 1784, it must have been at the Old Bristol Post Office, near the Exchange, indicated by the illustration, that he commenced that public career which was destined to be one of brilliant achievements for the department during the many years he presided over[Pg 61] it as permanent chief, and of great good to his country in the way of providing means for people to communicate with each other more readily than was the case before his day.

THE OLD BRISTOL POST OFFICE IN EXCHANGE AVENUE.

THE OLD BRISTOL POST OFFICE IN EXCHANGE AVENUE.

How our forefathers got about the country, and how the Mails were carried as time went on after Allen and Palmer had disappeared from Mail scenes, and Freeling had taken up the reins, the following announcements, taken from Bonner and Middleton's Bristol Journal, and from the Bristol Mirror respecting Mail Stage Coaches will aptly indicate. They are quoted just as they appeared, so that editing may not spoil their originality or interest:—

"A letter from Exeter, dated May 10, 1802, said:—'Last Thursday the London mail, horsed by Mr. J. Land, of the New London Inn, Exeter, with four beautiful grey horses, and driven by Mr. Cave-Browne, of the Inniskilling Dragoons, started (at the sound of the bugle) from St. Sydwells, for a bet of 500 guineas, against the[Pg 63] Plymouth mail, horsed by Mr. Phillips, of the Hotel, with four capital blacks, and driven by Mr. Chichester, of Arlington House, which got the mail first to the Post Office in Honiton. The bet was won easily by Mr. Browne, who drove the sixteen miles in one hour and fourteen minutes.—Bets at starting, 6 to 4 on Mr. Browne. A very great concourse of people were assembled on this occasion.'"

On Saturday, October 2, 1802, it was announced that "the Union post coach ran from Bristol every Sunday, Wednesday and Friday morning over the Old Passage, through Chepstow and Monmouth to Hereford, where it met other coaches, and returned the following days. Coaches left the White Hart Inn and the Bush Tavern for Exeter and Plymouth every morning, by the nearest road by ten miles. Fares: To Exeter, inside, £1 1s.; outside, 14s.; to Plymouth, £1 11s. 6d. and £1 1s. Reduced fares are offered by the London, Bath, and Bristol mail coaches—to and from London to Bristol, inside, £2 5s.; from London to Bath, £2. Parcels under 6lb. in weight taken at 6d. each, with an engagement[Pg 64] to be responsible for the safe delivery of such as are under £5 in value."

In August, 1803, passenger traffic to Birmingham caused rivalry among the coach proprietors. A new coach having started on this route, three coaching advertisements were issued:—

Under the heading "Cheap Travelling to Birmingham," the "Jupiter" coach was announced to run from the White Lion, Broad Street, every Monday and Friday afternoon, at two o'clock; through Newport, Gloucester, Tewkesbury, and Worcester to Birmingham; the "Nelson" coach from the Bush Tavern and White Hart every morning at three; and the mail every evening at seven. "Performed by Weeks, Williams, Poston, Coupland and Co."

The "Union" coach altered its times of leaving the Boar's Head, College Place—"in order to render the conveyance as commodious and expeditious as possible"—to Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday mornings at seven o'clock, over the Old Passage, through Chepstow, Monmouth, Abergavenny, and Hereford, where it met the Ludlow, Shrewsbury, Chester, and Holyhead[Pg 65] coaches, and returned the following days, and met the Bath, Warminster, Salisbury, and Southampton coaches every Saturday, Tuesday, and Thursday mornings at seven o'clock. "Performed by W. Williams, Bennett, Whitney, Broome, Young and Co."

"A new and elegant coach, called the 'Cornwallis,'" left the Lamb Inn, Broadmead, every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday afternoon, at two o'clock, through Newport, Gloucester, Tewkesbury and Worcester, to the George and Rose Inn, Birmingham, where it arrived early the next morning, whence coaches set off for the Midlands, North Wales, and the North of England. The proprietors pledged themselves that no pains should be spared to make this a favourite coach with the public; and as one of the proprietors would drive it a great part of the way, every attention would be paid to the comfort of passengers. The fares of this coach would at all times be as cheap as any other coach on the road, and the proprietors expected a preference no longer than whilst endeavouring by attention to merit it. "Performed by Thomas Brooks and Co., Bristol."[Pg 66]

March 10, 1804:—"The 'Cornwallis' coach to Birmingham is to set out from the Swan Inn, Maryport Street, at three every morning, Sundays excepted, through Newport, Gloucester and Worcester, and arrive at the Rose Inn, Birmingham, early the same evening. The fares of this coach and the carriage of goods will be found at all times as cheap as any other coach on the road." At this period Admiral Cornwallis, whose name this coach bore, was fighting the French with his fleet off Brest.

On August 19, in that year (1804), the public were respectfully informed, that "a light four-inside coach leaves the original Southampton and general coach offices, Bush Inn and Tavern, Bristol, every morning (Sundays excepted), at seven o'clock precisely, and arrives at the Coach and Horses Inn, Southampton, at five in the afternoon. The Gosport coach, through Warminster, Salisbury, Romsey and Southampton, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday mornings at five o'clock. To Brighton, a four-inside coach in two days, through Warminster, Salisbury, Romsey, Southampton, Chichester, Arundel, Worthing[Pg 67] and Shoreham, on Monday, Wednesday and Friday mornings at seven, sleeps at Southampton, and arrives early the following afternoon. Portsmouth Royal Mail, through Warminster, Sarum, Romsey, and Southampton every afternoon at three o'clock. Also the Oxford Royal Mail, every morning at seven o'clock."

On August 18, 1823, the state of the roads comes under review:—"Mail men, who have to drive rapidly over long distances, must ever be on the look-out for the state in which the roads are kept.

"In December, 1819, Mr. Johnson, Superintendent of Mail Coaches, had to report to the House of Commons on the 'petition of Mr. McAdam,' who was engaged in constructing and repairing of the public roads.

"Previous to this the roads were very bad in most country places, except the mail coach roads, built at the time the Romans came to England.

"McAdam's expenses up to 1814 amounted to £5,019 6s., actually expended by him up to August, 1814, and he had travelled 30,000 miles in 1,920 days.[Pg 68]

"He held the position of general surveyor of the Bristol turnpike roads, at a salary, first year £400, and each subsequent year of £500, but, taking into account that the annual salary was £200 for expenses 'incident' to the office, the remaining £300 was not more than adequate payment for the constant and laborious duties attached to the situation."