Chapter XV

THE CULTURE OF THE

CIVILIZED TRIBES.1

Different views on this question—Reason

for the same—Their architecture—Different styles of

houses—The communal house—The tecpan—The

teocalli—State of society indicated by this

architecture—The gens among the Mexicans—The phratry

among the Mexicans—The tribe—The powers and duties of

the council—The head chiefs of the tribe—The duties

of the "Chief-of-men"—The mistake of the

Spaniards—The Confederacy—The idea of property among

the Mexicans—The ownership of land—Their

laws—Enforcement of the laws—Outline of the growth of

the Mexicans in power—Their tribute system—How

collected—Their system of trade—Slight knowledge of

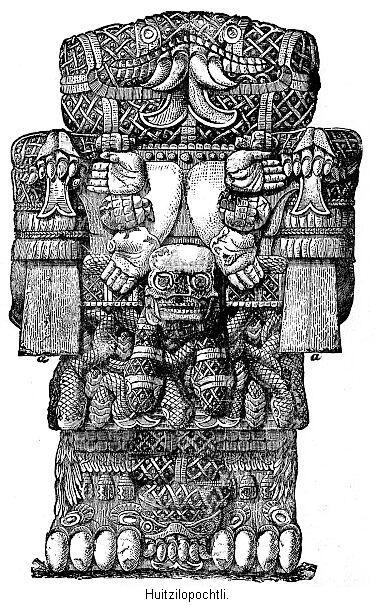

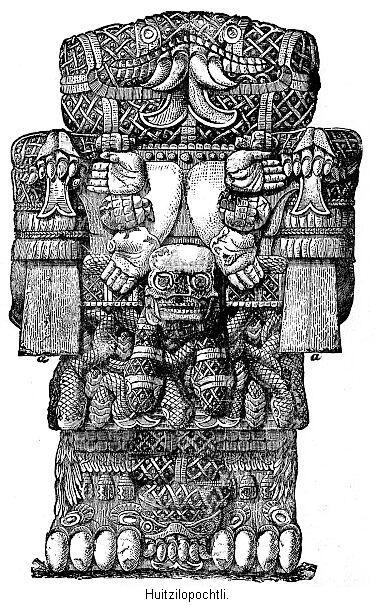

metallurgy—Religion—Quietzalcohuatl—Huitzilopochtli—Mexican

priesthood—Human sacrifices—The system of

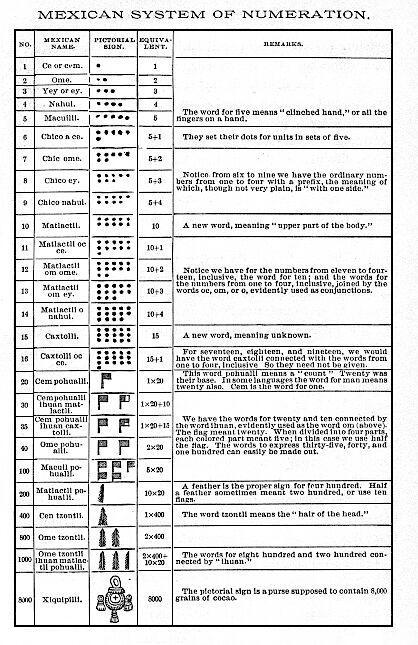

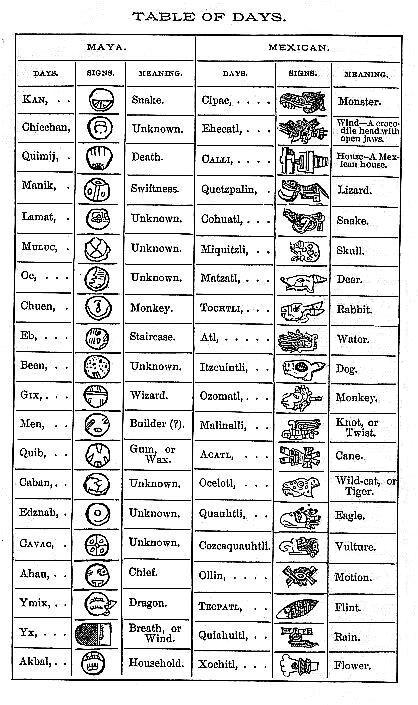

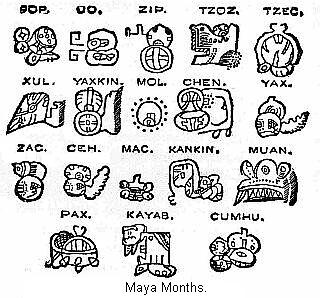

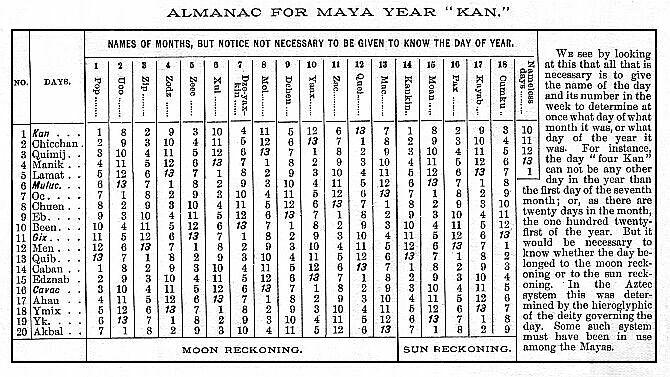

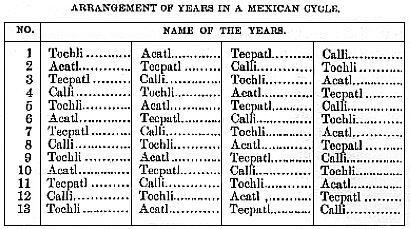

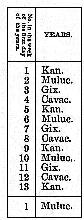

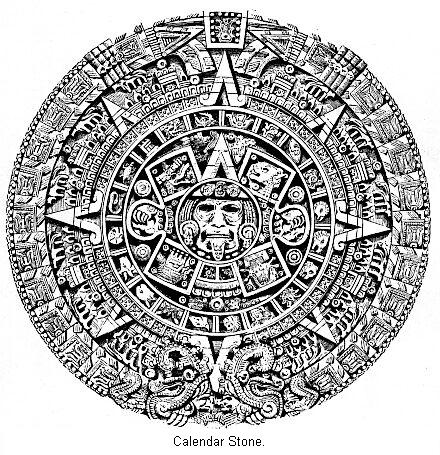

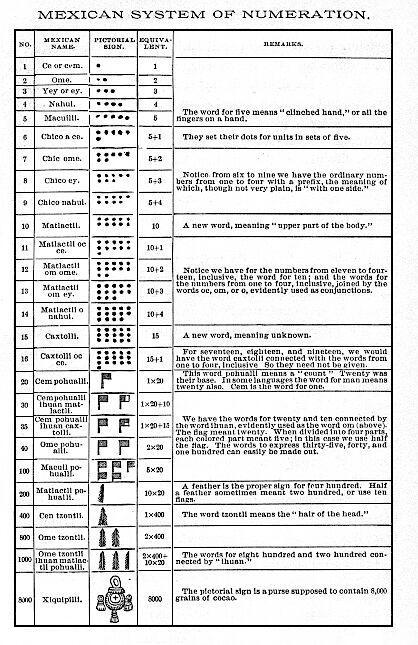

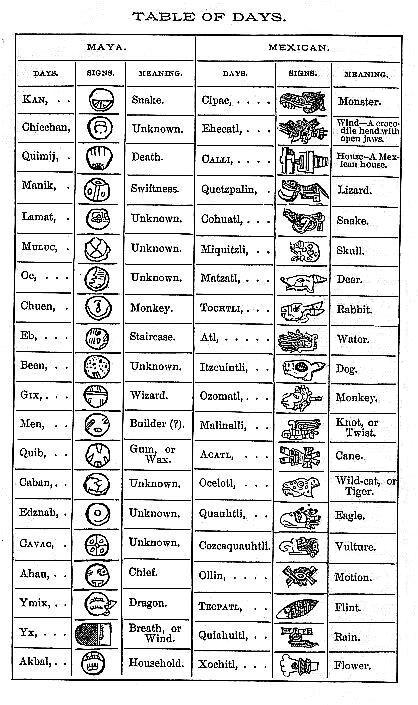

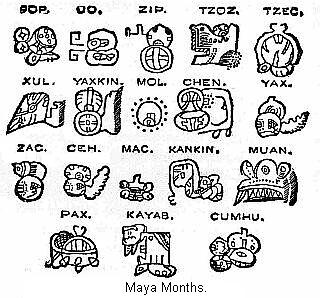

Numeration—The calendar system—The calendar

stone—Picture writing—Landa alphabet—Historical

outline.

LANDSCAPE presents varied aspects

according to the standpoint from which it is viewed. Here we have

a glimpse of hill and dale; there a stretch of running water. But

two persons, standing in the same position, owing to their

different mental temperaments, will view things in a different

light. Where one, an artist born, is carried away with the

beautiful scenery, another, with a more practical turn of mind,

perceives only its adaptability for investments. Education and

habits of life are also very potent factors in determining our

views on various questions. Scholars of wide and extended

learning differ very greatly in their views of questions deeply

affecting human interests. We know how true that is of abstruse

topics, such as religion and questions of state polity. It is

also true of the entire field of scientific research. The unknown

is a vastly greater domain than the known, and men, after deep

and patient research, adopt widely different theories to explain

the same facts.

LANDSCAPE presents varied aspects

according to the standpoint from which it is viewed. Here we have

a glimpse of hill and dale; there a stretch of running water. But

two persons, standing in the same position, owing to their

different mental temperaments, will view things in a different

light. Where one, an artist born, is carried away with the

beautiful scenery, another, with a more practical turn of mind,

perceives only its adaptability for investments. Education and

habits of life are also very potent factors in determining our

views on various questions. Scholars of wide and extended

learning differ very greatly in their views of questions deeply

affecting human interests. We know how true that is of abstruse

topics, such as religion and questions of state polity. It is

also true of the entire field of scientific research. The unknown

is a vastly greater domain than the known, and men, after deep

and patient research, adopt widely different theories to explain

the same facts.

It need, therefore, occasion no surprise to

learn that there is a great difference of opinion as to the real

state of culture among the so-called civilized tribes of Mexico

and Central America. We have incidentally mentioned this

difference in describing the ruins and their probable purpose. As

one of the objects we have in view, and perhaps the most

important one, is to learn what we can of the real state of

society amongst the prehistoric people we treat of, it becomes

necessary to examine these different views, and, if we can not

decide in our own minds what to accept as true, we will be

prepared to receive additional evidence that scholars are now

bringing forward, and know to how weigh them and compare them

with others.

It has only been within the last few years

that we have gained an insight into the peculiar organization of

Indian society. After some centuries of contact between the

various tribes of Indians and whites, their social organization

was still unknown. But we are now beginning to understand this,

and the important discovery has also been made that this same

system of government was very widely spread, indeed. This subject

has, however, been as extensively treated as is necessary in

chapter xii, so we need not stop longer. But if, with all the

light of modern learning, we have only lately gained a clear

understanding of the social organization of Indian tribes, it

need occasion no surprise, nor call for any indignant denial, to

affirm that the Spaniards totally misunderstood the social

organization of the tribes with which they came in contact in

Mexico.

We must also take into consideration the

political condition of Europe at this time. Feudalism still

exercised an influence on men's minds. The Spanish writers, in

order to convey to Europeans a knowledge of the country and its

inhabitants, applied European names and phrases to American

Indian (advanced though they were) personages and institutions.

But the means employed totally defeated the object sought.

Instead of imparting a clear idea, a very erroneous one was

conveyed.

As an illustration of this abuse of language,

we might refer to the case of Montezuma, which name itself is a

corruption of the Mexican word "Motecu-zoma," meaning literally

"my wrathy chief." Mr. Bandelier2

and Mr. Morgan have quite clearly shown what his real position

was. His title was "chief of men."3 He was simply one of the two chief

executive officers of the tribe and general of the forces of the

confederacy. His office was strictly elective, and he could be

deposed for misdemeanor. Instead of giving him his proper title,

and explaining its meaning, the Spaniards bestowed on him the

title of king, which was soon enlarged to that of emperor,

European words, it will be observed, which convey an altogether

wrong idea of Mexican society. Many such illustrations could be

given.

The literature that has grown up about this

subject is very voluminous, but the authors not being acquainted

with the organization of Indian society, have not been able to

write understandingly about them. We do not flatter ourselves

that we have now solved all the difficulties of the case. But

since Mr. Morgan has succeeded in throwing such a flood of light

on the constitution of ancient society, and especially of Indian

society, and Mr. Bandelier has given us the results of his

careful investigation of the culture of the Mexicans, we feel

that a foundation has been laid for a correct understanding of

this vexed problem.

We will now examine their architecture, or

style of building. In dealing with prehistoric people, we have

several times referred to the tribal state of government,

involving village life and communism in living. We have seen how

this principle enabled us to understand the condition of Europe

during the Neolithic Age. In still another place we have used

this principle to show the connection of the Pueblo Indians and

other tribes of the United States. Now we think this is the key

which is to explain many of the ruins we have described in the

preceding chapter. But another principle to be borne in mind, is

that of defense. War, we have seen, is really the normal state of

things amongst tribal communities. Therefore, either some

position naturally strong must be selected as a village site, or

the houses themselves must be fortified, after the fashion of

Indians. This will be found to explain many peculiarities in

their method of construction.

Amongst the pueblo structures of to-day, and

among the ruins of the cliff-dwellers, we have seen how compact

every thing was. The estufa, or place of council and worship, was

built in close proximity to the other building, and sometimes it

formed part of it, and we do not learn that there was any thing

distinguishing about the apartments of the chief. Further South a

change is noticed. A specialization of structures, if we may use

such an expression, has taken place, and, among the Mexicans,

three kinds of houses were distinguished. It is extremely

probable the same classification could be made elsewhere. There

was, first of all, the ordinary dwelling houses. Every vestige of

aboriginal buildings in the pueblos of Mexico has long since

disappeared, and our knowledge of these structures can only be

gathered from the somewhat confused accounts of the early

writers.

Many, perhaps most, of the houses had a

terraced, pyramidal foundation. Some were constructed on three

sides of a court, like those on the Rio Chaco, in New Mexico.

Others probably surrounded an open court, or quadrangle. The

houses were of one and two stories in height. When two stories,

the upper one receded from the first, probably in the terraced

form. As serving to connect them with the more ornamental

structures in Yucatan, we are told they were sometimes "adorned

with elegant cornices and stucco designs of flowers and animals,

which were often painted with brilliant colors. Prominent among

these figures was the coiling serpent."4 After pointing out, by many citations,

that the evidence always was that these houses were occupied by

many families, Mr. Morgan concludes, "They were evidently joint

tenement-houses of the aboriginal American model, each occupied

by a number of families ranging from five and ten to one hundred,

and perhaps, in some cases, two hundred families in a house."5

We can discern this kind of dwelling-house in

many of the descriptions we have given of the ruins in the

preceding chapter. M. Charney evidently found them at Tulla and

Teotihuacan. Mr. Bandelier concludes that similar ruins once

crowded the terraces at Cholula, and that to this class belongs

the ruins at Mitla. The Palace, at Palenque, is evidently but

another instance, as well as the House of Nuns, at Uxmal. In

fact, with our present knowledge of the pueblos of Arizona, and

the purposes which they subserved, as well as the uses made of

such houses by the Mexicans, we are no longer justified in

bestowing upon the structures in Yucatan the name of palaces.

The mistake was excusable among the Spaniards.

They were totally ignorant of the mode of life indicated by these

joint tenement-houses. When they found one of these large

structures, capable of accommodating several hundred occupants,

with its inner court, terraced foundation, and ornamented by

stucco work, or sculpture, it was extremely natural that they

should call it a palace, and cast about for some titled

owner.

A second class of houses includes public

buildings. The Mexicans, when at the height of their power,

required buildings for public use, and this was doubtless true of

the people who inhabited Uxmal and Palenque. The most important

house was the tecpan, the official house of the tribe, the

council house proper. This was the official residence of the

"chief of men" and his assistants, such as runners. This was the

place of meeting of the council of chiefs. It was here that the

hospitality of the Pueblo was exercised. Official visitors from

other tribes and traders from a distance were provided with

accommodations here. When Cortez and his followers entered Mexico

they were provided for at the tecpan. We would not expect to find

these public buildings, except in rich and prosperous pueblos. It

has been suggested that the Governor's House at Uxmal was the

official house of that settlement. The large halls, suitable for

council purposes, favor this idea.6

A third class of buildings was the teocalli,

or "House of God"—in other words, the temple. These were

quite common. Each of the gens that composed the Mexican tribe

had its own particular medicine lodge or temple. This was

doubtless true of each and every tribe of sedentary Indians in

the territory we are describing. "The larger temples were usually

built upon pyramidal parallelograms, square or oblong, and

consisted of a series of superimposed terraces with perpendicular

or sloping sides."7 It is not

necessary to dwell longer on this style of buildings. We have

only to recall the temples of the Sun, of the Cross, and of the

Beau-relief at Palenque; the House of the Dwarf at Uxmal, and the

Citadel at Chichen-Itza, to gather a clear idea of their

construction.

The architecture of a people is a very good

exponent of their culture. Yet all have seen what different views

are held as to the culture of the tribes we are considering. We

have, perhaps, said all that is required on this part of the

subject, yet even repetition is pardonable if it enables us to

more clearly understand our subject. The ornamentation on the

ruins of Yucatan is so peculiar that in our opinion it has unduly

influenced the judgment of explorers in this matter. They lose

sight of the fact that the apartments of the houses are small,

dark, and illy ventilated.

That they should hive gone to the trouble of

so profusely decorating their usual places of abode is, indeed,

somewhat singular.8 But Mitla was

certainly an inhabited pueblo at the time of the Spanish

conquest, and there is no good reason for concluding it was ever

any thing more than a group of communal buildings. Yet, from the

description given of it, we can not see that the buildings are

greatly inferior in decoration to the structures in Yucatan. And

yet again, from the imperfect accounts we have of the aboriginal

structures in the pueblo of Mexico, we infer they were

constructed on the general plan of communal buildings. As for the

decorations, we have seen they had sometimes elaborate cornices,

and were covered with stucco designs of animals and flowers. In

this case some of them were, to be sure, public buildings for

tribal purposes, but the majority of them were certainly communal

residences. With these facts before us, we can not do otherwise

than conclude that these so-called ruins of great cities we have

described are simply the ruins of pueblos, consisting of communal

houses, temples, and, in the case of large and powerful tribes,

official houses. To this conclusion we believe American scholars

are tending more and more.

This requires us to dismiss the idea that the

majority of the people lived in houses of a poorer construction,

which have since disappeared, leaving the ruins of the houses of

the nobles. There was no such class division of the people as

this would signify. These ruins were houses occupied by the

people in common. With this understanding, a questioning of the

ruins can not fail to give us some useful hints. We are struck

with their ingenuity as builders. They made use of the best

material at hand. In Arizona the dry climate permits of the use

of adobe bricks, which were employed, though stone was also used.

Further south the pouring tropical rains would soon bring down in

ruins adobe structures and so stone alone is used.

In the Arizona pueblo we have a great

fortress-built house, three and four stories high, and no mode of

access to the lower story. This is in strict accord with Indian

principles of defense, which consists in elevated positions.

Sometimes this elevated position was a natural hill, as at

Quemada, Tezcocingo, and Xochicalco. Where no hill was at hand

they formed a terraced pyramidal foundation, as at Copan,

Palenque, and Uxmal. In the highest forms of this architecture

this elevation is faced with stone, or even composed throughout

of stone, as in the case of the House of Nuns at Chichen-Itza. In

the construction of houses progress seems to have taken place in

two directions. The rooms increased in size. In some of the

oldest pueblo structures in Arizona the rooms were more like a

cluster of cells than any thing else.9

They grow larger towards the South. In the

house at Teotihuacan M. Charney found a room twenty-seven feet

wide by forty-one feet long. Two of the rooms in the Governor's

House at Uxmal are sixty feet long. But the buildings themselves

diminish in size. In Mexico the majority of the houses were but

one story high, and but very few more than two stories. In

Yucatan but few instances are recorded of houses two stories

high. We must remember that throughout the entire territory we

are considering the tribes had no domestic animals, their

agriculture was in a rude state, and they were practically

destitute of metals.10 They could

have been no farther advanced on the road to civilization than

were the various tribes of Europe during the Bronze Age.

Remembering this, we can not fail to be impressed with the

ingenuity, patient toil, and artistic taste they displayed in the

construction and decoration of their edifices.

It may seem somewhat singular that we should

treat of their architecture before we do of their system of

government, but we were already acquainted with the ruins of the

former. When we turn to the latter we find ourselves involved in

very great difficulties. The description given of Mexican society

by the majority of writers on these topics represent it as that

of a powerful monarchy. The historian Prescott, in his charming

work11 draws a picture that would

not suffer by comparison with the despotic magnificence of

Oriental lands. At a later date Mr. Bancroft, supporting himself

by an appeal to a formidable list of authorities, regilds the

scene.12 But protests against

such views are not wanting. Robertson, in his history, though

bowing to the weight of authority can not forbear expressing his

conviction that there had been some exaggeration in the splendid

description of their government and manners.13 Wilson, more skeptical, and bolder,

utterly repudiates the old accounts, and refuses to believe the

Aztecs were any thing more than savages.14

With such divergent and conflicting views, we

at once perceive the necessity of carefully scanning all the

accounts given, and make them conform, if possible, to what is

known of Indian institutions and manners. The Mexicans are but

one of several tribes that are the subjects of our research; but

their institutions are better known than the others, and, in a

general way, whatever is true of them will be true of the rest.

We have seen the efforts of the Spanish explorers to explain

whatever they found new or strange in America by Spanish words,

and the results of such procedure. We are at full liberty to

reject their conclusions and start anew.

What the Spaniards found around the lakes of

Mexico was a union or confederacy of three tribes. Very late

investigations by Mr. Bandelier have established the presence of

the usual subdivisions of the tribes. So we have here a complete

organization according to the terms of ancient society: that is,

the gens, phratry, tribe, and confederacy of tribes. It is

necessary that we spend some time with each of these subdivisions

before we can understand the condition of society among the

Mexicans, and, in all probability, the society among all of the

civilized nations of Central America.

We will begin with the gens, or the lowest

division of the tribe. We must understand its organization before

we can understand that of a tribe, and we must master the tribal

organization before attempting to learn the workings of the

confederacy. To neglect this order, and commence at the top of

the series, is to make the same mistake that the older writers

did in their studies into this culture. A gens has certain

rights, duties, and privileges which belong to the whole gens,

and we will consider some of the more important in their proper

place. We must understand by a gens a collection of persons who

are considered to be all related to each other. An Indian could

not, of his own will, transfer himself from one gens to another.

He remained a member of the gens into which he was born. He

might, by a formal act of adoption, become a member of another

gens; or he might, in certain contingencies, lose his connection

with a gens and become an outcast. There is no such thing as

privileged classes in a gens. All its members stand on an equal

footing. The council of the gens is the supreme ruling power in

the gens. Among some of the northern tribes, all the members in

the gens, both male and female, had a voice in this council. In

the Mexican gens, the council itself was more restricted. The old

men, medicine men, and distinguished men met in council—but

even here, on important occasions, the whole gens met in

council.

Each gens would, of course, elect its own

officers. They could remove them from office as well, whenever

occasion required. The Mexican gentes elected two officers. One

of these corresponded to the sachem among northern tribes. His

residence was the official house of the gens. He had in charge

the stores of the gens; and, in unimportant cases, he exercised

the powers of a judge. The other officer was the war-chief. In

times of war he commanded the forces of the gens. In times of

peace he was, so to speak, the sheriff of the gens.

The next division of the tribe was the

phratry—the word properly meaning a brotherhood. Referring

to the outline below, we notice that the eight gentes were

reunited into two phratries. Mr. Morgan tells us that the

probable origin of phratries was from the subdivision of an

original gens. Thus a tradition of the Seneca Indians affirms

that the Bear and the Deer gentes were the original gentes of

that tribe.15 In process of time

they split up into eight gentes, which would each have all the

rights and duties of an original gens—but, for certain

purposes, they were still organized into two divisions.

|

TRIBE. |

First Phratry,

or

Brotherhood. |

Bear

Wolf

Beaver

Turtle |

Gens. |

Second Phratry,

or

Brotherhood. |

Deer

Snipe

Heron

Hawk |

Gens. |

Each of these larger groups is called a

phratry. All of the Iroquois tribes were organized into

phratries, and the same was, doubtless, true of the majority of

the tribes of North America. The researches of Mr. Bandelier have

quite conclusively established the fact, that the ancient Mexican

tribe consisted of twenty gentes reunited as four phratries,

which constituted the four quarters of the Pueblo of Mexico.

It is somewhat difficult to understand just

what the rights and duties of a phratry were. This division does

not exist in all tribes. But, as it was present among the

Mexicans, we must learn what we can of its powers. Among the

Iroquois the phratry was apparent chiefly in religious matters,

and in social games. They did not elect any war-chief. The

Mexican phratry was largely concerned with military matters. The

forces of each phratry went out to war as separate divisions.

They had their own costumes and banners. The four phratries chose

each their war-chief, who commanded their forces in the field,

and who, as commander, was the superior of the war-chiefs of the

gentes.

In time of peace, they acted as the executors

of tribal justice. They belonged to the highest grade of

war-chiefs in Mexico—but there was nothing hereditary about

their offices. They were strictly elective, and could be deposed

for cause. They were in no case appointed by a higher authority.

One of these chiefs was always elected to fill the office of

"Chief of Men;"16 and, in cases

of emergency, they could take his place—but this would be

only a temporary arrangement.

Ascending the scale, the next term of the

series is the tribe. The Spanish writers took notice of a tribe,

but failed to notice the gens and phratry. This is not to be

considered a singular thing. The Iroquois were under the

observation of our own people two hundred years before the

discovery was made in reference to them. "The existence among

them of clans, named after animals, was pointed out at an early

day, but without suspecting that it was the unit of a social

system upon which both the tribe and the confederacy rested."17 But, being ignorant of this fact,

it is not singular that they made serious mistakes in their

description of the government.

We now know that the Mexican tribe was

composed of an association of twenty gentes, that each of these

gens was an independent unit, and that all of its members stood

on an equal footing. This, at the outset, does away with the idea

of a monarchy. Each gens would, of course, have an equal share in

the government. This was effected by means of a council composed

of delegates from each gens. There is no doubt whatever of the

existence of this council among the Mexicans. "Every tribe in

Mexico and Central America, beyond a reasonable doubt, had its

council of chiefs. It was the governing body of the tribe, and a

constant phenomenon in all parts of aboriginal America."18 The Spanish writers knew of the

existence of this council, but mistook its function. They

generally treat of it as an advisory board of ministers appointed

by the "king."

Each of the Mexican gens was represented in

this council by a "Speaking Chief," who, of course was elected by

the gens he represented. All tribal matters were under the

control of this council. Questions of peace and war, and the

distribution of tribute, were decided by the council. They also

had judicial duties to perform. Disputes between different gentes

were adjusted by them. They also would have jurisdiction of all

crimes committed by those unfortunate individuals who were not

members of any gens, and of crimes committed on territory not

belonging to any gens, such as the Teocalli, Market-place, and

Tecpan.

The council must have regular stated times of

meeting; they could be called together at any time. At the time

of Cortez's visits they met daily. This council was, of course,

supreme in all questions coming before it; but every eighty days

there was a council extraordinary. This included the members of

the council proper, the war-chiefs of the four phratries, the

war-chiefs of the gentes, and the leading medicine men. Any

important cause could be reserved for this meeting, or, if agreed

upon, a reconsideration of a cause could be had. We must

understand that the tribal council could not interfere in any

matter referring solely to a gens; that would be settled by the

gens itself.

The important points to be noticed are, that

it was an elective body, representing independent groups, and

that it had supreme authority. But the tribes needed officers to

execute the decrees of the council. Speaking of the Northern

tribes, Mr. Morgan says, "In some Indian tribes, one of the

sachems was recognized as its head chief; and so superior in rank

to his associates. A need existed, to some extent for an official

head of the tribe, to represent it when the council was not in

session. But the duties and powers of the office were slight.

Although the council was superior in authority, it was rarely in

session, and questions might arise demanding the provisional

action of some one authorized to represent the tribe, subject to

the ratification of his acts by the council."19

This need was still more urgent among the

Mexicans; accordingly we find they elected two officials for this

purpose. It seems this habit of electing two chief executives was

quite a common one among the tribes of Mexico and Central

America. We have already noticed that the Mexican gentes elected

two such officers for their purpose. We are further told that the

Iroquois appointed two head war-chiefs to command the forces of

the confederacy.20

One of the chiefs so elected by the Mexicans

bore the somewhat singular title of "Snake-woman." He was

properly the head-chief of the Mexicans. He was chairman of the

council and announced its decrees. He was responsible to the

council for the tribute received, as far as it was applied to

tribal requirements, and for a faithful distribution of the

remainder among the gentes. When the forces of the confederacy

went out to war, he commanded the tribal forces of Mexico; but on

other occasions this duty was fulfilled by his colleague, who was

the real war-chief of the Mexicans. His title was "Chief-of-men."

This is the official who appears in history as the "King of

Mexico," sometimes, even, as "Emperor of Anahuac." The fact is,

he was one of two equal chiefs; he held an elective office, and

was subordinate to the council.

When the confederacy was formed, the command

of its forces was given to the war-chief of the Mexicans; thus he

was something more than a tribal officer. His residence was the

official house of the tribe. "He was to be present day and night

at this abode, which was the center wherein converged the threads

of information brought by traders, gatherers of tribute, scouts

and spies, as well as all messages sent to, or received from,

neighboring friendly or hostile tribes. Every such message came

directly to the 'Chief-of-men,' whose duty it was, before acting,

to present its import to the 'Snake-woman,' and, through him,

call together the council." He might be present at the council,

but his presence was not required, nor did his vote weigh any

more than any other member of the council, only, of course, from

the position he occupied, his opinion would be much respected. He

provided for the execution of the council's conclusions. In case

of warp he would call out the forces of the confederacy for

assistance. As the procurement of substance by means of tribute

was one of the great objects of the confederacy, the gathering of

it was placed under the control of the war-chief, who was

therefore the official head of the tribute-gatherers.

We have thus very imperfectly and hastily

sketched the governmental organization of the Mexican tribe. It

is something very different from an empire. It was a democratic

organization. There was not an officer in it but what held his

office by election. This, to some, may seem improbable, because

the Spaniards have described a different state of things. We have

already mentioned one reason why they should do so—that was

their ignorance of Indian institutions. We must also consider the

natural bias of their minds. The rule of Charles the V was any

thing but liberal. It was a part of their education to believe

that a monarchical form of government was just the thing; they

were accordingly prepared to see monarchical institutions,

whether they existed or not.

Then there was the perfectly natural

disposition to exaggerate their achievements. To spread in Europe

the report that they had subverted a powerfully organized

monarchy, having an emperor, a full line of nobles, orders of

chivalry, and a standing army, certainly sounded much better than

the plain statement that they had succeeded in disjointing a

loosely connected confederacy, captured and put to death the head

war chief of the principal tribe, and destroyed the communal

buildings of their pueblo.

We must not forget that, from an Indian point

of view, the confederacy was composed of rich and powerful

tribes. This is especially true of the Mexicans. The position

they held, from a defensive standpoint, was one of the strongest

ever held by Indians. They received a large amount of tribute

from subject tribes, along with the hearty hatred of the same.

From the time Cortez landed on the shore he had heard accounts of

the wealth, power, and cruelty of the Mexicans. When he arrived

before Mexico the "Chief-of-men," Montezuma, as representative of

tribal hospitality, went forth to meet him, extending "unusual

courtesies to unusual, mysterious, and therefore dreaded,

guests." We may well imagine that he was decked out in all the

finery his office could raise, and that he put on as much style

and "court etiquette" as their knowledge and manner of life would

stand.

The Spaniards immediately concluded that he

was king, and so he was given undue prominence. They subsequently

learned of the council, and recognized the fact that it was

really the supreme power. They learned of the office of

"Snake-woman," and acknowledged that his power was equal to that

of the "Chief-of-men." They even had some ideas of phratries and

gentes. But, having once made up their minds that this was a

monarchy, and Montezuma the monarch, they were loath to change

their views, or, rather, they tried to explain all on this

supposition, and the result is the confused and contradictory

accounts given of these officials and divisions of the people.

But every thing tending to add glory to the "Empire of Montezuma"

was caught up and dilated upon. And so have come down to us the

commonly accepted ideas of the government of the ancient

Mexicans.

That these views are altogether erroneous is

no longer doubted by some of the very best American scholars. The

organization set forth in this chapter is one not only in accord

with the results obtained by the latest research in the field of

ancient society, but a careful reading of the accounts of the

Spanish writers leads to the same conclusions.21 In view of these now admitted facts,

it seems to us useless to longer speak of the government of the

Mexicans as that of an empire.

We have as yet said nothing of the league or

confederacy of the three tribes of Mexico, Tezcuco, and Tlacopan;

nor is it necessary to dwell at any great length on this

confederacy now. They were perfectly independent of each other as

regards tribal affairs; and for the purpose of government, were

organized in exactly the same way as were the Mexicans. The

stories told of the glories, the riches, and power of the kings

of Tezcuco, if any thing, outrank those of Mexico. We may dismiss

them as utterly unreliable. Tribal organization resting on

phratries and gentes, and the consequent government by the

council of the tribe was all the Spaniards found. These three

tribes, speaking dialects of the same stock language, inhabiting

contiguous territory, formed a league for offensive and defensive

purposes. The commander-in-chief of the forces raised for this

purpose was the "Chief-of-men" of the Mexicans.

We have confined our researches to the

Mexicans. Mr. Bandelier, speaking of the tribes of Mexico,

remarks: "There is no need of proving the fact that the several

tribes of the valley had identical customs, and that their

institutions had reached about the same degree of development."

Or if such proofs were needed, Mr. Bancroft has furnished them.

So that this state of society being proven among the Mexicans, it

may be considered as established among the Nahua tribes. Neither

is there any necessity of showing that substantially the same

state of government existed among the Mayas of Yucatan. This is

shown by their architecture, by their early traditions, and by

many statements in the writings of the early historians. These

can only be understood and explained by supposing the same social

organization existed among them as among the Mexicans.

But this does not relegate these civilized

nations to savagism. On the other hand, it is exactly the form of

government we would expect to find among them. They were not

further along than the Middle Status of barbarism. They were

slowly advancing on the road that leads to civilization, and

their form of government was one exactly suited to their needs,

and one in keeping with their state of architecture. When we gaze

at the ruins of their material structures, we must consider that

before us are not the only ruins wrought by the Spaniards; the

native institutions were doomed as well. Traces of this early

state of society are, however, still recoverable, and we must

study them well to learn their secret.

We have yet before us a large field to

investigate; that is, the advance made in the arts of living

among these people. This is one of the principal objects of our

present research. We are here slightly departing from the

prehistoric field, and entering the domain of history. But the

departure is justifiable, as it serves to light up an extensive

field, that is, the manner of life among the civilized nations

just before the coming of the Spaniards. And first we will

examine their customs in regard to property. We have in a former

chapter reverted to the influence of commerce and trade in

advancing culture. The desire for wealth and property which is

such a controlling power to-day was one of the most efficient

agents in advancing man from savagism to civilization. The idea

of property, which scarcely had an existence during that period

of savagism, had grown stronger with every advance in culture.

"Beginning in feebleness, it has ended in becoming the master

passion of the human mind."

The property of savages is limited to a few

articles of personal use; consequently, their ideas as to its

value, and the principles of inheritance, are feeble. They can

scarcely be said to have any idea as to property in lands, though

the tribe may lay claim to certain hunting-grounds as their own.

As soon as the organization of gens arose, we can see that it

would affect their ideas of property. The gens, we must remember,

was the unit of their social organization.

They had common rights, duties, and

privileges, as well as common supplies; and hence the idea arose

that the property of the members of a gens belonged to the gens.

At the death of an individual, his personal property would be

divided among the remaining members of the gens. "Practically,"

says Mr. Morgan, "they were appropriated by the nearest of kin;

but the principle was general that the property should remain in

the gens."22 That this is a true

statement there is not the shadow of a doubt. This was the

general rule of inheritance among the Indian tribes of North

America. As time passed on, and the tribes learned to cultivate

the land, some idea of real property would arise—but not of

personal ownership.

This is quite an important topic; because,

when we read of lords with great estates, we are puzzled to know

how to reconcile such statements with what we now know of the

nature of Mexican tribal organization. Mr. Bandelier has lately

gone over the entire subject. He finds that the territory on

which the Mexicans originally settled was a marshy expanse of

land which the surrounding tribes did not value enough to

claim.

This territory was divided among the four

gentes of the tribe. As we have already seen, each of these four

gentes subsequently split up into other independent gentes until

there were twenty in all. Each of these gens held and possessed a

portion of the original soil. This division of the soil must have

been made by tacit consent. The tribe claimed no ownership of

these tracts, still less did the head-chief. Furthermore, the

only right the gentes claimed in them was a possessory one. "They

had no idea of sale or barter, or conveyance, or alienation." As

the members of a gens stood on equal footing, this tract would be

still further divided for individual use. This division would be

made by the council of the gens. But we must notice the

individual acquired no other right to this tract of land than a

right to cultivate it—which right, if he failed to improve,

he lost. He could, however, have some one else to till it for

him. The son could inherit a father's right to a tract.

We have seen that the Mexicans had a great

volume of tribal business to transact, which required the

presence of an official household at the tecpan. Then the proper

exercise of tribal hospitality required a large store of

provisions. To meet this demand, certain tracts of the territory

of each gens were set aside to be worked by communal labor. Then,

besides the various officers of the gens, and the tribe, who, by

reason of their public duties, had no time to till the tracts to

which, as members of a gens, they would be entitled, had the same

tilled for them by communal labor. This was not an act of

vassalage, but a payment for public duties.

This is a very brief statement of their

customs as regards holding of lands. It gives us an insight into

the workings of ancient society. It shows us what a strong

feature of this society was the gens, and we see how necessary it

is to understand the nature of a gens before attempting to

understand ancient society. We see that, among the civilized

nations of Mexico and Central America, they had not yet risen to

the conception of ownership in the soil. No chief, or other

officer, held large estates. The possessory right in the soil was

vested in the gens composing the tribe, and they in turn granted

to individuals certain definite lots for the purpose of culture.

A chief had no more right in this direction than a common

warrior. We can easily see how the Spaniards made their mistake.

They found a community of persons holding land in common, which

the individuals could not alienate. They noticed one person among

them whom the others acknowledged as chief. They immediately

jumped to the conclusion that this chief was a great "lord," that

the land was a "feudal estate," and that the persons who held it

were "vassals" to the aforesaid "lord."23

We must now consider the subject of laws, and

the methods of enforcing justice amongst the civilized nations.

The laws of the Mexicans, like those of most barbarous people,

are apt to strike us as being very severe; but good reasons,

according to their way of thinking, exist for such severity. The

gens is the unit of social organization; which fact must be

constantly borne in mind in considering their laws. In civilized

society, the State assumes protection of person and property;

but, in a tribal state of society, this protection is afforded by

the gens. Hence, "to wrong a person was to wrong his gens; and to

support a person was to stand behind him with the entire array of

his gentile kindred."

The punishment for theft varied according to

the value of the article stolen. If it were small and could be

returned, that settled the matter. In cases of greater value it

was different. In some cases the thief became bondsman for the

original owner. In still others, he suffered death. This was the

case where he stole articles set aside for religion—such as

gold and silver, or captives taken in war; or, if the theft were

committed in the market-place. Murder and homicide were always

punished with death. According to their teaching, there was a

great gulf between the two sexes. Hence, for a person of one sex

to assume the dress of the other sex was an insult to the whole

gens—the penalty was death. Drunkenness was an offense

severely punished—though aged persons could indulge their

appetite, and, during times of festivities, others could. Chiefs

and other officials were publicly degraded for this crime. Common

warriors had their heads shaved in punishment.

These various penalties necessarily suppose

judicial officers to determine the offense and decree the

punishment. Having established, on a satisfactory basis, the

Mexican empire, the historians did not scruple to fit it out with

the necessary working machinery of such an organization.

Accordingly we are presented with a judiciary as nicely

proportioned as in the most favored nations of to-day. But when,

under the more searching light of modern scholarship, this empire

is seen to be something quite different, we find the whole

judicial machinery to be a much more simple affair.

Not much need be added on this point to what

we have already mentioned. Each gens, through its council, would

regulate its own affairs, and would punish all offenses against

the law committed by one of its members against another. Of

necessity the decision of this council had to be final. There was

no appeal from its decision. The council of the tribe had

jurisdiction in all other cases—such as might arise between

members of different gentes, or among outcasts not connected with

any gens, or such as were committed on territory not belonging to

any gens.

For this work, the twenty chiefs composing the

council were subdivided into two bodies, sitting simultaneously

in the different halls of the tecpan. This division was for the

purpose of greater dispatch in business. They did not form a

higher and lower court, with power of the one to review the

decisions of the other. They were equal in power and the

decisions of both were final. The decision of the council, when

acting in a judicial capacity, would be announced by their

foreman, who was, as we have seen, the head-chief of the

Mexicans—the Snake-woman. It is for this act that the

historian speaks of him as the supreme judge, and makes him the

head of judicial authority.24 His

decisions were, of course, final, not because he made them, but

because they were the conclusions of the council.

The "Chief-of-men," the so-called "king," did

not properly have any judicial authority. He was their war-chief,

and not a judge; but from the very nature of his office he had

some powers in this direction. As commander-in-chief, he

possessed authority to summarily punish (with death, if

necessary) acts of insubordination and treachery during war. It

was necessary to clothe him with a certain amount of

discretionary power for the public good. Thus, the first runner

that arrived from the coast with news of the approach of the

European ships was, by the order of Montezuma, placed in

confinement. "This was done to keep the news secret until the

matter could be investigated, and was therefore a preliminary

measure of policy." Placed at the tecpan as the official head of

the tribe, he had power to appoint his assistants. But this power

to appoint implied equal power to remove, and to punish.25

This investigation into their laws and methods

of enforcing them, carries us to the conclusion already arrived

at. It is in full keeping with what we would expect of a people

in the Middle Status of barbarism. We also see how little real

foundation there is for the view that this was a monarchy. There

is no doubt but that the pueblo of Mexico was the seat of one of

the largest and most powerful tribes, and the leading member of

one of the most powerful confederacies that had ever existed in

America.

It may be of interest for us to inquire as to

what was the real extent of this power, and the means employed by

the Mexicans to maintain this power; also how they had succeeded

in attaining the same. They were not by nature more gifted than

the surrounding tribes. The valley of Mexico is an upland basin.

It is oval in form, surrounded by ranges of mountains, rising one

above the other, with depressions between. The area of the valley

itself is about sixteen hundred square miles. The Mexicans were

the last one of the seven kindred tribes who styled themselves,

collectively, the Nahuatlacs. We treat of them as the Nahuas.

The Nahuas on the north and the Mayas on the

south included the civilized nations. When the Mexicans arrived

in this valley, they found the best situations already occupied

by other tribes of their own family. To escape persecution from

these, they fled into the marsh or swamp which then covered the

territory which they subsequently converted into their

stronghold. Here on a scanty expanse of dry soil, surrounded by

extensive marshes, they erected their pueblo. Being few in

numbers they were overlooked as insignificant, and thus they had

a chance to improve their surroundings. They increased the area

of dry land by digging ditches, and throwing the earth from the

same on the surrounding surface, and thus elevated it. In

reality, in the marshes that surrounded their pueblo was their

greatest source of strength. "They realized that while they might

sally with impunity, having a safe retreat behind them, an attack

upon their position was both difficult and dangerous for the

assailant." They were, therefore, strong enough for purposes of

defense. But they wished to open up communication with the tribes

living on the shore of the great marsh in the midst of which they

had their settlement. For this purpose they applied to their near

and powerful neighbors, the Tecpanics, for the use of one of the

springs on their territory, and for the privilege of trade and

barter in their market. This permission was given in

consideration that the Mexicans become the weaker allies of the

Tecpanics, that is, pay a moderate tribute and render military

assistance when called upon.

The Pueblo of Mexico now rapidly increased in

power. Communication being opened with the mainland, it was

visited by delegates from other tribes, and especially by

traders. They fully perceived the advantages of their location

and improved the same. By the erection of causeways, they

entirely surrounded their pueblo with an artificial pond of large

extent. To allow for the free circulation of the water, sluices

were cut, interrupting these causeways at several places. Across

these openings wooden bridges were placed which could be easily

removed in times of danger.

Thus it was that they secured one of the

strongest defensive positions ever held by Indians. The Tecpanics

had been the leading power in the valley, but the Mexicans now

felt themselves strong enough to throw off the yoke of tribute to

which they were subject. In the war that ensued the power of the

Tecpanics was broken, and the Mexicans became at once one of the

leading powers of the valley. We must notice, however, that the

Mexicans did not gain any new territory, except the locality of

their spring. Neither did they interfere at all in the government

of the Tecpanics. They simply received tribute from them.

Once started on their career of conquest, the

Mexicans, supported by allies, sought to extend their power. The

result was that soon they had subdued all of the Nahua tribes of

the valley except one, that was a tribe located at Tezcuco. This

does not imply that they had become masters of the territory of

the valley. When a modern nation or state conquers another, they

often add that province to their original domain, and extend over

it their code of laws. This is the nature of the conquests of

ancient Rome. The territory of the conquered province became part

of the Roman Empire. They became subject to the laws of Rome.

Public, works were built under the direction of the conquerors,

and they were governed from Rome or by governors appointed from

there.

Nothing of this kind is to be understood by a

conquest by the Mexicans, and it is necessary to understand this

point clearly. When they conquered a tribe, they neither acquired

nor claimed any right to or power over the territory of the

tribe. They did not concern themselves at all with the government

of the tribe. In that respect the tribe remained free and

independent. No garrisons of troops were stationed in their

territory to keep them in subjection; no governors were appointed

to rule over them. What the Mexicans wanted was tribute, and in

case of war they could call on them for troops. Secure in their

pueblo surrounded by water, they could sally out on the less

fortunate tribes who chose to pay tribute rather than to be

subject to such forays.

Instead of entering into a conflict with the

tribe at Tezcuco, the result of which might have been doubtful, a

military confederacy was formed, into which was admitted the

larger part of the old Tecpanic tribe that had their chief pueblo

at Tlacopan. The definite plan of this confederacy is unknown.

Each of the three tribes was perfectly independent in the

management of its own affairs. Each tribe could make war on its

own account if it wished, but in case it did not feel strong

enough alone, it could call on the others for assistance. When

the force of the confederacy went out to war, the command was

given to the war chief of the Mexicans, the "Chief-of-men."

If a member of the confederacy succeeded in

reducing by its own efforts a tribe to tribute, it had the full

benefit of such conquest. But when the entire confederacy had

been engaged in such conquest, the tribute was divided into five

parts, of which two went to Mexico, two to Tezcuco, and one to

Tlacopan. This co-partnership for the purpose of securing tribute

by the three most powerful tribes of the valley, under the

leadership of Mexico, was formed about the year 1426, just about

one hundred years from the date of the first appearance of the

Mexicans in the valley.

From this time to the date of the Spanish

conquest in 1520, the confederate tribes were almost constantly

at war with the surrounding Indians, and particularly with the

feeble village Indians southward from the valley of Mexico to the

Pacific, and thence eastward well towards Guatemala. They began

with those nearest in position, whom they overcame, through

superior numbers, and concentrated action, and subjected to

tribute. These forays were continued from time to time for the

avowed object of gathering spoil, imposing tribute and capturing

prisoners for sacrifice, until the principal tribes within the

area named, with some exceptions, were subdued and made

tributary.26

The territory of these tribes, thus subject to

tribute, constitutes what is generally known as the Mexican

Empire.27 But, manifestly, it is

an abuse of language to so designate this territory. No attempt

was made for the formation of a State which would include the

various groups of aborigines settled in the area tributary to the

confederacy. "No common or mutual tie connected these numerous

and diverse tribes," excepting hatred of the Mexican confederacy.

The tribes were left independent under their own chiefs. They

well knew the tribute must be forthcoming, or else they would

feel the weight of their conquerors' displeasure. But such a

domination of the strong over the weak, for no other reason than

to enforce an unwilling tribute, can never form a nation, or an

empire.28 These subject tribes,

held down by heavy burdens—inspired by enmity, ever ready

to revolt—gave no new strength to the confederacy: they

were rather an element of weakness. The Spaniards were not slow

to take advantage of this state of affairs. The tribes of Vera

Cruz, who could have imposed an almost impassable barrier to

their advance through that section, were ready to welcome them as

deliverers.29 The Tlascaltecans,

though never made tributary to the Mexicans, had to wage almost

unceasing war for fifty years preceding the coming of the

Spaniards. Without their assistance, Cortez would never have

passed into history as the conqueror of Mexico.

A word as to the real power of the Mexicans.

Their strength lay more in their defensive position than any

thing else. As we have just stated, the entire forces of the

confederacy were unable to subject the Tlascaltecans, the Tarasca

of Michhuacan were fully their equal in wealth and power. The

most disastrous defeat that ever befell the forces of the

confederacy was on the occasion of their attack upon this

last-named people in 1479. They fled from the battle-field in

consternation, and never cared to renew the attempt. As to the

actual population of the Pueblo of Mexico, the accounts are very

much at variance. Mr. Morgan, after taking account of their

barbarous condition of life—without flocks and herds, and

without field agriculture, but also considering the amount of

tribute received from other tribes—considers that an

estimate of two hundred and fifty thousand inhabitants in the

entire valley would be an excessive number. Of these he would

assign thirty thousand to the Pueblo of Mexico.30

This is but an estimate. In this connection we

are informed, that, when the forces of the confederacy marched

against Michhuacan, as just stated, they counted their forces,

and found them to be twenty-four thousand men. This includes the

forces of the three confederate tribes, and their allies in the

valley, and would indicate a population below Mr. Morgan's

estimate. The Spanish writers have left statements as to the

population of Mexico which are, evidently, gross exaggerations.

The most moderate estimate is sixty thousand inhabitants; but the

majority of the writers increase this number to three hundred

thousand.

The main occupation of the Aztecs, then, was

to enforce the payment of tribute. From the limited expanse of

territory at the disposal of the Mexicans, and the unusually

large number of inhabitants for an aboriginal settlement, as well

as the natural inclination of the Mexicans, they were obliged to

draw their main supplies from tributary tribes. It is human for

the strong to compel the weak to serve them. The inhabitants of

North America were not behind in this respect.31 This is especially true of the

civilized tribes of Mexico and Central America. The confederacy

of the three most powerful tribes of Mexico was but a

copartnership for the avowed purpose of compelling tribute from

the surrounding tribes, and they were cruel and merciless in

exacting the same.

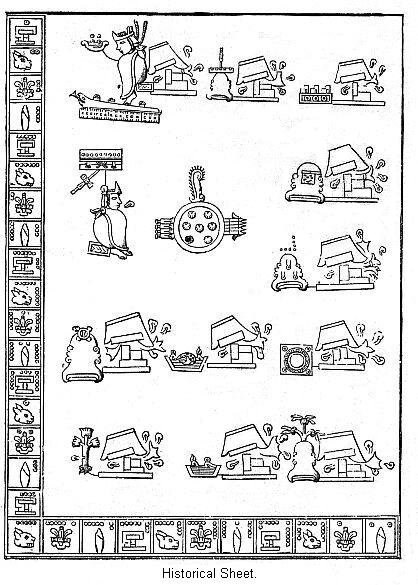

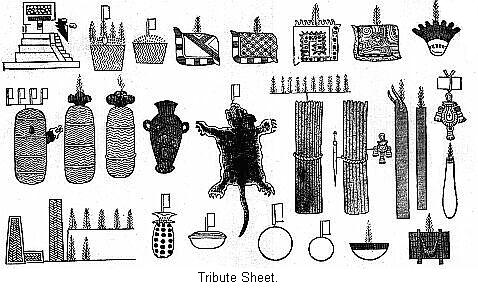

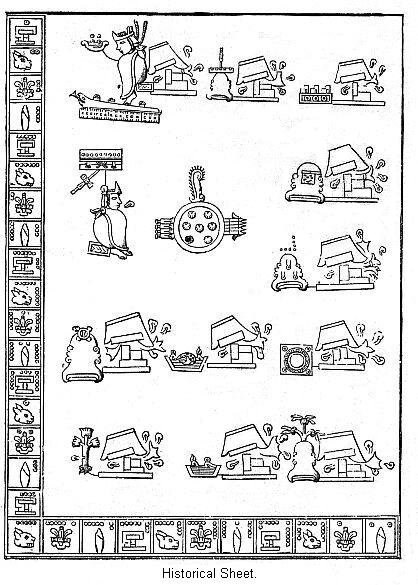

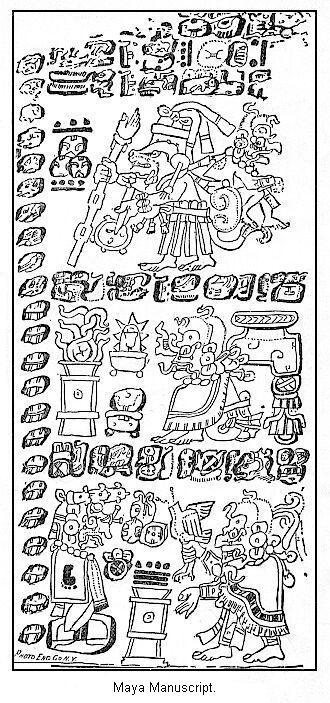

Our information in regard to this tribute is

derived almost entirely from a collection of picture writings,

known as the Mendoza collection, which will be described more

particularly when we describe their picture writings. The

confederacy was never at a loss for an excuse to pounce upon a

tribe and reduce them to tribute. Sometimes the tribe marked out

for a prey, knowing their case to be hopeless, submitted at once

when the demand was made; but, whether they yielded with or

without a struggle, the result was the same—that is, a

certain amount of tribute was imposed on them. This tribute

consisted of articles which the tribe either manufactured, or was

in situation to acquire by means of trade or war; but, in

addition to this, it also included the products of their limited

agriculture.

The same distribution of land obtained among

all the civilized tribes that we have already sketched among the

Mexicans. So, a portion of the territory of each conquered tribe

would be set aside to be cultivated for the use of the

confederacy. But, as the tribe did not have any land of its own,

except for some official purpose, this implies that each gens

would have to set aside a small part of its territory for such

purpose. Such lots Mr. Bandelier calls tribute lots. These were

worked by the gentes for the benefit of the Mexicans. It is to be

noticed right here, that the Mexicans did not claim to own or

control the land; this right remained in the gentes of the

conquered tribe.

The miscellaneous articles demanded were

generally such that they bore some relation to the natural

resources of the pueblo. For instance: pueblos along the coast,

in the warm region of country, had to furnish cotton cloth, many

thousand bundles of fine feathers, sacks of cocoa, tiger-skins,

etc. In other, and favorable locations for such products, the

pueblos had to furnish such articles as sacks of lime, reeds for

building purposes, smaller reeds for the manufacture of

darts.

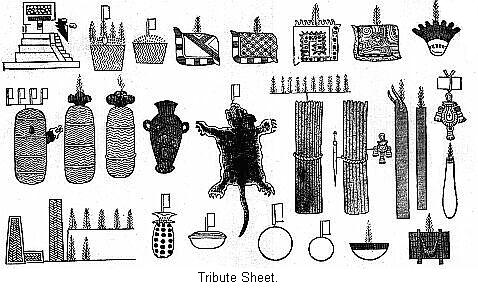

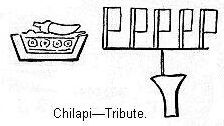

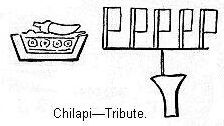

These facts are ascertained in the Mendoza

collection. We are given there the pictorial symbol, or

coat-of-arms, of various pueblos; also, a pictorial

representation of the tribute they wore expected to pay. The

plate is a specimen of their tribute rolls. The pueblos paying it

are not, however, shown. Considerable can be learned from a study

of this collection —such, for instance, as that the Pueblo

of Chala had to pay a tribute of forty little bells, and eighty

copper ax blades.32 And, in

another place, we learn that the Pueblo of Yzamatitan was

tributary to eight thousand reams of paper. The articles are here

pictured forth; the number is indicated by the flags, feathers,

etc. The tribute of provisions consisted of such articles as

corn, beans, cocoa, red-pepper, honey, and salt—amounting

in all, according to this collection33 to about six hundred thousand bushels.

Still it will not do to place too great a reliance on picture

records. The number of tributary pueblos must have been

constantly changing. The quantity of articles intended for

clothing was certainly very great. A moderate quantity of gold

was also collected from a few pueblos, where this was

obtainable.

The collection of this tribute was one of the

most important branches of government among the Mexicans. The

vanquished stood in peril of their lives if they failed to keep

their part of the contract. In the first place, the Mexicans took

from each subject tribe hostages for the punctual payment of

tribute. These hostages were taken to the Pueblo of Mexico, and

held there as slaves; their lives were forfeited if the tribute

was refused.34 But special

officers were also assigned to the subject tribes, whose duty it

was to see that the tribute was properly gathered and transmitted

to Mexico. These stewards or tribute gatherers, are the officers

that the early writers mistook for governors. Their sole

business, however, had to do with the collection of the tribute,

and they did not interfere at all in the internal affairs of the

tribe.

Where the forces of the confederacy had

conquered a tribe, but one steward was required to tend to the

tribute, but each of the confederate tribes sent their

representative to such pueblos as had become their own prey, and

as sometimes occurred, one pueblo paid tribute to each of the

confederate tribes, it had to submit to the presence among them

of three separate stewards.

We can easily enough see that it required men

of ability to fill this position. They were to hold their

residence in the midst of a tribe who were conquered, but held in

subjection only by fear. To these people they were the constant

reminder of defeat and disgrace. They were expected to watch them

closely and report to the home tribe suspicious movements or

utterances that might come to their notice. We need not wonder

that these stewards were the tokens of chiefs. It was a part of

their duty to superintend the removal of the tribute from the

place where gathered to the Pueblo of Mexico. The tribe paying

tribute were expected to deliver it at Mexico, but under the

supervision of the steward. Arrived at Mexico the tribute was

received, not by the so-called king, the Chief-of-men, but by the

Snake-woman, or an officer to whom this personage delegated his

authority. This officer was the chief steward, and made the final

division of the tribute. We are not informed as to details of

this division. A large part of it was reserved for the use of the

tribal government. It was upon this store that the Chief-of-men

could draw when supplies were needed for tribal hospitality or

for any special purpose. The stores required for the temple, its

priests and keepers were gathered from this source. The larger

division must have gone direct to the stewards of the gentes, who

would set some aside for their official uses, some for religion

or medicine, but the larger part would be divided among the

members of the gentes.

In our review of the social system of the

Mexicans we have repeatedly seen how the organization of gentes

influenced and even controled all the departments of their social

and political system. One of the cardinal principles, we must

remember, is that all the members of a gens stand on an equal

footing. In keeping with this we have seen that all were trained

as warriors; yet the great principle of the division of labor was

at work. Some filled in their leisure during times of peace by

acting as traders; others became proficient in some branch of

work, such as feather work, or making gold and silver ornaments.

Yet under a gentile system of society, persons practising such

callings could never become very rich or proficient, simply

because, being members of different gentes, there could not be

that cooperation and united efforts among workmen in these

various trades and callings that is necessary to advance them to

the highest proficiency. It required the breaking up of the

gentes and substituting for that group a smaller one, our modern

family, as the unit of social organization, before great progress

could be made.

From what we have just said it follows that it

is not at all likely that there was any great extremes in the

condition of the people. No very wealthy or extremely poor

classes. This brings us to consider the condition of trade and

commerce among them. They had properly no such a thing as money,

so their commerce must have consisted of barter or trade and

exchange. Some authorities assert quite positively that they had

money, and mention as articles used for such purposes grains of

cacao, "T" shaped pieces of tin or copper, and quills of gold

dust.35 But Mr. Bandelier has

shown that the word barter properly designates the transactions

where such articles passed. But this absence of money shows us at

once that the merchants of Mexico were simply traders who made

their living by gathering articles from a distance to exchange

for home commodities.

We are given some very entertaining accounts

of the wealth and magnificence of the "merchant princes of

Mexico."36 It needs but a

moment's consideration of the state of society to show how little

foundation there is for such accounts. Mr. Bancroft also tells us

that "throughout the Nahua dominions commerce was in the hands of

a distinct class, educated for their calling, and everywhere

honored by the people and by kings. In many regions the highest

nobles thought it not disgraceful to engage in commercial

pursuits."

Though we do not believe there is any

foundation for this statement, yet trading is an important

proceeding among sedentary tribes. "The native is carried over

vast distances, from which he returns with a store of knowledge,

which is made a part of his mythology and rites, while his

personal adventures become a part of the folk lore."37 It was their principal way of learning

of the outside world. It was held in equally high esteem among

the Mexicans. Such an expedition was not in reality a private,

but a tribal undertaking. Its members not only carried into

distant countries articles of barter, but they also had to

observe the customs, manners, and resources of the people whom

they visited. Clothed with diplomatic attributes, they were often

less traders than spies. Thus they cautiously felt their way from

tribe to tribe, from Indian fair to Indian fair, exchanging their

stuff for articles not produced at home, all the while carefully

noting what might be important to their own tribe. It was a

highly dangerous mission; frequently they never returned, being

waylaid or treacherously butchered even while enjoying the

hospitality of a pueblo in which they had been bartering.

We may be sure the setting out of such an

expedition would be celebrated in a formal manner.38 The safe return was also an important

and joyful event. The reception was almost equal to that afforded

to a victorious war-party. After going to the temple to adore the

idol, they were taken before the council to acquaint them with

whatever they had learned of importance on their trip. In

addition to this, their own gens would give them appropriate

receptions. From the nature of things but little profit remained

to the trader. They had no beasts of burden, and they must bring

back their goods by means of carriers; and the number of such men

were limited. Then their customs demanded that the most highly

prized articles should be offered up for religious purposes;

besides, the tribe and the gens each came in for a share. But the

honors given were almost as great as those won in war.

The Mexicans had regular markets. This, as we

have already stated, was on territory that belonged to the tribe;

not to any one gens alone. Hence the tribal officers were the

ones to maintain order. The chiefs of the four phratries were

charged with this duty. The market was open every day, but every

fifth was a larger market.39 They

do not seem to have had weights, but counted or measured their

articles. In these markets, or fairs, which would be attended by

traders from other tribes, who, on such occasions, were the

guests of the Mexicans, and lodged in the official house, would

be found the various articles of native manufacture: cloth,

ornaments, elaborate featherwork, pottery, copper implements and

ornaments, and a great variety of articles not necessary to

enumerate.

We must now briefly consider their arts and

manufactures. Stone was the material principally used for their

weapons and implements. They were essentially in their Stone Age.

Their knives, razors, lancets, spear and arrowheads were simply

flakes of obsidian. These implements could be produced very

cheaply, but the edge was quickly spoiled. Axes of different

varieties of flint were made. They also used flint to carve the

sculptured stones which we have described in the preceding

chapter. They also had some way of working these big blocks of

stone used in building. But they were not unacquainted with

metals—the ornamental working of gold and silver had been

carried to quite a high pitch. Were we to believe all the

accounts given us of their skill in that direction, we would have

to acknowledge they were the most expert jewelers known. How they

cast or moulded their gold ornaments is unknown. They were also

acquainted with other metals, such as copper, tin, and lead. But

we can not learn for what purpose they used lead or tin, or where

they obtained it.40

Cortez, in one of his letters, speaks of the

use of small pieces of tin as money. But we have already seen

that the natives had not risen to the conception of money. They

certainly had copper tools, and bronze ones. It seems, however,

that their bronze was a natural production and not an artificial

one—that is to say, the ores of copper found in Mexico

contain more or less gold, silver, and tin. So, if melted, just

as nature left them, the result would be the production of

bronze.41 They were then ignorant

of the knowledge of how to make bronze artificially. This shows

us that they had not attained to a true Bronze Age; and yet the

discovery could not have been long delayed. Sooner or later they

would have found out that tin and copper melted together would

produce the light copper that experience had taught them was the

most valuable.

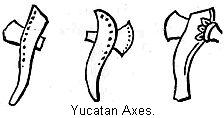

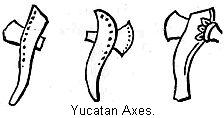

The most important tool they made of copper

was the ax. The ax, in both Mexico and Yucatan, was made as

represented in this illustration. From their shape and mode of

hafting them, we see at once they are simply models of the stone

ax; and this recalls what we learned of the Bronze Age in Europe.

At first they contented themselves with copying the forms in

stone.

Nature, everywhere, conducts her children by

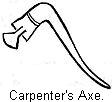

the same means to the same ends. This form of ax is a

representation of a carpenter's hatchet. The next cut is from the

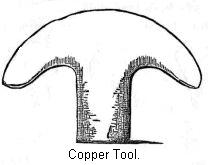

Mendoza collection, and represents a carpenter at work. He holds

one of these hatchets in his hand, and is shaping a stick of

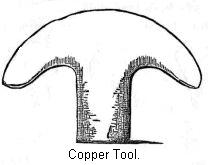

timber. The other cut represents a form of copper tool found in

Oaxaca, where they were once used in abundance. The supposition

is that this implement was used for agricultural

purposes—probably as a hoe. The pieces of T-shaped copper

said to have been used as money, are diminutive forms of this

same tool. The statement is sometimes made that they had a way of

hardening copper. "This," says Mr. Valentine, "is a hypothesis,

often noted and spoken of, but which ranges under the efforts

made for explaining what we have no positive means to verify or

to ascertain." The presence of metals necessarily implies some

skill in mining; but their ability to mine was certainly very

limited. Gold and silver were collected by washing the sands. We

do not know how copper was mined; the probabilities are that this

was done in a very superficial way. Whenever, by chance, they

discovered a vein of copper, they probably worked it to an easy

depth, and then abandoned it. M. Charney speaks of one such

locality, discovered in 1873. In this case they had made an

opening eleven feet long, five feet wide, and three feet deep. To

judge from appearances, they first heated the rock, and then

perhaps sprinkled it with water, and thus caused it to split

up.42 This is about all we can

discover of their Metallic Age. It falls very far short of the

knowledge of metallurgy enjoyed by the Europeans of the Bronze

Age; and, with the exception of working gold and silver, it was

not greatly in advance of the powers of the North American

aborigines.43 Certainly no trace

of mining has been discovered at all on the scale of the ancient

mines in Michigan.

A few words as to some of their other arts,

and we will pass on to other topics. In manufacturing native

pottery, they are spoken of as having great skill. The sedentary

Indians everywhere were well up in that sort of work.44 They knew how to manufacture cotton

cloth, as well as cloth from other articles. We have stated that

paper furnished an important article of tribute. They made

several kinds of paper. One author states that they made paper

from the membrane of trees—from the substance that grows

beneath the upper bark.45 But

they also used for this purpose a plant, called the maguey plant.

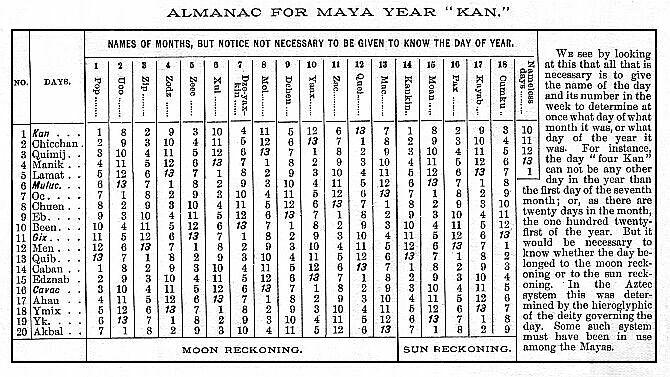

This was a very valuable plant to the aborigines, since we are