This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Irish Fairy Tales

Editor: W. B. (William Butler) Yeats

Release Date: March 25, 2010 [eBook #31763]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IRISH FAIRY TALES***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/fairytalesirish00yeatrich |

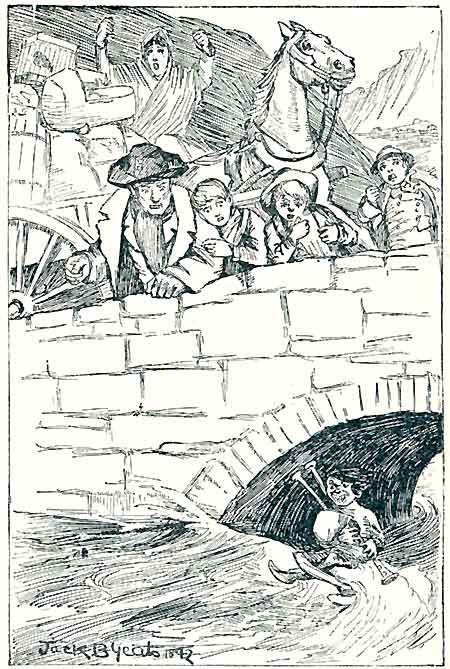

"PLAYING AWAY ON THE PIPES AS MERRILY AS IF NOTHING HAD

HAPPENED." [Page 48.

"PLAYING AWAY ON THE PIPES AS MERRILY AS IF NOTHING HAD

HAPPENED." [Page 48.

W. B. Yeats.

London, January 1892.

am often doubted when I say that the Irish peasantry still believe in fairies. People think I am merely trying to bring back a little of the old dead beautiful world of romance into this century of great engines and spinning-jinnies. Surely the hum of wheels and clatter of printing presses, to let alone the lecturers with their black coats and tumblers of water, have driven away the goblin kingdom and made silent the feet of the little dancers.[2]

Old Biddy Hart at any rate does not think so. Our bran-new opinions have never been heard of under her brown-thatched roof tufted with yellow stone-crop. It is not so long since I sat by the turf fire eating her griddle cake in her cottage on the slope of Benbulben and asking after her friends, the fairies, who inhabit the green thorn-covered hill up there behind her house. How firmly she believed in them! How greatly she feared offending them! For a long time she would give me no answer but 'I always mind my own affairs and they always mind theirs.' A little talk about my great-grandfather who lived all his life in the valley below, and a few words to remind her how I myself was often under her roof when but seven or eight years old loosened her tongue, however. It would be less dangerous at any rate to talk to me of the fairies than it would be to tell some 'Towrow' of them, as she contemptuously called English tourists, for I had[3] lived under the shadow of their own hillsides. She did not forget, however, to remind me to say after we had finished, 'God bless them, Thursday' (that being the day), and so ward off their displeasure, in case they were angry at our notice, for they love to live and dance unknown of men.

Once started, she talked on freely enough, her face glowing in the firelight as she bent over the griddle or stirred the turf, and told how such a one was stolen away from near Coloney village and made to live seven years among 'the gentry,' as she calls the fairies for politeness' sake, and how when she came home she had no toes, for she had danced them off; and how such another was taken from the neighbouring village of Grange and compelled to nurse the child of the queen of the fairies a few months before I came. Her news about the creatures is always quite matter-of-fact and detailed, just as if she dealt with any common occur[4]rence: the late fair, or the dance at Rosses last year, when a bottle of whisky was given to the best man, and a cake tied up in ribbons to the best woman dancer. They are, to her, people not so different from herself, only grander and finer in every way. They have the most beautiful parlours and drawing-rooms, she would tell you, as an old man told me once. She has endowed them with all she knows of splendour, although that is not such a great deal, for her imagination is easily pleased. What does not seem to us so very wonderful is wonderful to her, there, where all is so homely under her wood rafters and her thatched ceiling covered with whitewashed canvas. We have pictures and books to help us imagine a splendid fairy world of gold and silver, of crowns and marvellous draperies; but she has only that little picture of St. Patrick over the fireplace, the bright-coloured crockery on the dresser, and the sheet of ballads stuffed by her[5] young daughter behind the stone dog on the mantelpiece. Is it strange, then, if her fairies have not the fantastic glories of the fairies you and I are wont to see in picture-books and read of in stories? She will tell you of peasants who met the fairy cavalcade and thought it but a troop of peasants like themselves until it vanished into shadow and night, and of great fairy palaces that were mistaken, until they melted away, for the country seats of rich gentlemen.

Her views of heaven itself have the same homeliness, and she would be quite as naïve about its personages if the chance offered as was the pious Clondalkin laundress who told a friend of mine that she had seen a vision of St. Joseph, and that he had 'a lovely shining hat upon him and a shirt-buzzom that was never starched in this world.' She would have mixed some quaint poetry with it, however; for there is a world of difference[6] between Benbulben and Dublinised Clondalkin.

Heaven and Fairyland—to these has Biddy Hart given all she dreams of magnificence, and to them her soul goes out—to the one in love and hope, to the other in love and fear—day after day and season after season; saints and angels, fairies and witches, haunted thorn-trees and holy wells, are to her what books, and plays, and pictures are to you and me. Indeed they are far more; for too many among us grow prosaic and commonplace, but she keeps ever a heart full of music. 'I stand here in the doorway,' she said once to me on a fine day, 'and look at the mountain and think of the goodness of God'; and when she talks of the fairies I have noticed a touch of tenderness in her voice. She loves them because they are always young, always making festival, always far off from the old age that is coming upon her and filling her bones with aches,[7] and because, too, they are so like little children.

Do you think the Irish peasant would be so full of poetry if he had not his fairies? Do you think the peasant girls of Donegal, when they are going to service inland, would kneel down as they do and kiss the sea with their lips if both sea and land were not made lovable to them by beautiful legends and wild sad stories? Do you think the old men would take life so cheerily and mutter their proverb, 'The lake is not burdened by its swan, the steed by its bridle, or a man by the soul that is in him,' if the multitude of spirits were not near them?

W. B. Yeats.

Clondalkin,

July 1891.

have to thank Lady Wilde for leave to give 'Seanchan the Bard' from her Ancient Legends of Ireland (Ward and Downey), the most poetical and ample collection of Irish folklore yet published; Mr. Standish O'Grady for leave to give 'The Knighting of Cuculain' from that prose epic he has curiously named History of Ireland, Heroic Period; Professor Joyce for his 'Fergus O'Mara and the Air Demons'; and Mr. Douglas Hyde for his unpublished story, 'The Man who never knew Fear.'[9]

I have included no story that has already appeared in my Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (Camelot Series).

The two volumes make, I believe, a fairly representative collection of Irish folk tales.

anty M'Clusky had married a wife, and, of course, it was necessary to have a house in which to keep her. Now, Lanty had taken a bit of a farm, about six acres; but as there was no house on it, he resolved to build one; and that it might be as comfortable as possible, he selected for the site of it one of those beautiful green circles that are supposed to be the play-ground of the fairies. Lanty was warned against this; but[14] as he was a headstrong man, and not much given to fear, he said he would not change such a pleasant situation for his house to oblige all the fairies in Europe. He accordingly proceeded with the building, which he finished off very neatly; and, as it is usual on these occasions to give one's neighbours and friends a house-warming, so, in compliance with this good and pleasant old custom, Lanty having brought home the wife in the course of the day, got a fiddler and a lot of whisky, and gave those who had come to see him a dance in the evening. This was all very well, and the fun and hilarity were proceeding briskly, when a noise was heard after night had set in, like a crushing and straining of ribs and rafters on the top of the house. The folks assembled all listened, and, without doubt, there was nothing heard but crushing, and heaving, and pushing, and groaning, and panting, as if a thousand little[15] men were engaged in pulling down the roof.

'Come,' said a voice which spoke in a tone of command, 'work hard: you know we must have Lanty's house down before midnight.'

This was an unwelcome piece of intelligence to Lanty, who, finding that his enemies were such as he could not cope with, walked out, and addressed them as follows:

'Gintlemen, I humbly ax yer pardon for buildin' on any place belongin' to you; but if you'll have the civilitude to let me alone this night, I'll begin to pull down and remove the house to-morrow morning.'

This was followed by a noise like the clapping of a thousand tiny little hands, and a shout of 'Bravo, Lanty! build half-way between the two White-thorns above the boreen'; and after another hearty little shout of exultation, there was a brisk rushing noise, and they were heard no more.[16]

The story, however, does not end here; for Lanty, when digging the foundation of his new house, found the full of a kam[1] of gold: so that in leaving to the fairies their play-ground, he became a richer man than ever he otherwise would have been, had he never come in contact with them at all.

[1] Kam—a metal vessel in which the peasantry dip rushlights.

n the north of Ireland there are spinning meetings of unmarried females frequently held at the houses of farmers, called kemps. Every young woman who has got the reputation of being a quick and expert spinner attends where the kemp is to be held, at an hour usually before daylight, and on these occasions she is accompanied by her sweetheart or some male relative, who carries her wheel, and conducts her safely across the fields or along the road, as the case may be. A[18] kemp is, indeed, an animated and joyous scene, and one, besides, which is calculated to promote industry and decent pride. Scarcely anything can be more cheering and agreeable than to hear at a distance, breaking the silence of morning, the light-hearted voices of many girls either in mirth or song, the humming sound of the busy wheels—jarred upon a little, it is true, by the stridulous noise and checkings of the reels, and the voices of the reelers, as they call aloud the checks, together with the name of the girl and the quantity she has spun up to that period; for the contest is generally commenced two or three hours before daybreak. This mirthful spirit is also sustained by the prospect of a dance—with which, by the way, every kemp closes; and when the fair victor is declared, she is to be looked upon as the queen of the meeting, and treated with the necessary respect.

But to our tale. Every one knew[19] Shaun Buie M'Gaveran to be the cleanest, best-conducted boy, and the most industrious too, in the whole parish of Faugh-a-ballagh. Hard was it to find a young fellow who could handle a flail, spade, or reaping-hook in better style, or who could go through his day's work in a more creditable or workmanlike manner. In addition to this, he was a fine, well-built, handsome young man as you could meet in a fair; and so, sign was on it, maybe the pretty girls weren't likely to pull each other's caps about him. Shaun, however, was as prudent as he was good-looking; and although he wanted a wife, yet the sorrow one of him but preferred taking a well-handed, smart girl, who was known to be well-behaved and industrious, like himself. Here, however, was where the puzzle lay on him; for instead of one girl of that kind, there were in the neighbourhood no less than a dozen of them—all equally fit and willing to become his[20] wife, and all equally good-looking. There were two, however, whom he thought a trifle above the rest; but so nicely balanced were Biddy Corrigan and Sally Gorman, that for the life of him he could not make up his mind to decide between them. Each of them had won her kemp; and it was currently said by them who ought to know, that neither of them could over-match the other. No two girls in the parish were better respected, or deserved to be so; and the consequence was, they had every one's good word and good wish. Now it so happened that Shaun had been pulling a cord with each; and as he knew not how to decide between, he thought he would allow them to do that themselves if they could. He accordingly gave out to the neighbours that he would hold a kemp on that day week, and he told Biddy and Sally especially that he had made up his mind to marry whichever of them won the kemp, for he knew[21] right well, as did all the parish, that one of them must. The girls agreed to this very good-humouredly, Biddy telling Sally that she (Sally) would surely win it; and Sally, not to be outdone in civility, telling the same thing to her.

Well, the week was nearly past, there being but two days till that of the kemp, when, about three o'clock, there walks into the house of old Paddy Corrigan a little woman dressed in high-heeled shoes and a short red cloak. There was no one in the house but Biddy at the time, who rose up and placed a chair near the fire, and asked the little red woman to sit down and rest herself. She accordingly did so, and in a short time a lively chat commenced between them.

'So,' said the strange woman, 'there's to be a great kemp in Shaun Buie M'Gaveran's?'

'Indeed there is that, good woman,' replied Biddy, smiling and blushing to[22] back of that again, because she knew her own fate depended on it.

'And,' continued the little woman, 'whoever wins the kemp wins a husband?'

'Ay, so it seems.'

'Well, whoever gets Shaun will be a happy woman, for he's the moral of a good boy.'

'That's nothing but the truth, anyhow,' replied Biddy, sighing, for fear, you may be sure, that she herself might lose him; and indeed a young woman might sigh from many a worse reason. 'But,' said she, changing the subject, 'you appear to be tired, honest woman, an' I think you had better eat a bit, an' take a good drink of buinnhe ramwher (thick milk) to help you on your journey.'

'Thank you kindly, a colleen,' said the woman; 'I'll take a bit, if you plase, hopin', at the same time, that you won't be the poorer of it this day twelve months.'

'Sure,' said the girl, 'you know[23] that what we give from kindness ever an' always leaves a blessing behind it.'

'Yes, acushla, when it is given from kindness.'

She accordingly helped herself to the food that Biddy placed before her, and appeared, after eating, to be very much refreshed.

'Now,' said she, rising up, 'you're a very good girl, an' if you are able to find out my name before Tuesday morning, the kemp-day, I tell you that you'll win it, and gain the husband.'

'Why,' said Biddy, 'I never saw you before. I don't know who you are, nor where you live; how then can I ever find out your name?'

'You never saw me before, sure enough,' said the old woman, 'an' I tell you that you never will see me again but once; an' yet if you have not my name for me at the close of the kemp, you'll lose all, an' that will leave you a sore heart, for well I know you love Shaun Buie.'[24]

So saying, she went away, and left poor Biddy quite cast down at what she had said, for, to tell the truth, she loved Shaun very much, and had no hopes of being able to find out the name of the little woman, on which, it appeared, so much to her depended.

It was very near the same hour of the same day that Sally Gorman was sitting alone in her father's house, thinking of the kemp, when who should walk in to her but our friend the little red woman.

'God save you, honest woman,' said Sally, 'this is a fine day that's in it, the Lord be praised!'

'It is,' said the woman, 'as fine a day as one could wish for: indeed it is.'

'Have you no news on your travels?' asked Sally.

'The only news in the neighbourhood,' replied the other, 'is this great kemp that's to take place at Shaun Buie M'Gaveran's. They say you're[25] either to win him or lose him then,' she added, looking closely at Sally as she spoke.

'I'm not very much afraid of that,' said Sally, with confidence; 'but even if I do lose him, I may get as good.'

'It's not easy gettin' as good,' rejoined the old woman, 'an' you ought to be very glad to win him, if you can.'

'Let me alone for that,' said Sally. 'Biddy's a good girl, I allow; but as for spinnin', she never saw the day she could leave me behind her. Won't you sit an' rest you?' she added; 'maybe you're tired.'

'It's time for you to think of it,' thought the woman, but she spoke nothing: 'but,' she added to herself on reflection, 'it's better late than never—I'll sit awhile, till I see a little closer what she's made of.'

She accordingly sat down and chatted upon several subjects, such as young women like to talk about, for about[26] half an hour; after which she arose, and taking her little staff in hand, she bade Sally good-bye, and went her way. After passing a little from the house she looked back, and could not help speaking to herself as follows:

Poor Biddy now made all possible inquiries about the old woman, but to no purpose. Not a soul she spoke to about her had ever seen or heard of such a woman. She felt very dispirited, and began to lose heart, for there is no doubt that if she missed Shaun it would have cost her many a sorrowful day. She knew she would never get his equal, or at least any one that she loved so well. At last the kemp day came, and with it all the pretty girls of the neighbourhood to Shaun Buie's. Among the rest, the two that were to[27] decide their right to him were doubtless the handsomest pair by far, and every one admired them. To be sure, it was a blythe and merry place, and many a light laugh and sweet song rang out from pretty lips that day. Biddy and Sally, as every one expected, were far ahead of the rest, but so even in their spinning that the reelers could not for the life of them declare which was the better. It was neck-and-neck and head-and-head between the pretty creatures, and all who were at the kemp felt themselves wound up to the highest pitch of interest and curiosity to know which of them would be successful.

The day was now more than half gone, and no difference was between them, when, to the surprise and sorrow of every one present, Biddy Corrigan's heck broke in two, and so to all appearance ended the contest in favour of her rival; and what added to her mortification, she was as ignorant of[28] the red little woman's name as ever. What was to be done? All that could be done was done. Her brother, a boy of about fourteen years of age, happened to be present when the accident took place, having been sent by his father and mother to bring them word how the match went on between the rival spinsters. Johnny Corrigan was accordingly despatched with all speed to Donnel M'Cusker's, the wheelwright, in order to get the heck mended, that being Biddy's last but hopeless chance. Johnny's anxiety that his sister should win was of course very great, and in order to lose as little time as possible he struck across the country, passing through, or rather close by, Kilrudden forth, a place celebrated as a resort of the fairies. What was his astonishment, however, as he passed a White-thorn tree, to hear a female voice singing, in accompaniment to the sound of a spinning-wheel, the following words:[29]

'There's a girl in this town,' said the lad, 'who's in great distress, for she has broken her heck, and lost a husband. I'm now goin' to Donnel M'Cusker's to get it mended.'

'What's her name?' said the little red woman.

'Biddy Corrigan.'

The little woman immediately whipped out the heck from her own wheel, and giving it to the boy, desired him to take it to his sister, and never mind Donnel M'Cusker.

'You have little time to lose,' she added, 'so go back and give her this; but don't tell her how you got it, nor, above all things, that it was Even Trot that gave it to you.'

The lad returned, and after giving the heck to his sister, as a matter of course told her that it was a little red woman called Even Trot that sent it[30] to her, a circumstance which made tears of delight start to Biddy's eyes, for she knew now that Even Trot was the name of the old woman, and having known that, she felt that something good would happen to her. She now resumed her spinning, and never did human fingers let down the thread so rapidly. The whole kemp were amazed at the quantity which from time to time filled her pirn. The hearts of her friends began to rise, and those of Sally's party to sink, as hour after hour she was fast approaching her rival, who now spun if possible with double speed on finding Biddy coming up with her. At length they were again even, and just at that moment in came her friend the little red woman, and asked aloud, 'Is there any one in this kemp that knows my name?' This question she asked three times before Biddy could pluck up courage to answer her. She at last said,[31]

'Ay,' said the old woman, 'and so it is; and let that name be your guide and your husband's through life. Go steadily along, but let your step be even; stop little; keep always advancing; and you'll never have cause to rue the day that you first saw Even Trot.'

We need scarcely add that Biddy won the kemp and the husband, and that she and Shaun lived long and happily together; and I have only now to wish, kind reader, that you and I may live longer and more happily still.

here lived not long since, on the borders of the county Tipperary, a decent honest couple, whose names were Mick Flannigan and Judy Muldoon. These poor people were blessed, as the saying is, with four children, all boys: three of them were as fine, stout, healthy, good-looking children as ever the sun shone upon; and it was enough to make any Irishman proud of the breed of his countrymen to see them about one o'clock on a fine summer's day standing at their father's cabin[33] door, with their beautiful flaxen hair hanging in curls about their head, and their cheeks like two rosy apples, and a big laughing potato smoking in their hand. A proud man was Mick of these fine children, and a proud woman, too, was Judy; and reason enough they had to be so. But it was far otherwise with the remaining one, which was the third eldest: he was the most miserable, ugly, ill-conditioned brat that ever God put life into; he was so ill-thriven that he never was able to stand alone, or to leave his cradle; he had long, shaggy, matted, curled hair, as black as the soot; his face was of a greenish-yellow colour; his eyes were like two burning coals, and were for ever moving in his head, as if they had the perpetual motion. Before he was a twelvemonth old he had a mouth full of great teeth; his hands were like kites' claws, and his legs were no thicker than the handle of a whip, and about as straight as a reaping-[34]hook: to make the matter worse, he had the appetite of a cormorant, and the whinge, and the yelp, and the screech, and the yowl, was never out of his mouth.

The neighbours all suspected that he was something not right, particularly as it was observed, when people, as they do in the country, got about the fire, and began to talk of religion and good things, the brat, as he lay in the cradle, which his mother generally put near the fireplace that he might be snug, used to sit up, as they were in the middle of their talk, and begin to bellow as if the devil was in him in right earnest; this, as I said, led the neighbours to think that all was not right, and there was a general consultation held one day about what would be best to do with him. Some advised to put him out on the shovel, but Judy's pride was up at that. A pretty thing indeed, that a child of hers should be put on a shovel and flung[35] out on the dunghill just like a dead kitten or a poisoned rat; no, no, she would not hear to that at all. One old woman, who was considered very skilful and knowing in fairy matters, strongly recommended her to put the tongs in the fire, and heat them red hot, and to take his nose in them, and that would beyond all manner of doubt make him tell what he was and where he came from (for the general suspicion was, that he had been changed by the good people); but Judy was too softhearted, and too fond of the imp, so she would not give in to this plan, though everybody said she was wrong, and maybe she was, but it's hard to blame a mother. Well, some advised one thing, and some another; at last one spoke of sending for the priest, who was a very holy and a very learned man, to see it. To this Judy of course had no objection; but one thing or other always prevented her doing so, and the upshot of the[36] business was that the priest never saw him.

Things went on in the old way for some time longer. The brat continued yelping and yowling, and eating more than his three brothers put together, and playing all sorts of unlucky tricks, for he was mighty mischievously inclined, till it happened one day that Tim Carrol, the blind piper, going his rounds, called in and sat down by the fire to have a bit of chat with the woman of the house. So after some time Tim, who was no churl of his music, yoked on the pipes, and began to bellows away in high style; when the instant he began, the young fellow, who had been lying as still as a mouse in his cradle, sat up, began to grin and twist his ugly face, to swing about his long tawny arms, and to kick out his crooked legs, and to show signs of great glee at the music. At last nothing would serve him but he should get the pipes into his own hands, and[37] to humour him his mother asked Tim to lend them to the child for a minute. Tim, who was kind to children, readily consented; and as Tim had not his sight, Judy herself brought them to the cradle, and went to put them on him; but she had no occasion, for the youth seemed quite up to the business. He buckled on the pipes, set the bellows under one arm, and the bag under the other, worked them both as knowingly as if he had been twenty years at the business, and lilted up 'Sheela na guira' in the finest style imaginable.

All were in astonishment: the poor woman crossed herself. Tim, who, as I said before, was dark, and did not well know who was playing, was in great delight; and when he heard that it was a little prechan not five years old, that had never seen a set of pipes in his life, he wished the mother joy of her son; offered to take him off her hands if she would part with him,[38] swore he was a born piper, a natural genus, and declared that in a little time more, with the help of a little good instruction from himself, there would not be his match in the whole country. The poor woman was greatly delighted to hear all this, particularly as what Tim said about natural genus quieted some misgivings that were rising in her mind, lest what the neighbours said about his not being right might be too true; and it gratified her moreover to think that her dear child (for she really loved the whelp) would not be forced to turn out and beg, but might earn decent bread for himself. So when Mick came home in the evening from his work, she up and told him all that had happened, and all that Tim Carrol had said; and Mick, as was natural, was very glad to hear it, for the helpless condition of the poor creature was a great trouble to him. So next day he took the pig to the fair, and with what it brought[39] set off to Clonmel, and bespoke a bran-new set of pipes, of the proper size for him.

In about a fortnight the pipes came home, and the moment the chap in his cradle laid eyes on them he squealed with delight and threw up his pretty legs, and bumped himself in his cradle, and went on with a great many comical tricks; till at last, to quiet him, they gave him the pipes, and he immediately set to and pulled away at 'Jig Polthog,' to the admiration of all who heard him.

The fame of his skill on the pipes soon spread far and near, for there was not a piper in the six next counties could come at all near him, in 'Old Moderagh rue,' or 'The Hare in the Corn,' or 'The Fox-hunter's Jig,' or 'The Rakes of Cashel,' or 'The Piper's Maggot,' or any of the fine Irish jigs which make people dance whether they will or no: and it was surprising to hear him rattle away 'The Fox-hunt'; you'd really think you heard[40] the hounds giving tongue, and the terriers yelping always behind, and the huntsman and the whippers-in cheering or correcting the dogs; it was, in short, the very next thing to seeing the hunt itself.

The best of him was, he was noways stingy of his music, and many a merry dance the boys and girls of the neighbourhood used to have in his father's cabin; and he would play up music for them, that they said used as it were to put quicksilver in their feet; and they all declared they never moved so light and so airy to any piper's playing that ever they danced to.

But besides all his fine Irish music, he had one queer tune of his own, the oddest that ever was heard; for the moment he began to play it everything in the house seemed disposed to dance; the plates and porringers used to jingle on the dresser, the pots and pot-hooks used to rattle in the chimney,[41] and people used even to fancy they felt the stools moving from under them; but, however it might be with the stools, it is certain that no one could keep long sitting on them, for both old and young always fell to capering as hard as ever they could. The girls complained that when he began this tune it always threw them out in their dancing, and that they never could handle their feet rightly, for they felt the floor like ice under them, and themselves every moment ready to come sprawling on their backs or their faces. The young bachelors who wished to show off their dancing and their new pumps, and their bright red or green and yellow garters, swore that it confused them so that they never could go rightly through the heel and toe or cover the buckle, or any of their best steps, but felt themselves always all bedizzied and bewildered, and then old and young would go jostling and knocking to[42]gether in a frightful manner; and when the unlucky brat had them all in this way, whirligigging about the floor, he'd grin and chuckle and chatter, for all the world like Jacko the monkey when he has played off some of his roguery.

The older he grew the worse he grew, and by the time he was six years old there was no standing the house for him; he was always making his brothers burn or scald themselves, or break their shins over the pots and stools. One time, in harvest, he was left at home by himself, and when his mother came in she found the cat a-horseback on the dog, with her face to the tail, and her legs tied round him, and the urchin playing his queer tune to them; so that the dog went barking and jumping about, and puss was mewing for the dear life, and slapping her tail backwards and forwards, which, as it would hit against the dog's chaps, he'd snap at and bite, and then there[43] was the philliloo. Another time, the farmer with whom Mick worked, a very decent, respectable man, happened to call in, and Judy wiped a stool with her apron, and invited him to sit down and rest himself after his walk. He was sitting with his back to the cradle, and behind him was a pan of blood, for Judy was making pig's puddings. The lad lay quite still in his nest, and watched his opportunity till he got ready a hook at the end of a piece of twine, which he contrived to fling so handily that it caught in the bob of the man's nice new wig, and soused it in the pan of blood. Another time his mother was coming in from milking the cow, with the pail on her head: the minute he saw her he lilted up his infernal tune, and the poor woman, letting go the pail, clapped her hands aside, and began to dance a jig, and tumbled the milk all a-top of her husband, who was bringing in some turf to boil the supper. In[44] short, there would be no end to telling all his pranks, and all the mischievous tricks he played.

Soon after, some mischances began to happen to the farmer's cattle. A horse took the staggers, a fine veal calf died of the black-leg, and some of his sheep of the red-water; the cows began to grow vicious, and to kick down the milk-pails, and the roof of one end of the barn fell in; and the farmer took it into his head that Mick Flannigan's unlucky child was the cause of all the mischief. So one day he called Mick aside, and said to him, 'Mick, you see things are not going on with me as they ought, and to be plain with you, Mick, I think that child of yours is the cause of it. I am really falling away to nothing with fretting, and I can hardly sleep on my bed at night for thinking of what may happen before the morning. So I'd be glad if you'd look out for work somewhere else; you're as good a man as any in the[45] country, and there's no fear but you'll have your choice of work.' To this Mick replied, 'that he was sorry for his losses, and still sorrier that he or his should be thought to be the cause of them; that for his own part he was not quite easy in his mind about that child, but he had him and so must keep him'; and he promised to look out for another place immediately.

Accordingly, next Sunday at chapel Mick gave out that he was about leaving the work at John Riordan's, and immediately a farmer who lived a couple of miles off, and who wanted a ploughman (the last one having just left him), came up to Mick, and offered him a house and garden, and work all the year round. Mick, who knew him to be a good employer, immediately closed with him; so it was agreed that the farmer should send a car[2] to take his little bit of furniture, and that [46]he should remove on the following Thursday.

When Thursday came, the car came according to promise, and Mick loaded it, and put the cradle with the child and his pipes on the top, and Judy sat beside it to take care of him, lest he should tumble out and be killed. They drove the cow before them, the dog followed, but the cat was of course left behind; and the other three children went along the road picking skeehories (haws) and blackberries, for it was a fine day towards the latter end of harvest.

They had to cross a river, but as it ran through a bottom between two high banks, you did not see it till you were close on it. The young fellow was lying pretty quiet in the bottom of the cradle, till they came to the head of the bridge, when hearing the roaring of the water (for there was a great flood in the river, as it had rained heavily for the last two or three days),[47] he sat up in his cradle and looked about him; and the instant he got a sight of the water, and found they were going to take him across it, oh, how he did bellow and how he did squeal! no rat caught in a snap-trap ever sang out equal to him. 'Whist! A lanna,' said Judy, 'there's no fear of you; sure it's only over the stone bridge we're going.'—'Bad luck to you, you old rip!' cried he, 'what a pretty trick you've played me to bring me here!' and still went on yelling, and the farther they got on the bridge the louder he yelled; till at last Mick could hold out no longer, so giving him a great skelp of the whip he had in his hand, 'Devil choke you, you brat!' said he, 'will you never stop bawling? a body can't hear their ears for you.' The moment he felt the thong of the whip he leaped up in the cradle, clapped the pipes under his arm, gave a most wicked grin at Mick, and jumped clean over the battlements[48] of the bridge down into the water. 'Oh, my child, my child!' shouted Judy, 'he's gone for ever from me.' Mick and the rest of the children ran to the other side of the bridge, and looking over, they saw him coming out from under the arch of the bridge, sitting cross-legged on the top of a white-headed wave, and playing away on the pipes as merrily as if nothing had happened. The river was running very rapidly, so he was whirled away at a great rate; but he played as fast, ay, and faster, than the river ran; and though they set off as hard as they could along the bank, yet, as the river made a sudden turn round the hill, about a hundred yards below the bridge, by the time they got there he was out of sight, and no one ever laid eyes on him more; but the general opinion was that he went home with the pipes to his own relations, the good people, to make music for them.

[2] Car, a cart.

n the times when we used to travel by canal I was coming down from Dublin. When we came to Mullingar the canal ended, and I began to walk, and stiff and fatigued I was after the slowness. I had some friends with me, and now and then we walked, now and then we rode in a cart. So on till we saw some girls milking a cow, and stopped to joke with them. After a while we asked them for a drink of milk. 'We have nothing to[50] put it in here,' they said, 'but come to the house with us.' We went home with them and sat round the fire talking. After a while the others went, and left me, loath to stir from the good fire. I asked the girls for something to eat. There was a pot on the fire, and they took the meat out and put it on a plate and told me to eat only the meat that came from the head. When I had eaten, the girls went out and I did not see them again.

It grew darker and darker, and there I still sat, loath as ever to leave the good fire; and after a while two men came in, carrying between them a corpse. When I saw them I hid behind the door. Says one to the other, 'Who'll turn the spit?' Says the other, 'Michael Hart, come out of that and turn the meat!' I came out in a tremble and began turning the spit. 'Michael Hart,' says the one who spoke first, 'if you let it burn we will have to put you on the spit[51] instead,' and on that they went out. I sat there trembling and turning the corpse until midnight. The men came again, and the one said it was burnt, and the other said it was done right, but having fallen out over it, they both said they would do me no harm that time; and sitting by the fire one of them cried out, 'Michael Hart, can you tell a story?' 'Never a one,' said I. On that he caught me by the shoulders and put me out like a shot.

It was a wild, blowing night; never in all my born days did I see such a night—the darkest night that ever came out of the heavens. I did not know where I was for the life of me. So when one of the men came after me and touched me on the shoulder with a 'Michael Hart, can you tell a story now?'—'I can,' says I. In he brought me, and, putting me by the fire, says 'Begin.' 'I have no story but the one,' says I, 'that I was sitting here, and that you two men brought[52] in a corpse and put it on the spit and set me turning it.' 'That will do,' says he; 'you may go in there and lie down on the bed.' And in I went, nothing loath, and in the morning where was I but in the middle of a green field.

can't stop in the house—I won't stop in it for all the money that is buried in the old castle of Carrigrohan. If ever there was such a thing in the world!—to be abused to my face night and day, and nobody to the fore doing it! and then, if I'm angry, to be laughed at with a great roaring ho, ho, ho! I won't stay in the house after to-night, if there was not another place in the country to put my head under.' This angry soliloquy was pronounced in the hall[54] of the old manor-house of Carrigrohan by John Sheehan. John was a new servant; he had been only three days in the house, which had the character of being haunted, and in that short space of time he had been abused and laughed at by a voice which sounded as if a man spoke with his head in a cask; nor could he discover who was the speaker, or from whence the voice came. 'I'll not stop here,' said John; 'and that ends the matter.'

'Ho, ho, ho! be quiet, John Sheehan, or else worse will happen to you.'

John instantly ran to the hall window, as the words were evidently spoken by a person immediately outside, but no one was visible. He had scarcely placed his face at the pane of glass when he heard another loud 'Ho, ho, ho!' as if behind him in the hall; as quick as lightning he turned his head, but no living thing was to be seen.[55]

'Ho, ho, ho, John!' shouted a voice that appeared to come from the lawn before the house: 'do you think you'll see Teigue?—oh, never! as long as you live! so leave alone looking after him, and mind your business; there's plenty of company to dinner from Cork to be here to-day, and 'tis time you had the cloth laid.'

'Lord bless us! there's more of it!—I'll never stay another day here,' repeated John.

'Hold your tongue, and stay where you are quietly, and play no tricks on Mr. Pratt, as you did on Mr. Jervois about the spoons.'

John Sheehan was confounded by this address from his invisible persecutor, but nevertheless he mustered courage enough to say, 'Who are you? come here, and let me see you, if you are a man'; but he received in reply only a laugh of unearthly derision, which was followed by a 'Good-bye—I'll watch you at dinner, John!'[56]

'Lord between us and harm! this beats all! I'll watch you at dinner! maybe you will! 'tis the broad daylight, so 'tis no ghost; but this is a terrible place, and this is the last day I'll stay in it. How does he know about the spoons? if he tells it I'm a ruined man! there was no living soul could tell it to him but Tim Barrett, and he's far enough off in the wilds of Botany Bay now, so how could he know it? I can't tell for the world! But what's that I see there at the corner of the wall! 'tis not a man! oh, what a fool I am! 'tis only the old stump of a tree! But this is a shocking place—I'll never stop in it, for I'll leave the house to-morrow; the very look of it is enough to frighten any one.'

The mansion had certainly an air of desolation; it was situated in a lawn, which had nothing to break its uniform level save a few tufts of narcissuses and a couple of old trees coeval with[57] the building. The house stood at a short distance from the road, it was upwards of a century old, and Time was doing his work upon it; its walls were weather-stained in all colours, its roof showed various white patches, it had no look of comfort; all was dim and dingy without, and within there was an air of gloom, of departed and departing greatness, which harmonised well with the exterior. It required all the exuberance of youth and of gaiety to remove the impression, almost amounting to awe, with which you trod the huge square hall, paced along the gallery which surrounded the hall, or explored the long rambling passages below stairs. The ballroom, as the large drawing-room was called, and several other apartments, were in a state of decay; the walls were stained with damp, and I remember well the sensation of awe which I felt creeping over me when, boy as I was, and full of boyish life and wild and ardent[58] spirits, I descended to the vaults; all without and within me became chilled beneath their dampness and gloom—their extent, too, terrified me; nor could the merriment of my two schoolfellows, whose father, a respectable clergyman, rented the dwelling for a time, dispel the feelings of a romantic imagination until I once again ascended to the upper regions.

John had pretty well recovered himself as the dinner-hour approached, and several guests arrived. They were all seated at the table, and had begun to enjoy the excellent repast, when a voice was heard in the lawn.

'Ho, ho, ho! Mr. Pratt, won't you give poor Teigue some dinner? ho, ho! a fine company you have there, and plenty of everything that's good; sure you won't forget poor Teigue?'

John dropped the glass he had in his hand.

'Who is that?' said Mr. Pratt's brother, an officer of the artillery.[59]

'That is Teigue,' said Mr. Pratt, laughing, 'whom you must often have heard me mention.'

'And pray, Mr. Pratt,' inquired another gentleman, 'who is Teigue?'

'That,' he replied, 'is more than I can tell. No one has ever been able to catch even a glimpse of him. I have been on the watch for a whole evening with three of my sons, yet, although his voice sometimes sounded almost in my ear, I could not see him. I fancied, indeed, that I saw a man in a white frieze jacket pass into the door from the garden to the lawn, but it could be only fancy, for I found the door locked, while the fellow, whoever he is, was laughing at our trouble. He visits us occasionally, and sometimes a long interval passes between his visits, as in the present case; it is now nearly two years since we heard that hollow voice outside the window. He has never done any injury that we know of, and once when he broke a[60] plate, he brought one back exactly like it.'

'It is very extraordinary,' exclaimed several of the company.

'But,' remarked a gentleman to young Mr. Pratt, 'your father said he broke a plate; how did he get it without your seeing him?'

'When he asks for some dinner we put it outside the window and go away; whilst we watch he will not take it, but no sooner have we withdrawn than it is gone.'

'How does he know that you are watching?'

'That's more than I can tell, but he either knows or suspects. One day my brothers Robert and James with myself were in our back parlour, which has a window into the garden, when he came outside and said, "Ho, ho, ho! Master James and Robert and Henry, give poor Teigue a glass of whisky." James went out of the room, filled a glass with whisky, vinegar, and[61] salt, and brought it to him. "Here, Teigue," said he, "come for it now."—"Well, put it down, then, on the step outside the window." This was done, and we stood looking at it. "There, now, go away," he shouted. We retired, but still watched it. "Ho, ho! you are watching Teigue! go out of the room, now, or I won't take it." We went outside the door and returned, the glass was gone, and a moment after we heard him roaring and cursing frightfully. He took away the glass, but the next day it was on the stone step under the window, and there were crumbs of bread in the inside, as if he had put it in his pocket; from that time he has not been heard till to-day.'

'Oh,' said the colonel, 'I'll get a sight of him; you are not used to these things; an old soldier has the best chance, and as I shall finish my dinner with this wing, I'll be ready for him when he speaks next—Mr. Bell, will you take a glass of wine with me?'[62]

'Ho, ho! Mr. Bell,' shouted Teigue. 'Ho, ho! Mr. Bell, you were a Quaker long ago. Ho, ho! Mr. Bell, you're a pretty boy! a pretty Quaker you were; and now you're no Quaker, nor anything else: ho, ho! Mr. Bell. And there's Mr. Parkes: to be sure, Mr. Parkes looks mighty fine to-day, with his powdered head, and his grand silk stockings and his bran-new rakish-red waistcoat. And there's Mr. Cole: did you ever see such a fellow? A pretty company you've brought together, Mr. Pratt: kiln-dried Quakers, butter-buying buckeens from Mallow Lane, and a drinking exciseman from the Coal Quay, to meet the great thundering artillery general that is come out of the Indies, and is the biggest dust of them all.'

'You scoundrel!' exclaimed the colonel, 'I'll make you show yourself'; and snatching up his sword from a corner of the room, he sprang out of the window upon the lawn. In a moment a shout of laughter, so hollow,[63] so unlike any human sound, made him stop, as well as Mr. Bell, who with a huge oak stick was close at the colonel's heels; others of the party followed to the lawn, and the remainder rose and went to the windows. 'Come on, colonel,' said Mr. Bell; 'let us catch this impudent rascal.'

'Ho, ho! Mr. Bell, here I am—here's Teigue—why don't you catch him? Ho, ho! Colonel Pratt, what a pretty soldier you are to draw your sword upon poor Teigue, that never did anybody harm.'

'Let us see your face, you scoundrel,' said the colonel.

'Ho, ho, ho!—look at me—look at me: do you see the wind, Colonel Pratt? you'll see Teigue as soon; so go in and finish your dinner.'

'If you're upon the earth, I'll find you, you villain!' said the colonel, whilst the same unearthly shout of derision seemed to come from behind an angle of the building. 'He's[64] round that corner,' said Mr. Bell, 'run, run.'

They followed the sound, which was continued at intervals along the garden wall, but could discover no human being; at last both stopped to draw breath, and in an instant, almost at their ears, sounded the shout—

'Ho, ho, ho! Colonel Pratt, do you see Teigue now? do you hear him? Ho, ho, ho! you're a fine colonel to follow the wind.'

'Not that way, Mr. Bell—not that way; come here,' said the colonel.

'Ho, ho, ho! what a fool you are; do you think Teigue is going to show himself to you in the field, there? But, colonel, follow me if you can: you a soldier! ho, ho, ho!' The colonel was enraged: he followed the voice over hedge and ditch, alternately laughed at and taunted by the unseen object of his pursuit (Mr. Bell, who was heavy, was soon thrown out); until at length, after being led a weary[65] chase, he found himself at the top of the cliff, over that part of the river Lee, which, from its great depth, and the blackness of its water, has received the name of Hell-hole. Here, on the edge of the cliff, stood the colonel out of breath, and mopping his forehead with his handkerchief, while the voice, which seemed close at his feet, exclaimed, 'Now, Colonel Pratt, now, if you're a soldier, here's a leap for you! Now look at Teigue—why don't you look at him? Ho, ho, ho! Come along; you're warm, I'm sure, Colonel Pratt, so come in and cool yourself; Teigue is going to have a swim!' The voice seemed as if descending amongst the trailing ivy and brushwood which clothes this picturesque cliff nearly from top to bottom, yet it was impossible that any human being could have found footing. 'Now, colonel, have you courage to take the leap? Ho, ho, ho! what a pretty soldier you are. Good-bye; I'll see you again in ten[66] minutes above, at the house—look at your watch, colonel: there's a dive for you'; and a heavy plunge into the water was heard. The colonel stood still, but no sound followed, and he walked slowly back to the house, not quite half a mile from the Crag.

'Well, did you see Teigue?' said his brother, whilst his nephews, scarcely able to smother their laughter, stood by.

'Give me some wine,' said the colonel. 'I never was led such a dance in my life; the fellow carried me all round and round till he brought me to the edge of the cliff, and then down he went into Hell-hole, telling me he'd be here in ten minutes; 'tis more than that now, but he's not come.'

'Ho, ho, ho! colonel, isn't he here? Teigue never told a lie in his life: but, Mr. Pratt, give me a drink and my dinner, and then good-night to you all,[67] for I'm tired; and that's the colonel's doing.' A plate of food was ordered; it was placed by John, with fear and trembling, on the lawn under the window. Every one kept on the watch, and the plate remained undisturbed for some time.

'Ah! Mr. Pratt, will you starve poor Teigue? Make every one go away from the windows, and Master Henry out of the tree, and Master Richard off the garden wall.'

The eyes of the company were turned to the tree and the garden wall; the two boys' attention was occupied in getting down; the visitors were looking at them; and 'Ho, ho, ho!—good luck to you, Mr. Pratt! 'tis a good dinner, and there's the plate, ladies and gentlemen. Good-bye to you, colonel!—good-bye, Mr. Bell! good-bye to you all!' brought their attention back, when they saw the empty plate lying on the grass; and Teigue's voice was heard no more[68] for that evening. Many visits were afterwards paid by Teigue; but never was he seen, nor was any discovery ever made of his person or character.

addy M'Dermid was one of the most rollicking boys in the whole county of Kildare. Fair or pattern[3] wouldn't be held barring he was in the midst of it. He was in every place, like bad luck, and his poor little farm was seldom sowed in season; and where he expected barley, there grew nothing but weeds. Money became scarce in poor Paddy's pocket; and the cow went after the pig, until nearly [70]all he had was gone. Lucky however for him, if he had gomch (sense) enough to mind it, he had a most beautiful dream one night as he lay tossicated (drunk) in the Rath[4] of Monogue, because he wasn't able to come home. He dreamt that, under the place where he lay, a pot of money was buried since long before the memory of man. Paddy kept the dream to himself until the next night, when, taking a spade and pickaxe, with a bottle of holy water, he went to the Rath, and, having made a circle round the place, commenced diggin' sure enough, for the bare life and sowl of him thinkin' that he was made up for ever and ever. He had sunk about twice the depth of his knees, when whack the pickaxe struck against a flag, and at the same time Paddy heard something breathe quite near him. He looked up, and just [71]fornent him there sat on his haunches a comely-looking greyhound.

"FORNENT HIM THERE SAT ON HIS HAUNCHES A COMELY-LOOKING

GREYHOUND."

"FORNENT HIM THERE SAT ON HIS HAUNCHES A COMELY-LOOKING

GREYHOUND."

'God save you,' said Paddy, every hair in his head standing up as straight as a sally twig.

'Save you kindly,' answered the greyhound—leaving out God, the beast, bekase he was the divil. Christ defend us from ever seeing the likes o' him.

'Musha, Paddy M'Dermid,' said he, 'what would you be looking after in that grave of a hole you're diggin' there?'

'Faith, nothing at all, at all,' answered Paddy; bekase you see he didn't like the stranger.

'Arrah, be easy now, Paddy M'Dermid,' said the greyhound; 'don't I know very well what you are looking for?'

'Why then in truth, if you do, I may as well tell you at wonst, particularly as you seem a civil-looking gentleman, that's not above speak[72]ing to a poor gossoon like myself.' (Paddy wanted to butter him up a bit.)

'Well then,' said the greyhound, 'come out here and sit down on this bank,' and Paddy, like a gomulagh (fool), did as he was desired, but had hardly put his brogue outside of the circle made by the holy water, when the beast of a hound set upon him, and drove him out of the Rath; for Paddy was frightened, as well he might, at the fire that flamed from his mouth. But next night he returned, full sure the money was there. As before, he made a circle, and touched the flag, when my gentleman, the greyhound, appeared in the ould place.

'Oh ho,' said Paddy, 'you are there, are you? but it will be a long day, I promise you, before you trick me again'; and he made another stroke at the flag.

'Well, Paddy M'Dermid,' said the[73] hound, 'since you will have money, you must; but say, how much will satisfy you?'

Paddy scratched his conlaan, and after a while said—

'How much will your honour give me?' for he thought it better to be civil.

'Just as much as you consider reasonable, Paddy M'Dermid.'

'Egad,' says Paddy to himself, 'there's nothing like axin' enough.'

'Say fifty thousand pounds,' said he. (He might as well have said a hundred thousand, for I'll be bail the beast had money gulloure.)

'You shall have it,' said the hound; and then, after trotting away a little bit, he came back with a crock full of guineas between his paws.

'Come here and reckon them,' said he; but Paddy was up to him, and refused to stir, so the crock was shoved alongside the blessed and holy circle, and Paddy pulled it in, right glad to[74] have it in his clutches, and never stood still until he reached his own home, where his guineas turned into little bones, and his ould mother laughed at him. Paddy now swore vengeance against the deceitful beast of a greyhound, and went next night to the Rath again, where, as before, he met Mr. Hound.

'So you are here again, Paddy?' said he.

'Yes, you big blaggard,' said Paddy, 'and I'll never leave this place until I pull out the pot of money that's buried here.'

'Oh, you won't,' said he. 'Well, Paddy M'Dermid, since I see you are such a brave venturesome fellow I'll be after making you up if you walk downstairs with me out of the could'; and sure enough it was snowing like murder.

'Oh may I never see Athy if I do,' returned Paddy, 'for you only want to be loading me with ould bones,[75] or perhaps breaking my own, which would be just as bad.'

''Pon honour,' said the hound, 'I am your friend; and so don't stand in your own light; come with me and your fortune is made. Remain where you are and you'll die a beggar-man.' So bedad, with one palaver and another, Paddy consented; and in the middle of the Rath opened up a beautiful staircase, down which they walked; and after winding and turning they came to a house much finer than the Duke of Leinster's, in which all the tables and chairs were solid gold. Paddy was delighted; and after sitting down, a fine lady handed him a glass of something to drink; but he had hardly swallowed a spoonful when all around set up a horrid yell, and those who before appeared beautiful now looked like what they were—enraged 'good people' (fairies). Before Paddy could bless himself, they seized him, legs and arms, carried him out to a[76] great high hill that stood like a wall over a river, and flung him down. 'Murder!' cried Paddy; but it was no use, no use; he fell upon a rock, and lay there as dead until next morning, where some people found him in the trench that surrounds the mote of Coulhall, the 'good people' having carried him there; and from that hour to the day of his death he was the greatest object in the world. He walked double, and had his mouth (God bless us) where his ear should be.

[3] A merry-making in the honour of some patron saint.

[4] Raths are little fields enclosed by circular ditches. They are thought to be the sheep-folds and dwellings of an ancient people.

n the shore of Smerwick harbour, one fine summer's morning, just at daybreak, stood Dick Fitzgerald 'shoghing the dudeen,' which may be translated, smoking his pipe. The sun was gradually rising behind the lofty Brandon, the dark sea was getting green in the light, and the mists clearing away out of the valleys went rolling and curling like the smoke from the corner of Dick's mouth.

''Tis just the pattern of a pretty morning,' said Dick, taking the pipe[78] from between his lips, and looking towards the distant ocean, which lay as still and tranquil as a tomb of polished marble. 'Well, to be sure,' continued he, after a pause, ''tis mighty lonesome to be talking to one's self by way of company, and not to have another soul to answer one—nothing but the child of one's own voice, the echo! I know this, that if I had the luck, or may be the misfortune,' said Dick, with a melancholy smile, 'to have the woman, it would not be this way with me! and what in the wide world is a man without a wife? He's no more surely than a bottle without a drop of drink in it, or dancing without music, or the left leg of a scissors, or a fishing-line without a hook, or any other matter that is no ways complete. Is it not so?' said Dick Fitzgerald, casting his eyes towards a rock upon the strand, which, though it could not speak, stood up as firm and looked as bold as ever Kerry witness did.[79]

But what was his astonishment at beholding, just at the foot of that rock, a beautiful young creature combing her hair, which was of a sea-green colour; and now the salt water shining on it appeared, in the morning light, like melted butter upon cabbage.

Dick guessed at once that she was a Merrow,[5] although he had never seen one before, for he spied the cohuleen driuth, or little enchanted cap, which the sea people use for diving down into the ocean, lying upon the strand near her; and he had heard that, if once he could possess himself of the cap she would lose the power of going away into the water: so he seized it with all speed, and she, hearing the noise, turned her head about as natural as any Christian.

When the Merrow saw that her little diving-cap was gone, the salt tears—doubly salt, no doubt, from her—came trickling down her cheeks, and [80]she began a low mournful cry with just the tender voice of a new-born infant. Dick, although he knew well enough what she was crying for, determined to keep the cohuleen driuth, let her cry never so much, to see what luck would come out of it. Yet he could not help pitying her; and when the dumb thing looked up in his face, with her cheeks all moist with tears, 'twas enough to make any one feel, let alone Dick, who had ever and always, like most of his countrymen, a mighty tender heart of his own.

'Don't cry, my darling,' said Dick Fitzgerald; but the Merrow, like any bold child, only cried the more for that.

Dick sat himself down by her side, and took hold of her hand by way of comforting her. 'Twas in no particular an ugly hand, only there was a small web between the fingers, as there is in a duck's foot; but 'twas as thin and as white as the skin between egg and shell.[81]

'What's your name, my darling?' says Dick, thinking to make her conversant with him; but he got no answer; and he was certain sure now, either that she could not speak, or did not understand him: he therefore squeezed her hand in his, as the only way he had of talking to her. It's the universal language; and there's not a woman in the world, be she fish or lady, that does not understand it.

The Merrow did not seem much displeased at this mode of conversation; and making an end of her whining all at once, 'Man,' says she, looking up in Dick Fitzgerald's face; 'man, will you eat me?'

'By all the red petticoats and check aprons between Dingle and Tralee,' cried Dick, jumping up in amazement, 'I'd as soon eat myself, my jewel! Is it I eat you, my pet? Now, 'twas some ugly ill-looking thief of a fish put that notion into your own pretty head, with the nice green hair down upon it,[82] that is so cleanly combed out this morning!'

'Man,' said the Merrow, 'what will you do with me if you won't eat me?'

Dick's thoughts were running on a wife: he saw, at the first glimpse, that she was handsome; but since she spoke, and spoke too like any real woman, he was fairly in love with her. 'Twas the neat way she called him man that settled the matter entirely.

'Fish,' says Dick, trying to speak to her after her own short fashion; 'fish,' says he, 'here's my word, fresh and fasting, for you this blessed morning, that I'll make you Mistress Fitzgerald before all the world, and that's what I'll do.'

'Never say the word twice,' says she; 'I'm ready and willing to be yours, Mister Fitzgerald; but stop, if you please, till I twist up my hair.' It was some time before she had settled it entirely to her liking; for she guessed, I suppose, that she was going among[83] strangers, where she would be looked at. When that was done, the Merrow put the comb in her pocket, and then bent down her head and whispered some words to the water that was close to the foot of the rock.

Dick saw the murmur of the words upon the top of the sea, going out towards the wide ocean, just like a breath of wind rippling along, and, says he, in the greatest wonder, 'Is it speaking you are, my darling, to the salt water?'

'It's nothing else,' says she, quite carelessly; 'I'm just sending word home to my father not to be waiting breakfast for me; just to keep him from being uneasy in his mind.'

'And who's your father, my duck?' said Dick.

'What!' said the Merrow, 'did you never hear of my father? he's the king of the waves to be sure!'

'And yourself, then, is a real king's daughter?' said Dick, opening his two[84] eyes to take a full and true survey of his wife that was to be. 'Oh, I'm nothing else but a made man with you, and a king your father; to be sure he has all the money that's down at the bottom of the sea!'

'Money,' repeated the Merrow, 'what's money?'

''Tis no bad thing to have when one wants it,' replied Dick; 'and may be now the fishes have the understanding to bring up whatever you bid them?'

'Oh yes,' said the Merrow, 'they bring me what I want.'

'To speak the truth then,' said Dick, ''tis a straw bed I have at home before you, and that, I'm thinking, is no ways fitting for a king's daughter; so if 'twould not be displeasing to you, just to mention a nice feather bed, with a pair of new blankets—but what am I talking about? may be you have not such things as beds down under the water?'

'By all means,' said she, 'Mr.[85] Fitzgerald—plenty of beds at your service. I've fourteen oyster-beds of my own, not to mention one just planting for the rearing of young ones.'

'You have?' says Dick, scratching his head and looking a little puzzled. ''Tis a feather bed I was speaking of; but, clearly, yours is the very cut of a decent plan to have bed and supper so handy to each other, that a person when they'd have the one need never ask for the other.'

However, bed or no bed, money or no money, Dick Fitzgerald determined to marry the Merrow, and the Merrow had given her consent. Away they went, therefore, across the strand, from Gollerus to Ballinrunnig, where Father Fitzgibbon happened to be that morning.

'There are two words to this bargain, Dick Fitzgerald,' said his Reverence, looking mighty glum. 'And is it a fishy woman you'd marry? The Lord preserve us! Send the scaly creature[86] home to her own people; that's my advice to you, wherever she came from.'

Dick had the cohuleen driuth in his hand, and was about to give it back to the Merrow, who looked covetously at it, but he thought for a moment, and then says he, 'Please your Reverence, she's a king's daughter.'

'If she was the daughter of fifty kings,' said Father Fitzgibbon, 'I tell you, you can't marry her, she being a fish.'

'Please your Reverence,' said Dick again, in an undertone, 'she is as mild and as beautiful as the moon.'

'If she was as mild and as beautiful as the sun, moon, and stars, all put together, I tell you, Dick Fitzgerald,' said the Priest, stamping his right foot, 'you can't marry her, she being a fish.'

'But she has all the gold that's down in the sea only for the asking, and I'm a made man if I marry her; and,' said Dick, looking up slily, 'I can[87] make it worth any one's while to do the job.'

'Oh! that alters the case entirely,' replied the Priest; 'why there's some reason now in what you say: why didn't you tell me this before? marry her by all means, if she was ten times a fish. Money, you know, is not to be refused in these bad times, and I may as well have the hansel of it as another, that may be would not take half the pains in counselling you that I have done.'

So Father Fitzgibbon married Dick Fitzgerald to the Merrow, and like any loving couple, they returned to Gollerus well pleased with each other. Everything prospered with Dick—he was at the sunny side of the world; the Merrow made the best of wives, and they lived together in the greatest contentment.

It was wonderful to see, considering where she had been brought up, how she would busy herself about the house,[88] and how well she nursed the children; for, at the end of three years there were as many young Fitzgeralds—two boys and a girl.

In short, Dick was a happy man, and so he might have been to the end of his days if he had only had the sense to take care of what he had got; many another man, however, beside Dick, has not had wit enough to do that.

One day, when Dick was obliged to go to Tralee, he left the wife minding the children at home after him, and thinking she had plenty to do without disturbing his fishing-tackle.

Dick was no sooner gone than Mrs. Fitzgerald set about cleaning up the house, and chancing to pull down a fishing-net, what should she find behind it in a hole in the wall but her own cohuleen driuth. She took it out and looked at it, and then she thought of her father the king, and her mother the queen, and her brothers and sisters,[89] and she felt a longing to go back to them.

She sat down on a little stool and thought over the happy days she had spent under the sea; then she looked at her children, and thought on the love and affection of poor Dick, and how it would break his heart to lose her. 'But,' says she, 'he won't lose me entirely, for I'll come back to him again, and who can blame me for going to see my father and my mother after being so long away from them?'

She got up and went towards the door, but came back again to look once more at the child that was sleeping in the cradle. She kissed it gently, and as she kissed it a tear trembled for an instant in her eye and then fell on its rosy cheek. She wiped away the tear, and turning to the eldest little girl, told her to take good care of her brothers, and to be a good child herself until she came back. The Merrow then went down to the strand. The[90] sea was lying calm and smooth, just heaving and glittering in the sun, and she thought she heard a faint sweet singing, inviting her to come down. All her old ideas and feelings came flooding over her mind, Dick and her children were at the instant forgotten, and placing the cohuleen driuth on her head she plunged in.

Dick came home in the evening, and missing his wife he asked Kathleen, his little girl, what had become of her mother, but she could not tell him. He then inquired of the neighbours, and he learned that she was seen going towards the strand with a strange-looking thing like a cocked hat in her hand. He returned to his cabin to search for the cohuleen driuth. It was gone, and the truth now flashed upon him.

Year after year did Dick Fitzgerald wait expecting the return of his wife, but he never saw her more. Dick never married again, always thinking[91] that the Merrow would sooner or later return to him, and nothing could ever persuade him but that her father the king kept her below by main force; 'for,' said Dick, 'she surely would not of herself give up her husband and her children.'

While she was with him she was so good a wife in every respect that to this day she is spoken of in the tradition of the country as the pattern for one, under the name of The Lady of Gollerus.

[5] Sea fairy.

ou see, sir, there was a colonel wanst, in times back, that owned a power of land about here—but God keep uz, they said he didn't come by it honestly, but did a crooked turn whenever 'twas to sarve himself.

Well, the story goes that at last the divil (God bless us) kem to him, and promised him hapes o' money, and all his heart could desire and more, too, if he'd sell his sowl in exchange.

He was too cunnin' for that; bad as he was—and he was bad enough[96] God knows—he had some regard for his poor sinful sowl, and he would not give himself up to the divil, all out; but, the villain, he thought he might make a bargain with the old chap, and get all he wanted, and keep himself out of harm's way still: for he was mighty 'cute—and, throth, he was able for Owld Nick any day.

Well, the bargain was struck, and it was this-a-way: the divil was to give him all the goold ever he'd ask for, and was to let him alone as long as he could; and the timpter promised him a long day, and said 'twould be a great while before he'd want him at all, at all; and whin that time kem, he was to keep his hands aff him, as long as the other could give him some work he couldn't do.

So, when the bargain was made, 'Now,' says the colonel to the divil, 'give me all the money I want.'

'As much as you like,' says Owld Nick; 'how much will you have?'[97]

'You must fill me that room,' says he, pointin' into a murtherin' big room that he emptied out on purpose—'you must fill that room,' says he, 'up to the very ceilin' with goolden guineas.'

'And welkem,' says the divil.

With that, sir, he began to shovel the guineas into the room like mad; and the colonel towld him, that as soon as he was done, to come to him in his own parlour below, and that he would then go up and see if the divil was as good as his word, and had filled the room with the goolden guineas. So the colonel went downstairs, and the owld fellow worked away as busy as a nailer, shovellin' in the guineas by hundherds and thousands.

Well, he worked away for an hour and more, and at last he began to get tired; and he thought it mighty odd that the room wasn't fillin' fasther. Well, afther restin' for awhile, he began agin, and he put his shouldher to the[98] work in airnest; but still the room was no fuller at all, at all.

'Och! bad luck to me,' says the divil, 'but the likes of this I never seen,' says he, 'far and near, up and down—the dickens a room I ever kem across afore,' says he, 'I couldn't cram while a cook would be crammin' a turkey, till now; and here I am,' says he, 'losin' my whole day, and I with such a power o' work an my hands yit, and this room no fuller than five minutes ago.'

Begor, while he was spakin' he seen the hape o' guineas in the middle of the flure growing littler and littler every minit; and at last they wor disappearing, for all the world like corn in the hopper of a mill.

'Ho! ho!' says Owld Nick, 'is that the way wid you?' says he; and wid that, he ran over to the hape of goold—and what would you think, but it was runnin' down through a great big hole in the flure, that the colonel made[99] through the ceilin' in the room below; and that was the work he was at afther he left the divil, though he purtended he was only waitin' for him in his parlour; and there the divil, when he looked down the hole in the flure, seen the colonel, not content with the two rooms full of guineas, but with a big shovel throwin' them into a closet a' one side of him as fast as they fell down. So, putting his head through the hole, he called down to the colonel:

'Hillo, neighbour!' says he.

The colonel looked up, and grew as white as a sheet, when he seen he was found out, and the red eyes starin' down at him through the hole.

'Musha, bad luck to your impudence!' says Owld Nick: 'it is sthrivin' to chate me you are,' says he, 'you villain!'

'Oh, forgive me for this wanst!' says the colonel, 'and, upon the honour of a gintleman,' says he, 'I'll never——'[100]

'Whisht! whisht! you thievin' rogue,' says the divil, 'I'm not angry with you at all, at all, but only like you the betther, bekase you're so cute;—lave off slaving yourself there,' says he, 'you have got goold enough for this time; and whenever you want more, you have only to say the word, and it shall be yours to command.'

So with that, the divil and he parted for that time: and myself doesn't know whether they used to meet often afther or not; but the colonel never wanted money, anyhow, but went on prosperous in the world—and, as the saying is, if he took the dirt out o' the road, it id turn to money wid him; and so, in course of time, he bought great estates, and was a great man entirely—not a greater in Ireland, throth.

At last, afther many years of prosperity, the owld colonel got stricken in years, and he began to have misgivings in his conscience for his[101] wicked doings, and his heart was heavy as the fear of death came upon him; and sure enough, while he had such murnful thoughts, the divil kem to him, and towld him he should go wid him.

Well, to be sure, the owld man was frekened, but he plucked up his courage and his cuteness, and towld the divil, in a bantherin' way, jokin' like, that he had partic'lar business thin, that he was goin' to a party, and hoped an owld friend wouldn't inconvaynience him that-a-way.

The divil said he'd call the next day, and that he must be ready; and sure enough in the evenin' he kem to him; and when the colonel seen him, he reminded him of his bargain that as long as he could give him some work he couldn't do, he wasn't obleeged to go.

'That's thrue,' says the divil.

'I'm glad you're as good as your word, anyhow,' says the colonel.[102]

'I never bruk my word yit,' says the owld chap, cocking up his horns consaitedly; 'honour bright,' says he.

'Well then,' says the colonel, 'build me a mill, down there, by the river,' says he, 'and let me have it finished by to-morrow mornin'.'

'Your will is my pleasure,' says the owld chap, and away he wint; and the colonel thought he had nicked Owld Nick at last, and wint to bed quite aisy in his mind.

But, jewel machree, sure the first thing he heerd the next mornin' was that the whole counthry round was runnin' to see a fine bran new mill that was an the river-side, where the evening before not a thing at all, at all, but rushes was standin', and all, of coorse, wonderin' what brought it there; and some sayin' 'twas not lucky, and many more throubled in their mind, but one and all agreein' it was no good; and that's the very mill forninst you.[103]

But when the colonel heered it he was more throubled than any, of coorse, and began to conthrive what else he could think iv to keep himself out iv the claws of the owld one. Well, he often heerd tell that there was one thing the divil never could do, and I darsay you heerd it too, sir,—that is, that he couldn't make a rope out of the sands of the say; and so when the owld one kem to him the next day and said his job was done, and that now the mill was built he must either tell him somethin' else he wanted done, or come away wid him.

So the colonel said he saw it was all over wid him. 'But,' says he, 'I wouldn't like to go wid you alive, and sure it's all the same to you, alive or dead?'

'Oh, that won't do,' says his frind; 'I can't wait no more,' says he.

'I don't want you to wait, my dear frind,' says the colonel; 'all I want[104] is, that you'll be plased to kill me before you take me away.'

'With pleasure,' says Owld Nick.

'But will you promise me my choice of dyin' one partic'lar way?' says the colonel.

'Half a dozen ways, if it plazes you,' says he.

'You're mighty obleegin',' says the colonel; 'and so,' says he, 'I'd rather die by bein' hanged with a rope made out of the sands of the say,' says he, lookin' mighty knowin' at the owld fellow.

'I've always one about me,' says the divil, 'to obleege my frinds,' says he; and with that he pulls out a rope made of sand, sure enough.

'Oh, it's game you're makin',' says the colonel, growin' as white as a sheet.

'The game is mine, sure enough,' says the owld fellow, grinnin', with a terrible laugh.

'That's not a sand-rope at all,' says the colonel.[105]