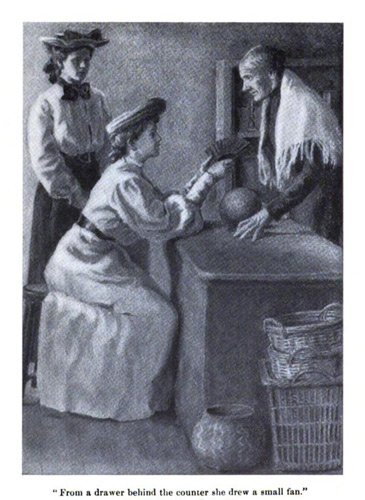

Frontispiece. See p. 25.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Amy in Acadia, by Helen Leah Reed

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Amy in Acadia

A Story for Girls

Author: Helen Leah Reed

Illustrator: Katharine Pyle

Release Date: April 28, 2011 [EBook #35985]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMY IN ACADIA ***

Produced by Heather Clark, Sharon Joiner, Carol Ann Brown,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned

images of public domain material from the Google Print

project.)

Author of "The Brenda Books" "Miss Theodora"

"Irma and Nap"

With Illustrations by Katharine Pyle

Boston

Little, Brown, and Company

1905

Copyright, 1905,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Published October, 1905

The University Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

TO CONSTANCE

my niece,

who journeyed with me through acadia

| Chapter | Page | |

| I | Banished | 1 |

| II | Lost and Found | 14 |

| III | Toward Meteghan | 29 |

| IV | Yvonne | 43 |

| V | New People | 57 |

| VI | Pierre and Point à l'Église | 71 |

| VII | Digby Days | 89 |

| VIII | Two Adventures | 105 |

| IX | Old Port Royal | 119 |

| X | Explorations | 134 |

| XI | A Tea Party | 147 |

| XII | In the Fog | 163 |

| XIII | Letters and Some Comments | 178 |

| XIV | An Excursion | 191 |

| XV | With Prejudice | 204 |

| XVI | Evangeline's Country | 219 |

| XVII | Safe Again | 236 |

| XVIII | The Right and the Wrong of It | 249 |

| XIX | A Discovery | 263 |

| XX | Fire and Flame | 279 |

| XXI | Old Chebucto | 299 |

| XXII | Finding Cousins | 315 |

| XXIII | Good-bye to Halifax | 329 |

| "From a drawer behind the counter she drew a small fan" | Frontispiece |

| "'Madame Bourque,' she cried, 'I asked him to come to see me'" | Page 71 |

| "'Hello! hello!' she shouted" | " 170 |

| "'Why, what is the matter, child?' she asked affectionately" | " 246 |

| "After one ineffectual effort to pry open the lock, the other one had thrown down the scissors" | " 282 |

| "Behind Lucian stalked Malachai, flourishing his cane after the fashion of a drum-major" | " 320 |

banished

"No, Fritz, I cannot—"

"You will not."

"Well, then I will not ask mother to invite you to go on with us."

Amy spoke decidedly, but Fritz was not ready to give up.

"Oh, Amy, do be reasonable! I cannot say anything more to your mother, for you are in an obstinate mood, evidently determined to persuade yourself that you do not wish us to travel with you."

"That is true; I do not wish you to go on with us."

"But you and I are such friends."

"So we are, and so we shall continue to be. Because we are such friends, I am sure that you will forgive me for being so—"

"So unreasonable."

"No—reasonable. Now just look at the whole thing sensibly. Here we are—mamma and I and two girls."

"What do you call yourself? Aren't you a girl?"

"Don't interrupt; perhaps I should have said two schoolgirls. We have come away partly for rest and change, partly for study. So it would only upset all our plans to have you and your friend with us. You'd be dreadfully in the way."

"In the way! I like that. Why, you could rest, or study all day, for all we'd care, and we'd afford you the change that you would certainly need once in a while. Only—if you'll excuse my saying so—who ever heard of any one's resting or studying on a pleasure-trip? Just look at the funny side of it yourself, Amy—and smile—please."

Whereupon, quite against her will, the smile that twitched Amy's lips extended itself into a laugh, in which Fritz Tomkins joined heartily.

"Ah, Amy, that laugh makes me think of old times. So now perhaps you'll condescend to explain why two lonely youths may not visit the historic Acadia in company with you and your mother, not to mention the other members of your party."

Amy made no answer, and Fritz continued:

"Just think what we shall lose! It always benefits me to be with your mother, and you are so full of information, Amy, and you so love to impart what you know, that by the end of the journey I should be a walking guidebook. To go with you would be better than attending a summer school."

"There, Fritz," interrupted Amy, with rising color, "you are getting back at me for what I have said. But we really mean to make this an improving trip."

"So I should judge. Improving only to yourselves."

"Well, then I'll explain, since you find it so hard to understand. You surely know that mamma has been overworking, and yet she does not wish to waste the whole summer. So, after resting a little, she expects to find good sketching-material in Nova Scotia. Then I need more strength before the beginning of my Senior year."

"I'll be a Senior, too, in the autumn," murmured Fritz; but Amy, not heeding the interruption, continued:

"Then there's Priscilla; she has been rather low-spirited since her father died. She is generally in Plymouth in the summer, and this will be a change. Besides, she is to read a little English with me for her Radcliffe examinations."

"Rest—and change—and study, for three of you. Well, I do hope that the other girl is to get some pleasure out of the trip. Didn't you tell me that she comes from Chicago?"

"Oh, Martine finds amusement in everything—even in study. She was at a boarding-school last year on the Hudson, and she made life there so entertaining for herself and her classmates that she had to leave. Her parents then decided to have her visit relatives in Boston this spring. Next year she's to go to Miss Crawdon's. She's especially in mother's care, and I do hope she'll enjoy the summer, for she is worried about her mother, who is ill at some baths in Germany."

"Thus far, Amy, you haven't offered a single reason for your desire to banish us from your side. Neither Taps nor I will stand in the way of your mother's sketches, except to pose for her when she asks. We certainly won't deprive the air of its invigorating qualities; and we might even study—"

"No, Fritz, you'd simply be in the way."

"I won't admit that, Miss Amy Redmond, and if I should ask your mother, she would probably say that you are quite wrong in your opinion. In fact, that's why you won't let me talk with her. However, as you've extorted a promise from me, Taps and I will go as far away from you as we can—in Nova Scotia. We'll travel in the opposite direction from Acadia, for Nova Scotia is large enough to contain us all without a collision. But mark my words, many a time in the next few weeks you'll sigh for a manly arm to pull you out of your difficulties. Then you'll remember me."

"I'm not afraid. Acadia has no dangers. Even the Micmacs are tamed. The French and Indian wars are over."

"That reminds me,—please excuse me for interrupting,—you will find Digby, where you are going to-morrow, very tame compared with Pubnico."

"Pubnico?"

"Yes, Pubnico, a wonderful French village, with Acadians and descendants of the old noblesse, and with many interesting things that you'll miss altogether in your misguided course. Then we shall go to the deserted Loyalist town, Shelburne, which is full of history and haunted houses."

"You seem to have digested a whole guidebook, Fritz. As Shelburne is on the opposite side of the peninsula, I suppose that you really have not intended to travel with us."

"Oh, I had two strings to my bow, and when I heard of the French villages, I decided that to visit them would be the next best thing to do." Then, looking at his watch, "But now I really must say good-bye; it's past my time for meeting Taps."

"Good-bye, Fritz." Amy held out her hand amicably. "You are not angry, are you?"

"No, not angry, only—I may never forgive you. Certainly I shall not forget."

Before Amy could reply, Fritz had wheeled away, and, turning a corner, was soon lost to sight. As Amy walked a few steps along the hotel piazza, suddenly she met her mother face to face.

"Where's Fritz?" asked Mrs. Redmond. "I expected to find him with you."

"Oh, he's gone. It's settled that the boys are not to come with us."

"But, my dear, I hope you have not sent him off. Sometimes you are too abrupt."

"Why, mother, I thought that you did not wish them to come with us."

"I was certainly surprised to see Fritz on the boat last evening. But he is like my own son, and if he has set his heart on going to Digby, we must not keep him away."

"Oh, he's going around on the other coast, he and his friend."

"Did you meet his friend?"

"No, I heard Fritz call him 'Taps'—a perfectly ridiculous name. Do you know anything about him?"

"Only what Fritz told me last evening—that he was a Freshman who had taken a violent fancy to him. Fritz said that he had agreed to travel with the boy this summer from a sense of duty."

"A sense of duty!"

"Yes; 'Taps,' as he calls him, has been trying to shake off some undesirable friends. He gave up a trip to Europe that he might avoid running across them, and Fritz, knowing the circumstances, thought that he could do no less than agree to take some other trip with him. It was only on the spur of the moment that they decided to come with us."

"Fritz was terribly cut up to find that we did not care to have them."

"Naturally—and indeed, Amy, if I had had a chance to talk frankly with him, we could have had them with us part of the time. His friend was a bright, honest-looking lad, hardly more than a schoolboy."

"Oh, mamma, I thought him so dandified!—just the kind to be a nuisance in a party that intends to rough it."

"Do you realize, Amy, that you use much more slang than before you went to college?"

"That's another reason for not having Fritz with us; it is not my college, but his, that twists my vocabulary."

"Possibly, but I only hope that he is not offended. Well! well! Why, Priscilla, why, Martine, where have you been?"

As she spoke two young girls came running up the steps, and one of them with a bound flung herself upon Mrs. Redmond's neck.

"Oh, isn't it a perfect morning, so cool and salt-smelling! and it's almost as good as Europe to see a foreign flag floating from the hotel—even if it is only English. And isn't Yarmouth a dear sleepy old town, though it's said to be so American! Some one told me that it was the only place in Nova Scotia where they hustled. My, but I wish they could see Chicago! Then they'd know what 'hustle' means."

"Yes, my dear," gasped Mrs. Redmond; "but would you move your arm—just a little? You almost choke me."

"Please excuse me, but I feel so excited that I must hug somebody, and Priscilla and Amy never let me hug them."

"Why, I'm sure—" began Amy.

"Oh, no, you haven't said a word, that's quite true, and I've never even tried to embrace you, yet I'm perfectly sure that you would hate it, and so Mrs. Redmond—"

"Is the victim," rejoined Amy. "Well, mamma is amiable. Only, while we are travelling, do be careful not to squeeze too tightly; it rumples her stock. Mamma, you'll really have to put on a fresh one before we start out."

During this conversation Priscilla had been silent. She was shorter than Martine, and fairer, and her expression was sad, or querulous,—at first glance it was hard to say which. Yet her half-mourning costume—the black skirt, and the black ribbon at her throat—suggested what was really the case—that Priscilla had had some recent sorrow.

"What have you been doing, Priscilla?" asked Mrs. Redmond, noticing the young girl's silence.

"Doing!" interrupted Martine, before Priscilla could speak. "Only think how silly she's been. This beautiful morning—and in a new place—she has spent writing letters. Isn't she a goose?"

"Oh, Martine!" and Amy shook her head in reproof.

Priscilla colored deeply as she turned apologetically to Mrs. Redmond. "I promised mamma to write as soon as I could. She will get my letter day after to-morrow."

"You were very considerate to write promptly. Your mother will be delighted to hear so soon. But where have you been, Martine?"

"Oh, rambling a little; I just couldn't stay in the house."

"It's strange, Martine," added Amy, "but a while ago, when I took a stroll down the road, I saw a boy and a girl wheeling down a side street together who looked so like you."

"Which, the boy or the girl?"

Disregarding Martine's flippancy, Amy continued: "I realized that it couldn't possibly be you, as you know no one in Yarmouth."

"And didn't bring my wheel with me," added Martine. "So please, Miss Amy Redmond, don't see double, or else before I know it you'll have all my faults magnified to twice their size."

While Martine was speaking, Priscilla looked at her closely. But Martine, if she felt Priscilla's eye upon her, showed no embarrassment. Instead, she burst into a peal of laughter that woke from his slumbers a quiet old gentleman dozing over his newspaper in a piazza chair.

Martine's laughter quickly degenerated into a giggle, and with only an "Excuse me, I can't help it," she rushed into the house.

"There, mother," said Amy, "I fear that Martine will be a greater care to us than we expected. If she hadn't run off I was going to suggest that we all go for a walk, to see what there really is to be seen in the town. We'll have plenty of time before dinner."

"I'll get my hat and bring Martine with me;" and Mrs. Redmond left Priscilla and Amy by themselves.

A little later the four travellers were walking up the broad street, partially shaded with trees, through which they had many glimpses of the blue harbor.

"Isn't it strange," said Priscilla to Amy, "to think that this time yesterday we were half-stifled with Boston heat! They said that it was the hottest day of the season, and it is probably as hot there to-day; and here we are—"

"Ready to shiver," interposed Amy. "You should have brought a coat, Priscilla, for I almost feel an east wind."

"Oh, the air is soft. There's no danger of catching cold. Do you notice all the flowers in these little gardens? It's a pleasant air, like the Shoals, and those hawthorn hedges make me think of England,—at least, what I've read of it, for I've never been there. We must ask Martine."

"You are almost as eloquent as Martine herself." Amy turned toward Priscilla with a smile. "You were so quiet at breakfast, and indeed all the morning, until now, that I feared you were not enjoying the trip."

"Well, to be honest, I felt homesick at first. You see, I have never been away before without any of my family, and then I hadn't got the motion of the boat out of my head. But now I feel perfectly well, and perhaps—" but here Priscilla's voice was not quite steady—"perhaps I shall not be homesick."

Amy drew Priscilla's hand within her arm.

"Of course not. Naturally, you will miss your mother and the children. But you'll go back to them with such red cheeks, and so many interesting things to tell, that you will be glad you had courage to come away. You mustn't be homesick."

"Oh, I won't be," said Priscilla,—"that is, if I can help it; but if I didn't know you much better than Martine, I think that I'd have to go home."

Whereupon Amy, perceiving that Priscilla was not yet herself, strove to divert her by telling her little incidents of early Nova Scotian history. Her device was successful, and by the time they had overtaken Mrs. Redmond and Martine, Priscilla was quite cheerful again.

In their walk they had turned aside from the main street, and had reached a point on the outskirts where elevated land gave them a good view of the water. Mrs. Redmond and Martine had found a large flat rock, on which they seated themselves, and Mrs. Redmond was already at work with her sketchbook before her.

"I'm glad that you've come, Amy,—I mean Miss Redmond," began Martine. "I've been trying to tell your mother about some kind of a queer stone that I heard some people talking about at the breakfast-table to-day, but I haven't it quite clear in my mind, and so I'm waiting for you to help me out."

"Oh, the runic stone?" asked Amy. "There isn't so very much to tell about it, except that it was found more than seventy years ago, and is thought by some people to be a memorial of the Norsemen."

"The Norsemen in Nova Scotia? But why didn't they discover the stone before?"

"It was found by a Dr. Fletcher in a cove on his own property. The inscription was on the under side, and showed signs of great age. There, I believe I have something about it here;" and pulling a small notebook from her pocket, Amy refreshed her memory.

"Yes, it weighed about four hundred and fifty pounds, and some antiquarians have translated the inscription, 'Harki's son addressed the men.' It seems that there was a man named Harki among those Norsemen who sailed along the coast of America in 1007."

"That is certainly worth knowing," said Mrs. Redmond, "and I hope that we can see the stone before we go."

"Well, it's only fair," continued Amy, "to tell you that some learned people do not believe in the Norse theory."

"Perhaps it's like the inscription on the Dighton rock," interposed Priscilla, "that they now think was made by Indians."

"Yes," added Amy, "but the strange thing is that a few years ago a second stone was found about a mile away from the other, and the inscription on it was almost the same."

"Well," exclaimed Martine, "it doesn't matter whether the Norsemen really were here or not, as long as we can imagine that they may have been. I like the romantic part of history, if it gives you something entertaining to think about. It's all the same whether or not it is true."

After which heretical sentiment, Priscilla, Plymouth-born Priscilla, felt herself to be farther away than ever from Martine.

When Priscilla nestled down beside Mrs. Redmond to watch the growth of her sketch, Martine became impatient.

"Let us go back. We've seen everything there is to see in this part of the town, and perhaps I shall have time for a letter or two before dinner."

"I'll go with you," responded Amy. "I have some packing to do."

"Packing?"

"Oh, just to rearrange some of my things."

"Very well," said Mrs. Redmond. "Priscilla and I will wait until this sketch is finished, and then we'll return by the electric car."

"Any one would know that you and your mother are from Boston," said Martine, turning to Amy with a laugh. "I have heard my father say that Bostonians are the only people in the world who take the trouble to say 'electric cars.'"

"What do others say?"

"Why, trolley, of course. They'd laugh at you if you said anything else in Chicago."

"You're pretty rapid in Chicago."

"And you are rather—well, rather slow in Boston."

lost and found

Amy's face was flushed, her hat slightly askew, and she felt even more uncomfortable than she looked. It was all on account of her lost keys. For ten minutes or more she had been bending over boxes, and poking among all kinds of things in the shed near the wharf, in the vain hope that she might find what she had lost. When she had discovered that the keys were missing, Priscilla volunteered to help her find them.

As the discovery had been made at the very moment when the carriage was at the door to take them for an afternoon drive, Amy insisted that the others should go without her, since it was evidently her duty to search for the missing.

"Let me go with you," Priscilla had urged. "When we find the keys we can go sightseeing by ourselves. It will be just as good fun as driving." Thus Amy and Priscilla made their way by themselves to the wharf, while Mrs. Redmond and Martine were driven in the direction of Milton.

"It wouldn't be so bad if it were only my trunk key," Amy had lamented, "but there's a key of my mother's on the chain, and several keys of little boxes—one or two of which I have with me; the others are at home. I am always losing keys."

"You probably lost them after your trunk had been examined this morning. What a fuss about nothing it was! Why, the inspector didn't even lift the tray from my trunk. But we had all the trouble of unlocking and opening our trunks, and in that way I suppose the keys were lost."

Priscilla spoke with more energy than was usual with her. When they reached the wharf, the dignified Custom-House official and the small boys congregated there and in the neighborhood of the train knew nothing about the keys. The inspector remembered seeing them.

"I noticed your party particularly, and you were swinging your keys by a long silver chain. Well, they may have slipped through a crack somewhere, and so the best thing for you is to get a locksmith to fit a key before you go any farther."

Overhearing this advice, one or two of the boys lounging about offered to guide the young ladies to a locksmith. Thus Amy and Priscilla, not in the best of spirits, with hats askew and shirt-waists somewhat rumpled, came face to face with Fritz Tomkins.

"Oh, ho!" he cried mischievously, as the girls drew near. "What a procession! All you need is a drum and a flag."

Turning her head, Amy saw six little boys walking behind her in Indian file. There wasn't much going on at the wharf, and evidently all had thought that there would be some fun in conducting the American young ladies to the locksmith's.

Fritz himself, seated in the shade at a shop-door, looked aggravatingly comfortable.

"Why, Fritz!" exclaimed Amy, "I thought you were miles and miles away,—at Pubnico."

"Don't, don't show your disappointment too plainly. We thought that we'd better not start before the train was ready. That will not be for an hour yet. In the meantime, is there anything that I can do for you? You look a little like a lady in distress."

"Well, then, appearances are deceitful." Amy had recovered from her astonishment at seeing Fritz.

"I am sure that you are hunting for something."

"Why are you so sure?" Amy was determined not to tell.

"She is looking for something, isn't she, Priscilla?" Fritz had seen more or less of Priscilla in Boston the past winter, and naturally called her by her first name.

Priscilla shook her head,—not in dissent, but to show that she had no intention of disclosing more than Amy herself chose to explain.

"Very well," continued Fritz, "I am a mind reader. I can tell you all about it. You are looking for a bunch of keys."

"How did you know?" For once Amy was off guard.

"Ah! Then it's true."

"Very well, since you know so much, where are the keys?"

Fritz, thrusting his hand in his pocket, drew out a long silver chain, which he swung around his head in a circle before laying it in Amy's hand.

"There, little boys, you—"

"Don't call them little boys, Amy; remember how I felt when I was ten."

"Here, young men." As Fritz spoke the boys drew nearer, and Fritz, drawing from his pocket a handful of silver, laid in each of six palms a bright ten-cent coin with the Queen's head stamped upon it.

"But we didn't do anything," one of the six managed to say.

"No, but you would have helped the young lady find a locksmith, and besides, you brought her to the particular spot where I was sitting, and so you found her keys for her."

This logic was so correct that the six boys, feeling that they had earned the money, rushed off with a shout of "Thank you," to find the quickest way of spending it.

"You might have brought the keys to the hotel," complained Amy. "Then I needn't have had this dusty walk."

"After the summary way in which you banished me this morning I certainly could not put myself in your way again. But I knew that when you came to dress for the afternoon you would miss your keys, and happen my way. Surely you can't object to my being here?"

"Of course not. I am very much obliged to you."

"Besides, I found the keys only this afternoon. They had slipped under a board, and when I saw the end of the chain I recognized it at once. May I walk with you part way up-town? I'm sorry that I can't go all the way. But Taps and I have an errand to do, and it's now within an hour of train time. Remember, you have banished us."

As they walked, Fritz, abandoning frivolity, outlined his plans for the next week. Priscilla listened with great interest. Nova Scotia was indeed a new land to her, and as she had rather suddenly decided to accompany Amy and her mother she had read nothing on the subject of the province in which they were to spend a few weeks.

Fritz had known little more than Priscilla until he had stumbled on some one crossing on the boat the preceding night who had had much to say about the old Fort La Tour and its neighborhood.

"Fort La Tour!" Amy exclaimed. "I shouldn't care to discredit your history, but I am sure that that was on the River St. John across the Bay, in quite the opposite direction from where you are going."

"There, there, my dear Miss Amy Redmond, you are just like other people. Because you know some Acadian history you think that you know it all. There certainly was a Fort La Tour at St. John, but its remains, I hear, are altogether invisible now; whereas the first Fort La Tour can still be seen in outline, at least. There isn't any masonry, I believe, yet you can trace the outline in the grass. You remember, Amy, it was once called Fort Loméron."

"I'm sorry, Fritz, but I don't remember. You must have taken a special course in history lately."

"Yes, this very morning. You see I had time to spare after you sent me into exile, and Taps and I were to have our dinner at a private boarding-house, where I thought we ought to stay, since you didn't care to have us at the hotel. Well, to make a long story short, I found a set of Parkman there, and it seemed wise to refresh my memory before going down to Port La Tour."

"Do tell us what you learned." Amy spoke eagerly. "I'll admit that I've quite forgotten the first Fort La Tour."

"I haven't much time now," said Fritz, "but I'll do what I can to make my knowledge yours,—only you mustn't expect me to be perfectly accurate. This, however, is the way I figure it out. After that old rascal, Argall, attacked Port Royal, in 1613, Biencourt, or Poutrincourt, as he was known after his father's death, wandered for years in the woods with a few followers, sleeping in the open air, and living on roots and nuts like an Indian. In some way or other he managed to get men enough, and material enough, to build a small fort in the Cape Sable region, that he called Fort Loméron,—a rocky and foggy neighborhood. But there was fine fishing and hunting, and he felt that the Fort was a warning to any enemies who might try to take away the rest of what his father had left him. Well, among his followers was young Charles de Saint Étienne de La Tour, who also had come out to Acadia as a boy. When Biencourt died La Tour claimed that Acadia had been left to him by his friend. He tried to get Louis XIII. to help him against the English, and against Sir William Alexander in particular, to whom James I. had granted Acadia. Now young Charles La Tour began to have a hard time because his father Claude had married a Maid of Honor to Queen Henrietta Maria, and had promised Charles I. that he would drive out the French and establish the English in Nova Scotia. But when Claude appeared with his two ships before his son's Fort, he could not persuade him to turn color and become a Baronet of Nova Scotia. The father made great promises in the name of King Charles if the son would surrender, but the son withstood the father, and the latter lost English support because he had not been able to keep his promise; and so he was nothing but a refugee the rest of his life."

"Served him right for deserting his country," murmured Priscilla.

"Well, it's hard to understand just who did what in those days, and why. Some say that Charles La Tour was no better than his father, and that he, too, accepted from the English the title 'Baronet of Nova Scotia.' On account of the conquest of Sir David Kirke, Nova Scotia was English for a while, and then again it was under the control of the French after Claude de Razilly brought out an expedition in 1632. Charles de Menou d'Aunay, by the way, La Tour's great enemy, came with Razilly. But La Tour made haste to put himself right with the King of France, and, after a visit to Paris, came back to Nova Scotia 'Lieutenant-General for the King at Fort Loméron and its dependencies, and Commander at Cape Sable for the Colony of New France.' Doesn't that strike you as quite tremendous, when you think of the rocks and the fogs and the seals, together with the forests, that chiefly made up his domain?"

"It's very interesting," said Priscilla. "What became of La Tour?"

"It's a long story," responded Fritz. "I'm afraid I haven't time to tell it now."

"Oh, I know all about his quarrel with D'Aunay," interposed Amy. "It will come in better when we are at Port Royal—or rather Annapolis. But I had forgotten this Fort near Cape Sable."

"You shouldn't have forgotten it." Fritz's tone deepened in reproach. "For many of La Tour's descendants live near the Fort, and the place itself is called Port La Tour. I am astonished that you should have left it out of your plan of travel. You can't go there now, because that is where Taps and I are bound, and it wouldn't do for us to get in your way—I mean for you to get in our way. Beyond the tip end of Nova Scotia there's Sable Island, that used to be haunted by pirates and privateers. Some of them may be there still, and if Taps and I go there, and if anything happens to us, you may be sorry that you drove us away. Good-bye, Amy; even a Nova Scotia train won't wait for me;" and before the astonished girls could say a word, Fritz, with a touch of his cap, was walking rapidly away from them.

"We haven't offended him?" asked Priscilla, timidly.

"No, indeed. His plans were already made to go among the French villages. In fact, I thought that he had gone this morning. He started off soon after breakfast."

Although Amy spoke thus decidedly, secretly she wished that she had been less summary with Fritz. It was not strange, indeed, that her conscience should prick her a little. When she and Fritz were not yet in their teens they had become acquainted at Rockley, a summer resort on the North Shore where Fritz spent the summers with his uncle. Rockley was Amy's home all the year, and as not many boys or girls of her own age lived near her, she greatly appreciated the companionship of Fritz. The latter, for his part, knew that he was very fortunate in having the friendship of Amy and her mother; for, like Amy, he had neither brothers nor sisters, and although his father was living, his mother had died when he was a baby. His father spent little time with him, as he was fond of exploring new countries, and his travels often kept him away from home two or three years at a time.

Before entering college Fritz had lived with his father's elder brother,—a serious, scholarly man. The uncle made little provision for amusement in his nephew's life, until Mrs. Redmond had shown him that all work and no play would do Fritz more harm than good. Amy and Fritz, on the whole, had been very congenial friends, although the latter could rarely resist an opportunity to tease Amy. Mrs. Redmond often had to act as peacemaker, and Fritz always took her reproofs good-naturedly. No one knew him so well as Mrs. Redmond did. There was no one to whose words he paid quicker attention. He called her his "adopted mother," and naturally it seemed strange to him that she should agree with Amy that he and his friend would be in the way on the Nova Scotia tour. Beneath the jesting tone that he had used with Amy lay something sharper, and Amy, as he finally turned away, realized this.

After the departure of Fritz the girls walked on in silence. Suddenly an exclamation of Priscilla's brought them to a standstill. In the window of a little shop were two cups and saucers of thickish china, decorated in a high-colored rose pattern. The cups were of a quaint, flaring shape, and Priscilla announced that she must have them. There were other curiosities in the window,—a small cannon-ball, two reddish short-stemmed pipes, and many things of Indian make. The shop-keeper proved to be an elderly woman, with a pleasant, soft accent. The cups, she explained, had belonged to an old couple who had lately died, leaving no children. At the auction she had bought a few bits of china.

"I know they are old,—more than a hundred years,—these two cups. I'm sorry I haven't any more, but people from the States are always looking for old things, and there's been a good many here this summer."

Priscilla bought the cups, and Amy inquired about the cannon-ball.

"It was dug up near Fort St. Louis, as some call it, or Fort La Tour, and the pipes too. They say there's many a strange thing buried there under the ground, if people only had the patience to dig."

Amy decided that it was hardly wise to burden herself with the cannon-ball, and she didn't care especially for the pipes.

"There's something else here," said the woman, "if you won't be offended at my showing it. Some Americans—"

"How did you know that we were Americans?" interrupted Amy.

"Oh, as soon as ever a Yankee—there, I beg your pardon—any one from the States opens her mouth—"

"She puts her foot in it," returned Amy, with a smile.

"No, no, I wouldn't say a word against the accent, but I can always tell it. I have a sister married in the States, and her children speak like their father. When they come to visit me I tell them that they are regular Yankees. Not that I have anything against that; I hope I'll live to see Boston some time."

"Have you never been there?" asked Priscilla, in surprise.

"No, Miss; I know that it isn't so far away, but I was born in the Old Country, and when I take a trip, that's where I'd rather go;" and the little woman sighed. "But I'll show you the curiosity I spoke of."

From \[Pg 25]a drawer behind the counter she drew a small fan, one or two of whose sticks were broken, while the silk was faded and torn.

"I bought that from an old lady who said that her grandmother fanned an officer who was wounded at the Battle of Bunker Hill, while he lay sick in her house after the battle. Perhaps I oughtn't to speak of it," she concluded apologetically.

"Why not? The war's entirely over, and no one has any feeling about it now."

"I suppose not." But the woman's voice carried a question.

"Why, to prove that I have no resentment I'll buy the fan,—even if it did once soothe the brow of a hated Britisher." Amy smiled at Priscilla as she spoke.

The price named came so well within Amy's means that she half doubted the authenticity of the relic. Of her doubts, however, she gave no hint to the talkative little Englishwoman. Instead, by what she afterwards called a genuine inspiration, she asked some question about the French people at Pubnico.

"Oh, they are good enough," said the woman, "and spend plenty of money in Yarmouth; and there's many of the young people working here in our shops and mills, although many French come from Meteghan and up that way."

"Meteghan?" queried Amy.

"Yes, that's a pretty country up North on St Mary's Bay, and all French. If you're going to Digby you'd better stop off."

"But we were going straight through to Digby."

"Yes, most people go straight through, and don't know what they miss. You see, the natives up there are Acadians, and it's kind of foreign like, for they mostly speak only French. My husband and I, we went up there once and stayed at the hotel, for he had an order for some goods that he had to see about himself."

While Mrs. Lufkins was talking the practical Priscilla had taken out her notebook, in which she wrote the name of the station and other things that would help them.

"Do you think that your mother would like to change her plans?"

"Yes, indeed; she will think this just the thing. Probably there will be good material for sketching,—scenery, and odd people, and all that kind of thing. I am sure that she will like it."

"Thank you, Mrs. Lufkins," said Amy, as they turned away from the mistress of the little shop; and then in a particularly cheerful tone she added to Priscilla, "I feel as if I had found a gold-mine. Fritz was so very sure that he was to have a monopoly of the only French in Nova Scotia, that it will be great fun to write him about our French people."

"Then you think you will go there?"

"Certainly; mother will enjoy it, and it will be great fun for the rest of us. Wasn't Mrs. Lufkins entertaining? If she were Yarmouth-born, perhaps she wouldn't speak of us as Yankees. You know the first permanent settlement here was made about 1761, by Cape Codders. In fact, the name's from Yarmouth on the Cape, not from the English Yarmouth directly. I remember the names of two of the first settlers,—Sealed Landers and Eleshama Eldredge. Don't they sound like real old Puritans?"

"But how did they come to be English? Why didn't they stay on our side in the Revolution?" Priscilla's tone contained a whole world of reproach for Sealed and Eleshama.

"Oh, that's a long story. I dare say they were on our side—in their hearts; but they couldn't afford to give up all they had worked for, after coming here as pioneers. Many of the Yarmouth people were thought to be in sympathy with the American privateers that were always prowling about the coast. But the English managed to hold Nova Scotia, and in the War of 1812 the number of American vessels captured by Yarmouth was greater than the number of Yarmouth vessels captured by the Americans."

"When I left home," said Priscilla, "I did not know that there was so much history down here. I thought that we were just coming for change of air."

"Oh, the place is alive with history; only you must let me know if I bore you with too many stories."

"You could never bore me." Priscilla laid her hand affectionately on Amy's. She was an undemonstrative girl, though her likes and dislikes were well known to herself. But for her fondness for Amy she would hardly have made one of this summer party.

toward meteghan

Amy rested her hand on her bicycle, waiting to mount.

"I did not think that it would be quite so lonely; but still, you're sure it's perfectly safe?"

"Oh, yes, Miss, and not a long way." There was a trace of accent in the speech of the man who replied to Amy's question. He had just deposited a pouch of mail in the vehicle in which sat Mrs. Redmond, Priscilla, and Martine, and had turned to adjust the harness of his meek-looking horse.

"You are not afraid, are you?" Priscilla's voice was anxious. "I wish that I had brought my bicycle, and could ride with you."

"You do look like a maiden all forlorn,—spruce trees to right of you, spruce trees to left of you. Excuse my smiling;" and Martine's smile lengthened itself into a decided giggle.

"Don't," whispered Priscilla. "The driver will think that you are laughing at him." It always surprised her that Martine should show so little respect for Amy, who was several years her senior.

"Amy," interposed Mrs. Redmond, "do you object to our driving away and leaving you? Doubtless if we tried, we could find some kind of a conveyance to carry you and the bicycle."

"Not till after dinner, Madame." Their driver turned toward Mrs. Redmond, lifting his hat politely,—"Every horse is away now."

"The only thing for Amy to do is to let you hold her on your lap, Priscilla, while I take the bicycle on mine." At which absurd suggestion even Priscilla was forced to laugh; for the vehicle sent down to Meteghan station for her Majesty's mail was as narrow and shallow as any carriage could well be that made even a pretence of holding four persons. But with the deftness that comes with experience the driver had managed to find room not only for his passengers, but for their suit case and bags, for several packages that had come by train, and finally for his great pouch of mail.

"There must be a perfect cavern under the seat," whispered Martine to Mrs. Redmond. "I am sure that we could put Amy there."

But even as she spoke Amy had mounted, and was up the hill ahead before the driver had taken his seat. Yet although Amy had taken the hill so well, she was soon out of breath. The road was soft, and the hill steeper than she had thought, and when a little chubby boy darted directly toward her, she slipped from her wheel and bent down to talk to the little fellow.

To her surprise, at first he did not respond to her "What's your name?" but hung his head shyly. Then it occurred to her that he did not understand, and when she repeated her question in French his "Louis, Mademoiselle," showed that her venture had been right.

"Does every one here speak French, Monsieur?" she asked, as the carriage approached.

"Yes, all," responded the driver, stopping beside her for a moment.

"And no English?"

"Oh, many, though some have no English."

Martine and Priscilla praised the bright eyes of little Louis. Mrs. Redmond handed him an illustrated paper that she had brought from the train, and the driver started up his horse.

"You follow me," he called back to Amy.

"Yes, yes," cried Amy, laughing, knowing that she could soon pass him; but while she loitered to talk with the child, the carriage was soon so far ahead that she could barely discern the fluttering of the long veil that Martine held out to stream in the wind like a flag.

After leaving little Louis, Amy pedalled along leisurely. At first she passed only one or two houses, but each of them offered her something to think of. In front of one, two or three barefooted children were playing hop-scotch, with the limits marked out in lines drawn by a stick on the dusty road. "I should think they'd stub their toes," she thought, as she watched them, "but they're so well-dressed, except their feet, that I suppose they prefer to go without shoes."

In the doorway of a second cottage, set like the other, close to the road, a mother was standing with a baby in her arms, and a tiny little girl clinging to her skirts. These children, like all the others she had seen, had the brightest of black eyes. Beside the door was a well, boarded in, with a bucket beside it.

The woman looked so friendly that Amy stopped for a drink of water, and, making use of her best French, she spent a few minutes talking with the woman.

A fine team of oxen hauling an empty hay wagon, beside which walked a strapping youth in blue jeans and a flapping straw hat, was the next reminder to Amy that she was indeed in a foreign country. After she had returned the cheerful bonjour of two or three bareheaded women whom she met trudging along toward a hayfield, Amy was recalled to herself. Her mother and the others were out of sight. "The driver will think that I am not even following;" and making good speed up a long, gradual hill, she saw the carriage waiting for her some distance ahead.

"This way, this way," shouted Martine. The driver waved his whip toward the left, and when Amy caught up, they had changed their direction, and she could feel the soft fresh breeze blowing in from St. Mary's Bay.

"Did you ever see such a clear blue sky?"

"Oh, yes, Martine,"—Amy was thinking of cloudless days on the North Shore,—"but none bluer, perhaps."

"But it seems so foreign," interposed Priscilla, in a tone that expressed some disapproval of foreign things. "I'm not sure that I like it."

"It seems different from other places, though I can't tell why."

"This child is part of the why. Just look at him." Martine pointed to a little boy of about eight, dressed in black, with deep embroidered ruffles of white falling about his wrists, and a broad ruffled collar on his coat. He wore a hat that was something like a tam-o'-shanter, and something like a mortar-board, and he carried a large slate under his arm.

"He's evidently on his way home from school. See the crowd of children behind him."

As the children drew nearer, some stood still, the better to see the party of strangers. Thus the latter had a chance to note various peculiarities of dress and general appearance. One or two little girls wore sunbonnets, one or two wore hats, and several had on their heads black couvre-chefs, that made them look like little old women. The sturdy little boys in blouses were more like other boys, and they indeed were too busy racing and tumbling over one another to pay attention to the travellers.

"Amy," exclaimed Martine, "you should have kept beside us all the way, we have been hearing such wonderful stories. Down there by the bridge there are several descendants of the Baron d'Entremont, and other people whose ancestors came from France hundreds of years ago."

"The Baron d'Entremont!" Amy felt a thrill of pleasure. Surely that was one of the names that Fritz had mentioned in connection with Pubnico, and if she too could come across some of his descendants, how delightful this would be!

The houses were now nearer together than they had been. At the right there was a glimmer of blue water. On the bridge at the foot of the decline Amy dismounted to watch the men loading with lumber a little schooner at the wharf near-by. The carriage drew up before the tiny post-office, where part of the mail was left. A gray-bearded man in the door of a small shop caught Amy's eye. With his broad-brimmed hat, loose trousers, and slippers,—yes, slippers,—he reminded her of pictures she had seen of old Frenchmen. She longed to snap her kodak, to catch him just as he stood there, leaning on his cane. But she did not dare, there was something so very venerable and dignified in his appearance.

Then her eye fell on the name d'Entremont over the shop. Martine and Priscilla joined her. Martine was in great spirits.

"Your mother is writing a post-card in the office. So, while we are waiting, let us go in here and try the d'Entremont brand of ginger ale. They're sure to have some, and one doesn't often have the chance to patronize the descendant of a French nobleman."

Within the dim little shop two or three men were lounging near the counter, who probably said to themselves, "Oh, those foolish Americans!"

But their manner showed no disrespect as they moved aside, and the proprietor made one or two pleasant remarks as he served the trio.

A few minutes later Amy was again on her bicycle, the others had taken their places in the carriage, and the little village was behind them. The large farms that they had seen near Meteghan station gave place to small gardens. The houses were near together, and they were painted in colors that drew many exclamations of approval from Martine. "This is great! I never dreamed that I should see a lavender cottage with green trimmings,—and what a shade of yellow for a house! Oh, Mrs. Redmond, I hope that our water-colors will last the trip. I'm afraid that we'll use them all up, painting the wonders of Meteghan. This is Meteghan, isn't it?"

"Yes, Mees," replied the driver. "It was all Meteghan, from the station, only that was a different name for the other post-office. But there is our church; this is the true village."

"Star of the Sea" was an imposing building, but the journey since leaving Yarmouth had been long, and they were too eager now to reach their destination to give the church more than a passing glance.

Amy's quick eye had noted the swinging sign of the little inn not so very far beyond the church, and, hastening ahead, she was the first to be welcomed by Madame, wife of their driver, who was also proprietor of the small hotel.

Welcomed with ceremonious politeness, they were soon made to feel perfectly at home. When the question was pressed, they all admitted that they were very hungry. In the pleasant rooms to which they were shown, they had barely time to make themselves ready when a loud bell called them to dinner. As the four entered the dining-room, they saw that there were several other guests at the long table. One, a stout man with a fondness for jokes, proved to be the agent for a millinery house in Halifax. There were one or two others who said so little that even Amy could not tell whether they were French or English; two middle-aged ladies near Mrs. Redmond quickly let her know that they were teachers from Connecticut, now for the first time making a tour of the provinces. They had sailed from New York to Halifax for the sake of the sea voyage, and had come down slowly through Windsor, Grand Pré, and Annapolis, and were enthusiastic about all these places.

"But if you can," one of them concluded, "you must have a few days at Little Brook,—Petit Ruisseau, as some call it. It's the centre of everything interesting in Clare; it's really where the first Acadians landed after the expulsion, and only a short distance from Point à l'Église."

Amy listened eagerly. Here evidently was some one who could tell her much that she wished to hear about this new country, and later, when they were all outside on the little piazza at the front, she learned what she wished to know. On consulting her mother, they decided that after a day at Meteghan they would go on to Little Brook, and spend at least two or three days there—if possible at the Hotel Paris, which the teachers recommended.

Missing Priscilla and Martine, Amy found them in the little sitting-room.

"Tell me," whispered Martine, "aren't you disappointed?"

"Disappointed with what?"

"Why, in this house—this room especially; it's so—so unforeign."

Amy glanced around her,—at the bright-flowered carpet; the marble-topped table, on which was displayed a bouquet of wax-flowers under a glass globe; on the two machine-made oak rockers; and then on the pictures.

"Where do you suppose they found that picture of the Queen with such very pink cheeks, and a mouth as small as a pin, and those wax-figure princelings—and those saints? Do you suppose Madame and her children know the names of them all?"

At that moment Madame herself entered the door.

"You like pretty things. Ah, you must see my rugs, if you would care to."

"Yes, indeed," Amy replied politely.

"Then come with me. They are in my room,—the best,—and the American ladies always admire them."

So the two girls followed their landlady upstairs, where she proudly displayed rug after rug of wonderful design and still more wonderful color. Martine dared not say what she thought,—that it seemed a pity that so much time had been put into things that could only dazzle rather than please the average beholder. Amy conscientiously praised those that could be properly praised,—for here and there was a rug of really artistic design,—and Priscilla gave an exclamation of delight as she noticed on the bed a really exquisite spread.

"You like that?" asked Madame. "It is good work, all by hand; only two or tree women can now make them. My old aunt who made that is dead, but—"

"It is like the finest Marseilles, only I never saw so beautiful a pattern. I did not know people could make such things by hand."

"On a loom, surely yes; there are only one or two in Meteghan, but you can see one work, if you wish, at Alexandre Babet's."

"There, that will be something to see! Is it far?" cried Martine.

"Oh, no. You can find it quickly."

"After we are rested," responded Amy. "The sun is still hot. Your rugs and the spread are beautiful."

As the girls sat down on the piazza, Priscilla turned to Amy. "You did not think those rugs really beautiful?"

Amy did not resent this slight touch of reproach, even though Priscilla was so much her junior.

"Yes, and no. Some of them were beautiful even from my point of view. They all were from that of their owner, and since she desired to please us by showing them, it seemed only fair to reward her with a word of praise."

"But if every one praises her she will go on using those terrible aniline colors. They made my head ache just to look at them."

"Oh, Priscilla, you are so precise I'll call you 'Prim' as well as 'Prissie.'"

"No one else calls me 'Prissie,' Martine."

"No one else dares tease you. Probably your little brothers and sisters are frightened to death of you, and then, because you are the oldest, you have always been made to think that you are absolutely perfect."

"Oh, Martine!"

"There, there, I know just how it is. It's so in our family; I have an elder brother, and he has always been held up as a model, although, between you and me, he's far from perfect. It just keeps me busy, showing him his faults. So, Miss Prissie, if you are too old-maidish I'll have to show you yours."

Priscilla was helpless under Martine's rapid fire of words. In her moments of reflection it surprised her that a girl whom six months before she had not even heard of, should now venture to say things to her that no one in her own family would dare to say.

A little later, Amy and Priscilla and Martine set out to see the loom that made the fine quilts. Priscilla had desired to postpone the visit until next morning. "It would be better to rest now."

"I'm tired resting," protested Martine. "Unless we move on, I will go indoors, and play doleful things on the melodeon. You don't know what I am when I'm melancholy."

Unmoved by Martine, when Amy showed that it was better not to spend the whole afternoon listlessly, Priscilla objected no longer.

The Babet house was a ten minutes' walk up the street. After mistaking one or two houses for the one they were seeking, their third trial brought a tall, long-bearded man to the door who answered to the name of Alexandre Babet.

"We hear that some one here—your wife, perhaps,—makes those beautiful quilts."

"Oh, yes," responded Alexandre, in fair English. "They are good quilts, and we have a loom."

Martine pinched Priscilla's arm. "I'm disappointed; I thought that he'd speak French."

"Come in, come in;" and Alexandre showed them into the neatest of sitting-rooms,—neat, but painfully bare. It was brightened, to be sure, by one or two gay pictures of saints in brilliant-colored garments, and by two or three geraniums in flower on the window. But the wooden floor was unpainted, and on it was only one rug, and there was little furniture besides the high dresser and a long table.

Alexandre went off to summon his wife, and soon she came in from the kitchen, accompanied by another, whom Alexandre introduced as his sister. The girls soon became embarrassed under the piercing gaze of their black eyes. The women wore dark calico gowns with little shawls over their shoulders, and their couvre-chefs were bound closely to their heads. Neither of them understood English, nor spoke it. But Alexandre proved as talkative as any two women. Moreover, he occasionally translated his own words into French, and in the same way made the women understand what the young American girls said—to the great amusement of Amy and Martine. Priscilla sat solemnly through the conversation, as if she found something pathetic in the aspect of the women.

During a moment of silence, when the room seemed rather close and uncomfortable,—for the windows were shut, and the blinds were drawn,—there came a gentle tapping on the door. Madame Babet sprang to her feet.

"No, no, sit still; she can come in." Then turning to the others, Alexandre added, "It is Yvonne, our little one. Come in, Yvonne," he called in a louder tone; "here are Americans."

Upon this the door was pushed open, and a little girl wearing a pink gingham gown and a white sunbonnet, entered slowly, holding one hand outstretched, as if not quite sure of herself. Then, walking directly toward Madame Babet, she slipped to the floor beside her, and laid her head on her lap.

The girls looked from her to Alexandre to read an explanation in his face, and he, understanding, raised his hand to his eyes.

"Blind!" exclaimed Martine, involuntarily. "Poor little thing!"

"She understands English," said the man, warningly; "she does not wish pity."

"I see much," said Yvonne, proudly, "when the light does not glare. I see the American ladies. This one is pretty;" and rising, she made her way carefully to Martine, and laid her hand confidingly in hers.

Martine's color deepened; she felt a great tenderness toward the girl, and she raised the little hand to her lips.

yvonne

"She is adopted," said Alexandre, "but we know no difference. She calls us her parents. Her mother and father are dead, and she makes her home with us since she was a baby. When I get my gold out she shall sing, oh, so beautifully."

"Your gold out?" queried Amy.

"Ah, yes! Back here on my farm, which looks all rocks, there is much gold underneath. I know not how to get it out, but some day I shall find a miner who knows. See!"

From a drawer in the dresser he brought out two pieces of quartz, which he asked the girls to look at carefully. "It is gold underneath, sans doute, and, Mees, if you know a miner in Boston to study this, he could have some of my gold when it is dug out, but as for me I know not how to get it out, and poor Yvonne cannot have her music."

Gradually the girls gathered that Yvonne had a voice "sweeter than an angel's," and that Alexandre had set his heart on giving her a musical education. His plans soared far beyond the Western continent. He would send her to Paris, to Italy, and she should astonish the world. The most of this conversation or monologue took place in the little field back of the house that Alexandre dignified as "my farm." The soil was poor and rocky, and evidently he had hard work to raise the few patches of vegetables needed for his family. There was a tiny orchard,—it had not been an Acadian farm without that. The trees were knotty and scrubby, and Amy was not surprised that the prospect of a gold-mine offered even more than the usual attractions to the visionary Alexandre. But Amy, though she knew nothing of mineralogy, thought it most unlikely that a gold-mine lay hidden beneath the stony surface in which Alexandre had dug a deep, deep hole with a vague idea that it was a shaft. Indeed, Amy felt quite sure that even a mineralogist—for such was the meaning of his "miner"—would give him little encouragement. Yet as she looked at the slender figure of Yvonne walking ahead with Martine, she felt deep sympathy with his ambition.

Evidently Yvonne, in spite of her infirmity, was the pride of the little household. Her print gown of a delicate pink cambric was spotlessly neat, and her white sunbonnet had been laundered with the greatest care. Though much shorter and slighter than Martine, the latter was surprised to find that the little Acadienne was hardly a year younger, and that it was true, as Alexandre said, that she ought soon to have the chance to study—if—and here was the question—if her voice was what he pictured it.

"Miss Amy," murmured Priscilla, half impatiently, "I thought that we came to see the loom."

"Indeed we did, but these people have been so interesting that we have spent too much time out here." Then turning toward their host, who had fallen back, she asked him to show them the loom.

"Ah, yes, with the greatest pleasure,—the loom, and the beautiful quilts that my wife makes, and the lace of Yvonne. The mine did almost make me forget, but we shall go in quick."

When they were again in the house he led them up a steep flight of stairs to an unfinished room, with great rafters overhead and two small windows admitting little light.

There at the loom sat his silent wife, and beside her stood the equally silent sister. So it fell on Alexandre to explain the workings of the great wooden frame. While he was talking, however, the attention of all the girls flagged a little. Amy had never been interested in machinery, and made no pretence of understanding it. Priscilla was impressed by the quaintness of the scene, but she was weary from her two or three days of travelling, and her mind wandered while the voluble Frenchman was talking; and Martine, fully occupied with Yvonne, paid little heed to any one else. Nevertheless they were all sufficiently impressed with the skill with which the rather dull-looking wife of Alexandre managed warp and woof, and produced, even as they were looking at her, a fragment of pattern.

While Alexandre was in the midst of one of his speeches Priscilla whispered to Amy, and Amy, as if at her suggestion, turned to Alexandre.

"We cannot stay much longer," she said politely, "and we are delighted to have seen this loom, so that we can understand how these quilts are made. It's really quite wonderful, your wife is so clever;" and she paused for a moment to watch the busy fingers now flying in and out among the threads. "But we came particularly to see some of the quilts."

"Oh, yes, Mees, certainly, we will show you quick;" then with an eye to business,—"perhaps you will want to buy."

"Yes," said Amy, "perhaps we may. Come, Priscilla; come, Martine."

The two women followed the girls downstairs, and when they were again in the little front room, from a wooden chest in the corner they brought out a large quilt of much more beautiful design than any they had seen.

"I must have that," cried Martine in delight; "it is just what I want."

Then, when a second was shown, she was equally enthusiastic, and then a third was laid on top of the pile.

"The money from the quilts is saved for Yvonne," Alexandre whispered to Amy, and the latter did not protest when four of the quilts were laid aside for Martine. Amy also chose one for herself, but Priscilla, although she praised them, expressed no inclination to buy. Only when some narrow hand-made lace was brought out from the chest did she become enthusiastic, or as nearly enthusiastic as was possible for Priscilla, and Yvonne blushed under her praise.

"It is an old art," the little blind girl explained; "it was my grandmother taught me, and her grandmother taught her, and so on back to the days of old France."

"But how can she do it? She is blind!" exclaimed Amy.

"Oh, not all blind, and not always! She can see a little, though everything is dim, and the lace it is knitted,—not pillow lace, like some,—and she can make her fingers go, oh, so quickly! Ah, she has much talent, the little Yvonne, and you must hear her sing."

So Yvonne sang to them standing there in the middle of the room, without notes and unaccompanied, and the plaintiveness of the tone and the richness of the voice drew tears from the eyes of the three American girls, while father and mother and aunt were lost in admiration as they gazed at the slender figure in the pale pink gown.

Hardly had she finished when Martine, jumping up, impulsively threw her arms about Yvonne's neck.

"You must go back with me to the hotel. You must sing to me again. There is a melodeon in the parlor, and I will accompany you. Please, Mr. Babet, can she go back with us?"

"It is an honor for Yvonne," he replied politely; "I will ask her mother."

"Oh, let me; I will make her say 'Yes'"; and in a few words of rapid French Martine asked that Yvonne might go to the hotel as her guest, to stay to tea. The mother at once assented, and both of the silent women were in a flutter of excitement as they accompanied Yvonne to her bedroom to make some additions to her dress.

"Ah," said Alexandre, "she has never been inside the hotel; it will seem very grand to her."

Then Yvonne, kissing them all,—the mother, the aunt, and finally the tall father,—turned her back to the cottage, and with beaming face leaned on Martine's arm as Amy led the way.

A little distance down the road they saw a man standing by a gate.

"Good-day, little one," he called; "where are you going?"

"To the hotel, Uncle Placide."

"How happens it?"

"These American ladies have asked me. I am to have tea."

"Ah, well, she is a dear little one, and you are good to her."

The whole party had now halted in front of the gate, and these words seemed to be particularly addressed to Amy; for, standing directly in front of her, Placide lifted his hat. "Won't you enter?" he asked pleasantly.

"But, uncle," remonstrated Yvonne, "we have no time; we go to the hotel."

"Oh, but there is much time; I have been in the States, and I like to talk to the strangers, so enter my garden at least, ladies, to taste of my cherries."

There was nothing to do but enter the garden. At the mention of cherries Yvonne indeed had seemed more willing to halt on her way to the hotel, and the others, as Placide thrust upon them liberal handfuls of his great crimson cherries, did not regret the delay.

"You are from Boston," he said, after Amy had mentioned her home. "Ah, I worked in Boston, that is, in Lowell, which was the same, and then I came home when I had saved enough to buy a house. It is not so gay here as in Lowell, but it is happier, and I can make a pleasanter living. I never did like the mill, but the pay was good."

"What do you do now, Mr. Placide?" asked Amy.

"Oh, I fish. The sea is good to us Acadians; it is better than the factory. One gets health here as well as fish, and fish enough to keep the house fed. So, with my potatoes and my cherries, I am rich." Then, with an afterthought,—"But I hope sometime that little Yvonne can go to Boston, where there is much music. She could study and be great singer, for the voice it needs teaching. I know that, because I have been in the States where people study so much."

The girls found it hard to leave Placide, for he was even more fluent than Alexandre, and his years in the States had given him a certain amount of information about things American, and he was evidently fond of displaying what he knew. But at last they managed to say good-bye, and continued their way down the road.

"I am tired," sighed Priscilla, as the four stood at the door of the little hotel.

"Then let us sit here on the piazza. Would this suit you, Yvonne?"

Yvonne turned toward Amy with a smile. "I like whatever the other ladies like; it is all good for me."

"Oh, yes," added Martine, "it will be great fun to sit here and watch the passers-by. Things are rushing this afternoon; two persons are entering that shop across the way, and I can count three ox-carts and two buggies in sight. Where do you suppose the buggies are going?"

"Perhaps half a mile up the road; perhaps to Yarmouth. You know there is a continuous street along St. Mary's Bay, about forty miles from Yarmouth to Weymouth."

"One street forty miles long!" Amy's statement roused Priscilla from her lethargy.

"The young lady says true," interposed Madame, their landlady, who had stepped out on the piazza. "Forty miles, and all Acadians! Is it not marvellous that they have grown to be so much, when the English treated them so cruelly, long, long ago?"

"Ah, yes, Evangeline," responded Martine, politely.

"Evangeline never came back," said the literal Priscilla.

"That is true," assented the landlady. "But there is more than Evangeline to tell about. Little Yvonne here knows many tales."

Yvonne sighed softly. "Ah, yes, very many. But Evangeline lived not in Meteghan. Her country was Grand Pré, far north. You will go there, without doubt?"

"Yes, Yvonne, we shall spend a week there."

"There are not so many stories about Meteghan, for no one lived here until after the exile."

"I remember one," interposed Amy; "the story of Aubrey, who was lost in the woods. At least, some writers say that he was lost in the Meteghan woods, others that it all happened near Digby."

"Tell us the story, Amy, and we can decide for ourselves where it was."

"How like Martine!" thought Priscilla, "as if a girl could decide where to place an historic event!"

"After all," continued Amy, "it's only a little story, but it tells of something that happened on that first expedition to St. Mary's Bay, when De Monts brought his vessels here in 1604, and Champlain named this stretch of water, as he named so many other places. One member of the expedition was Aubrey, a priest, with an intelligent love of nature. A small party went off from the vessel to look for ore along the shores of St. Mary's Bay. The priest was one of the number, but when the boat was ready to return he could not be found. He had left his sword in the woods, and had gone back to look for it. For four days the others searched for him without success, and suspicion fell on one or two Huguenots in the party, in whose company he was last seen. With one of them he had had some rather violent discussions on religious matters. To the credit of all, however, no harm was done to the Huguenots in spite of the suspicion. After sailing without Aubrey, the party went farther north, and it was nearly three weeks before they returned to the neighborhood where he had disappeared."

"Did they find him?" asked Martine, somewhat impatiently. Amy was to learn that Martine's temperament led her always to desire the climax almost before she had heard the story itself.

"Yes, they found him; for when they were some distance from shore they saw something that looked like a flag waving. A boat was sent out, and to the delight of those who went in it, they saw that the flag was a handkerchief tied to a hat on a stick, that the missing Aubrey was holding to attract their attention. Looking for his sword, the good priest had missed his way, and for seventeen days he had wandered in the woods, living on berries and roots."

"How delighted he must have been to see his friends!"

"Not more delighted than they to see him; for had he not been found, the consequences for the suspected Huguenots might have been serious."

"It is Yvonne's turn to tell us a story," said Martine, "but we all need to rest before tea, and I want to tell your mother about the quilts. If she disapproves of my buying so many—"

"I suppose that you will send them back;" Amy's tone contradicted her words.

"Oh, no; I will not send them back. But I do wonder what I shall do with them."

Yvonne and Martine went indoors, and Amy and Priscilla soon followed. Amy prepared her mother for Yvonne by telling her all that they had learned about the little girl.

"I won't discourage Martine's altruism," said Mrs. Redmond. "Her impulsiveness in the past has sometimes led her into trouble, but Martine herself will be benefited by having this warm interest in another. As to the quilts, though we cannot carry them about with us, they can be easily expressed home, and the duty will not be large."

After tea the whole party sat in the little parlor, to listen to Yvonne. Her first two or three songs were without accompaniment. They were plaintive songs with French words, and unfamiliar to the Americans who were listening. But a chance question revealed the fact that Yvonne was also familiar with much music that Amy knew well. Thereupon Martine suggested that if Amy would improvise some accompaniments Yvonne might be heard to even better advantage. So Amy, seated there at the melodeon, played, and Yvonne continued to sing, and some of the music was rendered with a dramatic power that surprised all who listened.

"Ah, she will be great some day," said the landlady, listening enraptured to the bird-like tones. "How it had pleased her poor mother to know that she was to be a singer!"

While Yvonne sang, various plans were rushing through Martine's busy brain. "Yvonne shall have a parlor organ, Yvonne shall have teachers, Yvonne shall have her eyes examined by a good oculist. Evidently she is not blind,—not really blind."

While she was thinking and planning, her eyes never left the face of the little French girl, held there by the wonderfully happy expression which lit it. Yvonne's wide, brown eyes, her half-parted lips, the little brown tendrils curling around her forehead, all combined to make a picture that impressed itself strongly on all in the room. Moreover, the gentle and unassuming manner of the young singer, as she received the praise showered on her, completely won the hearts of all. Or perhaps it would be more nearly true to say that if Priscilla's heart was not completely won, she at least had begun to see some reason in Martine's infatuation.

"Is it not wonderful?" asked Martine of Mrs. Redmond.

"She certainly sings remarkably well—for a little girl."

Martine looked up quickly at Mrs. Redmond. Was the latter able to find some flaw in what she herself considered altogether perfect? She had no time just then to question her, for Yvonne herself might overhear the reply, and besides, the young girl was about to sing again, and Martine could not spare a note.

When at last the tall figure of Alexandre Babet appeared in the doorway, they knew that the music must end, and with a protracted farewell from Martine, Yvonne and her adopted father started for home before nine o'clock.

"Yvonne did not seem as much overcome by the grandeur of the hotel as Alexandre prophesied," remarked Amy, as the girls went upstairs.

"Yvonne would never be overpowered by anything," responded Martine; "I don't believe she'd be surprised by the Auditorium."

Whereat both Amy and Priscilla laughed loudly. "To compare small things with great," said Priscilla, "of course she wouldn't be impressed by this hotel. Why, it's smaller than a summer boarding-house."

"I wonder what Alexandre meant?" mused Martine.

"Oh, it was only his way of trying to make you think that you were doing Yvonne a great favor by asking her here," responded Amy.

"Yes, the French way of pretending that things are what they are not," added Priscilla, as if the word "French" comprised the very essence of deceit.

"Take care," retorted Martine. "I never dared tell you before, but I had a French great-great-grandmother."

Although Priscilla made no reply to this, her inward comment was, "That accounts for many things that have made me wonder."

At breakfast the next morning, before Martine had come down to the table, Amy asked her mother what she really thought of Yvonne's singing.

"I do not profess to be a judge of that kind of thing, but the child seems to have a fine natural voice, as well as a musical nature. Yet, like all other singers, she must have her tones properly placed, and she is still too young to profit by expensive musical instruction. It is my own opinion that it would be better for her to sing little for the next few years. Some of the things that she sang last evening were beyond her, and there is danger of her forcing her voice, and so injuring it."

"Have you said this to Martine?"

"No, for Martine is the type of girl who profits most by finding out things for herself. She will learn gradually that everything cannot be done at once for Yvonne."

new people

"I don't like to."

"Why not?"

"It seems strange. They may not care to have us visit them."

"We can only try. If they turn us away why, that is the worst we need expect." So, drawing Priscilla's arm within hers, Amy led her up the narrow flagged walk toward the Convent School.

A sister wearing a glazed bonnet with a long veil was trimming rosebushes in the garden bed close to the house.

"Yes, surely, we are glad to have visitors. The school itself is closed now, for the girls have their holidays, but you can see all there is. Excuse me for a moment and I will be with you."

In a short time she had joined them in the little hallway to which they had been admitted by another sister.

"Would the ladies care to see the chapel?"

"Ladies" had a pleasant sound to Priscilla, and she put aside her prejudice against entering churches not of her own faith.

The chapel was simply a large room suitably fitted with altar and seats. It had no color, but everything was daintily white, with here and there a touch of gold.

The neat dormitory, the pleasant schoolroom, and the spotless cleanliness of the whole house appealed to Priscilla, and to her surprise she found herself asking the sister questions about her work.

"We are Sisters of Charity, and our headquarters are in Halifax," the good sister said gently. "The school is but a little part of our work. We go in and out among the sick and the troubled. The Acadians are good to their own, and no one need suffer here; but some will make mistakes, and some suffer through the fault of others, and often the priest and the sisters alone can set things right."

Soon they had seen all that there was to see, and when the sister, looking at the clock, regretted that she must leave them to visit a sick woman, both girls asked if they might not walk with her.

"With pleasure," she replied. "Indeed, I would take you to the house where I am going, were it not that this woman is too sick to see visitors."

"We should like to see another Acadian house," said Amy; "we have visited only that of Alexandre Babet, and that was so plain."

"Ah, you have been at Alexandre Babet's. Then you have seen the little Yvonne. Is she not charming?"

"Yes, charming and talented. We have heard her sing."

"Yvonne sings sweetly. We have taught her some music here, but nature has done the most for her, and she is so patient about her eyes."

"Do you think that she will be blind?" asked Amy, anxiously.

"Oh, no, not wholly blind, though it is largely a question of doctors. This came to her through an illness a few years ago. She did not have the right care. They did not understand. But there is always hope, and I think that she is no worse this year or two."

"We have a friend who has taken a great fancy to Yvonne. She preferred to go up to Alexandre Babet's this morning rather than to come sightseeing with us."

"Yvonne wins the heart of all so quickly, and her good father and mother, though adopted, would do everything for her if they could. Poor Alexandre looks for a gold-mine."