The Project Gutenberg EBook of Castles and Chateaux of Old Touraine and the Loire Country, by Francis Miltoun This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Castles and Chateaux of Old Touraine and the Loire Country Author: Francis Miltoun Illustrator: Blanche McManus Release Date: August 25, 2011 [EBook #37211] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CASTLES, CHATEAUX OF OLD TOURAINE *** Produced by Elizaveta Shevyakhova, Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Rambles on the Riviera

Rambles in Normandy

Rambles in Brittany

The Cathedrals and Churches of the Rhine

The Cathedrals of Northern France

The Cathedrals of Southern France

The Cathedrals of Italy (In preparation)

This book is not the result of ordinary conventional rambles, of sightseeing by day, and flying by night, but rather of leisurely wanderings, for a somewhat extended period, along the banks of the Loire and its tributaries and through the countryside dotted with those splendid monuments of Renaissance architecture which have perhaps a more appealing interest for strangers than any other similar edifices wherever found.

Before this book was projected, the conventional tour of the château country had been "done," Baedeker, Joanne and James's "Little Tour" in hand. On another occasion Angers, with its almost inconceivably real castellated fortress, and Nantes, with its memories of the "Edict" and "La Duchesse Anne," had been tasted and digested en route to a certain little artist's village in Brittany.

On another occasion, when we were headed due south, we lingered for a time in the uppervi valley, between "the little Italian city of Nevers" and "the most picturesque spot in the world"—Le Puy.

But all this left certain ground to be covered, and certain gaps to be filled, though the author's note-books were numerous and full to overflowing with much comment, and the artist's portfolio was already bulging with its contents.

So more note-books were bought, and, following the genial Mark Twain's advice, another fountain pen and more crayons and sketch-books, and the author and artist set out in the beginning of a warm September to fill those gaps and to reduce, if possible, that series of rambles along the now flat and now rolling banks of the broad blue Loire to something like consecutiveness and uniformity; with what result the reader may judge.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| By Way of Introduction | v | |

| I. | A General Survey | 1 |

| II. | The Orléannais | 30 |

| III. | The Blaisois and the Sologne | 56 |

| IV. | Chambord | 94 |

| V. | Cheverny, Beauregard, and Chaumont | 110 |

| VI. | Touraine: The Garden Spot of France | 128 |

| VII. | Amboise | 148 |

| VIII. | Chenonceaux | 171 |

| IX. | Loches | 188 |

| X. | Tours and About There | 203 |

| XI. | Luynes and Langeais | 221 |

| XII. | Azay-le-Rideau, Ussé, and Chinon | 241 |

| XIII. | Anjou and Bretagne | 273 |

| XIV. | South of the Loire | 301 |

| XV. | Berry and George Sand's Country | 313 |

| XVI. | The Upper Loire | 330 |

| Index | 337 |

| PAGE | ||

| A Peasant Girl of Touraine | Frontispiece | |

| Itinerary of the Loire (Map) | 1 | |

| A Lace-maker of the Upper Loire | 5 | |

| The Loire Châteaux (Map) | 9 | |

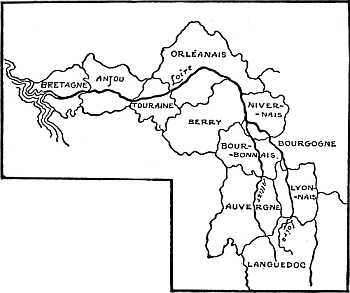

| The Ancient Provinces of the Loire Valley and Their Capitals (Map) | 15 | |

| The Loire near la Charité | 19 | |

| Coiffes of Amboise and Orléans | 21 | |

| The Châteaux of the Loire (Map) | 31 | |

| Environs of Orléans (Map) | 39 | |

| The Loiret | 42 | |

| The Loire at Meung | 46 | |

| Beaugency | 51 | |

| Arms of the City of Blois | 58 | |

| The Riverside at Blois | 59 | |

| Signature of François Premier | 60 | |

| Cypher of Anne de Bretagne, at Blois | 62 | |

| Arms of Louis XII. | 65 | |

| Central Doorway, Château de Blois | 67 | |

| The Châteaux of Blois (Diagram) | 69 | |

| Cypher of François Premier and Claude of France, at Blois | 72 | |

| Native Types in the Sologne | 89 | |

| Donjon of Montrichard | 92 | |

| Arms of François Premier, at Chambord | 99 | |

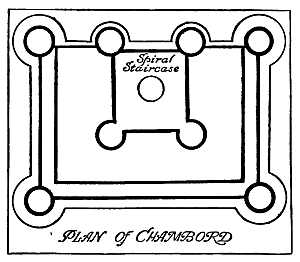

| Plan of Château de Chambord | 103 | |

| xChâteau de Chambord | 105 | |

| Château de Cheverny | 110 | |

| Cheverny-sur-Loire | 113 | |

| Chaumont | 116 | |

| Signature of Diane de Poitiers | 118 | |

| The Loire in Touraine | 134 | |

| The Vintage in Touraine | 142 | |

| Château d'Amboise | 148 | |

| Sculpture from the Chapelle de St. Hubert | 165 | |

| Cypher of Anne de Bretagne, Hôtel de Ville, Amboise | 168 | |

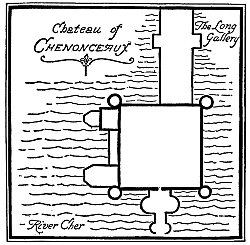

| Château de Chenonceaux | 178 | |

| Château de Chenonceaux (Diagram) | 179 | |

| Loches | 189 | |

| Loches and Its Church | 192 | |

| Sketch Plan of Loches | 198 | |

| St. Ours, Loches | 199 | |

| Tours | 202 | |

| Arms of the Printers, Avocats, and Innkeepers, Tours | 205 | |

| Scene in the Quartier de la Cathédrale, Tours | 208 | |

| Plessis-les-Tours in the Time of Louis XI. | 213 | |

| Environs of Tours (Map) | 219 | |

| A Vineyard of Vouvray | 223 | |

| Mediæval Stairway and the Château de Luynes | 224 | |

| Ruins of Cinq-Mars | 229 | |

| Château de Langeais | 233 | |

| Arms of Louis XII. and Anne de Bretagne | 237 | |

| Château d'Azay-le-Rideau | 244 | |

| Château d'Ussé | 249 | |

| The Roof-tops of Chinon | 253 | |

| Rabelais | 256 | |

| Château de Chinon | 259 | |

| Cuisines, Fontevrault | 265 | |

| xiChâteau de Saumur | 277 | |

| The Ponts de Cé | 284 | |

| Château d'Angers | 289 | |

| Environs of Nantes (Map) | 297 | |

| Donjon of the Château de Clisson | 307 | |

| Berry (Map) | 313 | |

| La Tour, Sancerre | 317 | |

| Château de Gien | 318 | |

| Château de Valençay | 322 | |

| Gateway of Mehun-sur-Yevre | 324 | |

| Le Carrior Doré, Romorantin | 326 | |

| Église S. Aignan, Cosne | 331 | |

| Pouilly-sur-Loire | 332 | |

| Porte du Croux, Nevers | 335 |

Any account of the Loire and of the towns along its banks must naturally have for its chief mention Touraine and the long line of splendid feudal and Renaissance châteaux which reflect themselves so gloriously in its current.

The Loire possesses a certain fascination and charm which many other more commercially great rivers entirely lack, and, while the element of absolute novelty cannot perforce be claimed for it, it has the merit of appealing largely to the lover of the romantic and the picturesque.2

A French writer of a hundred years ago dedicated his work on Touraine to "Le Baron de Langeais, le Vicomte de Beaumont, le Marquis de Beauregard, le Comte de Fontenailles, le Comte de Jouffroy-Gonsans, le Duc de Luynes, le Comte de Vouvray, le Comte de Villeneuve, et als.;" and he might have continued with a directory of all the descendants of the noblesse of an earlier age, for he afterward grouped them under the general category of "Propriétaires des fortresses et châteaux les plus remarquables—au point de vue historique ou architectural."

He was fortunate in being able, as he said, to have had access to their "papiers de famille," their souvenirs, and to have been able to interrogate them in person.

Most of his facts and his gossip concerning the personalities of the later generations of those who inhabited these magnificent establishments have come down to us through later writers, and it is fortunate that this should be the case, since the present-day aspect of the châteaux is ever changing, and one who views them to-day is chagrined when he discovers, for instance, that an iron-trussed, red-tiled wash-house has been built on the banks of the Cosson before the magnificent château of3 Chambord, and that somewhere within the confines of the old castle at Loches a shopkeeper has hung out his shingle, announcing a newly discovered dungeon in his own basement, accidentally come upon when digging a well.

Balzac, Rabelais, and Descartes are the leading literary celebrities of Tours, and Balzac's "Le Lys dans la Vallée" will give one a more delightful insight into the old life of the Tourangeaux than whole series of guide-books and shelves of dry histories.

Blois and its counts, Tours and its bishops, and Amboise and its kings, to say nothing of Fontevrault, redolent of memories of the Plantagenets, Nantes and its famous "Edict," and its equally infamous "Revocation," have left vivid impress upon all students of French history. Others will perhaps remember Nantes for Dumas's brilliant descriptions of the outcome of the Breton conspiracy.

All of us have a natural desire to know more of historic ground, and whether we make a start by entering the valley of the Loire at the luxurious midway city of Tours, and follow the river first to the sea and then to the source, or make the journey from source to mouth, or vice versa, it does not matter in the least. We traverse the same ground and we meet the4 same varying conditions as we advance a hundred kilometres in either direction.

Tours, for example, stands for all that is typical of the sunny south. Prune and palm trees thrust themselves forward in strong contrast to the cider-apples of the lower Seine. Below Tours one is almost at the coast, and the tables d'hôte are abundantly supplied with sea-food of all sorts. Above Tours the Orléannais is typical of a certain well-to-do, matter-of-fact existence, neither very luxurious nor very difficult.

Nevers is another step and resembles somewhat the opulence of Burgundy as to conditions of life, though the general aspect of the city, as well as a great part of its history, is Italian through and through.

The last great step begins at Le Puy, in the great volcanic Massif Centrale, where conditions of life, if prosperous, are at least harder than elsewhere.

Such are the varying characteristics of the towns and cities through which the Loire flows. They run the whole gamut from gay to earnest and solemn; from the ease and comfort of the country around Tours, almost sub-tropical in its softness, to the grime and smoke of busy5 St. Etienne, and the chilliness and rigours of a mountain winter at Le Puy.

These districts are all very full of memories of events which have helped to build up the solidarity of France of to-day, though the Nantois still proudly proclaims himself a Breton, and the Tourangeau will tell you that his is the tongue, above all others, which speaks the purest French,—and so on through the whole category, each and every citizen of a petit pays living up to his traditions to the fullest extent possible.

In no other journey in France, of a similar length, will one see as many varying contrasts in conditions of life as he will along the length of the Loire, the broad, shallow river which St. Martin, Charles Martel, and Louis XI., the typical figures of church, arms, and state, came to know so well.

Du Bellay, a poet of the Renaissance, has sung the praises of the Loire in a manner unapproached by any other topographical poet, if one may so call him, for that is what he really was in this particular instance.

There is a great deal of patriotism in it all, too, and certainly no sweet singer of the present day has even approached these lines,6 which are eulogistic without being fulsome and fervent without being lurid.

The verses have frequently been rendered into English, but the following is as good as any, and better than most translations, though it is one of those fragments of "newspaper verse" whose authors are lost in obscurity.

In history the Loire valley is rich indeed, from the days of the ancient Counts of Touraine to those of Mazarin, who held forth at Nevers. Touraine has well been called the heart of the old French monarchy.

Provincial France has a charm never known to Paris-dwellers. Balzac and Flaubert were provincials, and Dumas was a city-dweller,—and there lies the difference between them.

Balzac has written most charmingly of Touraine in many of his books, in "Le Lys dans la Vallée" and "Le Curé de Tours" in particular; not always in complimentary terms,7 either, for he has said that the Tourangeaux will not even inconvenience themselves to go in search of pleasure. This does not bespeak indolence so much as philosophy, so most of us will not cavil. George Sand's country lies a little to the southward of Touraine, and Berry, too, as the authoress herself has said, has a climate "souple et chaud, avec pluie abondant et courte."

The architectural remains in the Loire valley are exceedingly rich and varied. The feudal system is illustrated at its best in the great walled château at Angers, the still inhabited and less grand château at Langeais, the ruins at Cinq-Mars, and the very scanty remains of Plessis-les-Tours.

The ecclesiastical remains are quite as great. The churches are, many of them, of the first rank, and the great cathedrals at Nantes, Angers, Tours, and Orléans are magnificent examples of the church-builders' art in the middle ages, and are entitled to rank among the great cathedrals, if not actually of the first class.

With modern civic and other public buildings, the case is not far different. Tours has a gorgeous Hôtel de Ville, its architecture being of the most luxuriant of modern French8 Renaissance, while the railway stations, even, at both Tours and Orléans, are models of what railway stations should be, and in addition are decoratively beautiful in their appointments and arrangements,—which most railway stations are not.

Altogether, throughout the Loire valley there is an air of prosperity which in a more vigorous climate is often lacking. This in spite of the alleged tendency in what is commonly known as a relaxing climate toward laisser-aller.

Finally, the picturesque landscape of the Loire is something quite different from the harder, grayer outlines of the north. All is of the south, warm and ruddy, and the wooded banks not only refine the crudities of a flat shore-line, but form a screen or barrier to the flowering charms of the examples of Renaissance architecture which, in Touraine, at least, are as thick as leaves in Vallambrosa.

Starting at Gien, the valley of the Loire begins to offer those monumental châteaux which have made its fame as the land of castles. From the old fortress-château of Gien to the Château de Clisson, or the Logis de la Duchesse Anne at Nantes, is one long succession of florid masterpieces, not to be equalled elsewhere.9

The true château region of Touraine—by which most people usually comprehend the Loire châteaux—commences only at Blois. Here the edifices, to a great extent, take on these superfine residential attributes which were the glory of the Renaissance period of French architecture.

Both above and below Touraine, at Montrichard, at Loches, and Beaugency, are still to be found scattering examples of feudal fortresses and donjons which are as representative of their class as are the best Norman structures of the same era, the great fortresses of Arques, Falaise, Domfront, and Les Andelys being usually accounted as the types which gave the stimulus to similar edifices elsewhere.

In this same versatile region also, beginning10 perhaps with the Orléannais, are a vast number of religious monuments equally celebrated. For instance, the church of St. Benoit-sur-Loire is one of the most important Romanesque churches in all France, and the cathedral of St. Gatien, with its "bejewelled façade," at Tours, the twin-spired St. Maurice at Angers, and even the pompous, and not very good Gothic, edifice at Orléans (especially noteworthy because its crypt is an ancient work anterior to the Capetian dynasty) are all wonderfully interesting and imposing examples of mediæval ecclesiastical architecture.

Three great tributaries enter the Loire below Tours, the Cher, the Indre, and the Vienne. The first has for its chief attractions the Renaissance châteaux St. Aignan and Chenonceaux, the Roman remains of Chabris, Thézée, and Larçay, the Romanesque churches of Selles and St. Aignan, and the feudal donjon of Montrichard. The Indre possesses the château of Azay-le-Rideau and the sombre fortresses of Montbazon and Loches; while the Vienne depends for its chief interest upon the galaxy of fortress-châteaux at Chinon.

The Loire is a mighty river and is navigable for nearly nine hundred kilometres of its length, almost to Le Puy, or, to be exact, to11 the little town of Vorey in the Department of the Haute Loire.

At Orléans, Blois, or Tours one hardly realizes this, much less at Nevers. The river appears to be a great, tranquil, docile stream, with scarce enough water in its bed to make a respectable current, leaving its beds and bars of sable and cailloux bare to the sky.

The scarcity of water, except at occasional flood, is the principal and obvious reason for the absence of water-borne traffic, even though a paternal ministerial department of the government calls the river navigable.

At the times of the grandes crues there are four metres or more registered on the big scale at the Pont d'Ancenis, while at other times it falls to less than a metre, and when it does there is a mere rivulet of water which trickles through the broad river-bottom at Chaumont, or Blois, or Orléans. Below Ancenis navigation is not so difficult, but the current is more strong.

From Blois to Angers, on the right bank, extends a long dike which carries the roadway beside the river for a couple of hundred kilometres. This is one of the charms of travel by the Loire. The only thing usually seen on the bosom of the river, save an occasional fish12ing punt, is one of those great flat-bottomed ferry-boats, with a square sail hung on a yard amidships, such as Turner always made an accompaniment to his Loire pictures, for conditions of traffic on the river have not greatly changed.

Whenever one sees a barge or a boat worthy of classification with those one finds on the rivers of the east or north, or on the great canals, it is only about a quarter of the usual size; so, in spite of its great navigable length, the waterway of the Loire is to be considered more as a picturesque and healthful element of the landscape than as a commercial proposition.

Where the great canals join the river at Orléans, and from Chatillon to Roanne, the traffic increases, though more is carried by the canal-boats on the Canal Latéral than by the barges on the Loire.

It is only on the Loire between Angers and Nantes that there is any semblance of river traffic such as one sees on most of the other great waterways of Europe. There is a considerable traffic, too, which descends the Maine, particularly from Angers downward, for Angers with its Italian skies is usually thought of, and really is to be considered, as a Loire13 town, though it is actually on the banks of the Maine some miles from the Loire itself.

One thousand or more bateaux make the ascent to Angers from the Loire at La Pointe each year, all laden with a miscellaneous cargo of merchandise. The Sarthe and the Loir also bring a notable agricultural traffic to the greater Loire, and the smaller confluents, the Dive, the Thouet, the Authion, and the Layon, all go to swell the parent stream until, when it reaches Nantes, the Loire has at last taken on something of the aspect of a well-ordered and useful stream, characteristics which above Nantes are painfully lacking. Because of its lack of commerce the Loire is in a certain way the most noble, magnificent, and aristocratic river of France; and so, too, it is also in respect to its associations of the past.

It has not the grandeur of the Rhône when the spring freshets from the Jura and the Swiss lakes have filled it to its banks; it has not the burning activity of the Seine as it bears its thousands of boat-loads of produce and merchandise to and from the Paris market; it has not the prettiness of the Thames, nor the legendary aspect of the Rhine; but in a way it combines something of the features of all, and has, in addition, a tone that is all its14 own, as it sweeps along through its countless miles of ample curves, and holds within its embrace all that is best of mediæval and Renaissance France, the period which built up the later monarchy and, who shall not say, the present prosperous republic.

Throughout most of the river's course, one sees, stretching to the horizon, row upon row of staked vineyards with fruit and leaves in luxuriant abundance and of all rainbow colours. The peasant here, the worker in the vineyards, is a picturesque element. He is not particularly brilliant in colouring, but he is usually joyous, and he invariably lives in a well-kept and brilliantly environed habitation and has an air of content and prosperity amid the well-beloved treasures of his household.

The Loire is essentially a river of other days. Truly, as Mr. James has said, "It is the very model of a generous, beneficent stream ... a wide river which you may follow by a wide road is excellent company."

The Frenchman himself is more flowery: "C'est la plus noble rivière de France. Son domaine est immense et magnifique."

|

|

The Loire is the longest river in France, and the only one of the four great rivers whose basin or watershed lies wholly within French16 territory. It moreover traverses eleven provinces. It rises in a fissure of granite rock at the foot of the Gerbier-de-Jonc, a volcanic cone in the mountains of the Vivarais, a hundred kilometres or more south of Lyons. In three kilometres, approximately two miles, the little torrent drops a thousand feet, after receiving to its arms a tiny affluent coming from the Croix de Monteuse.

For twelve kilometres the river twists and turns around the base of the Vivarais mountains, and finally enters a gorge between the rocks, and mingles with the waters of the little Lac d'Issarles, entering for the first time a flat lowland plain like that through which its course mostly runs.

The monument-crowned pinnacles of Le Puy and the inverted bowl of Puy-de-Dôme rise high above the plain and point the way to Roanne, where such activity as does actually take place upon the Loire begins.

Navigation, classed officially as "flottable," merely, has already begun at Vorey, just below Le Puy, but the traffic is insignificant.

Meantime the streams coming from the direction of St. Etienne and Lyons have been added to the Loire, but they do not much increase its bulk. St. Galmier, the source dear17 to patrons of tables d'hôte on account of its palatable mineral water, which is about the only decent drinking-water one can buy at a reasonable price, lies but a short distance away to the right.

At St. Rambert the plain of Forez is entered, and here the stream is enriched by numberless rivulets which make their way from various sources through a thickly wooded country.

From Roanne onward, the Canal Latéral keeps company with the Loire to Chatillon, not far from Orléans.

Before reaching Nevers, the Canal du Nivernais branches off to the left and joins the Loire with the Yonne at Auxerre. Daudet tells of the life of the Canal du Nivernais, in "La Belle Nivernaise," in a manner too convincingly graphic for any one else to attempt the task, in fiction or out of it. Like the Tartarin books, "La Belle Nivernaise" is distinctly local, and forms of itself an excellent guide to a little known and little visited region.

At Nevers the topography changes, or rather, the characteristics of the life of the country round about change, for the topography, so far as its profile is concerned, remains much the same for three-fourths the length of this great river. Nevers, La Charité,18 Sancerre, Gien, and Cosne follow in quick succession, all reminders of a historic past as vivid as it was varied.

From the heights of Sancerre one sees a wonderful history-making panorama before him. Cæsar crossed the Loire at Gien, the Franks forded the river at La Charité, when they first went against Aquitaine, and Charles the Bald came sadly to grief on a certain occasion at Pouilly.

It is here that the Loire rises to its greatest flood, and hundreds of times, so history tells, from 490 to 1866, the fickle river has caused a devastation so great and terrible that the memory of it is not yet dead.

This hardly seems possible of this usually tranquil stream, and there have always been scoffers.

Madame de Sévigné wrote in 1675 to M. de Coulanges (but in her case perhaps it was mere well-wishing), "La belle Loire, elle est un peu sujette à se déborder, mais elle en est plus douce."

Ancient writers were wont to consider the inundations of the Loire as a punishment from Heaven, and even in later times the superstition—if it was a superstition—still remained.

In 1825, when thousands of charcoal-burners19 (charbonniers) were all but ruined, they petitioned the government for assistance. The official who had the matter in charge, and whose name—fortunately for his fame—does not appear to have been recorded, replied simply that the flood was a periodical condition of affairs which the Almighty brought about as occasion demanded, with good cause, and for this reason he refused all assistance.

Important public works have done much to prevent repetitions of these inundations, but the danger still exists, and always, in a wet season, there are those dwellers along the river's banks who fear the rising flood as they would the plague.

Chatillon, with its towers; Gien, a busy hive of industry, though with a historic past; Sully; and St. Benoit-sur-Loire, with its unique double transepted church; all pass in rapid review, and one enters the ancient capital of the Orléannais quite ready for the new chapter which, in colouring, is to be so different from that devoted to the upper valley.

From Orléans, south, one passes through a veritable wonderland of fascinating charms. Châteaux, monasteries, and great civic and ecclesiastical monuments pass quickly in turn.

Then comes Touraine which all love, the20 river meantime having grown no more swift or ample, nor any more sluggish or attenuated. It is simply the same characteristic flow which one has known before.

The landscape only is changing, while the fruits and flowers, and the trees and foliage are more luxuriant, and the great châteaux are more numerous, splendid, and imposing.

Of his well-beloved Touraine, Balzac wrote: "Do not ask me why I love Touraine; I love it not merely as one loves the cradle of his birth, nor as one loves an oasis in a desert, but as an artist loves his art."

Blois, with its bloody memories; Chaumont, splendid and retired; Chambord, magnificent, pompous, and bare; Amboise, with its great tower high above the river, follow in turn till the Loire makes its regal entrée into Tours. "What a spectacle it is," wrote Sterne in "Tristram Shandy," "for a traveller who journeys through Touraine at the time of the vintage."

And then comes the final step which brings the traveller to where the limpid waters of the Loire mingle with the salty ocean, and what a triumphant meeting it is!

Most of the cities of the Loire possess but one bridge, but Tours has three, and, as be21comes a great provincial capital, sits enthroned upon the river-bank in mighty splendour.

The feudal towers of the Château de Luynes are almost opposite, and Cinq-Mars, with its pagan "pile" and the ruins of its feudal castle high upon a hill, points the way down-stream like a mariner's beacon. Langeais follows, and the Indre, the Cher, and the Vienne, all ample and historic rivers, go to swell the flood which passes under the bridges of Saumur, Ancenis, and Ponts de Cé.

From Tours to the ocean, the Loire comes to its greatest amplitude, though even then, in spite of its breadth, it is, for the greater part of the year, impotent as to the functions of a great river.

Below Angers the Loire receives its first great affluent coming from the country lying back of the right bank: the Maine itself is a considerable river. It rises far up in the Breton peninsula, and before it empties itself into the Loire, it has been aggrandized by three great tributaries, the Loir, the Sarthe, and the Mayenne.

Here in this backwater of the Loire, as one might call it, is as wonderful a collection of natural beauties and historical châteaux as on the Loire itself. Châteaudun, Mayenne, and22 Vendôme are historic ground of superlative interest, and the great castle at Châteaudun is as magnificent in its way as any of the monuments of the Loire. Vendôme has a Hôtel de Ville which is an admirable relic of a feudal edifice, and the clocher of its church, which dominates many square leagues of country, is counted as one of the most perfectly disposed church spires in existence, as lovely, almost, as Texier's masterwork at Chartres, or the needle-like flêches at Strasburg or Freiburg in Breisgau.

The Maine joins the Loire just below Angers, at a little village significantly called La Pointe. Below La Pointe are St. Georges-sur-Loire, and three châteaux de commerce which give their names to the three principal Angevin vineyards: Château Serrand, l'Epinay, and Chevigné.

Vineyard after vineyard, and château after château follow rapidly, until one reaches the Ponts de Cé with their petite ville,—all very delightful. Not so the bridge at Ancenis, where the flow of water is marked daily on a huge black and white scale. The bridge is quite the ugliest wire-rope affair to be seen on the Loire, and one is only too glad to leave it behind,23 though it is with a real regret that he parts from Ancenis itself.

Some years ago one could go from Angers to St. Nazaire by boat. It must have been a magnificent trip, extraordinarily calm and serene, amid an abundance of picturesque details; old châteaux and bridges in strong contrast to the prairies of Touraine and the Orléannais. One embarked at the foot of the stupendously towered château of King René, and for a petite heure navigated the Maine in the midst of great chalands, fussy little remorqueurs and barques until La Pointe was reached, when the Loire was followed to Nantes and St. Nazaire.

To-day this fine trip is denied one, the boats going only so far as La Pointe.

Below Angers the Loire flows around and about a veritable archipelago of islands and islets, cultivated with all the luxuriance of a back-yard garden, and dotted with tiny hamlets of folk who are supremely happy and content with their lot.

Some currents which run behind the islands are swift flowing and impetuous, while others are practically elongated lakes, as dead as those lômes which in certain places flank the Saône and the Rhône.24

All these various branches are united as the Loire flows between the piers of the ungainly bridge of the Chemin-de-fer de Niort as it crosses the river at Chalonnes.

Champtocé and Montjean follow, each with an individuality all its own. Here the commerce takes on an increased activity, thanks to the great national waterway known as the "Canal de Brest à Nantes." Here at the busy port of Montjean—which the Angevins still spell and pronounce Montéjean—the Loire takes on a breadth and grandeur similar to the great rivers in the western part of America. Montjean is dominated by a fine ogival church, with a battery of arcs-boutants which are a joy in themselves.

On the other bank, lying back of a great plain, which stretches away from the river itself, is Champtocé, pleasantly situated on the flank of a hill and dominated by the ruins of a thirteenth-century château which belonged to the cruel Gilles de Retz, somewhat apocryphally known to history as "Barbe-bleu"—not the Bluebeard of the nursery tale, who was of Eastern origin, but a sort of Occidental successor who was equally cruel and bloodthirsty in his attitude toward his whilom wives.

From this point on one comes within the25 sphere of influence of Nantes, and there is more or less of a suburban traffic on the railway, and the plodders cityward by road are more numerous than the mere vagabonds of the countryside.

The peasant women whom one meets wear a curious bonnet, set on the head well to the fore, with wings at the side folded back quite like the pictures that one sees of the mediæval dames of these parts, a survival indeed of the middle ages.

The Loire becomes more and more animated and occasionally there is a great tow of boats like those that one sees continually passing on the lower Seine. Here the course of the Loire takes on a singular aspect. It is filled with long flat islands, sometimes in archipelagos, but often only a great flat prairie surrounded by a tranquil canal, wide and deep, and with little resemblance to the mistress Loire of a hundred or two kilometres up-stream. All these isles are in a high state of cultivation, though wholly worked with the hoe and the spade, both of them of a primitiveness that might have come down from Bible times; rare it is to see a horse or a harrow on these "bouquets of verdure surrounded by waves."

Near Oudon is one of those monumental26 follies which one comes across now and then in most foreign countries: a great edifice which serves no useful purpose, and which, were it not for certain redeeming features, would be a sorry thing indeed. The "Folie-Siffait," a citadel which perches itself high upon the summit of a hill, was—and is—an amusette built by a public-spirited man of Nantes in order that his workmen might have something to do in a time of a scarcity of work. It is a bizarre, incredible thing, but the motive which inspired its erection was most worthy, and the roadway running beneath, piercing its foundation walls, gives a theatrical effect which, in a way, makes it the picturesque rival of many a more famous Rhine castle.

The river valley widens out here at Oudon, practically the frontier of Bretagne and Anjou. The railroad pierces the rock walls of the river with numerous tunnels along the right bank, and the Vendean country stretches far to the southward in long rolling hills quite unlike any of the characteristics of other parts of the valley. Finally, the vast plain of Mauves comes into sight, beautifully coloured with a white and iron-stained rocky background which is startlingly picturesque in its way, if not27 wholly beautiful according to the majority of standards.

Next comes what a Frenchman has called a "tumultuous vision of Nantes." To-day the very ancient and historic city which grew up from the Portus Namnetum and the Condivicnum of the Romans is indeed a veritable tumult of chimneys, masts, and locomotives. But all this will not detract one jot from its reputation of being one of the most delightful of provincial capitals, and the smoke and activity of its port only tend to accentuate a note of colour that in the whole itinerary of the Loire has been but pale.

Below Nantes the Loire estuary has turned the surrounding country into a little Holland, where fisherfolk and their boats, with sails of red and blue, form charming symphonies of pale colour. In the cabarets along its shores there is a strange medley of peasants, sea-farers, and fisher men and women. Not so cosmopolitan a crew as one sees in the harbourside cabarets at Marseilles, or even Le Havre, but sufficiently strange to be a fascination to one who has just come down from the headwaters.

The "Section Maritime," from Nantes to the sea, is a matter of some sixty kilometres.28 Here the boats increase in number and size. They are known as gabares, chalands, and alléges, and go down with the river-current and return on the incoming ebb, for here the river is tidal.

Gray and green is the aspect at the Loire's source, and green and gray it still is, though of a decidedly different colour-value, at St. Nazaire, below Nantes, the real deep-water port of the Loire.

By this time the river has amplified into a broad estuary which is lost in the incoming and outgoing tides of the Bay of Biscay.

For nearly a thousand kilometres the Loire has wound its way gently and broadly through rocky escarpments, fertile plains, populous and luxurious towns,—all of it historic ground,—by stately châteaux and through vineyards and fruit orchards, with a placid grandeur.

Now it becomes more or less prosaic and matter-of-fact, though in a way no less interesting, as it takes on some of the attributes of the outside world.

This outline, then, approximates somewhat a portrait of the Loire. It is the result of many pilgrimages enthusiastically undertaken; a long contemplation of the charms of perhaps29 the most beautiful river in France, from its source to its mouth, at all seasons of the year.

The riches and curios of the cities along its banks have been contemplated with pleasure, intermingled with a memory of many stirring scenes of the past, but it is its châteaux that make it famous.

The story of the châteaux has been told before in hundreds of volumes, but only a personal view of them will bring home to one the manners and customs of one of the most luxurious periods of life in the France of other days.30

Of the many travelled English and Americans who go to Paris, how few visit the Loire valley with its glorious array of mediæval and Renaissance châteaux. No part of France, except Paris, is so accessible, and none is so comfortably travelled, whether by road or by rail.

At Orleans one is at the very gateway of this splendid, bountiful region, the lower valley of the Loire. Here the river first takes on a complexion which previously it had lacked, for it is only when the Loire becomes the boundary-line between the north and the south that one comes to realize its full importance.

The Orléannais, like many another province of mid-France, is a region where plenty awaits rich and poor alike. Not wholly given over to agriculture, nor yet wholly to manufacturing, it is without that restless activity of the31 frankly industrial centres of the north. In spite of this, though, the Orléannais is not idle.

Orleans is the obvious pointe de départ for all the wonderland of the Renaissance which is to follow, but itself and its immediate surroundings have not the importance for the visitor, in spite of the vivid historical chapters which have been written here in the past, that many another less famous city possesses. By this is meant that the existing monuments of history are by no means as numerous or splendid here as one might suppose. Not that they are entirely lacking, but rather that they are of a different species altogether from that array of magnificently planned châteaux which line the banks of the Loire below.

To one coming from the north the entrance to the Orléannais will be emphatically marked. It is the first experience of an atmosphere which, if not characteristically or climatically of the south, is at least reminiscent thereof, with a luminosity which the provinces of old France farther north entirely lack.

As Lavedan, the Académicien, says: "Here all focuses itself into one great picture, the combined romance of an epoch. Have you not been struck with a land where the clouds, the32 atmosphere, the odour of the soil, and the breezes from afar, all comport, one with another, in true and just proportions?" This is the Orléannais, a land where was witnessed the morning of the Valois, the full noon of Louis XIV., and the twilight of Louis XVI.

The Orléannais formed a distinct part of mediæval France, as it did, ages before, of western Gaul. Of all the provinces through which the Loire flows, the Orléannais is as prolific as any of great names and greater events, and its historical monuments, if not so splendid as those in Touraine, are no less rare.

Orleans itself contains many remarkable Gothic and Renaissance constructions, and not far away is the ancient church of the old abbey of Notre Dame de Cléry, one of the most historic and celebrated shrines in the time of the superstitious Louis XI.; while innumerable mediæval villes and ruined fortresses plentifully besprinkle the province.

One characteristic possessed by the Orléannais differentiates it from the other outlying provinces of the old monarchy. The people and the manners and customs of this great and important duchy were allied, in nearly all things, with the interests and events of the capital itself, and so there was always a lack33 of individuality, which even to-day is noticeably apparent in the Orleans capital. The shops, hotels, cafés, and the people themselves might well be one of the quartiers of Paris, so like are they in general aspect.

The notable Parisian character of the inhabitants of Orleans, and the resemblance of the people of the surrounding country to those of the Ile of France, is due principally to the fact that the Orléannais was never so isolated as many others of the ancient provinces. It was virtually a neighbour of the capital, and its relations with it were intimate and numerous. Moreover, it was favoured by a great number of lines of communication by road and by water, so that its manners and customs became, more or less unconsciously, interpolations.

The great event of the year in Orleans is the Fête de Jeanne d'Arc, which takes place in the month of May. Usually few English and American visitors are present, though why it is hard to reason out, for it takes place at quite the most delightful season in the year. Perhaps it is because Anglo-Saxons are ashamed of the part played by their ancestors in the shocking death of the maid of Domremy and Orleans. Innumerable are the relics and reminders of the "Maid" scattered through34out the town, and the local booksellers have likewise innumerable and authoritative accounts of the various episodes of her life, which saves the necessity of making further mention here.

There are several statues of Jeanne d'Arc in the city, and they have given rise to the following account written by Jules Lemaitre, the Académicien:

"I believe that the history of Jeanne d'Arc was the first that was ever told to me (before even the fairy-tales of Perrault). The 'Mort de Jeanne d'Arc,' of Casimir Delavigne, was the first fable that I learned, and the equestrian statue of the 'Maid,' in the Place Martroi, at Orleans, is perhaps the oldest vision that my memory guards.

"This statue of Jeanne d'Arc is absurd. She has a Grecian profile, and a charger which is not a war-horse but a race-horse. Nevertheless to me it was noble and imposing.

"In the courtyard of the Hôtel de Ville is a petite pucelle, very gentle and pious, who holds against her heart her sword, after the manner of a crucifix. At the end of the bridge across the Loire is another Jeanne d'Arc, as the maid of war, surrounded by swirling draperies, as in a picture of Juvenet's. This to me tells the35 whole story of the reverence with which the martyred 'Maid' is regarded in the city of Orleans by the Loire."

One can appreciate all this, and to the full, for a Frenchman is a stern critic of art, even that of his own countrymen, and Jeanne d'Arc, along with some other celebrities, is one of those historical figures which have seldom had justice done them in sculptured or pictorial representations. The best, perhaps, is the precocious Lepage's fine painting, now in America. What would not the French give for the return of this work of art?

The Orléannais, with the Ile de France, formed the particular domain of the third race of French monarchs. From 1364 to 1498 the province was an appanage known as the Duché d'Orleans, but it was united with the Crown by Louis XII., and finally divided into the Departments of Loir et Cher, Eure et Loir, and Loiret.

Like the "pardons" and "benedictions" of Finistère and other parts of Bretagne, the peasants of the Loiret have a quaint custom which bespeaks a long handed-down superstition. On the first Sunday of Lent they hie themselves to the fields with lighted fagots and chanting the following lines:36

Just how far the curé endorses these sentiments, the author of this book does not know. The explanation of the rather extraordinary proceeding came from one of the participants, who, having played his part in the ceremony, dictated the above lines over sundry petits verres paid for by the writer. The day is not wound up, however, with an orgy of eating and drinking, as is sometimes the case in far-western Brittany. The peasant of the Loiret simply eats rather heavily of "mi," which is nothing more or less than oatmeal porridge, after which he goes to bed.

The Loire rolls down through the Orléannais, from Châteauneuf-sur-Loire and Jargeau, and cuts the banks of sable, and the very shores themselves, into little capes and bays which are delightful in their eccentricity. Here cuts in the Canal d'Orleans, which makes possible the little traffic that goes on between the Seine and the Loire.

A few kilometres away from the right bank of the Loire, in the heart of the Gatanais, is37 Lorris, the home of Guillaume de Lorris, the first author of the "Roman de la Rose." For this reason alone it should become a literary shrine of the very first rank, though, in spite of its claim, no one ever heard of a literary pilgrim making his way there.

Lorris is simply a big, overgrown French market-town, which is delightful enough in its somnolence, but which lacks most of the attributes which tourists in general seem to demand.

At Lorris a most momentous treaty was signed, known as the "Paix de Lorris," wherein was assured to the posterity of St. Louis the heritage of the Comte de Toulouse, another of those periodical territorial aggrandizements which ultimately welded the French nation into the whole that it is to-day.

From the juncture of the Canal d'Orleans with the Loire one sees shining in the brilliant sunlight the roof-tops of Orleans, the Aurelianum of the Romans, its hybrid cathedral overtopping all else. It was Victor Hugo who said of this cathedral: "This odious church, which from afar holds so much of promise, and which near by has none," and Hugo undoubtedly spoke the truth.

Orleans is an old city and a cité neuve. Where the river laps its quays, it is old but38 commonplace; back from the river is a strata which is really old, fine Gothic house-fronts and old leaning walls; while still farther from the river, as one approaches the railway station, it is strictly modern, with all the devices and appliances of the newest of the new.

The Orleans of history lies riverwards,—the Orleans where the heart of France pulsed itself again into life in the tragic days which were glorified by "the Maid."

"The countryside of the Orléannais has the monotony of a desert," said an English traveller some generations ago. He was wrong. To do him justice, however, or to do his observations justice, he meant, probably, that, save the river-bottom of the Loire, the great plain which begins with La Beauce and ends with the Sologne has a comparatively uninteresting topography. This is true; but it is not a desert. La Beauce is the best grain-growing region in all France, and the Sologne is now a reclaimed land whose sandy soil has proved admirably adapted to an unusually abundant growth of the vine. So much for this old-time point of view, which to-day has changed considerably.

The Orléannais is one of the most populous and progressive sections of all France, and its39 inhabitants, per square kilometre, are constantly increasing in numbers, which is more than can be said of every département. There are multitudes of tiny villages, and one is scarcely ever out of sight and sound of a habitation.

In the great forest, just to the west of Orleans, are two small villages, each a celebrated battle-ground, and a place of a patriotic pil40grimage on the eighth and ninth of November of each year. They are Coulmiers and Bacon, and here some fugitives from Metz and Sedan, with some young troops exposed to fire for the first time, engaged with the Prussians (in 1870) who had occupied Orleans since mid-October. There is the usual conventional "soldiers' monument,"—with considerably more art about it than is usually seen in America,—before which Frenchmen seemingly never cease to worship.

This same Forêt d'Orleans, one of those wild-woods which so plentifully besprinkle France, has a sad and doleful memory in the traditions of the druidical inhabitants of a former day. Their practices here did not differ greatly from those of their brethren elsewhere, but local history is full of references to atrocities so bloodthirsty that it is difficult to believe that they were ever perpetrated under the guise of religion.

Surrounding the forest are many villages and hamlets, war-stricken all in the dark days of seventy-one, when the Prussians were overrunning the land.

Of all the cities of the Loire, Orleans, Blois, Tours, Angers, and Nantes alone show any spirit of modern progressiveness or of likeness41 to the capital. The rest, to all appearances, are dead, or at least sleeping in their pasts. But they are charming and restful spots for all that, where in melancholy silence sit the old men, while the younger folk, including the very children, are all at work in the neighbouring vineyards or in the wheat-fields of La Beauce.

Meung-sur-Loire and Beaugency sleep on the river-bank, their proud monuments rising high in the background,—the massive tower of Cæsar and a quartette of church spires. Just below Orleans is the juncture of the Loiret and the Loire at St. Mesmin, while only a few kilometres away is Cléry, famed for its associations of Louis XI.

The Loiret is not a very ample river, and is classed by the Minister of Public Works as navigable for but four kilometres of its length. This, better than anything else, should define its relative importance among the great waterways of France. Navigation, as it is known elsewhere, is practically non-existent.

The course of the Loiret is perhaps twelve kilometres all told, but it has given its name to a great French département, though it is doubtless the shortest of all the rivers of France thus honoured.

It first comes to light in the dainty park of42 the Château de la Source, where there are two distinct sources. The first forms a small circular basin, known as the "Bouillon," which leads into another semicircular basin called the "Bassin du Miroir," from the fact that it reflects the façade of the château in its placid surface. Of course, this is all very artificial and theatrical, but it is a pretty conceit nevertheless. The other source, known as the "Grande Source," joins the rivulet some hundreds of yards below the "Bassin du Miroir."

The Château de la Source is a seventeenth-century edifice, of no great architectural beauty in itself, but sufficiently sylvan in its surroundings to give it rank as one of the notable places of pilgrimage for tourists who, said a cynical French writer, "take the châteaux of the Loire tour à tour as they do the morgue, the Moulin Rouge, and the sewers of Paris."

In the early days the château belonged to the Cardinal Briçonnet, and it was here that Bolingbroke, after having been stripped of his titles in England, went into retirement in 1720. In 1722 he received Voltaire, who read him his "Henriade."

In 1815 the invading Prince Eckmühl, with his staff, installed himself in the château, when, after Waterloo, the Prussian and French ar43mies were separated only by a barrier placed midway on the bridge at Orleans. It was here also that the Prussian army was disbanded, on the agreement of the council held at Angerville, near Orleans.

There are three other châteaux on the borders of the Loiret, which are of more than ordinary interest, so far as great country houses and their surroundings go, though their histories are not very striking, with perhaps the exception of the Château de la Fontaine, which has a remarkable garden, laid out by Lenôtre, the designer of the parks at Versailles.

Leaving Orleans by the right bank of the Loire, one first comes to La Chapelle-St. Mesmin. La Chapelle has a church dating from the eleventh century and a château which is to-day the maison de campagne of the Bishop of Orleans. On the opposite bank was the Abbaye de Micy, founded by Clovis at the time of his conversion. A stone cross, only, marks the site to-day.

St. Ay follows next, and is usually set down in the guide-books as "celebrated for good wines." This is not to be denied for a moment, and it is curious to note that the city bears the same name as the famous town in the cham44pagne district, celebrated also for good wine, though of a different kind. The name of the Orléannais Ay is gained from a hermitage founded here by a holy man, who died in the sixth century. His tomb was discovered in 1860, under the choir of the church, which makes it a place of pilgrimage of no little local importance.

At Meung-sur-Loire one should cross the river to Cléry, five kilometres off, seldom if ever visited by casual travellers. But why? Simply because it is overlooked in that universal haste shown by most travellers—who are not students of art or architecture, or deep lovers of history—in making their way to more popular shrines. One will not regret the time taken to visit Cléry, which shared with Our Lady of Embrun the devotions of Louis XI.

Cléry's three thousand pastoral inhabitants of to-day would never give it distinction, and it is only the Maison de Louis XI. and the Basilique de Notre Dame which makes it worth while, but this is enough.

In "Quentin Durward" one reads of the time when the superstitious Louis was held in captivity by the Burgundian, Charles the Bold, and of how the French king made his devotions before the little image, worn in his hat, of the45 Virgin of Cléry; "the grossness of his superstition, none the less than his fickleness, leading him to believe Our Lady of Cléry to be quite a different person from the other object of his devotion, the Madonna of Embrun, a tiny mountain village in southwestern France.

"'Sweet Lady of Cléry,' he exclaimed, clasping his hands and beating his breast as he spoke, 'Blessed Mother of Mercy! thou who art omnipotent with omnipotence, have compassion with me, a sinner! It is true I have sometimes neglected you for thy blessed sister of Embrun; but I am a king, my power is great, my wealth boundless; and were it otherwise, I would double my gabelle on my subjects rather than not pay my debts to you both.'"

Louis endowed the church at Cléry, and the edifice was built in the fine flamboyant style of the period, just previous to his death, which De Commines gives as "le samedy pénultième jour d'Aoust, l'an mil quatre cens quatre-vingtz et trois, à huit heures du soir."

Louis XI. was buried here, and the chief "sight" is of course his tomb, beside which is a flagstone which covers the heart of Charles VIII. The Chapelle St. Jacques, within the church, is ornamented by a series of charming sculptures, and the Chapelle des46 Dunois-Longueville holds the remains of the famous ally of Jeanne d'Arc and members of his family.

In the choir is the massive oaken statue of Our Lady of Cléry (thirteenth century); the very one before which Louis made his vows. There is some old glass in the choir and a series of sculptured stalls, which would make famous a more visited and better known shrine. There is a fine sculptured stone portal to the sacristy, and within there are some magnificent old armoires, and also two chasubles, which saw service in some great church, perhaps here, in the times of Louis himself.

The "Maison de Louis XI.," near the church, is a house of brick, restored in 1651, and now—or until a very recent date—occupied by a community of nuns. In the Grande Rue is another "Maison de Louis XI.;" at least it has his cipher on the painted ceiling. It is now occupied by the Hôtel de la Belle Image. Those who like to dine and sleep where have also dined and slept royal heads will appreciate putting up at this hostelry.

Meung-sur-Loire was the birthplace of Jehan Clopinel, better known as Jean de Meung, who continued Guillaume de Lorris's "Roman de la Rose," the most famous bit of verse produced47 by the trouvères of the thirteenth century. The voice of the troubadour was soon after hushed for ever, but that thirteenth-century masterwork—though by two hands and the respective portions unequal in merit—lives for ever as the greatest of its kind. In memory of the author, Meung has its Rue Jehan de Meung, for want of a more effective or appealing monument.

Dumas opens the history of "Les Trois Mousquétaires" with the following brilliantly romantic lines anent Meung: "Le premier lundi du mois d'Avril, 1625, le bourg de Meung, où naquit l'auteur du 'Roman de la Rose.'" (One of the authors, he should have said, but here is where Dumas nodded, as he frequently did.)

Continuing, one reads: "The town was in a veritable uproar. It was as if the Huguenots were up in arms and the drama of a second Rochelle was being enacted." Really the description is too brilliant and entrancing to be repeated here, and if any one has forgotten his Dumas to the extent that he has forgotten D'Artagnan's introduction to the hostelry of the "Franc Meunier," he is respectfully referred back to that perennially delightful romance.48

Meung was once a Roman fortress, known as Maudunum, and in the eleventh century St. Liphard founded a monastery here.

In the fifteenth century Meung was the prison of François Villon. Poor vagabond as he was then, it has become the fashion to laud both the personality and the poesy of Maître François Villon.

By the orders of Thibaut d'Aussigny, Bishop of Orleans, Villon was confined in a strong tower attached to the side of the clocher of the parish church of St. Liphard, and which adjoined the château de plaisance belonging to the bishop. Primarily this imprisonment was due to a robbery in which the poet had been concerned at Orleans. He spent the whole of the summer in this dungeon, which was overrun with rats, and into which he had to be lowered by ropes. As his food consisted of bread and water only, his sufferings at this time were probably greater than at any other period in his life. Here the burglar-poet remained until October, 1461, when Louis XI. visited Meung, and, to mark the occasion, ordered the release of all prisoners. For this delivery, Villon, according to the accounts of his life, appears to have been genuinely grateful to the king.

At Beaugency, seven kilometres from Meung,49 one comes upon an architectural and historical treat which is unexpected.

In the eleventh century Beaugency was a fief of the bishopric of Amiens, and its once strong château was occupied by the Barons de Landry, the last of whom died, without children, in the thirteenth century. Philippe-le-Bel bought the fief and united it with the Comté de Blois. It was made an independent comté of itself in 1569, and in 1663 became definitely an appanage of Orleans. The Prince de Galles took Beaugency in 1359, the Gascons in 1361, Duguesclin in 1370 and again in 1417; in 1421 and in 1428 it was taken by the English, from whom it was delivered by Jeanne d'Arc in 1429. Internal wars and warfares continued for another hundred and fifty years, finally culminating in one of the grossest scenes which had been enacted within its walls,—the bloody revenge against the Protestants, encouraged doubtless by the affair of St. Bartholomew's night at Paris.

The ancient square donjon of the eleventh century, known as the Tour de César, still looms high above the town. It must be one of the hugest keeps in all France. The old château of the Dunois is now a charitable institution, but reflects, in a way, the splendour of its fourteenth-century inception, and its Salle50 de Jeanne d'Arc, with its great chimneypiece, is worthy to rank with the best of its kind along the Loire. The spiral staircase, of which the Loire builders were so fond, is admirable here, and dates from 1530.

The Hôtel de Ville of Beaugency is a charming edifice of the very best of Renaissance, which many more pretentious structures of the period are not. It dates from 1526, and was entirely restored—not, however, to its detriment, as frequently happens—in the last years of the nineteenth century. Its charm, nevertheless, lies mostly in its exterior, for little remains of value within except a remarkable series of old embroideries taken from the choir of the old abbey of Beaugency.

The Église de Notre Dame is a Romanesque structure with Gothic interpolations. It is not bad in its way, but decidedly is not remarkable as mediæval churches go.

The old streets of Beaugency contain a dazzling array of old houses in wood and stone, and in the Rue des Templiers is a rare example of Romanesque civil architecture; at least the type is rare enough in the Orléannais, though more frequently seen in the south of France. The Tour St. Firmin dates from 1530, and is all that remains of a church which stood51 here up to revolutionary times. The square ruined towers known as the Porte Tavers are relics of the city's old walls and gates, and are all that are left to mark the ancient enclosure.

The Tour du Diable and the house of the ruling abbot remain to suggest the power and magnificence of the great abbey which was built here in the tenth century. In 1567 it was burned, and later restored, but beyond the two features just mentioned there is nothing to indicate its former uses, the remaining structures having passed into private hands and being devoted to secular uses.

The old bridge which crosses the Loire at this point is most curious, and dates from various epochs. It is 440 metres in length, and is composed of twenty-six arches, one of which dates from the fourteenth century, when bridge-building was really an art. Eight of the present-day arches are of wood, and on the second is a monolith surmounted by a figure of Christ in bronze, replacing a former chapel to St. Jacques. A chapel on a bridge is not a unique arrangement, but few exist to-day, one of the most famous being, perhaps, that on the ruined bridge of St. Bénezet at Avignon.

Altogether, Beaugency, as it sleeps its life away after the strenuous days of the middle52 ages, is more lovable by far than a great metropolis.

The traveller is well repaid who makes a stop at Beaugency a part of a three days' gentle ramble among the usually neglected towns and villages of the Orléannais and the Blaisois, instead of rushing through to Blois by express-train, which is what one usually does.

Southward one's route lies through pleasant vineyards, on one side the Sologne, and on the other the Coteau de Guignes, which latter ranks as quite the best among the vine-growing districts of the Orléannais.

Near Tavers is a natural curiosity in the shape of the "Fontaine des Sables Mouvants," where the sands of a tiny spring boil and bubble like a miniature geyser.

Mer, another small town, follows, twelve kilometres farther on. Like Beaugency it is a somnolent bourg, and the life of the peasant folk round about, who go to market on one day at Beaugency and on another at Blois, and occasionally as far away as Orleans, is much the same as it was a century ago.

There is a Boulevard de la Gare and a Grande Rue at Mer, the latter leading to a fine Gothic church with a fifteenth-century tower, which is admirable in every way, and forms53 a beacon by land for many miles around. The primitive church at Mer dates from the eleventh century, the side walls, however, being all that remain of that period. There is a sculptured pulpit of the seventeenth century, and a great painting, which looks ancient and is certainly a masterful work of art, representing an "Adoration of the Magi."

When all is said and done, it is its irresistible and inexpressible charm which makes Mer well-beloved, rather than any great wealth of artistic atmosphere of any nature.

Away to the south, across the Loire to Muides, runs the route to Chambord, through the Sologne, where immediately the whole aspect of life changes from that on the borders of the rich grain-lands of the Orléannais and La Beauce.

All the way from Beaugency to Blois the Loire threads its way through a lovely country, whose rolling slopes, back from the river, are surmounted here and there by windmills, a not very frequent adjunct to the landscape of France, except in the north.

Near Mer is Menars, with its eighteenth-century château of La Pompadour; Suèvres, the site of an ancient Roman city; the lowlands lying before Chambord; St. Die; Montlivault;54 St. Claude, and a score of little villages which are entrancing in their old-world aspect even in these days of progress. This completes the panorama to Blois which, with the Blaisois, forms the borderland between the Orléannais and Touraine.

Before reaching Blois, Menars, at any rate, commands attention. It fronts upon the Loire, but is practically upon the northern border of the Forêt de Blois, hence properly belongs to the Blaisois. Menars was made a rendezvous for the chase by the wily and pleasure-loving La Pompadour, who quartered herself at the château, which afterward passed to her brother, De Marigny.

Before the Revolution, Menars was the seat of a marquisate, of which the land was bought by Louis XV. for his famous, or infamous, maîtresse. The property has frequently changed hands since that day, but its gardens and terraces, descending toward the river-bank, mark it as one of those coquette establishments, with which France was dotted in the eighteenth century.

These establishments possessed enough of luxurious appointments to be classed as fitting for the butterflies of the time, but in no way, so far as the architectural design or the55 artistic details were concerned, were any of them worthy to be classed with the great domestic châteaux of the early years of the Renaissance.56

The Blésois or Blaisois was the ancient name given to the petit pays which made a part of the government of the Orléannais. It was, and is, the borderland between the Orléannais and Touraine, and, with its capital, Blois, the city of counts, was a powerful territory in its own right, in spite of the allegiance which it owed to the Crown. Twenty leagues in length by thirteen in width, it was bounded on the north by the Dunois and the Orléannais, on the east by Berry, on the south by Touraine, and on the west by Touraine and the Vendomois.

Blois, its capital, was famed ever in the annals of the middle ages, and to-day no city in the Loire valley possesses more sentimental interest for the traveller than does Blois.

To the eastward lay the sands of the Sologne, and southward the ample and fruitful Touraine, hence Blois's position was one of su57preme importance, and there is no wonder that it proved to be the scene of so many momentous events of history.

The present day Department of the Loir et Cher was carved out from the Blaisois, the Vendomois, and the Orléannais. The Baisois was, in olden time, one of the most important of the petits gouvernements of all the kingdom, and gave to Blois a line of counts who rivalled in power and wealth the churchmen of Tours and the dukes of Brittany. Gregory of Tours is the first historian who makes mention of the ancient Pagus Blensensis.

One must not tell the citizen of Blois that it is at Tours that one hears the best French spoken. Everybody knows this, but the inhabitant of the Blaisois will not admit it, and, in truth, to the stranger there is not much apparent difference. Throughout this whole region he understands and makes himself understood with much more facility than in any other part of France.

For one thing, not usually recalled, Blois should be revered and glorified. It was the native place of Lenoir, who invented the instrument which made possible the definite determination of the metric system of measurement.

One reads in Bernier's "Histoire de Blois"58 that the inhabitants are "honest, gallant, and polite in conversation, and of a delicate and diffident temperament." This was written nearly a century ago, but there is no excuse for one's changing the opinion to-day unless, as was the misfortune of the writer, he runs up against an unusually importunate vender of post-cards or an aggressive garçon de café.

Blois, among all the cities of the Loire, is the favourite with the tourist. Why this should be is an enigma. It is overburdened, at times, with droves of tourists, and this in itself is a detraction in the eyes of many.

Perhaps it is because here one first meets a great château of state; and certainly the Château de Blois lives in one's memory more than any other château in France.

Much has been written of Blois, its counts, its château, and its many and famous hôtels of the nobility, by writers of all opinions and abilities, from those old chroniclers who wrote59 of the plots and intrigues of other days to those critics of art and architecture who have discovered—or think they have discovered—that Da Vinci designed the famous spiral staircase.

From this one may well gather that Blois is the foremost château of all the Loire in popularity and theatrical effect. Truly this is so, but it is by no manner of means the most lovable; indeed, it is the least lovable of all that great galaxy which begins at Blois and ends at Nantes. It is a show-place and not much more, and partakes in every form and feature—as one sees it to-day—of the attributes of a museum, and such it really is. All of its former gorgeousness is still there, and all the banalities of the later period when Gaston of Orleans built his ugly wing, for the "personally conducted" to marvel at, and honeymoon couples to envy. The French are quite fond of visiting this shrine themselves, but usually it is the young people and their mammas, and detached couples of American and English birth that one most sees strolling about the courts and apartments were formerly lords and ladies and cavaliers moved and plotted.

The great château of the Counts of Blois is built upon an inclined rock which rises above60 the roof-tops of the lower town quite in fairy-book fashion,—

Commonly referred to as the Château de Blois, it is really composed of four separate and distinct foundations; the original château of the counts; the later addition of Louis XII.; the palace of François I., and the most unsympathetically and dismally disposed pavillon of Gaston of Orleans.

The artistic qualities of the greater part of the distinct edifices which go to make up the château as it stands to-day are superb, with the exception of that great wing of Gaston's, before mentioned, which is as cold and unfeeling as the overrated palace at Versailles.61

The Comtes de Chatillon built that portion just to the right of the present entrance; Louis XII., the edifice through which one enters the inner court and which extends far to the left, including also the chapel immediately to the rear; while François Premier, who here as elsewhere let his unbounded Italian proclivities have full sway, built the extended wing to the left of the inner court and fronting on the present Place du Château, formerly the Place Royale.

Immediately to the left, in the Basse Cour de Château, are the Hôtel d'Amboise, the Hôtel d'Épernon, and farther away, in the Rue St. Honore, the Hôtel Sardini, the Hôtel d'Alluye, and a score of others belonging to the nobility of other days; all of them the scenes of many stirring and gallant events in Renaissance times.

This is hardly the place for a discussion of the merits or demerits of any particular artistic style, but the frequently repeated expression of Buffon's "Le style, c'est l'homme" may well be paraphrased into "L'art, c'est l'époque." In fact one finds at all times imprinted upon the architectural style of any period the current mood bred of some historical event or a passing fancy.62

At Blois this is particularly noticeable. As an architectural monument the château is a picturesque assemblage of edifices belonging to many different epochs, and, as such, shows, as well as any other document of contemporary times, the varying ambitions and emotions of its builders, from the rude and rough manners of the earliest of feudal times through the highly refined Renaissance details of the imaginative brain of François, down to the base concoction of the elder Mansart, produced at the commands of Gaston of Orleans.

The whole gamut, from the gay and winsome to the sad and dismal, is found here.

The escutcheons of the various occupants are plainly in evidence,—the swan pierced by an arrow of the first Counts of Blois; the63 ermine of Anne de Bretagne; the porcupine of the Ducs d'Orleans, and the salamander of François Premier.

In the earliest structure were to be seen all the attributes of a feudal fortress, towers and walls pierced with narrow loopholes, and damp, dark dungeons hidden away in the thick walls. Then came a structure which was less of a fortress and more habitable, but still a stronghold, though having ample and decorative doorways and windows, with curious sculptures and rich framings. Then the pompous Renaissance with escaliers and balcons à jour, balustrades crowning the walls, arabesques enriching the pilasters and walls, and elaborate cornices here, there, and everywhere,—all bespeaking the gallantry and taste of the roi-chevalier. Finally came the cold, classic features of the period of the brother of Louis XIII., decidedly the worst and most unlivable and unlovely architecture which France has ever produced. All these features are plain in the general scheme of the Château de Blois to-day, and doubtless it is this that makes the appeal; too much loveliness, as at Chenonceaux or Azay-le-Rideau, staggers the modern mortal by the sheer impossibility of its modern attainment.

In plan the Château de Blois forms an irreg64ular square situated at the apex of a promontory high above the surface of the Loire, and practically behind the town itself. The building has a most picturesque aspect, and, to those who know, gives practically a history of the château architecture of the time. Abandoned, mutilated, and dishonoured from time to time, the structure gradually took on new forms until the thick walls underlying the apartment known to-day as the Salle des États—probably the most ancient portion of all—were overshadowed by the great richness of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. One early fragment was entirely enveloped in the structure which was built by François Premier, the ancient Tour de Château Regnault, or De Moulins, or Des Oubliettes, as it was variously known, and from the outside this is no longer visible.

From the platform one sees a magnificent panorama of the city and the far-reaching Loire, which unrolls itself southward and northward for many leagues, its banks covered by rich vineyards and crowned by thick forests.

The building of Louis XII. presents its brick-faced exterior in black and red lozenge shapes, with sculptured window-frames, squarely upon the little tree-bordered place of to-day, which65 in other times formed a part of that magnificent terrace which looked down upon the roof of the Église St. Nicolas, and the Jesuit Church of the Immaculate Conception, and the silvery belt of the Loire itself.

On the west façade of this vast conglomerate structure one sees the effigy of the porcupine, that weird symbol adopted by the family of Orleans.

The choice of this ungainly animal—in spite of which it is most decorative in outline—was due to the first Louis, who was Duc d'Orleans. In the year 1393 Louis founded the66 order of the porcupine, in honour of the birth of Charles, his eldest son, who was born to him by Valentine de Milan. The legend which accompanied the adoption of the symbol—though often enough it was missing in the sculptured representations—was Cominus et eminus, which had its origin in the belief that the porcupine could defend himself in a near attack, but that when he himself attacked, he fought from afar by launching forth his spines.

Naturalists will tell you that the porcupine does no such thing; but in those days it was evidently believed that he did, and in many, if not all, of the sculptured effigies that one sees of the beast there is a halo of detached spines forming a background as if they were really launching themselves forth in mid-air.

Above this central doorway, or entrance to the courtyard, is a niche in which is a modern equestrian statue of Louis XII., replacing a more ancient one destroyed at the Revolution. This old statue, it is claimed, was an admirable work of art in its day, and the present statue is thought to be a replica of it.

It originally bore the following inscription—a verse written by Fausto Andrelini, the king's favourite poet. 67

According to an old French description this old statue was: "très beau et très agréable ainsy que tous ses portraits l'ont représenté, comme celui qui est au grand portail de Bloys."

Above rises a balustrade with fantastic gargoyles with the pinnacles and fleurons of the window gables all very ornate, the whole topped off with a roofing of slate.

Blois, in its general aspect, is fascinating; but it is not sympathetic, and this is not surprising when one remembers men and women who worked their deeds of bloody daring within its walls.

The murders and other acts of violence and treason which took place here are interesting enough, but one cannot but feel, when he views the chimneypiece before which the Duc de Guise was standing when called to his death in the royal closet, that the men of whom the bloody tales of Blois are told quite deserved their fates.

One comes away with the impression of it68 all stamped only upon the mind, not graven upon the heart. Political intrigue to-day, if quite as vulgar, is less sordid. Bigotry and ambition in those days allowed few of the finer feelings to come to the surface, except with regard to the luxuriance of surroundings. Of this last there can be no question, and Blois is as characteristically luxurious as any of the magnificent edifices which lodged the royalty and nobility of other days, throughout the valley of the Loire.