The Project Gutenberg EBook of From Squire to Squatter, by Gordon Stables

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: From Squire to Squatter

A Tale of the Old Land and the New

Author: Gordon Stables

Release Date: December 11, 2011 [EBook #38277]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FROM SQUIRE TO SQUATTER ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Gordon Stables

"From Squire to Squatter"

"A Tale of the Old Land and the New"

Chapter One.

Book I—At Burley Old Farm.

“Ten to-morrow, Archie.”

“So you’ll be ten years old to-morrow, Archie?”

“Yes, father; ten to-morrow. Quite old, isn’t it? I’ll soon be a man, dad. Won’t it be fun, just?”

His father laughed, simply because Archie laughed. “I don’t know about the fun of it,” he said; “for, Archie lad, your growing a man will result in my getting old. Don’t you see?”

Archie turned his handsome brown face towards the fire, and gazed at it—or rather into it—for a few moments thoughtfully. Then he gave his head a little negative kind of a shake, and, still looking towards the fire as if addressing it, replied:

“No, no, no; I don’t see it. Other boys’ fathers may grow old; mine won’t, mine couldn’t, never, never.”

“Dad,” said a voice from the corner. It was a very weary, rather feeble, voice. The owner of it occupied a kind of invalid couch, on which he half sat and half reclined—a lad of only nine years, with a thin, pale, old-fashioned face, and big, dark, dreamy eyes that seemed to look you through and through as you talked to him.

“Dad.”

“Yes, my dear.”

“Wouldn’t you like to be old really?”

“Wel—,” the father was beginning.

“Oh,” the boy went on, “I should dearly love to be old, very old, and very wise, like one of these!” Here his glance reverted to a story-book he had been reading, and which now lay on his lap.

His father and mother were used to the boy’s odd remarks. Both parents sat here to-night, and both looked at him with a sort of fond pity; but the child’s eyes had half closed, and presently he dropped out of the conversation, and to all intents and purposes out of the company.

“Yes,” said Archie, “ten is terribly old, I know; but is it quite a man though? Because mummie there said, that when Solomon became a man, he thought, and spoke, and did everything manly, and put away all his boy’s things. I shouldn’t like to put away my bow and arrow—what say, mum? I shan’t be altogether quite a man to-morrow, shall I?”

“No, child. Who put that in your head?”

“Oh, Rupert, of course! Rupert tells me everything, and dreams such strange dreams for me.”

“You’re a strange boy yourself, Archie.”

His mother had been leaning back in her chair. She now slowly resumed her knitting. The firelight fell on her face: it was still young, still beautiful—for the lady was but little over thirty—yet a shade of melancholy had overspread it to-night.

The firelight came from huge logs of wood, mingled with large pieces of blazing coals and masses of half-incandescent peat. A more cheerful fire surely never before burned on a hearth. It seemed to take a pride in being cheerful, and in making all sorts of pleasant noises and splutterings. There had been bark on those logs when first heaped on, and long white bunches of lichen, that looked like old men’s beards; but tongues of fire from the bubbling, caking coals had soon licked those off, so that both sticks and peat were soon aglow, and the whole looked as glorious as an autumn sunset.

And firelight surely never before fell on cosier room, nor on cosier old-world furniture. Dark pictures, in great gilt frames, hung on the walls, almost hiding it; dark pictures, but with bright colours standing out in them, which Time himself had not been able to dim; albeit he had cracked the varnish. Pictures you could look into—look in through almost—and imagine figures that perhaps were not in them at all; pictures of old-fashioned places, with quaint, old-fashioned people and animals; pictures in which every creature or human being looked contented and happy. Pictures from masters’ hands many of them, and worth far more than their weight in solid gold.

And the firelight fell on curious brackets, and on a tall corner-cabinet filled with old delf and china; fell on high, narrow-backed chairs, and on one huge carved-oak chest that took your mind away back to centuries long gone by and made you half believe that there must have been “giants in those days.”

The firelight fell and was reflected from silver cups, and goblets, and candlesticks, and a glittering shield that stood on a sideboard, their presence giving relief to the eye. Heavy, cosy-looking curtains depended from the window cornices, and the door itself was darkly draped.

“Ten to-morrow. How time does fly!”

It was the father who now spoke, and as he did so his hand was stretched out as if instinctively, till it lay on the mother’s lap. Their eyes met, and there seemed something of sadness in the smile of each.

“How time does fly!”

“Dad!”

The voice came once more from the corner.

“Dad! For years and years I’ve noticed that you always take mummie’s hand and just look like that on the night before Archie’s birthday. Father, why—”

But at that very moment the firelight found something else to fall upon—something brighter and fairer by far than anything it had lit up to-night. For the door-curtain was drawn back, and a little, wee, girlish figure advanced on tiptoe and stood smiling in the middle of the room, looking from one to the other. This was Elsie, Rupert’s twin-sister. His “beautiful sister” the boy called her, and she was well worthy of the compliment. Only for a moment did she stand there, but as she did so, with her bonnie bright face, she seemed the one thing that had been needed to complete the picture, the centre figure against the sombre, almost solemn, background.

The fire blazed more merrily now; a jet of white smoke, that had been spinning forth from a little mound of melting coal, jumped suddenly into flame; while the biggest log cracked like a popgun, and threw off a great red spark, which flew half-way across the room.

Next instant a wealth of dark-brown hair fell on Archie’s shoulder, and soft lips were pressed to his sun-dyed cheek, then bright, laughing eyes looked into his.

“Ten to-morrow, Archie! Aren’t you proud?”

Elsie now took a footstool, and sat down close beside her invalid brother, stretching one arm across his chest protectingly; but she shook her head at Archie from her corner.

“Ten to-morrow, you great big, big brother Archie,” she said.

Archie laughed right merrily.

“What are you going to do all?”

“Oh, such a lot of things! First of all, if it snows—”

“It is snowing now, Archie, fast.”

“Well then I’m going to shoot the fox that stole poor Cock Jock. Oh, my poor Cock Jock! We’ll never see him again.”

“Shooting foxes isn’t sport, Archie.”

“No, dad; it’s revenge.”

The father shook his head.

“Well, I mean something else.”

“Justice?”

“Yes, that is it. Justice, dad. Oh, I did love that cock so! He was so gentlemanly and gallant, father. Oh, so kind! And the fox seized him just as poor Jock was carrying a crust of bread to the old hen Ann. He threw my bonnie bird over his shoulder and ran off, looking so sly and wicked. But I mean to kill him!

“Last time I fired off Branson’s gun was at a magpie, a nasty, chattering, unlucky magpie. Old Kate says they’re unlucky.”

“Did you kill the magpie, Archie?”

“No, I don’t think I hurt the magpie. The gun must have gone off when I wasn’t looking; but it knocked me down, and blackened all my shoulder, because it pushed so. Branson said I didn’t grasp it tight enough. But I will to-morrow, when I’m killing the fox. Rupert, you’ll stuff the head, and we’ll hang it in the hall. Won’t you, Roup?” Rupert smiled and nodded.

“And I’m sure,” he continued, “the Ann hen was so sorry when she saw poor Cock Jock carried away.”

“Did the Ann hen eat the crust?”

“What, father? Oh, yes, she did eat the crust! But I think that was only out of politeness. I’m sure it nearly choked her.”

“Well, Archie, what will you do else to-morrow?”

“Oh, then, you know, Elsie, the fun will only just be beginning, because we’re going to open the north tower of the castle. It’s already furnished.”

“And you’re going to be installed as King of the North Tower?” said his father.

“Installed, father? Rupert, what does that mean?”

“Led in with honours, I suppose.”

“Oh, father, I’ll instal myself; or Sissie there will; or old Kate; or Branson, the keeper, will instal me. That’s easy. The fun will all come after that.”

Burley Old Farm, as it was called—and sometimes Burley Castle—was, at the time our story opens, in the heyday of its glory and beauty. Squire Broadbent, Archie’s father, had been on it for a dozen years and over. It was all his own, and had belonged to a bachelor uncle before his time. This uncle had never made the slightest attempt to cause two blades of grass to grow where only one had grown before. Not he. He was well content to live on the little estate, as his father had done before him, so long as things paid their way; so long as plenty of sleek beasts were seen in the fields in summer, or wading knee-deep in the straw-yard in winter; so long as pigs, and poultry, and feather stock of every conceivable sort, made plenty of noise about the farm-steading, and there was plenty of human life about, the old Squire had been content. And why shouldn’t he have been? What does a North-country farmer need, or what has he any right to long for, if his larder and coffers are both well filled, and he can have a day on the stubble or moor, and ride to the hounds when the crops are in?

But his nephew was more ambitious. The truth is he came from the South, and brought with him what the honest farmer folks of the Northumbrian borders call a deal of new-fangled notions. He had come from the South himself, and he had not been a year in the place before he went back, and in due time returned to Burley Old Farm with a bonnie young bride. Of course there were people in the neighbourhood who did not hesitate to say, that the Squire might have married nearer home, and that there was no accounting for taste. For all this and all that, both the Squire and his wife were not long in making themselves universal favourites all round the countryside; for they went everywhere, and did everything; and the neighbours were all welcome to call at Burley when they liked, and had to call when Mrs Broadbent issued invitations.

Well, the Squire’s dinners were truly excellent, and when afterwards the men folk joined the ladies in the big drawing-room, the evenings flew away so quickly that, as carriage time came, nobody could ever believe it was anything like so late.

The question of what the Squire had been previously to his coming to Burley was sometimes asked by comparative strangers, but as nobody could or cared to answer explicitly, it was let drop. Something in the South, in or about London, or Deal, or Dover, but what did it matter? he was “a jolly good fellow—ay, and a gentleman every inch.” Such was the verdict.

A gentleman the Squire undoubtedly was, though not quite the type of build, either in body or mind, of the tall, bony, and burly men of the North—men descended from a race of ever-unconquered soldiers, and probably more akin to the Scotch than the English.

Sitting here in the green parlour to-night, with the firelight playing on his smiling face as he talked to or teased his eldest boy, Squire Broadbent was seen to advantage. Not big in body, and rather round than angular, inclining even to the portly, with a frank, rosy face and a bold blue eye, you could not have been in his company ten minutes without feeling sorry you had not known him all his life.

Amiability was the chief characteristic of Mrs Broadbent. She was a refined and genuine English lady. There is little more to say after that.

But what about the Squire’s new-fangled notions? Well, they were really what they call “fads” now-a-days, or, taken collectively, they were one gigantic fad. Although he had never been in the agricultural interest before he became Squire, even while in city chambers theoretical farming had been his pet study, and he made no secret of it to his fellow-men.

“This uncle of mine,” he would say, “whom I go to see every Christmas, is pretty old, and I’m his heir. Mind,” he would add, “he is a genuine, good man, and I’ll be genuinely sorry for him when he goes under. But that is the way of the world, and then I’ll have my fling. My uncle hasn’t done the best for his land; he has been content to go—not run; there is little running about the dear old boy—in the same groove as his fathers, but I’m going to cut out a new one.”

The week that the then Mr Broadbent was in the habit of spending with his uncle, in the festive season, was not the only holiday he took in the year. No; for regularly as the month of April came round, he started for the States of America, and England saw no more of him till well on in June, by which time the hot weather had driven him home.

But he swore by the Yankees; that is, he would have sworn by them, had he sworn at all. The Yankees in Mr Broadbent’s opinion were far ahead of the English in everything pertaining to the economy of life, and the best manner of living. He was too much of a John Bull to admit that the Americans possessed any superiority over this tight little isle, in the matter of either politics or knowledge of warfare. England always had been, and always would be, mistress of the seas, and master of and over every country with a foreshore on it. “But,” he would say, “look at the Yanks as inventors. Why, sir, they beat us in everything from button-hook. Look at them as farmers, especially as wheat growers and fruit raisers. They are as far above Englishmen, with their insular prejudices, and insular dread of taking a step forward for fear of going into a hole, as a Berkshire steam ploughman is ahead of a Skyeman with his wooden turf-turner. And look at them at home round their own firesides, or look at their houses outside and in, and you will have some faint notion of what comfort combined with luxury really means.”

It will be observed that Mr Broadbent had a bold, straightforward way of talking to his peers. He really had, and it will be seen presently that he had, “the courage of his own convictions,” to use a hackneyed phrase.

He brought those convictions with him to Burley, and the courage also.

Why, in a single year—and a busy, bustling one it had been—the new Squire had worked a revolution about the place. Lucky for him, he had a well-lined purse to begin with, or he could hardly have come to the root of things, or made such radical reforms as he did.

When he first took a look round the farm-steading, he felt puzzled where to begin first. But he went to work steadily, and kept it up, and it is truly wonderful what an amount of solid usefulness can be effected by either man or boy, if he has the courage to adopt such a plan.

Chapter Two.

A Chip of the Old Block.

It was no part of Squire Broadbent’s plan to turn away old and faithful servants. He had to weed them though, and this meant thinning out to such an extent that not over many were left.

The young and healthy creatures of inutility had to shift; but the very old, the decrepit—those who had become stiff and grey in his uncle’s service—were pensioned off. They were to stay for the rest of their lives in the rural village adown the glen—bask in the sun in summer, sit by the fire of a winter, and talk of the times when “t’old Squire was aboot.”

The servants settled with, and fresh ones with suitable “go” in them established in their place, the live stock came in for reformation.

“Saint Mary! what a medley!” exclaimed the Squire, as he walked through the byres and stables, and past the styes. “Everything bred anyhow. No method in my uncle’s madness. No rules followed, no type. Why the quickest plan will be to put them all to the hammer.”

This was cutting the Gordian-knot with a vengeance, but it was perhaps best in the long run.

Next came renovation of the farm-steading itself; pulling down and building, enlarging, and what not, and while this was going on, the land itself was not being forgotten. Fences were levelled and carted away, and newer and airier ones put up, and for the most part three and sometimes even five fields were opened into one. There were woods also to be seen to. The new Squire liked woods, but the trees in some of these were positively poisoning each other. Here was a larch-wood, for instance—those logs with the long, grey lichens on them are part of some of the trees. So closely do the larches grow together, so white with moss, so stunted and old-looking, that it would have made a merry-andrew melancholy to walk among them. What good were they? Down they must come, and down they had come; and after the ground had been stirred up a bit, and left for a summer to let the sunshine and air into it, all the hill was replanted with young, green, smiling pines, larches, and spruces, and that was assuredly an improvement. In a few years the trees were well advanced; grass and primroses grew where the moss had crept about, and the wood in spring was alive with the song of birds.

The mansion-house had been left intact. Nothing could have added much to the beauty of that. It stood high up on a knoll, with rising park-like fields behind, and at some considerable distance the blue slate roofs of the farm-steading peeping up through the greenery of the trees. A solid yellow-grey house, with sturdy porch before the hall door, and sturdy mullioned windows, one wing ivy-clad, a broad sweep of gravel in front, and beyond that, lawns and terraces, and flower and rose gardens. And the whole overlooked a river or stream, that went winding away clear and silvery till it lost itself in wooded glens.

The scenery was really beautiful all round, and in some parts even wild; while the distant views of the Cheviot Hills lent a charm to everything.

There was something else held sacred by the Squire as well as the habitable mansion, and that was Burley Old Castle. Undoubtedly a fortress of considerable strength it had been in bygone days, when the wild Scots used to come raiding here, but there was no name for it now save that of a “ruin.” The great north tower still stood firm and bold, and three walls of the lordly hall, its floor green with long, rank grass; the walls themselves partly covered with ivy, with broom growing on the top, which was broad enough for the half-wild goats to scamper along.

There was also the donjon keep, and the remains of a fosse; but all the rest of this feudal castle had been unceremoniously carted away, to erect cowsheds and pig-styes with it.

“So sinks the pride of former days,

When glory’s thrill is o’er.”

No, Squire Broadbent did not interfere with the castle; he left it to the goats and to Archie, who took to it as a favourite resort from the time he could crawl.

But these—all these—new-fangled notions the neighbouring squires and farmers bold could easily have forgiven, had Broadbent not carried his craze for machinery to the very verge of folly. So they thought. Such things might be all very well in America, but they were not called for here. Extraordinary mills driven by steam, no less wonderful-looking harrows, uncanny-like drags and drilling machines, sowing and reaping machines that were fearfully and wonderfully made, and ploughs that, like the mills, were worked by steam.

Terrible inventions these; and even the men that were connected with them had to be brought from the far South, and did not talk a homely, wholesome lingua, nor live in a homely, wholesome way.

His neighbours confessed that his crops were heavier, and the cereals and roots finer; but they said to each other knowingly, “What about the expense of down-put?” And as far as their own fields went, the plough-boy still whistled to and from his work.

Then the new live stock, why, type was followed; type was everything in the Squire’s eye and opinion. No matter what they were, horses, cattle, pigs, sheep, and feather stock, even the dogs and birds were the best and purest of the sort to be had.

But for all the head-shaking there had been at first, things really appeared to prosper with the Squire; his big, yellow-painted wagons, with their fine Clydesdale horses, were as well known in the district and town of B— as the brewer’s dray itself. The “nags” were capitally harnessed. What with jet-black, shining leather, brass-work that shone like burnished gold, and crimson-flashing fringes, it was no wonder that the men who drove them were proud, and that they were favourites at every house of call. Even the bailiff himself, on his spirited hunter, looked imposing with his whip in his hand, and in his spotless cords.

Breakfast at Burley was a favourite meal, and a pretty early one, and the capital habit of inviting friends thereto was kept up. Mrs Broadbent’s tea was something to taste and remember; while the cold beef, or that early spring lamb on the sideboard, would have converted the veriest vegetarian as soon as he clapped eyes on it.

On his spring lamb the Squire rather prided himself, and he liked his due meed of praise for having reared it. To be sure he got it; though some of the straightforward Northumbrians would occasionally quizzingly enquire what it cost him to put on the table.

Squire Broadbent would not get out of temper whatever was said, and really, to do the man justice, it must be allowed that there was a glorious halo of self-reliance around his head; and altogether such spirit, dash, and independence with all he said and did, that those who breakfasted with him seemed to catch the infection. Their farms and they themselves appeared quite behind the times, when viewed in comparison with Broadbent’s and with Broadbent himself.

If ever a father was loved and admired by a son, the Squire was that man, and Archie was that particular son. His father was Archie’s beau ideal indeed of all that was worth being, or saying, or knowing, in this world; and Rupert’s as well.

He really was his boys’ hero, but behaved more to them as if he had been just a big brother. It was a great grief to both of them that Rupert could not join in their games out on the lawn in summer—the little cricket matches, the tennis tournaments, the jumping, and romping, and racing. The tutor was younger than the Squire by many years, but he could not beat him in any manly game you could mention.

Yes, it was sad about Rupert; but with all the little lad’s suffering and weariness, he was such a sunny-faced chap. He never complained, and when sturdy, great, brown-faced Archie carried him out as if he had been a baby, and laid him on the couch where he could witness the games, he was delighted beyond description.

I’m quite sure that the Squire often and often kept on playing longer than he would otherwise have done just to please the child, as he was generally called. As for Elsie, she did all her brother did, and a good deal more besides, and yet no one could have called her a tom girl.

As the Squire was Archie’s hero, I suppose the boy could not help taking after his hero to some extent; but it was not only surprising but even amusing to notice how like to his “dad” in all his ways Archie had at the age of ten become. The same in walk, the same in talk, the same in giving his opinion, and the same in bright, determined looks. Archie really was what his father’s friends called him, “a chip of the old block.”

He was a kind of a lad, too, that grown-up men folks could not help having a good, romping lark with. Not a young farmer that ever came to the place could have beaten Archie at a race; but when some of them did get hold of him out on the lawn of an evening, then there would be a bit of fun, and Archie was in it.

These burly Northumbrians would positively play a kind of pitch and toss with him, standing in a square or triangle and throwing him back and fore as if he had been a cricket ball. And there was one very tall, wiry young fellow who treated Archie as if he had been a sort of dumb-bell, and took any amount of exercise out of him; holding him high aloft with one hand, swaying him round and round and up and down, changing hands, and, in a word, going through as many motions with the laughing boy as if he had been inanimate.

I do not think that Archie ever dressed more quickly in his life, than he did on the morning of that auspicious day which saw him ten years old. To tell the truth, he had never been very much struck over the benefits of early rising, especially on mornings in winter. The parting between the boy and his warm bed was often of a most affecting character. The servant would knock, and the gong would go, and sometimes he would even hear his father’s voice in the hall before he made up his mind to tear himself away.

But on this particular morning, no sooner had he rubbed his eyes and began to remember things, than he sprang nimbly to the floor. The bath was never a terrible ordeal to Archie, as it is to some lads. He liked it because it made him feel light and buoyant, and made him sing like the happy birds in spring time; but to-day he did think it would be a saving of time to omit it. Yes, but it would be cowardly, and on this morning of all mornings; so in he plunged, and plied the sponge manfully. He did not draw up the blinds till well-nigh dressed. For all he could see when he did do so, he might as well have left them down. The windows—the month was January—were hard frozen; had it been any other day, he would have paused to admire the beautiful frost foliage and frost ferns that nature had etched on the panes. He blew his breath on the glass instead, and made a clean round hole thereon.

Glorious! It had been snowing pretty heavily, but now the sky was clear. The footprints of the wily fox could be tracked. Archie would follow him to his den in the wild woods, and his Skye terriers would unearth him. Then the boy knelt to pray, just reviewing the past for a short time before he did so, and thinking what a deal he had to be thankful for; how kind the good Father was to have given him such parents, such a beautiful home, and such health, and thinking too what a deal he had to be sorry for in the year that was gone; then he gave thanks, and prayer for strength to resist temptation in the time to come; and, it is needless to say, he prayed for poor invalid Rupert.

When he got up from his knees he heard the great gong sounded, and smiled to himself to think how early he was. Then he blew on the pane and looked out again. The sky was blue and clear, and there was not a breath of wind; the trees on the lawn, laden with their weight of powdery snow, their branches bending earthwards, especially the larches and spruces, were a sight to see. And the snow-covered lawn itself, oh, how beautiful! Archie wondered if the streets of heaven even could be more pure, more dazzlingly white.

Whick, whick, whick, whir-r-r-r-r!

It was a big yellow-billed blackbird, that flew out with startled cry from a small Austrian pine tree. As it did so, a cloud of powdery snow rose in the air, showing how hard the frost was.

Early though it was—only a little past eight—Archie found his father and mother in the breakfast-room, and greetings and blessings fell on his head; brief but tender.

By-and-bye the tutor came in, looking tired; and Archie exulted over him, as cocks crow over a fallen foe, because he was down first.

Mr Walton was a young man of five or six and twenty, and had been in the family for over three years, so he was quite an old friend. Moreover, he was a man after the Squire’s own heart; he was manly, and taught Archie manliness, and had a quiet way of helping him out of every difficulty of thought or action. Besides, Archie and Rupert liked him.

After breakfast Archie went up to see his brother, then downstairs, and straight away out through the servants’ hall to the barn-yards. He had showers of blessings, and not a few gifts from the servants; but old Scotch Kate was most sincere, for this somewhat aged spinster really loved the lad.

At the farm-steading he had many friends to see, both hairy and feathered. He found some oats, which he scattered among the last, and laughed to see them scramble, and to hear them talk. Well, Archie at all events believed firmly that fowls can converse. One very lovely red game bird, came boldly up and pecked his oats from Archie’s palm. This was the new Cock Jock, a son of the old bird, which the fox had taken. The Ann hen was there too. She was bold, and bonnie, and saucy, and seemed quite to have given up mourning for her lost lord. Ann came at Archie’s call, flew on to his wrist, and after steadying herself and grumbling a little because Archie moved his arm too much, she shoved her head and neck into the boy’s pocket, and found oats in abundance. That was Ann’s way of doing business, and she preferred it.

The ducks were insolent and noisy; the geese, instead of taking higher views of life, as they are wont to do, bent down their stately necks, and went in for the scramble with the rest. The hen turkeys grumbled a great deal, but got their share nevertheless; while the great gobbler strutted around doing attitudes, and rustling himself, his neck and head blood-red and blue, and every feather as stiff as an oyster-shell. He looked like some Indian chief arrayed for the war-path.

Having hurriedly fed his feathered favourites, Archie went bounding off to let out a few dogs. He opened the door and went right into their house, and the consequence was that one of the Newfoundlands threw him over in the straw, and licked his face; and the Skye terriers came trooping round, and they also paid their addresses to him, some of the young ones jumping over his head, while Archie could do nothing for laughing. When he got up he sang out “Attention!” and lo! and behold the dogs, every one looking wiser than another, some with their considering-caps on apparently, and their heads held knowingly to one side.

“Attention!” cried the boy. “I am going to-day to shoot the fox that ran off with the hen Ann’s husband. I shall want some of you. You Bounder, and you little Fuss, and you Tackier, come.”

And come those three dogs did, while the rest, with lowered tails and pitiful looks, slunk away to their straw. Bounder was an enormous Newfoundland, and Fuss and Tackier were terriers, the former a Skye, the latter a very tiny but exceedingly game Yorkie.

Yonder, gun on shoulder, came tall, stately Branson, the keeper, clad in velveteen, with gaiters on. Branson was a Northumbrian, and a grand specimen too. He might have been somewhat slow of speech, but he was not slow to act whenever it came to a scuffle with poachers, and this last was not an unfrequent occurrence.

“My gun, Branson?”

“It’s in the kitchen, Master Archie, clean and ready; and old Kate has put a couple of corks in it, for fear it should go off.”

“Oh, it is loaded then—really loaded!”

“Ay, lad; and I’ve got to teach you how to carry it. This is your first day on the hill, mind, and a rough one it is.”

Archie soon got his leggings on, and his shot-belt and shooting-cap and everything else, in true sportsman fashion.

“What!” he said at the hall door, when he met Mr Walton, “am I to have my tutor with me to-day?”

He put strong emphasis on the last word.

“You know, Mr Walton, that I am ten to-day. I suppose I am conceited, but I almost feel a man.”

His tutor laughed, but by no means offensively.

“My dear Archie, I am going to the hill; but don’t imagine I’m going as your tutor, or to look after you. Oh, no! I want to go as your friend.”

This certainly put a different complexion on the matter.

Archie considered for a moment, then replied, with charming condescension:

“Oh, yes, of course, Mr Walton! You are welcome, I’m sure, to come as a friend.”

Chapter Three.

A Day of Adventure.

If we have any tears all ready to flow, it is satisfactory to know that they will not be required at present. If we have poetic fire and genius, even these gifts may for the time being be held in reservation. No “Ode to a Dying Fox” or “Elegy on the Death and Burial of Reynard” will be necessary. For Reynard did not die; nor was he shot; at least, not sufficiently shot.

In one sense this was a pity. It resulted in mingled humiliation and bitterness for Archie and for the dogs. He had pictured to himself a brief moment of triumph when he should return from the chase, bearing in his hand the head of his enemy—the murderer of the Ann hen’s husband—and having the brush sticking out of his jacket pocket; return to be crowned, figuratively speaking, with festive laurel by Elsie, his sister, and looked upon by all the servants with a feeling of awe as a future Nimrod.

In another sense it was not a pity; that is, for the fox. This sable gentleman had enjoyed a good run, which made him hungry, and as happy as only a fox can be who knows the road through the woods and wilds to a distant burrow, where a bed of withered weeds awaits him, and where a nice fat hen is hidden. When Reynard had eaten his dinner and licked his chops, he laid down to sleep, no doubt laughing in his paw at the boy’s futile efforts to capture or kill him, and promising himself the pleasure of a future moonlight visit to Burley Old Farm, from which he should return with the Ann hen herself on his shoulder.

Yes, Archie’s hunt had been unsuccessful, though the day had not ended without adventure, and he had enjoyed the pleasures of the chase.

Bounder, the big Newfoundland, first took up the scent, and away he went with Fuss and Tackier at his heels, the others following as well as they could, restraining the dogs by voice and gesture. Through the spruce woods, through a patch of pine forest, through a wild tangle of tall, snow-laden furze, out into the open, over a stream, and across a wide stretch of heathery moorland, round quarries and rocks, and once more into a wood. This time it was stunted larch, and in the very centre of it, close by a cairn of stones, Bounder said—and both Fuss and Tackier acquiesced—that Reynard had his den. But how to get him out?

“You two little chaps get inside,” Bounder seemed to say. “I’ll stand here; and as soon as he bolts, I shall make the sawdust fly out of him, you see!”

Escape for the fox seemed an impossibility. He had more than one entrance to his den, but all were carefully blocked up by the keeper except his back and front door. Bounder guarded the latter, Archie went to watch by the former.

“Keep quiet and cool now, and aim right behind the shoulder.”

Quiet and cool indeed! how could he? Under such exciting circumstances, his heart was thumping like a frightened pigeon’s, and his cheeks burning with the rush of blood to them.

He knelt down with his gun ready, and kept his eyes on the hole. He prayed that Reynard might not bolt by the front door, for that would spoil his sport.

The terrier made it very warm for the fox in his den. Small though the little Yorkie was, his valour was wonderful. Out in the open Reynard could have killed them one by one, but here the battle was unfair, so after a few minutes of a terrible scrimmage the fox concluded to bolt.

Archie saw his head at the hole, half protruded then drawn back, and his heart thumped now almost audibly.

Would he come? Would he dare it?

Yes, the fox dared it, and came. He dashed out with a wild rush, like a little hairy hurricane. “Aim behind the shoulder!” Where was the shoulder? Where was anything but a long sable stream of something feathering through the snow?

Bang! bang! both barrels. And down rolled the fox. Yes, no. Oh dear, it was poor Fuss! The fox was half a mile away in a minute.

Fuss lost blood that stained the snow brown as it fell on it. And Archie shed bitter tears of sorrow and humiliation.

“Oh, Fuss, my dear, dear doggie!” he cried, “I didn’t mean to hurt you.”

The Skye terrier was lying on the keeper’s knees and having a snow styptic.

Soon the blood ceased to flow, and Fuss licked his young master’s hands, and presently got down and ran around and wanted to go to earth again; and though Archie felt he could never forgive himself for his awkwardness, he was so happy to see that Fuss was not much the worse after all.

But there would be no triumphant home-returning; he even began to doubt if ever he would be a sportsman. Then Branson consoled him, and told him he himself didn’t do any better when he first took to the hill.

“It is well,” said Mr Walton, laughing, “that you didn’t shoot me instead.”

“Ye-es,” said Archie slowly, looking at Fuss. It was evident he was not quite convinced that Mr Walton was right.

“Fuss is none the worse,” cried Branson. “Oh, I can tell you it does these Scotch dogs good to have a drop or two of lead in them! It makes them all the steadier, you know.”

About an hour after, to his exceeding delight, Archie shot a hare. Oh joy! Oh day of days! His first hare! He felt a man now, from the top of his Astrachan cap to the toe caps of his shooting-boots.

Bounder picked it up, and brought it and laid it at Archie’s feet.

“Good dog! you shall carry it.”

Bounder did so most delightedly.

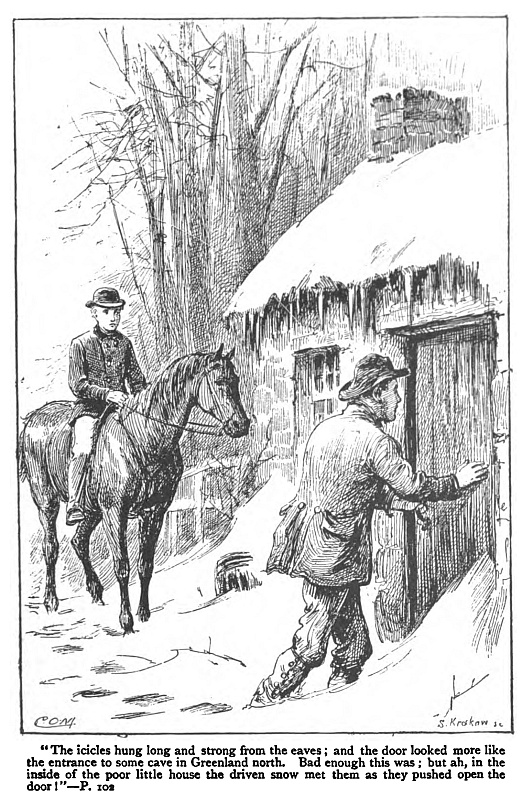

They stopped at an outlying cottage on their way home. It was a long, low, thatched building, close by a wood, a very humble dwelling indeed.

A gentle-faced widow woman opened to their knock. She looked scared when she saw them, and drew back.

“Oh!” she said, “I hope Robert hasn’t got into trouble again?”

“No, no, Mrs Cooper, keep your mind easy, Bob’s a’ right at present. We just want to eat our bit o’ bread and cheese in your sheiling.”

“And right welcome ye are, sirs. Come in to the fire. Here’s a broom to brush the snow fra your leggins.”

Bounder marched in with the rest, with as much swagger and independence as if the cottage belonged to him. Mrs Cooper’s cat determined to defend her hearth and home against such intrusion, and when Bounder approached the former, she stood on her dignity, back arched, tail erect, hair on end from stem to stern, with her ears back, and green fire lurking in her eyes. Bounder stood patiently looking at her. He would not put down the hare, and he could not defend himself with it in his mouth; so he was puzzled. Pussy, however, brought matters to a crisis. She slapped his face, then bolted right up the chimney. Bounder put down the hare now, and gave a big sigh as he lay down beside it.

“No, Mrs Cooper, Bob hasn’t been at his wicked work for some time. He’s been gi’en someone else a turn I s’pose, eh?”

“Oh, sirs,” said the widow, “it’s no wi’ my will he goes poachin’! If his father’s heid were above the sod he daren’t do it. But, poor Bob, he’s all I have in the world, and he works hard—sometimes.”

Branson laughed. It was a somewhat sarcastic laugh; and young Archie felt sorry for Bob’s mother, she looked so unhappy.

“Ay, Mrs Cooper, Bob works hard sometimes, especially when settin’ girns for game. Ha! ha! Hullo!” he added, “speak of angels and they appear. Here comes Bob himself!”

Bob entered, looked defiantly at the keeper, but doffed his cap and bowed to Mr Walton and Archie. “Mother,” he said, “I’m going out.”

“Not far, Bob, lad; dinner’s nearly ready.”

Bob had turned to leave, but he wheeled round again almost fiercely. He was a splendid young specimen of a Borderer, six feet if an inch, and well-made to boot. No extra flesh, but hard and tough as copper bolts. “Denner!” he growled. “Ay, denner to be sure—taties and salt! Ha! and gentry live on the fat o’ the land! If I snare a rabbit, if I dare to catch one o’ God’s own cattle on God’s own hills, I’m a felon; I’m to be taken and put in gaol—shot even if I dare resist! Yas, mother, I’ll be in to denner,” and away he strode.

“Potatoes and salt!” Archie could not help thinking about that. And he was going away to his own bright home and to happiness. He glanced round him at the bare, clay walls, with their few bits of daubs of pictures, and up at the blackened rafters, where a cheese stood—one poor, hard cheese—and on which hung some bacon and onions. He could not repress a sigh, almost as heart-felt as that which Bounder gave when he lay down beside the hare.

When the keeper and tutor rose to go, Archie stopped behind with Bounder just a moment. When they came out, Bounder had no hare.

Yet that hare was the first Archie had shot, and—well, he had meant to astonish Elsie with this proof of his prowess; but the hare was better to be left where it was—he had earned a blessing.

The party were in the wood when Bob Cooper, the poacher, sprang up as if from the earth and confronted them.

“I came here a purpose,” he said to Branson. “This is not your wood; even if it was I wouldn’t mind. What did you want at my mother’s hoose?”

“Nothing; and I’ve nothing to say to ye.”

“Haven’t ye? But ye were in our cottage. It’s no for nought the glaud whistles.”

“I don’t want to quarrel,” said Branson, “especially after speakin’ to your mother; she’s a kindly soul, and I’m sorry for her and for you yoursel’, Bob.”

Bob was taken aback. He had expected defiance, exasperation, and he was prepared to fight.

Archie stood trembling as these two athletes looked each other in the eyes.

But gradually Bob’s face softened; he bit his lip and moved impatiently. The allusion to his mother had touched his heart.

“I didn’t want sich words, Branson. I—may be I don’t deserve ’em. I—hang it all, give me a grip o’ your hand!”

Then away went Bob as quickly as he had come.

Branson glanced at his retreating figure one moment.

“Well,” he said, “I never thought I’d shake hands wi’ Bob Cooper! No matter; better please a fool than fecht ’im.”

“Branson!”

“Yes, Master Archie.”

“I don’t think Bob’s a fool; and I’m sure that, bad as he is, he loves his mother.”

“Quite right, Archie,” said Mr Walton.

Archie met his father at the gate, and ran towards him to tell him all his adventures about the fox and the hare. But Bob Cooper and everybody else was forgotten when he noticed what and whom he had behind him. The “whom” was Branson’s little boy, Peter; the “what” was one of the wildest-looking—and, for that matter, one of the wickedest-looking—Shetland ponies it is possible to imagine. Long-haired, shaggy, droll, and daft; but these adjectives do not half describe him.

“Why, father, wherever—”

“He’s your birthday present, Archie.”

The boy actually flushed red with joy. His eyes sparkled as he glanced from his father to the pony and back at his father again.

“Dad,” he said at last, “I know now what old Kate means about ‘her cup being full.’ Father, my cup overflows!”

Well, Archie’s eyes were pretty nearly overflowing anyhow.

Chapter Four.

In the Old Castle Tower.

They were all together that evening in the green parlour as usual, and everybody was happy and merry. Even Rupert was sitting up and laughing as much as Elsie. The clatter of tongues prevented them hearing Mary’s tapping at the door; and the carpet being so thick and soft, she was not seen until right in the centre of the room.

“Why, Mary,” cried Elsie, “I got such a start, I thought you were a ghost!”

Mary looks uneasily around her.

“There be one ghost, Miss Elsie, comes out o’ nights, and walks about the old castle.”

“Was that what you came in to tell us, Mary?”

“Oh, no, sir! If ye please, Bob Cooper is in the yard, and he wants to speak to Master Archie. I wouldn’t let him go if I were you, ma’am.”

Archie’s mother smiled. Mary was a privileged little parlour maiden, and ventured at times to make suggestions.

“Go and see what he wants, dear,” said his mother to Archie.

It was a beautiful clear moonlight night, with just a few white snow-laden clouds lying over the woods, no wind and never a hush save the distant and occasional yelp of a dog.

“Bob Cooper!”

“That’s me, Master Archie. I couldn’t rest till I’d seen ye the night. The hare—”

“Oh! that’s really nothing, Bob Cooper!”

“But allow me to differ. It’s no’ the hare altogether. I know where to find fifty. It was the way it was given. Look here, lad, and this is what I come to say, Branson and you have been too much for Bob Cooper. The day I went to that wood to thrash him, and I’d hae killed him, an I could. Ha! ha! I shook hands with him! Archie Broadbent, your father’s a gentleman, and they say you’re a chip o’ t’old block. I believe ’em, and look, see, lad, I’ll never be seen in your preserves again. Tell Branson so. There’s my hand on’t. Nay, never be afear’d to touch it. Good-night. I feel better now.”

And away strode the poacher, and Archie could hear the sound of his heavy tread crunching through the snow long after he was out of sight.

“You seem to have made a friend, Archie,” said his father, when the boy reported the interview.

“A friend,” added Mr Walton with a quiet smile, “that I wouldn’t be too proud of.”

“Well,” said the Squire, “certainly Bob Cooper is a rough nut, but who knows what his heart may be like?”

Archie’s room in the tower was opened in state next day. Old Kate herself had lit fires in it every night for a week before, though she never would go up the long dark stair without Peter. Peter was only a mite of a boy, but wherever he went, Fuss, the Skye terrier, accompanied him, and it was universally admitted that no ghost in its right senses would dare to face Fuss.

Elsie was there of course, and Rupert too, though he had to be almost carried up by stalwart Branson. But what a glorious little room it was when you were in it! A more complete boy’s own room could scarcely be imagined. It was a beau ideal; at least Rupert and Archie and Elsie thought so, and even Mr Walton and Branson said the same.

Let me see now, I may as well try to describe it, but much must be left to imagination. It was not a very big room, only about twelve feet square; for although the tower appeared very large from outside, the abnormal thickness of its walls detracted from available space inside it. There was one long window on each side, and a chair and small table could be placed on the sill of either. But this was curtained off at night, when light came from a huge lamp that depended from the ceiling, and the rays from which fought for preference with those from the roaring fire on the stone hearth. The room was square. A door, also curtained, gave entrance from the stairway at one corner, and at each of two other corners were two other doors leading into turret chambers, and these tiny, wee rooms were very delightful, because you were out beyond the great tower when you sat in them, and their slits of windows granted you a grand view of the charming scenery everywhere about.

The furniture was rustic in the extreme—studiously so. There was a tall rocking-chair, a great dais or sofa, and a recline for Rupert—“poor Rupert” as he was always called—the big chair was the guest’s seat.

The ornaments on the walls had been principally supplied by Branson. Stuffed heads of foxes, badgers, and wild cats, with any number of birds’ and beasts’ skins, artistically mounted. There were also heads of horned deer, bows and arrows—these last were Archie’s own—and shields and spears that Uncle Ramsay had brought home from savage wars in Africa and Australia. The dais was covered with bear skins, and there was quite a quantity of skins on the floor instead of a carpet. So the whole place looked primeval and romantic.

The bookshelf was well supplied with readable tales, and a harp stood in a corner, and on this, young though she was, Elsie could already play.

The guest to-night was old Kate. She sat in the tall chair in a corner opposite the door, Branson occupied a seat near her, Rupert was on his recline, and Archie and Elsie on a skin, with little Peter nursing wounded Fuss in a corner.

That was the party. But Archie had made tea, and handed it round; and sitting there with her cup in her lap, old Kate really looked a strange, weird figure. Her face was lean and haggard, her eyes almost wild, and some half-grey hair peeped from under an uncanny-looking cap of black crape, with long depending strings of the same material.

Old Kate was housekeeper and general female factotum. She was really a distant relation of the Squire, and so had it very much her own way at Burley Old Farm.

She came originally from “just ayant the Border,” and had a wealth of old-world stories to tell, and could sing queer old bits of ballads too, when in the humour.

Old Kate, however, said she could not sing to-night, for she felt as yet unused to the place; and whether they (the boys) believed in ghosts or not she (Kate) did, and so, she said, had her father before her. But she told stories—stories of the bloody raids of long, long ago, when Northumbria and the Scottish Borders were constantly at war—stories that kept her hearers enthralled while they listened, and to which the weird looks and strange voice of the narrator lent a peculiar charm.

Old Kate was just in the very midst of one of these when, twang! one of the strings of Elsie’s harp broke. It was a very startling sound indeed; for as it went off it seemed to emit a groan that rang through the chamber, and died away in the vaulted roof. Elsie crept closer to Archie, and Peter with Fuss drew nearer the fire.

The ancient dame, after being convinced that the sound was nothing uncanny, proceeded with her narrative. It was a long one, with an old house in it by the banks of a winding river in the midst of woods and wilds—a house that, if its walls had been able to speak, could have told many a marrow-freezing story of bygone times.

There was a room in this house that was haunted. Old Kate was just coming to this, and to the part of her tale on which the ghosts on a certain night of the year always appeared in this room, and stood over a dark stain in the centre of the floor.

“And ne’er a ane,” she was saying, “could wash that stain awa’. Weel, bairns, one moonlicht nicht, and at the deadest hoor o’ the nicht, nothing would please the auld laird but he maun leave his chaimber and go straight along the damp, dreary, long corridor to the door o’ the hauntid room. It was half open, and the moon’s licht danced in on the fleer. He was listening—he was looking—”

But at this very moment, when old Kate had lowered her voice to a whisper, and the tension at her listeners’ heart-strings was the greatest, a soft, heavy footstep was heard coming slowly, painfully as it might be, up the turret stairs.

To say that every one was alarmed would but poorly describe their feelings. Old Kate’s eyes seemed as big as watch-glasses. Elsie screamed, and clung to Archie.

“Who—oo—’s—Who’s there?” cried Branson, and his voice sounded fearful and far away.

No answer; but the steps drew nearer and nearer. Then the curtain was pushed aside, and in dashed—what? a ghost?—no, only honest great Bounder.

Bounder had found out there was something going on, and that Fuss was up there, and he didn’t see why he should be left out in the cold. That was all; but the feeling of relief when he did appear was unprecedented.

Old Kate required another cup of tea after that. Then Branson got out his fiddle from a green baize bag; and if he had not played those merry airs, I do not believe that old Kate would have had the courage to go downstairs that night at all.

Archie’s pony was great fun at first. The best of it was that he had never been broken in. The Squire, or rather his bailiff, had bought him out of a drove; so he was, literally speaking, as wild as the hills, and as mad as a March hare. But he soon knew Archie and Elsie, and, under Branson’s supervision, Scallowa was put into training on the lawn. He was led, he was walked, he was galloped. But he reared, and kicked, and rolled whenever he thought of it, and yet there was not a bit of vice about him.

Spring had come, and early summer itself, before Scallowa permitted Archie to ride him, and a week or two after this the difficulty would have been to have told which of the two was the wilder and dafter, Archie or Scallowa. They certainly had managed to establish the most amicable relations. Whatever Scallowa thought, Archie agreed to, and vice versa, and the pair were never out of mischief. Of course Archie was pitched off now and then, but he told Elsie he did not mind it, and in fact preferred it to constant uprightness: it was a change. But the pony never ran away, because Archie always had a bit of carrot in his pocket to give him when he got up off the ground.

Mr Walton assured Archie that these carrots accounted for his many tumbles. And there really did seem to be a foundation of truth about this statement. For of course the pony had soon come to know that it was to his interest to throw his rider, and acted accordingly. So after a time Archie gave the carrot-payment up, and matters were mended.

It was only when school was over that Archie went for a canter, unless he happened to get up very early in the morning for the purpose of riding. And this he frequently did, so that, before the summer was done, Scallowa and Archie were as well known over all the countryside as the postman himself.

Archie’s pony was certainly not very long in the legs, but nevertheless the leaps he could take were quite surprising.

On the second summer after Archie got this pony, both horse and rider were about perfect in their training, and in the following winter he appeared in the hunting-field with the greatest sang-froid, although many of the farmers, on their weight-carrying hunters, could have jumped over Archie, Scallowa, and all. The boy had a long way to ride to the hounds, and he used to start off the night before. He really did not care where he slept. Old Kate used to make up a packet of sandwiches for him, and this would be his dinner and breakfast. Scallowa he used to tie up in some byre, and as often as not Archie would turn in beside him among the straw. In the morning he would finish the remainder of Kate’s sandwiches, make his toilet in some running stream or lake, and be as fresh as a daisy when the meet took place.

Both he and Scallowa were somewhat uncouth-looking. Elsie, his sister, had proposed that he should ride in scarlet, it would look so romantic and pretty; but Archie only laughed, and said he would not feel at home in such finery, and his “Eider Duck”—as he sometimes called the pony—would not know him. “Besides, Elsie,” he said, “lying down among straw with scarlets on wouldn’t improve them.”

But old Kate had given him a birthday present of a little Scotch Glengarry cap with a real eagle’s feather, and he always wore this in the hunting-field. He did so for two reasons; first, it pleased old Kate; and, secondly, the cap stuck to his head; no breeze could blow it off.

It was not long before Archie was known in the field as the “Little Demon Huntsman.” And, really, had you seen Scallowa and he feathering across a moor, his bonnet on the back of his head, and the pony’s immense mane blowing straight back in the wind, you would have thought the title well earned. In a straight run the pony could not keep up with the long-legged horses; but Archie and he could dash through a wood, and even swim streams, and take all manner of short cuts, so that he was always in at the death.

The most remarkable trait in Archie’s riding was that he could take flying leaps from heights: only a Shetland pony could have done this. Archie knew every yard of country, and he rather liked heading his Lilliputian nag right away for a knoll or precipice, and bounding off it like a roebuck or Scottish deerhound. The first time he was observed going straight for a bank of this kind he created quite a sensation. “The boy will be killed!” was the cry, and every lady then drew rein and held her breath.

Away went Scallowa, and they were on the bank, in the air, and landed safely, and away again in less time that it takes me to tell of the exploit.

The secret of the lad’s splendid management of the pony was this: he loved Scallowa, and Scallowa knew it. He not only loved the little horse, but studied his ways, so he was able to train him to do quite a number of tricks, such as lying down “dead” to command, kneeling to ladies—for Archie was a gallant lad—trotting round and round circus-fashion, and ending every performance by coming and kissing his master. Between you and me, reader, a bit of carrot had a good deal to do with the last trick, if not with the others also.

It occurred to this bold boy once that he might be able to take Scallowa up the dark tower stairs to the boy’s own room. The staircase was unusually wide, and the broken stones in it had been repaired with logs of wood. He determined to try; but he practised riding him blindfolded first. Then one day he put him at the stairs; he himself went first with the bridle in his hand.

What should he do if he failed? That is a question he did not stop to answer. One thing was quite certain, Scallowa could not turn and go down again. On they went, the two of them, all in the dark, except that now and then a slit in the wall gave them a little light and, far beneath, a pretty view of the country. On and on, and up and up, till within ten feet of the top.

Here Scallowa came to a dead stop, and the conversation between Archie and his steed, although the latter did not speak English, might have been as follows: “Come on, ‘Eider Duck’!”

“Not a step farther, thank you.”

“Come on, old horsie! You can’t turn, you know.”

“No; not another step if I stay here till doomsday in the afternoon. Going upstairs becomes monotonous after a time. No; I’ll be shot if I budge!”

“You’ll be shot if you don’t. Gee up, I say; gee up!”

“Gee up yourself; I’m going to sleep.”

“I say, Scallowa, look here.”

“What’s that, eh? a bit of carrot? Oh, here goes?” And in a few seconds more Scallowa was in the room, and had all he could eat of cakes and carrots. Archie was so delighted with his success that he must go to the castle turret, and halloo for Branson and old Kate to come and see what he had got in the tower.

Old Kate’s astonishment knew no bounds, and Branson laughed till his sides were sore. Bounder, the Newfoundland, appeared also to appreciate the joke, and smiled from lug to lug.

“How will you get him down?”

“Carrots,” said Archie; “carrots, Branson. The ‘Duck’ will do anything for carrots.”

The “Duck,” however, was somewhat nervous at first, and half-way downstairs even the carrots appeared to have lost their charm.

While Archie was wondering what he should do now, a loud explosion seemed to shake the old tower to its very foundation. It was only Bounder barking in the rear of the pony. But the sound had the desired effect, and down came the “Duck,” and away went Archie, so that in a few minutes both were out on the grass.

And here Scallowa must needs relieve his feelings by lying down and rolling; while great Bounder, as if he had quite appreciated all the fun of the affair, and must do something to allay his excitement, went tearing round in a circle, as big dogs do, so fast that it was almost impossible to see anything of him distinctly. He was a dark shape et preterea nihil.

But after a time Scallowa got near to the stair, which only proves that there is nothing in reason you cannot teach a Shetland pony, if you love him and understand him.

The secret lies in the motto, “Fondly and firmly.” But, as already hinted, a morsel of carrot comes in handy at times.

Chapter Five.

“Boys will be Boys.”

Bob Cooper was as good as his word, which he had pledged to Archie on that night at Burley Old Farm, and Branson never saw him again in the Squire’s preserves.

Nor had he ever been obliged to compeer before the Squire himself—who was now a magistrate—to account for any acts of trespass in pursuit of game on the lands of other lairds. But this does not prove that Bob had given up poaching. He was discreetly silent about this matter whenever he met Archie.

He had grown exceedingly fond of the lad, and used to be delighted when he called at his mother’s cottage on his “Eider Duck.” There was always a welcome waiting Archie here, and whey to drink, which, it must be admitted, is very refreshing on a warm summer’s day.

Well, Bob on these occasions used to show Archie how to make flies, or busk hooks, and gave him a vast deal of information about outdoor life and sport generally.

The subject of poaching was hardly ever broached; only once, when he and Archie were talking together in the little cottage, Bob himself volunteered the following information:

“The gentry folks, Master Archie, think me a terrible man; and they wonder I don’t go and plough, or something. La! they little know I’ve been brought up in the hills. Sport I must hae. I couldna live away from nature. But I’m never cruel. Heigho! I suppose I must leave the country, and seek for sport in wilder lands, where the man o’ money doesn’t trample on the poor. Only one thing keeps me here.”

He glanced out of the window as he spoke to where his old mother was cooking dinner al fresco—boiling a pot as the gipsy does, hung from a tripod.

“I know, I know,” said Archie.

“How old are you now, Master Archie?”

“Going on for fourteen.”

“Is that all? Why ye’re big eno’ for a lad o’ seventeen!”

This was true. Archie was wondrous tall, and wondrous brown and handsome. His hardy upbringing and constant outdoor exercise, in summer’s shine or winter’s snow, fully accounted for his stature and looks.

“I’m almost getting too big for my pony.”

“Ah! no, lad; Shetlands’ll carry most anything.”

“Well, I must be going, Bob Cooper. Good-bye.”

“Good-bye, Master Archie. Ah! lad, if there were more o’ your kind and your father’s in the country, there would be fewer bad men like—like me.”

“I don’t like to hear you saying that, Bob. Couldn’t you be a good man if you liked? You’re big enough.”

The poacher laughed.

“Yes,” he replied, “I’m big enough; but, somehow, goodness don’t strike right home to me like. It don’t come natural—that’s it.”

“My brother Rupert says it is so easy to be good, if you read and pray God to teach and help you.”

“Ah, Master Archie, your brother is good himself, but he doesn’t know all.”

“My brother Rupert bade me tell you that; but, oh, Bob, how nice he can speak. I can’t. I can fish and shoot, and ride ‘Eider Duck;’ but I can’t say things so pretty as he can. Well, good-bye again.”

“Good-bye again, and tell your brother that I can’t be good all at one jump like, but I’ll begin to try mebbe. So long.”

Archie Broadbent might have been said to have two kinds of home education; one was thoroughly scholastic, the other very practical indeed. The Squire was one in a hundred perhaps. He was devoted to his farm, and busied himself in the field, manually as well as orally. I mean to say that he was of such an active disposition that, while superintending and giving advice and orders, he put his hand to the wheel himself. So did Mr Walton, and whether it was harvest-time or haymaking, you would have found Squire Broadbent, the tutor, and Archie hard at it, and even little Elsie doing a little.

I would not like to say that the Squire was a radical, but he certainly was no believer in the benefits of too much class distinction. He thought Burns was right when he said—

“A man’s a man for a’ that.”

Was he any the less liked or less respected by his servants, because he and his boy tossed hay in the same field with them? I do not think so, and I know that the work always went more merrily on when they were there; and that laughing and even singing could be heard all day long. Moreover, there was less beer drank, and more tea. The Squire supplied both liberally, and any man might have which he chose. Consequently there was less, far less, tired-headedness and languor in the evening. Why, it was nothing uncommon for the lads and lasses of Burley Old Farm to meet together on the lawn, after a hard day’s toil, and dance for hours to the merry notes of Branson’s fiddle.

We have heard of model farms; this Squire’s was one; but the servants, wonderful to say, were contented. There was never such a thing as grumbling heard from one year’s end to the other.

Christmas too was always kept in the good, grand old style. Even a yule log, drawn from the wood, was considered a property of the performances; and as for good cheer, why there was “lashins” of it, as an Irishman would say, and fun “galore,” to borrow a word from beyond the Border.

Mr Walton was a scholarly person, though you might not have thought so, had you seen him mowing turnips with his coat off. He, however, taught nothing to Archie or Rupert that might not have some practical bearing on his after life. Such studies as mathematics and algebra were dull, in a manner of speaking; Latin was taught because no one can understand English without it; French and German conversationally; geography not by rote, but thoroughly; and everything else was either very practical and useful, or very pleasant.

Music Archie loved, but did not care to play; his father did not force him; but poor Rupert played the zither. He loved it, and took to it naturally.

Rupert got stronger as he grew older, and when Archie was fourteen and he thirteen, the physician gave good hopes; and he was even able to walk by himself a little. But to some extent he would be “Poor Rupert” as long as he lived.

He read and thought far more than Archie, and—let me whisper it—he prayed more fervently.

“Oh, Roup,” Archie would say, “I should like to be as good as you! Somehow, I don’t feel to need to pray so much, and to have the Lord Jesus so close to me.”

It was a strange conceit this, but Rupert’s answer was a good one.

“Yes, Archie, I need comfort more; but mind you, brother, the day may come when you’ll want comfort of this kind too.”

Old Kate really was a queer old witch of a creature, superstitious to a degree. Here is an example: One day she came rushing—without taking time to knock even—into the breakfast parlour.

“Oh, Mistress Broadbent, what a ghast I’ve gotten!”

“Dear me!” said the Squire’s wife; “sit down and tell us. What is it, poor Kate?”

“Oh! Oh!” she sighed. “Nae wonder my puir legs ached. Oh! sirs! sirs!

“Ye ken my little pantry? Well, there’s been a board doon on the fleer for ages o’ man, and to-day it was taken out to be scrubbit, and what think ye was reveeled?”

“I couldn’t guess.”

“Words, ’oman; words, printed and painted on the timmer—‘Sacred to the Memory of Dinah Brown, Aged 99.’ A tombstone, ’oman—a wooden gravestone, and me standin’ on’t a’ these years.”

Here the Squire was forced to burst out into a hearty laugh, for which his wife reprimanded him by a look.

There was no mistake about the “wooden tombstone,” but that this was the cause of old Kate’s rheumatism one might take the liberty to doubt.

Kate was a staunch believer in ghosts, goblins, fairies, kelpies, brownies, spunkies, and all the rest of the supernatural family; and I have something to relate in connection with this, though it is not altogether to the credit of my hero, Archie.

Old Kate and young Peter were frequent visitors to the room in the tower, for the tea Archie made, and the fires he kept on, were both most excellent in their way.

“Boys will be boys,” and Archie was a little inclined to practical joking. It made him laugh, so he said, and laughing made one fat.

It happened that, one dark winter’s evening, old Kate was invited up into the tower, and Branson with Peter came also. Archie volunteered a song, and Branson played many a fine old air on his fiddle, so that the first part of the evening passed away pleasantly and even merrily enough. Old Kate drank cup after cup of tea as she sat in that weird old chair, and, by-and-by, Archie, the naughty boy that he was, led the conversation round to ghosts. The ancient dame was in her element now; she launched forth into story after story, and each was more hair-stirring than its predecessor.

Elsie and Archie occupied their favourite place on a bear’s skin in front of the low fire; and while Kate still droned on, and Branson listened with eyes and mouth wide open, the boy might have been noticed to stoop down, and whisper something in his sister’s ear.

Almost immediately after a rattling of chains could be heard in one of the turrets. Both Kate and Branson started, and the former could not be prevailed upon to resume her story till Archie lit a candle and walked all round the room, drawing back the turret curtains to show no one was there.

Once again old Kate began, and once again chains were heard to rattle, and a still more awesome sound followed—a long, low, deep-bass groan, while at the same time, strange to say, the candle in Archie’s hand burnt blue. To add to the fearsomeness of the situation, while the chain continued to rattle, and the groaning now and then, there was a very appreciable odour of sulphur in the apartment. This was the climax. Old Kate screamed, and the big keeper, Branson, fell on his knees in terror. Even Elsie, though she had an inkling of what was to happen, began to feel afraid.

“There now, granny,” cried Archie, having carried the joke far enough, “here is the groaning ghost.” As he spoke he produced a pair of kitchen bellows, with a musical reed in the pipe, which he proceeded to sound in old Kate’s very face, looking a very mischievous imp while he did so.

“Oh,” said old Kate, “what a scare the laddie has given me. But the chain?”

Archie pulled a string, and the chain rattled again. “And the candle? That was na canny.”

“A dust of sulphur in the wick, granny.” Big Branson looked ashamed of himself, and old Kate herself began to smile once more.

“But how could ye hae the heart to scare an old wife sae, Master Archie?”

“Oh, granny, we got up the fun just to show you there were no such things as ghosts. Rupert says—and he should know, because he’s always reading—that ghosts are always rats or something.”

“Ye maunna frichten me again, laddie. Will ye promise?”

“Yes, granny, there’s my hand on it. Now sit down and have another cup of tea, and Elsie will play and sing.”

Elsie could sing now, and sweet young voice she had, that seemed to carry you to happier lands. Branson always said it made him feel a boy again, wandering through the woods in summer, or chasing the butterflies over flowery beds.

And so, albeit Archie had carried his practical joke out to his own satisfaction, if not to that of every one else, this evening, like many others that had come before it, and came after it, passed away pleasantly enough.

It was in the spring of the same year, and during the Easter holidays, that a little London boy came down to reside with his aunt, who lived in one of Archie’s father’s cottages.

Young Harry Brown had been sent to the country for the express purpose of enjoying himself, and set about this business forthwith. He made up to Archie; in fact, he took so many liberties, and talked to him so glibly, and with so little respect, that, although Archie had imbued much of his father’s principles as regards liberalism, he did not half like it.

Perhaps, after all, it was only the boy’s manner, for he had never been to the country at all before, and looked upon every one—Archie included—who did not know London, as jolly green. But Archie did not appreciate it, and, like the traditional worm, he turned, and once again his love for practical joking got the better of his common-sense.

“Teach us somefink,” said Harry one day, turning his white face up. He was older, perhaps, than Archie, but decidedly smaller. “Teach us somefink, and when you comes to Vitechapel to wisit me, I’ll teach you summut. My eye, won’t yer stare!”

The idea of this white-chafted, unwholesome-looking cad, expecting that he, Squire Broadbent’s son, would visit him in Whitechapel! But Archie managed to swallow his wrath and pocket his pride for the time being.

“What shall I teach you, eh? I suppose you know that potatoes don’t grow on trees, nor geese upon gooseberry-bushes?”

“Yes; I know that taters is dug out of the hearth. I’m pretty fly for a young un.”

“Can you ride?”

“No.”

“Well, meet me here to-morrow at the same time, and I’ll bring my ‘Duck.’”

“Look ’ere, Johnnie Raw, ye said ‘ride,’ not ‘swim.’ A duck teaches swimmin’, not ridin’. None o’ yer larks now!”

Next day Archie swept down upon the Cockney in fine form, meaning to impress him.

The Cockney was not much impressed; I fear he was not very impressionable.

“My heye, Johnnie Raw,” he roared, “vere did yer steal the moke?”

“Look you here, young Whitechapel, you’ll have to guard that tongue of yours a little, else communications will be cut. Do you see?”

“It is a donkey, ain’t it, Johnnie?”

“Come on to the field and have a ride.”

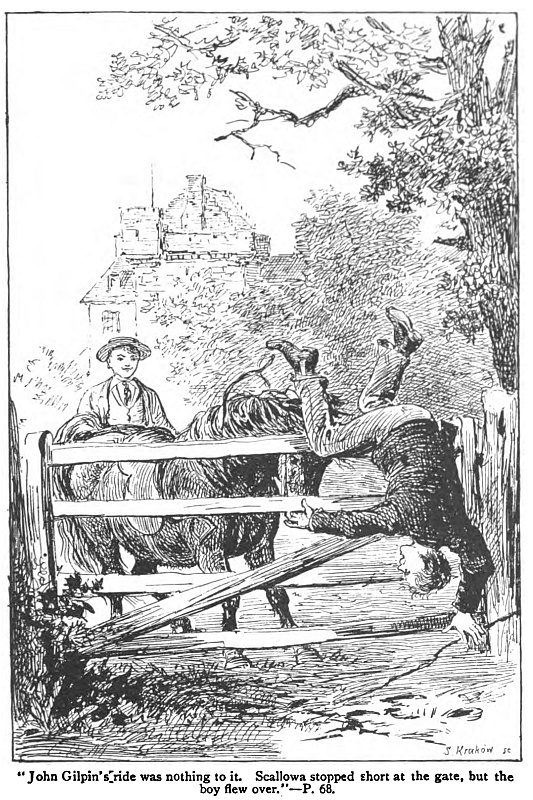

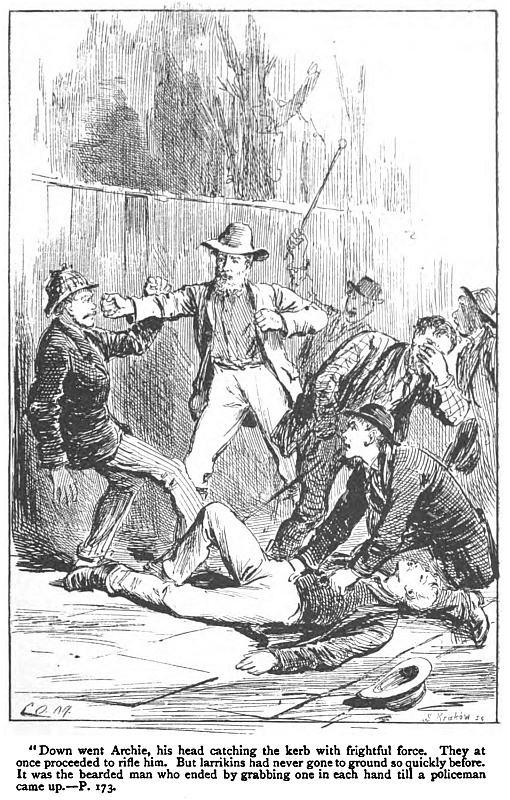

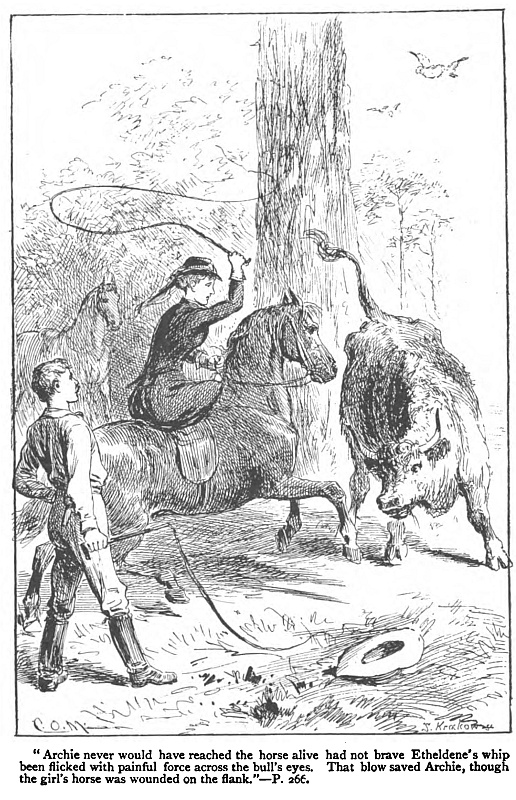

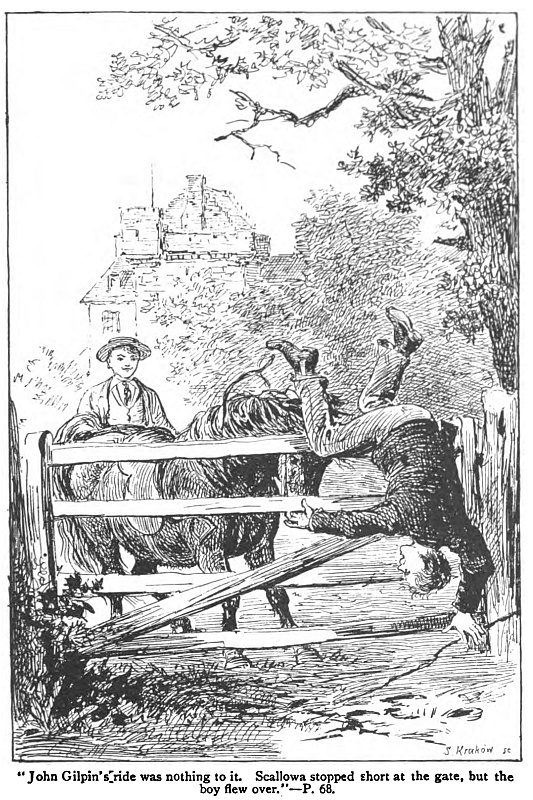

Five minutes afterwards the young Cockney on the “Eider Duck’s” back was tearing along the field at railway speed. John Gilpin’s ride was nothing to it, nor Tam O’Shanter’s on his grey mare, Meg! Both these worthies had stuck to the saddle, but this horseman rode upon the neck of the steed. Scallowa stopped short at the gate, but the boy flew over.

Archie found his friend rubbing himself, and looking very serious, and he felt happier now.

“Call that ’ere donkey a heider duck? H’m? I allers thought heider ducks was soft!

“One to you, Johnnie. I don’t want to ride hany more.”

“What else shall I teach you?”

“Hey?”

“Come, I’ll show you over the farm.”

“Honour bright? No larks!”

“Yes; no larks!”

“Say honour.”

“Honour.”

Young Whitechapel had not very much faith in his guide, however; but he saw more country wonders that day than ever he could have dreamt of; while his strange remarks kept Archie continually laughing.

Next day the two boys went bird-nesting, and really Archie was very mischievous. He showed him a hoody-crow’s nest, which he represented as a green plover’s or lapwing’s; and a blackbird’s nest in a furze-bush, which he told Harry was a magpie’s; and so on, and so forth, till at last he got tired of the cheeky Cockney, and sent him off on a mile walk to a cairn of stones, on which he told him crows sometimes sat and “might have a nest.”

Then Archie threw himself on the moss, took out a book, and began to read. He was just beginning to repent of his conduct to Harry Brown, and meant to go up to him like a man when he returned, and crave his forgiveness.

But somehow, when Harry came back he had so long a face, that wicked Archie burst out laughing, and forgot all about his good resolve.

“What shall I teach you next?” said Archie.

“Draw it mild, Johnnie; it’s ’Arry’s turn. It’s the boy’s turn to teach you summut. Shall we ’ave it hout now wi’ the raw uns? Bunches o’ fives I means. Hey?”

“I really don’t understand you.”

“Ha! ha! ha! I knowed yer was a green ’un, Johnnie. Can yer fight? Hey? ’Cause I’m spoilin’ for a row.”

And Harry Brown threw off his jacket, and began to dance about in terribly knowing attitudes.

“You had better put on your clothes again,” said Archie. “Fight you? Why I could fling you over the fishpond.”

“Ah! I dessay; but flingin’ ain’t fightin’, Johnnie. Come, there’s no getting hout of it. It ain’t the first young haristocrat I’ve frightened; an’ now you’re afraid.”

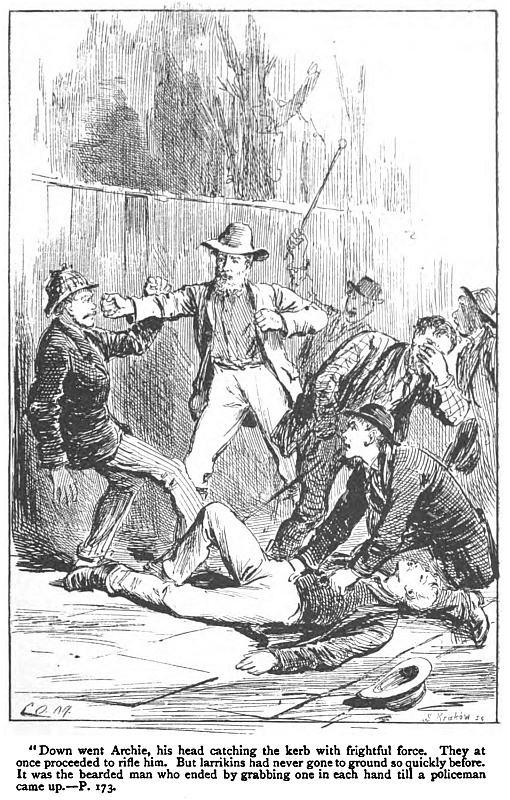

That was enough for Archie. And the next moment the lads were at it.

But Archie had met his match; he went down a dozen times. He remained down the last time.

“It is wonderful,” he said. “I quite admire you. But I’ve had enough; I’m beaten.”

“Spoken like a plucked ’un. Haven’t swallowed yer teeth, hey?”

“No; but I’ll have a horrid black-eye.”

“Raw beef, my boy; raw beef.”

“Well; I confess I’ve caught a tartar.”

“An’ I caught a crab yesterday. Wot about your eider duck? My heye! Johnnie, I ain’t been able to sit down conweniently since. I say, Johnnie?”

“Well.”

“Friends, hey?”

“All right.”

Then the two shook hands, and young Whitechapel said if Archie would buy two pairs of gloves he would show him how it was done. So Archie did, and became an apt pupil in the noble art of self-defence; which may be used at times, but never abused.

However, Archie Broadbent never forgot that lesson in the wood.

Chapter Six.

“Johnnie’s got the Grit in him.”

On the day of his fight with young Harry in the wood, Archie returned home to find both his father and Mr Walton in the drawing-room alone. His father caught the lad by the arm. “Been tumbling again off that pony of yours?”

“No, father, worse. I’m sure I’ve done wrong.” He then told them all about the practical joking, and the finale.

“Well,” said the Squire, “there is only one verdict. What do you say, Walton?”

“Serve him right!”

“Oh, I know that,” said Archie; “but isn’t it lowering our name to keep such company?”

“It isn’t raising our name, nor growing fresh laurels either, for you to play practical jokes on this poor London lad. But as to being in his company, Archie, you may have to be in worse yet. But listen! I want my son to behave as a gentleman, even in low company. Remember that boy, and despise no one, whatever be his rank in life. Now, go and beg your mother’s and sister’s forgiveness for having to appear before them with a black-eye.”

“Archie!” his father called after him, as he was leaving the room.

“Yes, dad?”

“How long do you think it will be before you get into another scrape?”

“I couldn’t say for certain, father. I’m sure I don’t want to get into any. They just seem to come.”

“There’s no doubt about one thing, Mr Broadbent,” said the tutor smiling, when Archie had left.