THE ELIMINATOR; OR, SKELETON KEYS TO SACERDOTAL SECRETS

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: The Eliminator; or, Skeleton Keys to Sacerdotal Secrets

Author: Richard B. Westbrook

Release Date: March 25, 2012 [EBook #39268]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ELIMINATOR; OR, SKELETON KEYS TO SACERDOTAL SECRETS***

Produced by David Widger.

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

THE Eliminator has now been before the public nearly two years. I have seen nothing worthy of the name of criticism respecting it. A few Unitarian ministers have said that Christ must have been a person instead of a personification, for the reason that men could not have conceived of such a perfect character without a living example, and that the great influence exercised by him for so long a time, over so many people, proves him to have been an historic character. These arguments are anticipated and fully answered. (See pp. 283, 284, 306.)

Our Unitarian friends are the greatest idealists upon the globe! They only accept the Gospel biography of Jesus (and we have no other) just so far as the story accords with what they think it ought to be. They deny the immaculate conception and miraculous birth of the Christ, and have very great doubts about his crucifixion and resurrection. Their Christ is purely ideal. The fact is that Christendom has worshipped the literal Jesus for the ideal Christ for nearly twenty centuries, though their conceptions of him have been manifold and contradictory. No wonder that so many intelligent Christian sects in the early ages of the [Pg iv] church utterly denied the existence of Jesus as an historic person. (See pp. 266, 267, 357.) But there is indubitable evidence that this Christ character (called by many Unitarians the “Universal Christ”) was mainly mythical, drawn from the astrological riddles of the older Pagan mythologies.

In fact, almost everything in Christianity seems to have been an afterthought. It is the least original of any of the ten great religions of the world, and the great mistake has been in making almost everything literal which the wise men of ancient times regarded as allegorical. This comes from the priestly attempt to identify the Jewish Jesus with the Oriental Christ Tradition is, in fact, the main foundation of the Christian scheme, and cunning sacerdotalists have done by artifice what history, in fact, has failed to do. But for its moral precepts and its “enthusiasm of humanity,” Christianity would not survive for a single century. The so-called “Apostles’ Creed” (which was not formulated until centuries after the last Apostle slept in the grave), and which is repeated in so many churches every Sunday, has a greater number of historical and theological misstatements than any other writing of the same length now extant!

There is in our day a general disposition to magnify the virtues of the Christ of the New Testament, connected with a proposition to unite all Christians in his leadership. This device will not succeed, because it is as impossible to found a perfect religion upon an imperfect man as it is upon a fallible Book. Lovers of the truth will show that the traditional Christ is not a perfect model. (See Chapter xiii.) There is a most significant sense in which it may be truthfully said: “Never man spake like this man,” as no great moral teacher ever uttered so many things that needed to be revised and explained!

May it not be the fact that both Catholic and Protestant Christians are under a great delusion as to the facts of religion? I think so. I believe so. I well know how difficult it is to explode a delusion that is nearly twenty centuries old, and that is supported by a sacerdotalism of vast wealth and learning, and whose votaries by “this craft have their wealth.”

I nail these Thèses to the church doors of all the Catholics and Protestants in Christendom, and with Martin Luther, at the Diet of Worms, I exclaim, “Here I stand. I cannot move! God help me!” If I am mistaken, then my reason is at fault and all history is a lie! It is said that when Renan died, the Pope inquired whether he had confessed before his de-cease, and upon being told that he had not, replied, “Well, then God will have to save him for his sincerity!” I am ready to be judged on this ground. I sum up my latest conclusions thus: The Jesus of the Gospels is traditional, the Christ of the New Testament is mythical.

WESTBROOK.

1707 Oxford Street,

Philadelphia.

October 1, 1894.

PREFACE

Many things in this book will greatly shock, and even give heartfelt pain to, numerous persons whom I greatly respect. I have a large share of the love of approbation, and naturally desire the good opinion of those with whom I have been associated in a long life. There is no pleasure in the fact that I have to stand quite alone in the eyes of nearly all Christendom. There is no satisfaction in being deemed a disturber of the peace of the great majority of those “professing and calling themselves Christians.” But, at the same time, I must not be indifferent in matters where I believe truth is concerned.

Before I withdrew from the orthodox ministry I used to wonder why God in his gracious providence had not seen fit to so order events as to give us a credible and undoubted history of the incarnation and birth of his Son Jesus Christ, and why that Saviour, who had come to repair the great evils inflicted upon our race by Adam, had never once mentioned that unfortunate fall.

I do not deny that there was a person named Jesus nearly nineteen hundred years ago. I think there were several persons bearing this name and who were contemporaneous, and that several of them were very good men; but that any one of them was such a person as is described in the Gospels I cannot believe. I lay special emphasis on the word such. Admitting for the sake of the argument the real, historical personality of Jesus of Nazareth, he has by the process of idealization become an impersonation, and I have so attempted to make it appear; and I cannot but think that this view is not inconsistent with the most enlightened piety and religious devotion, while this explanation relieves us of many things which are absurd and contradictory.

I desire to explain more fully than appears in the Table of Contents the plan of this book. I first combat the policy of suppression and deception, and insist that the whole truth shall be published, and have shown that sacerdotalism is responsible for the fact that it has not been done. As so-called Christianity is based upon Judaism, I undertake to show the fabulous character of many of the claims of the Jews, disclaiming all intention to asperse the character of Israelites of the present generation.

I thought it proper in this connection to give the substance of an open letter to the Chief-Justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on Moses and the Pentateuch—to which His Honor never responded—showing that the “law of Sinai was not the first of which we have any knowledge,” and that Moses was not “the greatest statesman and lawgiver the world had ever produced,” as the Chief-Justice had affirmed in a lecture before the Law School of the University of Pennsylvania.

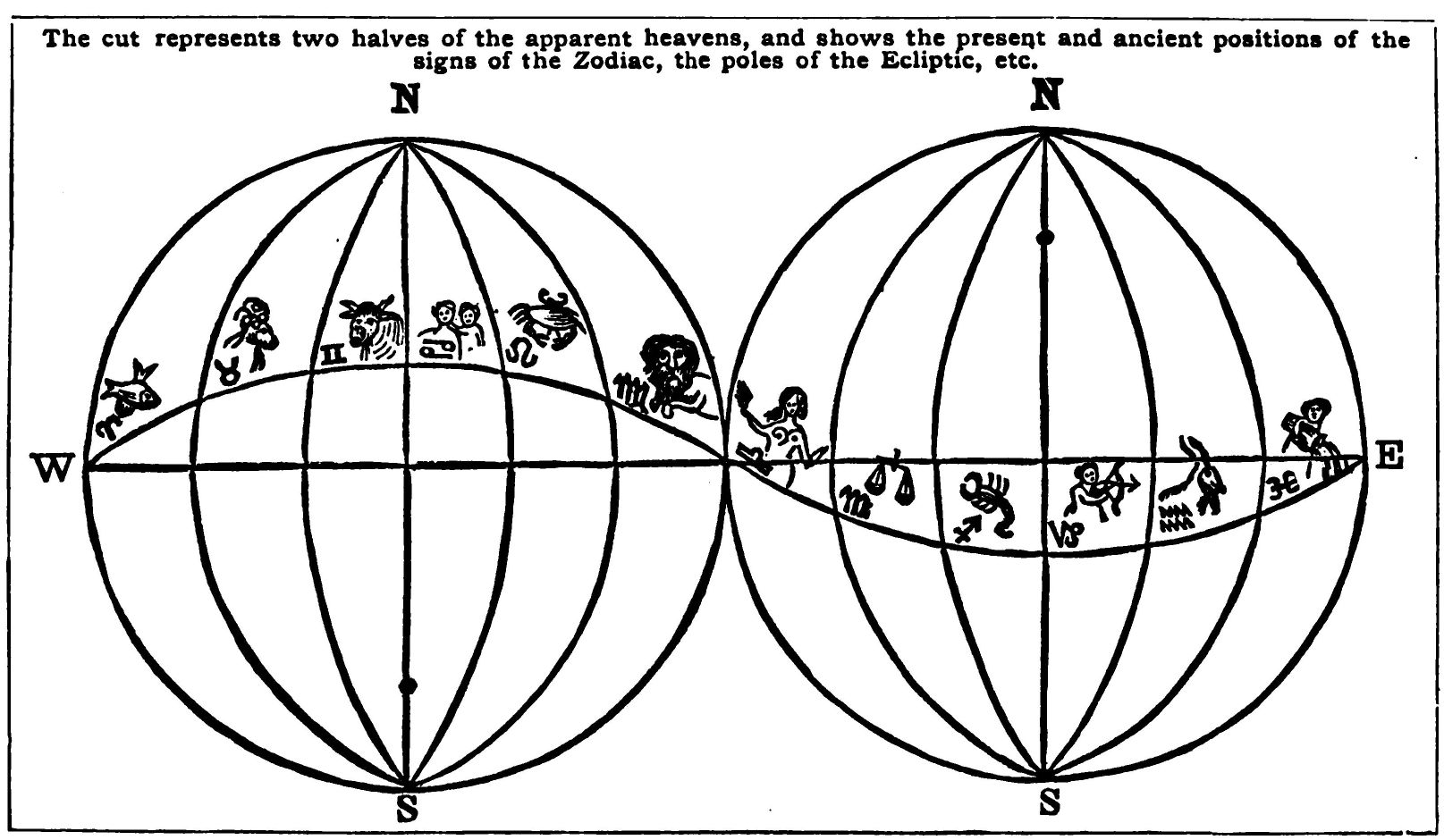

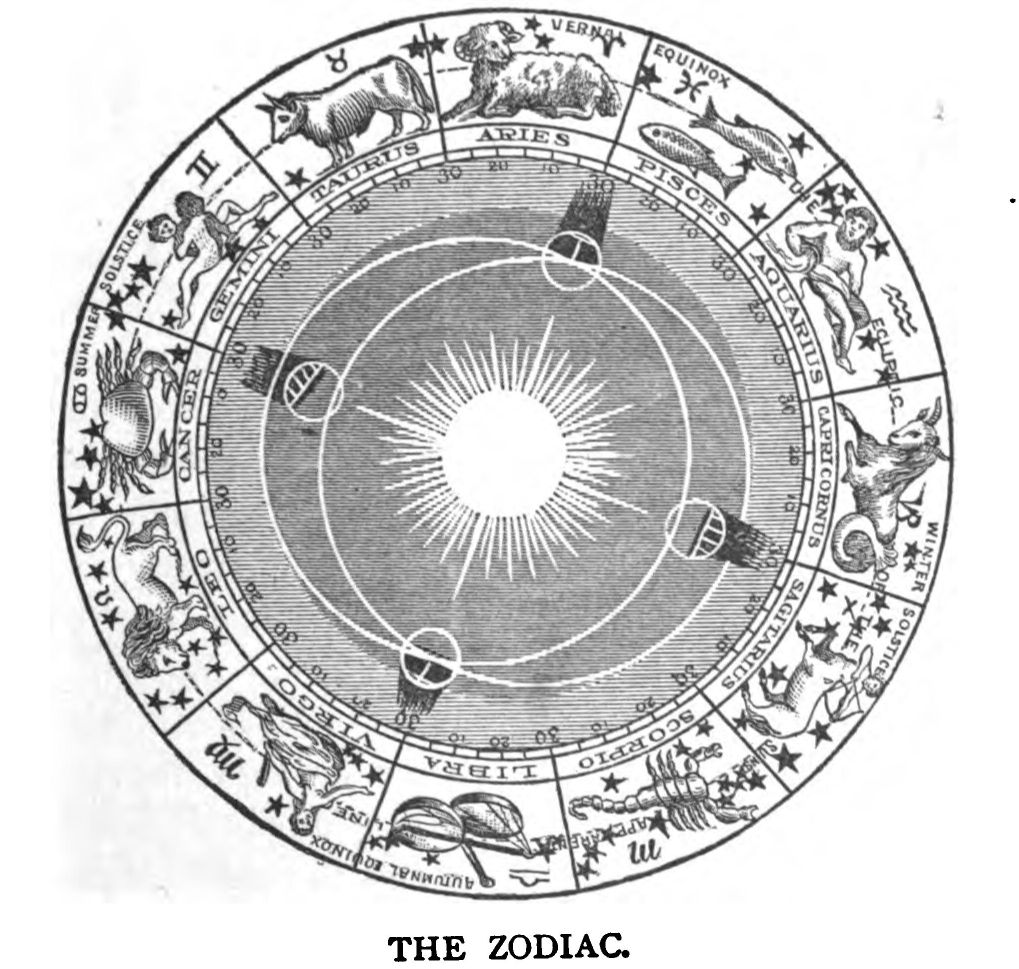

Presenting brief views of the symbolic character of the Old Testament, and showing how “Astral Keys” unlock many Bible stories, I undertake to show that the so-called fall of Adam is a fable, nothing more; and then, as the first Adam is shown to be a myth, I go in search for the “last Adam.” Finding no knowledge of such a person except in the New Testament, I deem it necessary to briefly show the character of this book, that it may be determined how far it should be received as evidence in a matter of so much importance. Then in five chapters, more or less connected, I combat the idea of the historical, or rather traditional, Jesus, and follow with an examination of the evangelical dogma of Blood-Salvation, and close with a very brief summary of the Things that Remain as the foundation of faith.

I do not expect caste clergymen to read this book any farther than is necessary to denounce it. It is their way of meeting questions like those herein discussed. I am prepared to have certain dilettanti sneer-ingly say, “This book is of no critical value.” They are so accustomed to “scholarly essays” which “are poetically sentimental and floridly vague” that they have little respect for anything else. The book is intended for the common people, and not for the professional critics.

I do not expect everybody to agree with me, especially at first. Truth can afford to wait, and in years to come many points that I have made, which are now so startling, will be calmly and intelligently accepted.

There are probably mistakes in the book—mistakes in names, in dates, and perhaps in facts; but these will not affect the main argument. No man knows everything. Until recently it was never suspected by the learned world that The Contemplative Life was not written by Philo nearly nineteen centuries ago, instead of being written by a monk in the third century of the Christian era. Even Macaulay and Bancroft have made mistakes, and so have many other authors of good repute.

I have always tried to preserve a reverent spirit—a genuine respect for true religion and morality. I have always been profoundly religious, and cannot remember the time when I was not devout. But I do not believe that it is ever proper “to do evil that good may come.” In this work I have sought only the truth, in the firm conviction that superstition and falsehood cannot promote a course of right living, which is the object and aim of all true religion.

I have a supreme disregard for literary fame. I do not shrink from being called a compiler or even a plagiarist. There is absolutely very little of real originality in the world. I could have followed the course of many writers and absorbed or assimilated, and thus seemingly made my own what they had written; but I have chosen to quote freely, and so have substantially given the words of many authors of repute, and at the same time saved myself the labor of a re-coining, which does not, after all, deceive the intelligent reader. The books from which I largely quote are mainly voluminous and very expensive, and some of them are out of print. I am indebted to the learned foot-notes of Evan Powell Meredith in his prize essay on The Prophet of Nazareth for several things, and must not fail to acknowledge my obligations to certain living authors for valuable assistance, and especially to my friend Dr. Alexander Wilder, who prepared at my request the substance of Chapter X., The Drama of the Gospels, and who, in my judgment, has few superiors in classical and Oriental literature.

I sympathize with those persons who will complain-ingly exclaim, “You have taken away my Saviour, and I know not where you have laid him.” But suppose that we do not need a Saviour in the evangelical sense? Suppose that man has not fallen, but that the race has been rising these many centuries; and that while we have mainly to save ourselves, all the good and great men of all ages have aided us in the work of salvation by what they have said and done and suffered, so that instead of one savior we really have had many saviors. I think that this view is more reasonable and consoling than the commercial device of what is called the “scheme of redemption,” besides having scientific facts to sustain it.

I have preserved on the title-page some of my college degrees, to indicate my professional studies of theology and law, and not from motives of pedantry.

WESTBROOK.

1707 Oxford Street,

Philadelphia.[pg 9]

CHAPTER I. THE WHOLE TRUTH

“For there is nothing covered that shall not be revealed, neither hid that shall not be known. Therefore, whatsoever ye have spoken in darkness, shall be heard in the light, and that which ye have spoken in the ear, in closets, shall be proclaimed upon the housetops.”—Luke 12: 2, 3.

THE assumption is general that if the faith of the common people should be unsettled as to some things which they have heretofore been taught regarding religion, they would immediately reject all truth, and fall into a most deplorable state of skepticism and infidelity, and that the existing institutions of religion would be destroyed, and public virtue so undermined as to endanger the very foundations of morality and civil government. This is not only the fear of conservative and timid clergymen, but many of our prominent statesmen seem anxious lest the enlightenment of the people in matters in which they have been cruelly deceived should so weaken the restraints of police and governmental authority as to result in universal anarchy and a general disregard of the rights of property, and even of the sacredness of human life.

These foolish fears show a great want of confidence in human nature, and falsely assume that moral character depends mainly upon an unquestioning faith in certain dogmas which, in point of fact, have no necessary connection with it.

The statistics of crime show that a very large majority of those who have been seized by the strong arm of the law as dangerous members of society are those who most heartily believe in those very dogmas of theology which we are warned not to criticise, though we may know them to be accretions of ignorance and superstition, and that some of them have a natural tendency to fetter the essential principles of true religion and that higher code of morality which alone can stand strong under all circumstances. It is safe to affirm that ninety-nine hundredths of the criminal class believe, or profess to believe, in the dogmas of the dominant theology, Romish and Protestant; which are essentially the same.

It is too often forgotten that the very first condition of good government is faith in human nature, confidence in the people. You always excite dishonor and dishonesty by treating men as if you think them all rogues, and as if you expect nothing good from them, but every conceivable evil, only as they may be restrained by the fear of pains and penalties in this life and after death.

One great fundamental mistake of theologians and dogmatic pietists is the baseless assumption that religion is something supernatural, not to say anti-natural; something external to human nature and of foreign origin; something to be received by transfusion as the result or consequence of faith in certain dogmas or the observance of external rites; something bottled up by the Church, like rare and precious medicines in an apothecary-shop, to be dealt out to those who are willing to follow priestly prescriptions and pay the required price.

The fact is, churches and scriptures and dogmas are the outcome of that religious element which is inherent in human nature. It cannot be too often or too strongly urged that the religious principle is innate and ineradicable in mankind, and that you might as well try to destroy man’s love of the beautiful, his desire for knowledge, his love of home and kindred, or even his appetite for food, as to try to destroy it. It is as natural to feel the want of religion as it is to be hungry. You cannot^ destroy the foundations of religion. They rest in *nature and antedate all creeds and churches, and will survive them.

Even Professor Tyndall says: “The facts of religious feeling are to me as certain as the facts of physics.”

... “The world will have religion of some kind.”... “You who have escaped from these religions into the high and dry light of intellect may deride them, but in doing so you deride accidents of form merely, and fail to touch the immovable basis of the religious sentiment in the nature of man. To yield this sentiment reasonable satisfaction is the problem of problems at this hour.”

Renan also writes thus: “All the symbols which serve to give shape to the religious sentiment are imperfect, and their fate is to be one after another rejected. But nothing is more remote from the truth than the dream of those who seek to imagine a perfected humanity without religion.”... “Devotion is as natural as egoism to a true-born man. The organization of devotion is religion. Let no one hope, therefore, to dispense with religion or religious associations. Each progression of modern society will render this want more imperious.”

We use the word religion as it was used by Cicero, in the sense of scruple, implying the consciousness of a natural obligation wholly irrespective of what one may believe concerning the gods. Religion in its true meaning is the great fact of duty, of oughtness, consisting in an honest and persistent effort to realize ideal excellence and to transform it into actual character and practical life. Religion as a spirit and a life is objected to by none, but is admired and commended by all. It is superstition, bigotry, credulity, and dogma that are detestable. The religious instinct has been perverted, turned into wrong channels, made subservient to priestcraft and kingcraft, but its basic principle remains for ever firm. If it could have been destroyed, the machinations of priests would have annihilated it long ago. Give yourselves no anxiety about the corner-stone of religion, but look well to the rotten superstructures that have been reared upon it. Its professed friends are often its real enemies. It is the false prophet who is afraid to have his oracles subjected to tests of reason and history. It is the evil-doer who is afraid of the light, the conscious thief who objects to being searched. An honest man would say, “Let the truth be published, though the heavens fell.”

The whole truth should be published, as a matter of common honesty, if nothing more. We have no moral right to conceal the truth, any more than we have to proclaim falsehood. He who deliberately does the one will not hesitate long about doing the other. And this is one of the most serious aspects of this subject. He who can bring himself to practise deceit regarding religion will soon be a villain at heart, even if worldly prudence is strong enough to keep him out of the penitentiary.

As a rule, the unfaithful teacher inflicts a greater evil upon his own soul than upon his unsuspecting dupe. The deceiver is sure to be overtaken by his own deceit. Mean men become more mean, and liars come to believe their own oft-repeated falsehoods. This principle may in part account for the fact that in all ages dishonest, mercenary, designing priests have been most corrupt citizens and ready tools in the hands of tyrants to oppress and enslave the people.

Every deceptive act blunts the moral sense, defiles and sears the conscience, until at last the hypocrite degenerates into a slimy, subtle human serpent that always crawls upon its belly and eats dust. Secretiveness and deceitfulness become a second nature, and show themselves continually even in the ordinary affairs of life. The reflex influence of deception upon the deceiver himself is its most bitter condemnation.

But modern preachers have a way of justifying their evasions and prevarications by saying that even Jesus himself withheld from his own disciples some things, for the reason that they were “not able to bear them,” quite overlooking the fact that he is also reported to have said, “When the Spirit of truth has come, he will teach you all things,” and that other passage (Luke 12: 2), where Jesus is represented as saying, “For there is nothing covered that shall not be revealed, neither hid that shall not be known. Therefore, whatsoever ye have spoken in darkness, shall be heard in the light, and that which ye have spoken in the ear, in closets, shall be proclaimed upon the housetops.”

If after eighteen hundred years of Christian teaching the time has not yet come to proclaim the whole truth, it is not likely to come for many ages in the future. If religion is a mystery too great to be comprehended, too sacred for reverent but untrammelled investigation, something that can only exist with a blind, unreasoning credulity and the utter stultification of the natural faculties of a true manhood, then religion is not worth what it costs and should be exposed as a delusion and a snare.

The time for the religious Kabala has passed, and ambiguities, concealments, and evasions are no longer to be tolerated. Martin Luther builded better than he knew when he proclaimed the right of private judgment in matters of religion. It has taken two hundred years for this fundamental principle to become thoroughly accepted by the people; but so firmly is it now established that bigoted ecclesiastics might as well attempt to resist the trend of an earthquake, stop the rising of the sun, and turn the light of noonday into the darkness of midnight as to attempt to arrest the progress of a true religious rationalism. The mad ravings of fanatics will have no more influence than the pope’s bull had on the comet. Learning is no longer monopolized by a few monks and ministers. For every five clergymen who are abreast with the times, the progress of modern thought, and the conclusions of science, there are fifty laymen who are familiar with the writings of Humboldt, Darwin, Huxley, Spencer, Tyndall, and scores of other scientists, to whom the world is more indebted for true progress than to all the lazy monks and muttering priests who have lived since the world began. The fact is, the old delusion that men must look to the sacerdotal class exclusively, or even mainly, for religious truth, has been for ever banished from the minds of intelligent men. The literature of the day is full of free thought and downright rationalism, and even the secular newspaper is a missionary of religious progress and reform, and brings stirring messages of intellectual progress every day to our breakfast-tables. The world moves, and those who attempt to stop it are sure to be crushed.

The pretence that anything is too sacred for investigation and publication will not stand the light of this wide-awake nineteenth century.

It is often said that the common people are not ready for the whole truth. In 1873, Dr. J. G. Holland, then editor of Scribner’s Monthly, wrote to Dr. Augustus Blauvelt declining to publish an article on “The Divine and Infallible Inspiration of the Bible,” and added, “I believe you are right. I should like to speak your words to the world; but if I do speak them it will pretty certainly cost me my connection with the magazine. This sacrifice I am willing to make if duty requires it. I am afraid of nothing but doing injury to the cause I love.... In short, you see that I sincerely doubt whether the Christian world is ready for this article.... Instead of the theologians the people would howl.... I cannot yet carry my audience in such a revolution. Perhaps I shall be able to do so by and by, but as I look at it to-day it seems impossible.... My dear friend, I believe in you. You are in advance of your time. You have great benefits in your hands for your time. You are free and true. And I mourn sadly and in genuine distress that I cannot speak your words with a tongue which all my fellow-Christians can hear. They will not hear them yet. They will some time....”

Dr. Holland has passed away and cannot reply to criticism. Let us be kind and charitable. He intended to be right, but he was mistaken. The people do not howl when the truth is published, even though their prejudices may be aroused; and no tedious preparation is now necessary to be able to hear the whole truth. The masses of the people are hungry for knowledge, and it is high time that they be honestly fed. They now more than half suspect that they have been deceived by those some of whom they have educated by their charities and liberally paid to teach them the truth. When, in 1875, Scribner’s Monthly did publish Dr. Blauvelt’s articles on “Modern Skepticism,” it was not the people that “howled.” It was the clergy. Some of them demanded a new editor; others warned the people from the pulpit not to patronize Scribner; and one distinguished man declared that the magazine must be “stamped out,” and at once organized a most powerful ecclesiastical combination against the freedom of the press; and yet the North American Review and other similar magazines are today doing more to settle long-mooted religious questions than all the pulpits in Christendom; and the people do not howl. No respectable enterprising publisher now hesitates to publish a book of real merit, however much its doctrines may differ from the dominant faiths. The masses of the people are determined to know all that can be known of the history, philosophy, and principles of religion; and the greater the effort to conceal and suppress the truth the stronger will be the demand for its full and undisguised proclamation.

That there is a general drifting away from the old formulas of religious doctrine everybody knows, and yet there is more practical religion in the world to-day than in any previous age. It does not consist in fastings and attendance upon ecclesiastical rites and ordinances; but it takes the form of universal education, of providing homes for friendless infancy and old age, of the prevention of cruelty to children and even to brute animals, of the more rational and humane treatment of lunatics, paupers, and criminals, ameliorating the miseries of prisons and hospitals,—in short, of elevating and improving the condition of universal humanity. These truly religious works do not depend upon any particular statement of religious belief, for all sects and persons of no sect are equally engaged in them.

Charities would not cease if all creeds should be abandoned or should be so revised as not to be recognized by the disciples of Calvin and Wesley, and if every priest in the land should henceforth give up the mummeries and puerilities of the Dark Ages.

Religion, as the “enthusiasm of humanity,” the cultivation of all the virtues, and the practice of the highest morality growing out of the inalienable rights of man in all the relations of life, is a fixed fact. It is a natural endowment, coeval with humanity in its development and progress, and is as absolutely indestructible as manhood itself.

So far from being true is the assumption that religion would be imperilled by the exposure of the false dogmas of theology and the heathenish rites and superstitious ceremonies of ecclesiasticism, it is clear to many minds that the myths of dogmatic theology and the absurdities of primitive ages are the chief obstacles in the way of the free course of true religion; and it may safely be affirmed that the distinguishing dogmas of the dominant theology, Catholic and Protestant, as will hereafter be shown, are essentially demoralizing and logically tend to undermine and corrupt public virtue. It is not intended to affirm that churches and theologians do no good and that their entire influence is bad. They teach much that is humane in principle and moral in practice, and so do good for society. Nevertheless, it is true that much of the rotten morality of the times can be philosophically traced to the influence of a false theology. The main dogmas of Romish and orthodox Protestant creeds are false, and it is absurd to suppose that a pure system of public virtue can be founded upon ignorance, superstition, and falsehood.

But, after all, we are asked, Does it make any odds what one believes if he is only sincere in his faith?

The obvious answer is, that the more sincerely you believe a lie the more dangerous is your faith. The more trustfully you build upon a sandy foundation the sooner and greater will be the fall and ruin of the superstructure. The more implicitly you confide in a dishonest partner or agent the more successful will be his robbery. There is no safety in error and falsehood. The Westminster divines well said, “Truth is in order to righteousness.” There can be no true righteousness inherent in a system of superstition and falsehood. The failure of the Church to reach the masses and to establish a condition of public honesty superior to the ancient heathen morality shows that there must be some serious defect in its methods.

But the crushing objection to theological agitation and free discussion is the common one that “it is unwise to unsettle and destroy the faith of the people in the dominant theology unless there is something better to offer them as a substitute.”

There is something better. Truth is always better and safer than falsehood. In the discussions which are to follow an attempt will be made to show that there is a natural religion which accords with enlightened reason, and which cannot fail to furnish a firm scientific foundation for the highest morality. The common saying, that “it is better to have a false religion than no religion,” contains two groundless assumptions—viz. that it is possible for a man to have no religion, and that that which is false may be dignified with the name religion. It is about time that things should be called by their right names, and that superstition and falsehood should not be deemed necessary to public morality.

For a religion (so called) of superstition and falsehood there must be a religion of natural science*that cannot be overthrown, and which cannot fail to make its way among men as knowledge shall increase and the principles of true religious philosophy shall be [pg 21] better understood. We should not be frightened at the cowardly cry of “destructive criticism.” We *must pull down before we can reconstruct.

CONCLUSIONS.

To imitate the example of the early Christian Fathers in fraud, falsehood, and forgery for the promotion of religion is a policy that is too shocking to the moral sense of civilized men everywhere to be tolerated. To withhold or suppress the truth is a crime against humanity and contrary to the spirit of this age; and those who do it are the enemies of progress and unworthy to be recognized as the authoritative teachers of the world.

Those who publish that which is false or suppress what is true not only do a great wrong to the people, but, if possible, do a greater wrong to their own souls, and must suffer the consequences. They must have an awful reckoning with eternal, retributive justice.

It is a most egregious mistake to suppose that the people cannot be trusted with the whole truth—that their sense of right is so dull and flimsy that on the slightest discovery of the errors in which they have been instructed from infancy they would lose confidence in all truth and rightfulness and rush riotously to ruin. If the people must be hoodwinked for ever, then the distinguishing principle of the Protestant Reformation and the basic principles of our American Declaration of Independence and republican government are false and delusive, and we should return to mediæval times and to feudal and autocratic government in Church and State.

It is high time that men should see that dogma is not religion; that blind faith is more to be feared than rational skepticism and scientific investigation; that whatever is opposed to reason and science in theology can be spared, not only without any loss, but greatly to the advantage of true religion and sound morality. All the religion that is worth having is natural and rational, and corresponds with the facts of the universe as they are demonstrated by the crucibles of science and the inductions of a sound philosophy. The principal moral obligations of men grow out of their relations to each other in life, and nothing can be more complete than the Golden Rule, emphasized in the Sermon on the Mount, but as clearly taught in the Jewish Babylonian Talmud, and in the twenty-fourth Maxim of the Chinese philosopher Confucius, and many others centuries before the Christian era.

Instead of loading down religion with Oriental myths and fables, instead of a gorgeous ritualism and surpliced priests, borrowed literally from the ancient paganism, instead of dogmas and creeds and unquestioning faith and blind submission to ecclesiastical dictation and rule, we want sound moral instruction in the great fundamental truths of nature and of science, which will always be found to strengthen and confirm the principles of true religion. These are the sources from which to gain light. We want less creed and more ethical culture, less profession and paraphernalia in religious worship and more practical philosophy and common sense.

The man who in scientific matters would make false representations and conceal the real truth would be deemed an impostor, and the time has come when hypocrites and cowards in theology should be made to feel their degradation and be forced into an open abandonment of “ways that are dark and tricks that are vain.” If we would scorn delusions in natural philosophy, if we would correct errors in oceanic charts, astronomical diagrams, and geographical maps, why should we hesitate to correct the most egregious blunders regarding those things which are infinitely more important? Can we with any proper sense of propriety and right connive at falsehood and uphold and strengthen it by our silence and cowardly negligence in failing to expose it? Are not all delusions debasing and opposed to the progress of truth and the elevation of mankind? In all the departments of human knowledge religion and morality are most imperative in their demands for pure and unadulterated truth; and he who does not recognize this fact sins grievously against his own soul, against the human family, and against the truth and its eternal Author, the God of all truth.

Finally, let it not be overlooked that it will not, for many reasons, be possible much longer to keep the people in ignorance, and to palm off upon them myths for veritable history and a system of theology plainly at variance with the conclusions of science, the facts of history, and the spiritual and moral consciousness of every true and well-developed man. The schoolmaster is abroad, and the spirit of fearless investigation is in the air, and men will, sooner or later, find out what is true; and when they come to understand how they have been imposed upon by their cowardly teachers, a fearful reaction will be the result; and woe to the hypocrite and time-server when that time comes! It is therefore not only good principle, but good policy, to tell the whole truth now. The following copy of a book-notice well describes the prevalent policy regarding matters of faith:

“A theory of religious philosophy which is much commoner among us than most of us think, but which has never been expressed so fully or so attractively as in the story of Marius.

“‘Submit,’ it seems to say, ‘to the religious order about you, accept the common beliefs, or at least behave as if you accepted them, and live habitually in the atmosphere of feeling and sensation which they have engendered and still engender; surrender your feeling while still maintaining the intellectual citadel intact; pray, weep, dream with the majority while you think with the elect; only so will you obtain from life all it has to give, its most delicate flavor, its subtlest aroma.’” Against such a sham the writer heartily protests, as against the villainous maxim, quoted from memory, accredited to Aristotle: “Think with the sages and philosophers, but talk like the common people.” Come what may, let us cease to profess what we have ceased to believe.

“The two learned people of the village,” says Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, telling of his fanciful Arrowhead Village, “were the rector and the doctor. These two worthies kept up the old controversy between the professions which grows out of the fact that one studies nature from below upward, and the other from above downward. The rector maintained that physicians contracted a squint which turns their eyes inwardly, while the muscles which roll their eyes upward become palsied. The doctor retorted that theological students developed a third eyelid—the nictitating membrane, which is so well known in birds, and which serves to shut out, not all light, but all the light they do not want.”

The Presbyterians have provided for a revision of their creed, though they have stultified themselves by certain restrictions, shutting out the light they do not want! Let us hope that the time will soon come when men will be honest enough and brave enough to follow the truth wherever it may lead. Let there be perfect veracity above all things, more especially in matters of religion. It is not a question of courtesies which deceive no one. To profess what is not believed is immoral. Immorality and untruth can never lead to morality and virtue; all language which conveys untruth, either in substance or appearance, should be amended so that words can be understood in their recognized meanings, without equivocal explanations or affirmations. Let historic facts have their true explanation.

CHAPTER II. SACERDOTALISM IMPEACHED

“The heads thereof judge for reward, and the priests thereof teach for hire, and the prophets thereof divine for money.”—Micah 3: 11.

“Put me, I pray thee, into one of the priests’ offices, that I may eat a piece of bread.”—1 Sam. 2: 36.

THE cognomens priest, prophet, presbyter, preacher, parson, and pastor have certain things in common, and these titles may therefore be used interchangeably.

As far back as history extends, the office or order now represented by the clerical profession existed. It was as common among pagan tribes in the remotest periods as among Jews and Christians in more modern times. Service done to the gods by the few in behalf of the many is the primary idea of the priestly function. It has always and everywhere been the profession and prerogative of the priests to pretend to approach nearest to the gods and to propitiate them; on account of which they have always been supposed to have special influence with the reigning deity and to be the authorized expounders and interpreters of the divine oracles. The priesthood has always been a caste, a “holy order;” and it was no less so among ancient Jews than among modern Christians. In all churches clergymen ex-officio exercise certain sacred prerogatives. They occupy select seats in every sanctuary. They lead in every act of worship. They preside over every sacred ceremony. They exclusively administer the ordinances of religion. They baptize the children and give or withhold the “Holy Communion.” They celebrate our marriages, visit our sick, and conduct our funerals. In Romish churches and in some of our Protestant churches they pretend to pronounce “absolution” and to seal the postulant for the heavenly rest. It is not necessary, now and here, to speak of the evil influence that these pretensions exert upon the common people, nor of the light in which intelligent, thinking women and men commonly regard them; but it is appropriate to note the reflex influence which such assumptions have upon the clergy themselves, disqualifying them for such rational presentation of doctrinal truth as their hearers have a right to expect.

The pride of his order makes it humiliating for the priest to admit that what he does not know is worth knowing. Claiming to be the authorized expounder of God’s will, how can he admit that he can possibly be in error in any matter relating to religion? In view of the high pretensions of his order, founded, as he claims, upon a plenarily-inspired and infallible book-revelation, and he professing to be specially called and sanctified by God himself as his representative, it would be ecclesiastical treason to admit, even by implication, that he is not in possession of all truth. Regarding his creed as a finality, his mind becomes narrow, circumscribed, and unprogressive. He was taught from childhood that “to doubt is to be damned,” and through all his novitiate he was warned against being unsettled by the delusions of reason and the wiles of infidelity. His professional education has been narrow, one-sided, sectarian. He has seldom, if ever, read anything outside of his own denominational literature, and has heard little from anybody but his own theological professors and associates. He suspects that Humboldt, Spencer, Huxley, and Tyndall are all infidels, and that the sum and substance of Evolution, as taught by Darwin, is that man is the lineal descendant of the monkey.

Some persons think that ministers are often selected from among weaklings in the family fold. However, this may be, the absorption of the “holy-orders” idea, and the natural self-assurance and self-satisfaction that belong to a caste profession, render delusive the hope that anything original can ever come from such a source. Whether weak at first or not, the habits of thought and the peculiar training of young ecclesiastics are almost sure to dwarf them intellectually for life. The theological student has become the butt in wide-awake society everywhere, and his appearance in public is the occasion for jests and ridicule over his sanctimonious vanity and silly pride. The extreme clerical costume which he is sure to assume excites the disgust of sensible people, though he may march through the street and up the aisle with the regulation step of the “order,” and suppose himself to be the object of reverent admiration on the part of all beholders. No wonder that the churches complain that few young men of ability enter the ministry in these modern times.

The priestly office has always been deemed one of great influence, so that ancient kings were accustomed to assume it. This was true of the kings of ancient Egypt, and the practice was kept up among the Greeks and Romans. Even Constantine, the first Christian emperor (so called), continued to exercise the function of a pagan priest after his professed conversion to Christianity, and he was not initiated into the Christian Church by baptism until just before his death. One excommunicated king lay for three days and nights in the snow in the courtyard before the Pope would grant him an audience! The “Pontifex-Maximus” idea of the Roman emperors was the real foundation of the “temporal power” claimed by the bishops of Rome. Kingcraft and priestcraft have always been in close alliance. When the king was not a priest he always used the priest; and the priest has generally been willing to be used on the side of the king as against the people when liberally subsidized by the reigning potentate. Moreover, priestcraft has always been ambitious for power, and sometimes has been so influential as to make the monarch subservient to the monk. More than one proud crown has been humbly removed in token of submission to priestly authority, and powerful sovereigns have been obliged to submit to the most menial exactions and humiliations at ecclesiastical mandates. The priestly rôle has always been to utilize the religious sentiment for the subjection of the credulous to the arbitrary influence of the caste or order.

Priestcraft never could afford to have a conscience, so admitted, and therefore it has not shrunk from the commission of any crime that could augment its dominion. Its greatest success has been in the work of demoralization. It has always been the corrupter of religion. The ignorance and superstition of the people and the perversions of the religious sentiment, innate in man, have been the stock in trade of the craft in all ages, and are to-day.

It will be shown later how the whole system of dogmatic theology, Romish and Protestant (for the system is the same), has been formed so as to aggrandize the priest, perpetuate his power, and hold the masses in strict subjection. This is a simple matter of fact. History is philosophy teaching by example, and often repeats itself, and it seldom gives an example of a priestly caste or “holy” order of men leading in a great practical reform. The dominant priestly idea is to protect the interests of the order, not to promote the welfare of the people.

In view of these principles and facts, and others which might be presented, it is reasonable to conclude that we cannot expect the whole living, unadulterated truth, even if they had it, from the professional clergy. The caste idea renders it essentially unnatural and philosophically impossible.

But there are other potent reasons why such expectation is vain. All Christendom is covered with numerous sects in the form of ecclesiastical judicatories, each claiming to be the true exponent of all religious truth. The Romish Church is pre-eminently priestly and autocratic. The priesthood is the Church, and the people only belong to the Church; that is, belong to the priesthood, and that, too, in a stronger sense than at first seems to attach to the word belong. Then the priesthood itself is subdivided into castes.:

“Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em, And little fleas have lesser fleas; and so—ad infinitum”

When Patrick J. Ryan was installed Archbishop in Philadelphia, an office conferred by a foreign potentate, our own city newspapers in flaming headlines called it “The Enthronement of a Priest!” And so it was. He sat upon a throne and received the honors of a prince. He is called “His Grace,” and wears the royal purple in the public streets. Bishops are higher than the “inferior clergy,” and the priest, presbyter, or elder is of a higher caste than the deacon, and all are higher and more holy than the people. All ministers exercise functions which would be deemed sacrilege in a layman. The same odious spirit of caste prevails in fact, if not so prominently in form, in all orthodox denominations, especially as to the distinction between the clergy and the laity. Even Quakers have higher seats for “recommended ministers.”

Moreover, priests have laid down creeds containing certain affirmations and denials which are called “Articles of Religion,” to which all students of divinity and candidates for holy orders must subscribe before they can be initiated into the sacred arcana.

The professor in the theological seminary, who perhaps was selected for the chair quite as much for his conservatism as for his learning, has taken a pledge, if not an oath, that he will teach the young aspirant for ecclesiastical honors nothing at variance with the standards of his denomination; which covenant he is very sure to keep (having other professors and aspirants for professorships to watch him) in full view of the penalty of dismission from his chair and consequent ecclesiastical degradation. The very last place on this earth where one might expect original research, thorough investigation, and fearless proclamation of the whole truth is in a theological school. A horse in a bark-mill becomes blind in consequence of going round and round in the same circular path; and the theological professor in his treadmill cannot fail to become purblind as regards all new truth.

What can be expected from the graduates of such seminaries?

The theological novitiate sits with trembling reverence at the feet of the venerable theological Gamaliel. From his sanctified lips he is to learn all wisdom. Without his approbation he cannot receive the coveted diploma. Without his recommendation he will not be likely to receive an early call to a desirable parish.

The student is obliged to find in the Bible just what his Church requires, and nothing more and nothing less. In order to be admitted into the clerical caste and have holy hands laid upon his youthful head he must believe or profess to believe, ipsissima verba, just what the “Confession” and “Catechism” contain. The Rev. Dr. Samuel Miller once said in a sort of confidential undertone, “What is the use of examining candidates for the ministry at all as to what they believe? The fact that they apply for admission shows that they intend to answer all questions as we expect them to answer; else, they very well know, we would not admit them.”

The ecclesiastical system is emphatically an iron-bedstead system. If a candidate is too long, it cuts him shorter; and if too short, it stretches him. He must be made to fit. Then, after “ordination” or “consecration,” the new-fledged theologian enters upon his public work so pressed by the cares of his charge and the social and professional demands upon his time that he finds it impossible to prepare a lecture and two original sermons a week; so he falls back upon the “notes” he took from the lips of his “old professor” in the divinity school, or upon some of those numerous “skeletons” and “sketches” of sermons expressly published for the “aid” of busy young ministers; and he gives to “his people” a dish of theological hash, if not of re-hash, instead of pouring out his own living words that should breathe and thoughts that should burn.

Hence it is easy to see why one scarcely ever gets a fresh, living truth from the pulpit. It is almost always the same old, old story of commonplace fossils that the wide-awake world has outgrown long ago, and that modern science has fearlessly consigned to the “bats and the moles” of the Dark Ages. No wonder the pulpit platitudes fail to attract the masses of earnest men, especially in our great cities.

Then if a clergyman should discover, after years of thought and study, that he has been in error in some matters, and that a pure rational interpretation of the Bible is possible, and he really feels that the creeds, as well as the Scriptures, need revising, what can he do? If he lets his new light shine, he will share the fate of Colenso, Robertson Smith, Augustus Blauvelt, Professor Woodrow, and scores of others. He knows that heresy-hunters are on the scent of his track. The mad-dog cry of Heretic would be as fatal as a sharp shot from the ecclesiastical rifle. Proscription, degradation, ostracism, stare him in the face. Few men who have the esprit de corps of ecclesiasticism and a reasonable regard for personal comfort and preferment are heroic enough to face the social exclusion, financial ruin, and beggary for themselves and families which are almost sure to follow a trial and condemnation for heresy. If the newly-enlightened minister escapes the inquisition of a heresy trial by declaring himself independent, he has a gauntlet to run in which many poisoned arrows will be sure to pierce his quivering spirit. It is true that some sects have no written creed and no trials for heresy; but even among them there is an implied standard of what is “regular,” and more than one grand soul knows by a sorrowful experience, what it is to belong to the “left wing” of the Liberal army, and to follow the “spirit of truth” outside of the implied creed.

Another reason why the whole truth cannot be expected from the regular clergy is, the influence of their pecuniary dependence upon those to whom they minister. The Jews have always been great borrowers and imitators. It was quite natural that they should adopt the “price-current list” of the ancient Phœnicians, whose priests not only exacted the tribute of “first-fruits,” but a fee in kind of each sacrifice. Then the judicial functions exercised by Jewish priests became a fruitful source of revenue, as the fines for certain offences were paid to the priests (2 Kings 12: 16; Hosea 4: 8; Amos 2: 8). According to 2 Sam. 8: 18 and 2 Bangs 10: 11, also 12: 2, the priests of the royal sanctuaries became the grandees of the realm, while the petty priests were generally poor enough—just as is well known to be the case among the Christian clergy of to-day, some receiving a salary of twenty-five thousand dollars and more per annum, while many of the “inferior clergy” hardly average two hundred and fifty dollars a year.

That the Christian clerical profession was borrowed from the Jews, just as the latter copied it from the heathen, is evident from the fact that Paul, while refusing for himself pecuniary support, preferring to “work with his own hands” (weaving tent-cloth), “living in his own hired house,” nevertheless defended the principle of ministerial support, mainly on the ground of the Mosaic law (Deut. 25: 4), “Thou shalt not muzzle the ox when he treadeth out the corn” (1 Cor. 9: 9; 1 Tim. 5: 18). It is a striking illustration of the inconsistency of the modern clergy that they quote, in reference to a salaried ministry, the words ascribed to Jesus (Matt. 10: 10), “The workman is worthy of his meat,” or, as it is rendered in Luke 10: 7, “The laborer is worthy of his hire,” very conveniently forgetting to quote the connecting words requiring them to “provide neither gold nor silver nor brass in their purse, nor scrip for their journey, neither two coats, neither shoes, nor yet staves,” but to enter unceremoniously into any house, accepting any proffered hospitality, “eating such things as might be set before them.” The fact is, the first disciples of Jesus, according to our Gospels, were mendicant monks, leading lives of asceticism and poverty. There is no evidence that one of them ever received a salary; they made themselves entirely dependent on public charity and hospitality. The idea of a “church living” or “beneficed clergy” or a salaried ministry never entered into the mind of Him of whom it is said he “had not where to lay his head.”

It is enough for the present argument to emphasize the point that, in the very nature of things, it is not reasonable to expect the whole truth from a salaried ministry. Those who have a large salary naturally desire to retain it; those who have small and insufficient salaries naturally desire to have them increased.

This can only be done by carefully preserving a good orthodox standing according to the sectarian shibboleth, and in pleasing the people who rent the pews or who dole out their penurious subscriptions for “the support of the gospel.” High-salaried ministers are most likely to be proud, arrogant, bigoted, sectarian. Starveling ministers become broken in spirit, fawning, and crouching, and they generally have an unconscious expression of appeal for help, of importunity and expectancy, stamped upon their faces. The millstone of pecuniary dependence hangs so heavily about their necks that they seldom hold up their heads like men, and they can never utter a new truth or a startling sentiment without pausing to consider what effect it may have on the bread and butter of a dependent and generally numerous family. Ministers with high salaries are almost sure to be spoiled, and those with low ones are sure to be stultified and dwarfed intellectually and morally; so that we cannot depend upon either class for the highest and latest truths. Those who have a “living,” provided in a State Church, and those who depend upon voluntary contributions from the people, are alike manacled and handicapped. We must look elsewhere than to the modern pulpit for that truth which alone can give freedom and true manliness. Perfect indifference as to ecclesiastical standing, backed by pecuniary independence, is an essential condition for untrammelled investigation and the fearless proclamation of the whole truth.

It was noticed in the recent convention of scientists in this city (the American Association) that it was the salaried professors in Church colleges who professed to find no conflict between Geology and Genesis. It will always be so until the ecclesiastical tyranny is greatly weakened or destroyed, and men can utter their boldest thoughts without fear or favor, and when teachers can afford to have a conscience by making themselves free from Church control and menial dependence upon those to whom they minister for the necessaries of a mere livelihood. Science itself has made progress only as it has been fearless of priestly maledictions; and when it shall throw off the incubus of Church patronage it will astonish the world in showing the eternal antagonisms between the dogmas of the dominant theology and the essential truths of natural religion and morality.

CONCLUSIONS.

The following conclusions follow from what has been said:

The clerical fraternity claims to be more than a mere profession. It is essentially a caste, a “holy order,” borrowed from the ancient paganism, but somewhat modified by Judaism and a perverted Christianity.

From such a caste or order the whole truth is not to be expected, especially when the truth would show the order to be an imposture. The assumptions of peculiar sanctity, official pre-eminence, functional prerogatives, and special spiritual authority make such a hope unnatural and quite impossible.

The church system, with its tests of orthodoxy, its ecclesiastical handcuffs, and its worse than physical thumb-screws, puts an end to all independent thinking, and results in an enforced conformity inconsistent with intellectual progress and the discovery and full publication of the whole truth.

The pecuniary stipend upon which professional preachers are dependent has a demoralizing and degrading influence, so that the doctrinal teaching of the pulpit should not be received without hesitation and distrust. The common law excludes the testimony of interested witnesses, and, though modern statutes admit such testimony, the courts take it for what it is worth, but always with many grains of allowance. “A gift perverteth judgment,” and self-interest may sway the convictions of a man who intends and desires to be fairly honest.

The existing systems of ministerial education and support deter many superior men from entering the profession, and have placed preaching upon a commercial or mercantile basis, which has manacled and crippled the pulpit, and must sooner or later result in the consideration of the question whether the services of the clergy are worth what they cost, and whether the truth must not be sought for in some other direction. More than two hundred and fifty thousand priests and ministers (of whom about one hundred thousand are in the United States) are maintained at an annual expense of more than five hundred millions of dollars; and, as a rule, where priests are most numerous, people are poorest and public morality lowest.

A member of the Canadian Parliament (Hon. James Beatty) has recently published a book in which he opposes the whole system of a salaried clergy on scriptural and other grounds; and many other thoughtful men are beginning to inquire how it is that the Society of Friends get along so well without a “hireling ministry.”

It is a great mistake to suppose that we must look mainly to professional clergymen for instruction in divine things. It is a significant fact that the most able and important books that have been published within the last decade have been written by laymen or by persons, like Emerson, who have outgrown the narrow garments of a caste profession and have laid them off. How to get along without professional ministers has been well answered by Capt. Robert C. Adams (quoted in the writer’s book, Man—Whence and Whither? pp. 218, 219).

If ministers would give up the holy-orders idea, cast into the sea the millstone incumbrance of pecuniary dependence, engage earnestly in some legitimate work to support themselves, they would then for the first time begin to realize what soul-freedom is, and they could then preach with an intelligence and power and with a satisfaction to themselves of which they now know nothing. Let them try it for themselves and learn a lesson. Whether the clerical order is so divine an institution that we have no right to call it into question or to abolish it altogether, is a question that must be practically considered soon.

There is a deep impression widely prevailing among thoughtful and sincerely religious persons that the infidelity of the pulpit is largely responsible for the prevailing skepticism of the age. The word “infidelity” is here specially used in a strict philological sense—infidele, not faithful, unfaithfulness to a trust—but it is also used in its more general sense of disbelief in certain religious dogmas.

We impeach and arraign the clergy (admitting a few honorable exceptions) on the general charge of infidelity in the strictest and broadest sense of the word—

1st. In that they fail to qualify themselves to be the leaders of thought in the great, living questions affecting religion and morality. We have elsewhere said: “Not one minister in a thousand ‘discerns the signs of the times’ or is prepared for the crisis. Few pastors ever read anything beyond their own denominational literature. Their education is partial, one-sided, professional. They cling to mediaeval superstitions with the desperate grasp of drowning men. The great majority of the clergy are not men of broad minds and wide and deep research, and have not the ability to meet the vexed questions of to-day.”

It is an admitted policy, especially among the orthodox clergy (so called), not to read or to listen to anything that might unsettle their faith in what they have accepted as a finality; whereas no man can intelligently believe anything until he has candidly considered the reasons assigned by other men for not believing what he does. “He that is first in his own cause seemeth just; but his neighbor cometh and searcheth him.”

Professor Fisher, the champion of Yale-College orthodoxy, has recently admitted in the North American Review that at least one of the causes of the decline of clerical authority and influence is the increased intelligence of the laity. If the people cannot get what they desire from the pulpit, they will seek it from the platform and the press. Truth is no longer to be concealed in cloisters and smothered in theological seminaries, but it is to be proclaimed from housetops and in language understood in every-day life.

It was once said that “the lips of the priest give knowledge,” but it may now be truly said that modern scientists and philosophers among the laity are the principal teachers of mankind, and that publications like the North American Review and The Forum, and last, but not least, the secular daily newspapers, are doing more to instruct the people in living truths than the whole brood of ecclesiastical parrots.

2d. We charge that many professional clergymen suppress things which they do believe to be true, and not unfrequently suggest things, at least by implication, which they do know to be false.

Dr. Edward Everett Hale recently published an article in the North American Review entitled “Insincerity in the Pulpit;” and the Rev. Dr. Phillips Brooks of Boston, who recently received episcopal honors in Massachussetts, has confirmed in the Princeton Review what Dr. Hale charged in the North American Review regarding clerical disingenuousness. Dr. Brooks wrote thus:

“A large acquaintance with clerical life has led me to think that almost any company of clergymen, talking freely to each other, will express opinions which would greatly surprise, and at the same time greatly relieve, the congregations who ordinarily listen to these ministers.... How many men in the ministry to-day believe in the doctrine of verbal inspiration which our fathers held? and how many of us have frankly told the people that we do not believe it?... How many of us hold that the everlasting punishment of the wicked is a clear and certain truth of revelation? But how many of us who do not have ever said a word?”

The same principle of prevarication and deceit was practised by the early Fathers of the Christian Church, who not only concealed the truth from the masses of the people, but did not hesitate to deceive and mislead them.

Mosheim, an ecclesiastical historian of high authority, testifies that “in the fourth century it was an almost universally adopted maxim that it was an act of virtue to deceive and lie when by such means the interests of the Church might be promoted.” He further says of the fifth century, “Fraud and impudent imposture were artfully proportioned to the credulity of the vulgar.”

Milman, in his History of Christianity, says: “It was admitted and avowed that to deceive into Christianity was so valuable a service as to hallow deceit itself.” He further says in the same historical work, “That some of the Christian legends were deliberate forgeries can scarcely be questioned.” There is not a Bible manuscript or version that has not been manipulated by ecclesiastics for century after century. Many of these priests were both ignorant and vicious. From the fifth to the fifteenth century crimes not fit to be mentioned prevailed among the clergy.

Dr. Lardner says that Christians of all sorts were guilty of fraud, and quotes Cassaubon as saying, “In the earliest times of the Church it was considered a capital exploit to lend to heavenly truth the help of their own inventions.” Dr. Thomas Burnet, in a Latin treatise intended for the clergy only, said, “Too much light is hurtful to weak eyes;” and he recommended the practice of deceiving the common people for their own good. I know that this same policy is in vogue in our day. This same nefarious doctrine of the exoteric and esoteric, one thing for the priest and another for the people, is far from being dead in this nineteenth century. It has always been, and now is, the real priestly policy to keep the common people in ignorance of many things; and if all do not accept the maxim of Gregory, that “Ignorance is the mother of Devotion,” many ministers privately hold in our day that “where ignorance is bliss ’Tis folly to be wise.”

3d. The third article of impeachment, under the general charge of infidelity is, that sacerdotalists teach dogmas which they do not believe themselves. They do not all believe, ex animo, the distinctive dogmas of the orthodox creeds—that God is angry with the great body of mankind, that his wrath is a burning flame, and that there is, as to a majority of men, but a moment’s time and a point of space between them and eternal torture more terrible than imagination can conceive or language describe. It is well said that “Actions speak louder than words;” and we need only ask the question, “Do ministers who profess to believe these horrible dogmas preach as if they really believed them?” Notice the general deportment of the clergy at the summer resort, at the seaside, or on the mountain-top, and say whether they can possibly believe what for eight or nine months they have been preaching in their now closed churches. Listen to the private conversation of our evangelists at the camp-meeting or at the meetings of ecclesiastical bodies, and then conclude, if you can, that they believe what they teach.

Take, if you please, the case of one of our best-known evangelical ministers, a member of the strictest of our orthodox sects, who spends a large proportion of his time in studying the ways of insects, and who would chase a pismire across the continent to find out its habits. Can a pastor believe in his heart the dogmas of the Westminster Confession, and yet devote so much time to ants? It is impossible. He may deceive himself; he cannot deceive others.

4th. Our fourth article of impeachment under the general charge is, that the pulpit is the great promoter of skepticism called infidelity, in that it insists upon the belief of dogmas which are absurd upon their face, such as the miraculous conception of Jesus, the dogma of the Trinity, the origin and fall of man, vicarious atonement, predestination, election and reprobation, eternal torture for the majority, and many other absurdities which no rational mind can now consistently accept.

True, these dogmas may be found in the Bible; and when men ate told with weekly reiterations that the Bible is purely divine, supernatural, and infallible, and they find that it is purely human, natural, and very fallible, they cannot believe the Bible, though they find many inspiring and helpful things in it. When ministers tell thinking men that they must believe all or reject all, they accept the foolish alternative and reject all. And so it might be further shown how, in very many ways, the pulpit is the great promoter of skepticism and infidelity, and that the professed teachers of religion are its greatest enemies, its most effective clogs and successful antagonists. No wonder that the most thoughtful and intelligent men and women in every community have drifted away from the popular faith, and are anxiously inquiring, What next?

President Thomas Jefferson, in writing to Timothy Pickering, well said:

“The religion-builders have so distorted and deformed the doctrines of Jesus, so muffled them in mysticisms, fancies and falsehoods, have caricatured them into forms so monstrous and inconceivable, as to shock reasonable thinkers to revolt them against the whole, and drive them rashly to pronounce its founder an impostor.” Writing to Dr. Cooper, he said: “My opinion is that there would never have been an infidel if there had never been a priest.”

We would not abolish the office, or, if you please, the profession, of public moral teacher, but we would banish from the world the caste idea, the holy-order pretence. When simple-minded young men and grave and surpliced bishops talk about taking “holy orders,” sensible and thoughtful men know that they are talking holy nonsense. No man has a right to assume that he is more holy than other men, or that he has authority to exercise religious functions that other men have not.

Nor have we any objection that moral teachers should be paid for their services as other teachers are paid; but when educated men can afford to teach without pecuniary compensation, we think it would be well for them to do so; and when the teacher of morals adopts the example of St. Paul, “working with his own hands” and “living in his own hired house,” we think the world will be the better for it. Let us hope that the day will soon dawn when clergymen will consider themselves moral teachers only, and for ever repudiate the false pretence of special authority and priestly sanctimoniousness, and clearly understand that mediocrity and stupidity will not much longer be tolerated because of the so-called sacredness of a profession.

That the estimate here made of sacerdotalists may not seem extreme and unjustifiable, I add the testimony of one of the most honored ecclesiastics of the Established Church of England, Canon Farrar, who in a recent sermon on priestcraft said: “In all ages the exclusive predominance of priests has meant the indifference of the majority and the subjection of the few. It has meant the slavery of men who will not act, and the indolence of men who will not think, and the timidity of men who will not resist, and the indifference of men who do not care.” Alas that “holy hands” should so often be laid “upon skulls that cannot teach and will not learn”!

Let me here quote from Professor Huxley an admirable statement of the facts in the case:

“Everywhere have they (sacerdotalists) broken the spirit of wisdom and tried to stop human progress by quotations from their Bibles or books of their saints. In this nineteenth century, as at the dawn of modern physical science, the cosmogony of the semi-barbarous Hebrew is the incubus of the philosopher and the opprobrium of the orthodox. Who shall number the patient and earnest seekers after truth, from the days of Galileo until now, whose lives have been embittered and their good name blasted by the mistaken zeal of bibliolaters? Who shall count the host of weaker men whose sense of truth has been destroyed in the effort to harmonize impossibilities; whose life has been wasted in the attempt to force the generous new wine of science into the old bottles of Judaism, compelled by the outcry of the same strong party? It is true that if philosophers have suffered, their cause has been amply avenged. Extinguished theologies lie about the cradle of every science as the strangled snakes beside that of Hercules; and history records that whenever science and orthodoxy have been fairly opposed, the latter has been forced to retire from the lists, bleeding and crushed if not annihilated, scotched if not slain. But orthodoxy learns not, neither can it forget; and though at present bewildered and afraid to move, it is as willing as ever to insist that the first chapter of Genesis contains the beginning and the end of sound science, and to visit with such petty thunderbolts as its half-paralyzed hands can hurl those who refuse to degrade nature to the level of primitive Judaism.” “Religion,” he also elsewhere writes, “arising like all other knowledge out of the action and interaction of man’s mind, has taken the intellectual coverings of Fetishism, Polytheism, of Theism or Atheism, of Superstition or Rationalism; and if the religion of the present differs from that of the past, it is because the theology of the present has become more scientific than that of the past; not because it has renounced idols of wood and idols of stone, but it begins to see the necessity of breaking in pieces the idols built up of books and traditions and fine-spun ecclesiastical cobwebs, and of cherishing the noblest and most human of man’s emotions by worship, ‘for the most part of the silent sort,’ at the altar of the unknown and unknowable”... “If a man asks me what the politics of the inhabitants of the moon are, and I reply that I know not, that neither I nor any one else have any means of knowing, and that under these circumstances I decline to trouble myself about the subject at all, I do not think he has any right to call me a skeptic.” Again: “What are among the moral convictions most fondly held by barbarous and semi-barbarous people? They are the convictions that authority is the soundest basis of belief; that merit attaches to a readiness to believe; that the doubting disposition is a bad one, and skepticism a sin; and there are many excellent persons who still hold by these principles.”... “Yet we have no reason to believe that it is the improvement of our faith nor that of our morals which keeps the plague from our city; but it is the improvement of our natural knowledge. We have learned that pestilences will only take up their abode among those who have prepared unswept and ungarnished residences for them. Their cities must have narrow, un watered streets full of accumulated garbage; their houses must be ill-drained, ill-ventilated; their subjects must be ill-lighted, ill-washed, ill-fed, ill-clothed; the London of 1665 was such a city; the cities of the East, where plague has an enduring dwelling, are such cities; we in later times have learned somewhat of Nature, and partly obey her. Because of this partial improvement of our natural knowledge, and that of fractional obedience, we have no plague; but because that knowledge is very imperfect and that obedience yet incomplete, typhus is our companion and cholera our visitor.”

CHAPTER III. THE FABULOUS CLAIMS OF JUDAISM

“Not giving heed to Jewish fables.”—Tit. 1: 14.

“Neither give heed to fables.”—1 Tim. 1: 4.

“But refuse profane and old wives’ fables.”—1 Tim. 4: 7.

IT is impossible to understand modern Christian ecclesiasticism without a careful study of ancient Judaism. It is reported that Jesus himself said, “Salvation is of the Jews.” The gospel was to be preached “to the Jews first.” The common belief to-day is, that the Christian Church represents the substance of what Judaism was the promise, and that the New Testament contains the fulfilment and realization of what was foreshadowed in the Old Testament.

All well-informed theologians understand that the Christian Church is held to have had its origin in what is denominated the “call of Abraham,” and that what is known in orthodox parlance as the “Abrahamic covenant” lies at the foundation of the orthodox theory of grace and of all other systems of doctrine falsely designated as evangelical. It is a suggestive fact that while Christians hold that their religion is the very quintessence and outcome of Judaism, they most cordially hate the Jews, and the Jews in return, have a supreme contempt for Christians and stoutly deny the relationship of parent and child.

Now that the descent of the Jews from the Chaldean Abram, whom they affect to call their father, is discredited by all scholars who reject the inspirational and infallible theory of the Old Testament, it is very difficult to find out the real origin of this strange people. All modern writers on Jews and Judaism admit that outside of the Old Testament there is little or no history of the Jews down to the time of Alexander, and that there is very little reliable history even in the collection of books known as the Hebrew Scriptures. It cannot be doubted now that the Pentateuch, improperly called the five books of Moses, was mostly written after the return of the Jews from their captivity in Babylon, about 538 b. c., and what is found in these books mainly corresponds with the religion and literature of the Assyrians, and was learned during their sojourn in that country, and not, as has ignorantly been supposed, from the mythical Abram, the reputed immigrant from Ur of the Chaldees. What is recorded in the Pentateuch, not being mentioned in other Old-Testament writings, shows that such records had no existence when those books were written, and therefore could have no recognition. It will be shown hereafter that there is little or nothing in the Pentateuch that is strictly original, much less strictly historical. Indeed, the tales of the Old Testament generally were written for a religious or patriotic purpose, with little regard for time, place, or historical accuracy. Persons, real or mythical, are often used to represent different tribes, while allegory is the rule rather than the exception in what is ignorantly accepted as history. This is admitted by many eminent Christian writers.

The word “Jew” first occurs in 2 Kings 16: 6 to denote the inhabitants of Judea, but they should properly have been called “Judeans.” The very name Jew is probably mythological, derived from Jeoud, the name of the only son of Saturn, though, like Abraham, he had several other sons. It cannot be doubted that the stories of Saturn and Abraham are slightly varied versions of the same fable.

The Jews never deserved to be called a nation, at least not until in comparatively modern times. They were inclined from the first to mingle with and intermarry with other peoples, and so became mongrels at an early period.