The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pinocchio in Africa, by Cherubini This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Pinocchio in Africa Author: Cherubini Release Date: July 1, 2002 [EBook #5327] Last Updated: August 24, 2014 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PINOCCHIO IN AFRICA *** Produced by Walter Moore, James Linden and James Nugen

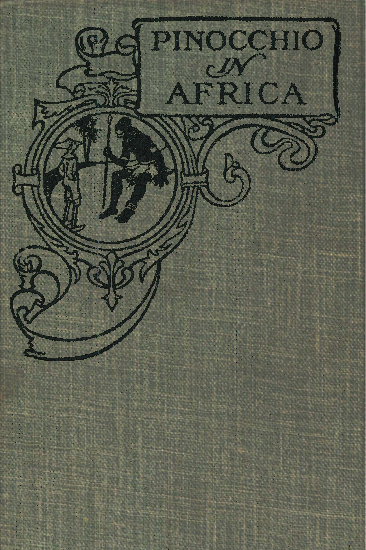

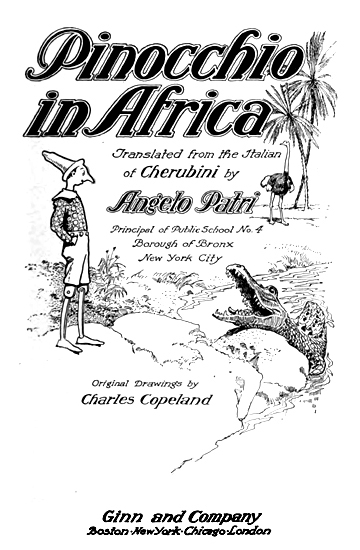

Translated

from the Italian

of Cherubini by

Angelo Patri

Principal of Public School No. 4

Borough of Bronx

New York City

Original

Drawings by

Charles Copeland

Ginn

and Company

Boston · New York · Chicago · London

Copyright,

1911, by Angelo Patri

All Rights Reserved

811.4

The

Athenaum Press

Ginn and Company Proprietors

Boston · U.S.A.

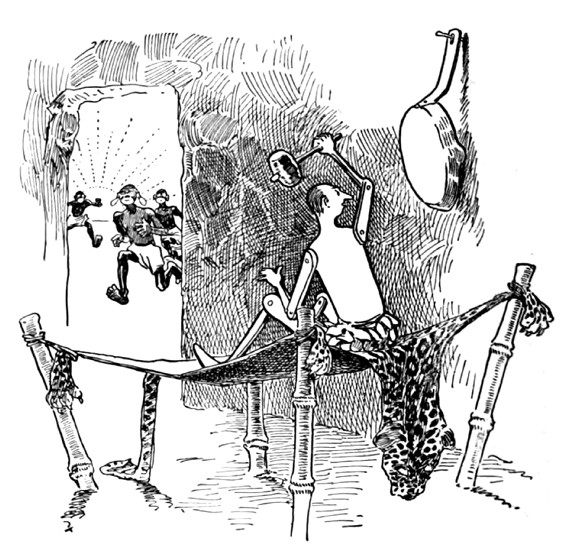

Collodi’s “Pinocchio” tells the story of a wooden marionette and of his efforts to become a real boy. Although he was kindly treated by the old woodcutter, Geppetto, who had fashioned him out of a piece of kindling wood, he was continually getting into trouble and disgrace. Even Fatina, the Fairy with the Blue Hair, could not at once change an idle, selfish marionette into a studious and reliable boy. His adventures, including his brief transformation into a donkey, give the author an opportunity to teach a needed and wholesome lesson without disagreeable moralizing.

Pinocchio immediately leaped into favor as the hero of Italian juvenile romance. The wooden marionette became a popular subject for the artist’s pencil and the storyteller’s invention. Brought across the seas, he was welcomed by American children and now appears in a new volume which sets forth his travels in Africa. The lessons underlying his fantastic experiences are clear to the youngest readers but are never allowed to become obtrusive. The amusing illustrations of the original are fully equaled in the present edition, while the whimsical nonsense which delights Italian children has been reproduced as closely as a translation permits.

One morning Pinocchio slipped out of bed before daybreak. He got up with a great desire to study, a feeling, it must be confessed, which did not often take hold of him. He dipped his wooden head into the cool, refreshing water, puffed very hard, dried himself, jumped up and down to stretch his legs, and in a few moments was seated at his small worktable.

There was his home work for the day,—twelve sums, four pages of penmanship, and the fable of “The Dog and the Rabbit” to learn by heart. He began with the fable, reciting it in a loud voice, like the hero in the play: “‘A dog was roaming about the fields, when from behind a little hill jumped a rabbit, which had been nibbling the tender grass.’

“Roaming, nibbling.—The teacher says this is beautiful language. Maybe it is; I have nothing to say about that. Well, one more.

“‘A dog was roaming about the fields—when he saw—run out—a rabbit which—which—’ I don’t know it; let’s begin again. ‘A dog was running about eating, eating—’ But eating what? Surely he did not eat grass!

“This fable is very hard; I cannot learn it. Well, I never did have much luck with dogs and rabbits! Let me try the sums. Eight and seven, seventeen; and three, nineteen; and six, twenty-three, put down two and carry three. Nine and three, eleven; and four, fourteen; put down the whole number—one, four; total, four hundred thirteen.

“Ah! good! very good! I do not wish to boast, but I have always had a great liking for arithmetic. Now to prove the answer: eight and seven, sixteen; and three, twenty-one; and six, twenty-four; put down four—why! it’s wrong! Eight and seven, fourteen; and three, nineteen; and six—wrong again!

“I know what the trouble is; the wind is not in the right quarter to-day for sums. Perhaps it would be better to take a walk in the open.”

No sooner said than done. Pinocchio went out into the street and filled his lungs with the fresh morning air.

“Ah! here, at least, one can breathe. It is a pity that I am beginning to feel hungry! Strange how things go wrong sometimes! Take the lessons—” he went on.

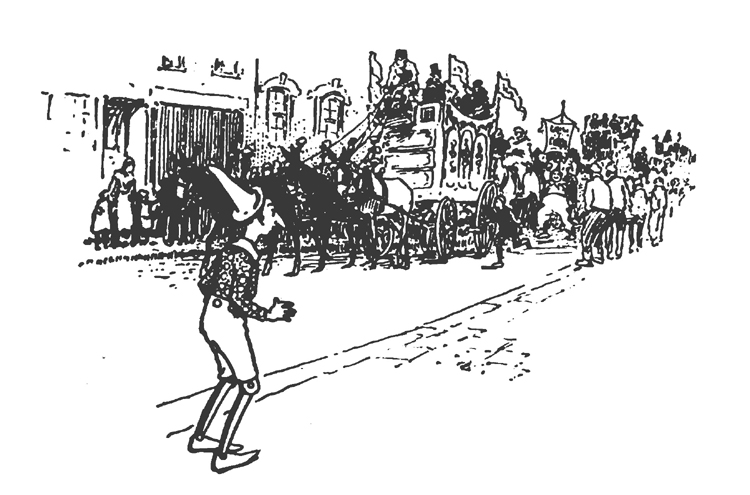

Listen! A noise of creaking wheels, of bells ringing, the voices of people, the cries of animals! Pinocchio stopped short. What could it all mean?

Down the street came a huge wagon drawn by three big mules. Behind it was a long train of men and women dressed in the strangest fashion. Some were on foot, some on horseback, some sat or lay on other wagons larger and heavier than the first. Two Moors, their scarlet turbans blazing in the sun, brought up the rear. With spears at rest and with shields held before them, they rode along, mounted on two snow-white horses.

Pinocchio stood with his mouth open. Only after the two Moors had passed did he discover the fact that he had legs, and that these were following on behind the procession. And he walked, walked, walked, until the carriages and all the people stopped in the big town square. A man with a deep voice began to give orders. In a short time there arose an immense tent, which hid from Pinocchio and the many others who had gathered in the square all those wonderful wagons, horses, mules, and strange people.

It may seem odd, but it is a fact that the school bell began to ring and Pinocchio never heard it!

That day the school bell rang longer and louder perhaps than it was wont to ring on other days. What of that? From the tent came the loud clanging of hammers, the sounds of instruments, the neighing of horses, the roaring of lions and tigers and panthers, the howling of wolves, the bleating of camels, the screeching of monkeys! Wonderful noises! Who cared for the school bell? Pinocchio? No, not he.

Suddenly there was a loud command. All was still.

The two Moors raised the tent folds with their spears. Out came a crowd of men dressed in all sorts of fine clothes, and women in coats of mail and beautiful cloaks of silk, with splendid diadems on their heads. They were all mounted upon horses covered with rich trappings of red and white.

Out they marched, and behind them came a golden carriage drawn by four white ponies. In it was the big man with the deep voice. There he sat in the beautiful carriage with his dazzling high hat and his tall white collar. He wore a black suit with a pair of high boots. As he rode on he waved his white gloves and bowed right and left. The band with its trumpets and drums and cymbals struck up a stirring march, and a parade such as the townsfolk had never seen before passed out among the crowds that now filled the square.

The marionette could not believe his eyes. He rubbed them to see if he was really awake. He forgot all about his hunger. What did he care for that? The wonders of the whole world were before him.

The parade soon reentered the tent. The two Moors, mounted upon their snow-white horses, again stood at the entrance. Then the director, the man with the loud voice, came out, hat in hand, and began to address the people.

“Ladies and gentlemen! kind and gentle people! citizens of a great town! officers and soldiers! I wish you all peace, health, and plenty.

“Ladies and gentlemen, first of all, let me make a brief explanation. I am not here for gain. Far be it from me to think of such a thing as money. I travel the world over with my menagerie, which is made up of rare animals brought by me from the heart of Africa. I perform only in large cities. But to-day one of the monkeys in the troupe is fallen seriously ill. It is therefore necessary to make a short stop in order that we may consult with some well-known doctor in this town.

“Profit, therefore, by this chance, ladies and gentlemen, to see wonders which you have never seen before, and which you may never see again. I labor to spread learning, and I work to teach the masses, for I love the common people. Come forward, and I shall be glad to open my menagerie to you. Forward, forward, ladies and gentlemen! two small francs will admit you. Children one franc, yes, only one franc.”

Pinocchio, who stood in the front row, and who was ready to take advantage of the kind invitation, felt a sudden shock on hearing these last words. He looked at the director in a dazed fashion, as if to say to him, “What are you talking about? Did you not say that you traveled around the world for—”

Then, as he saw one of the spectators put down a two-franc piece and walk inside, he hung his head and suffered in silence.

Having passed two or three minutes in painful thinking, the forlorn marionette put his hands into his pockets, hoping to find in them a forgotten coin. He found nothing but a few buttons.

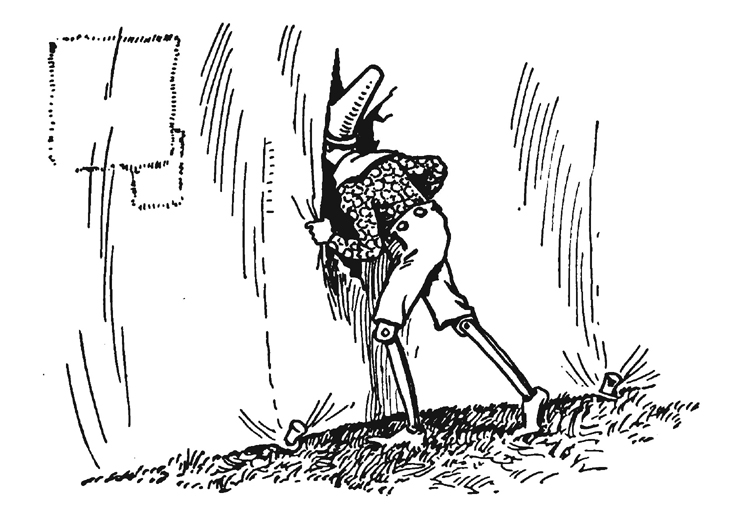

He racked his brains to think of some plan whereby he could get the money that was needed. He glanced at his clothes, which he would cheerfully have sold could he have found a buyer. Not knowing what else to do, he walked around the tent like a wolf prowling about the sheepfold.

Around and around he went till he found himself near an old wall which hid him from view. He came nearer the tent and to his joy discovered a tiny hole in the canvas. Here was his chance! He thrust in his thin wooden finger, but seized with a sudden fear lest some hungry lion should see it and bite it off, he hastily tried to pull it out again. In doing this, somehow “r-r-rip” went the canvas, and there was a tear a yard wide. Pinocchio shook with fear. But fear or no fear, there was the hole and beyond—were the wonders of Africa!

First an arm, then his head, and then his whole body went into the cage of wild animals! He could not see them, but he heard them, and he was filled with awe. The beasts had seen him. He felt himself grasped at once by the shoulders and by the end of his nose. Two or three voices shouted in his ears, “Who goes there?”

“For pity’s sake, Mr. Elephant!” said poor Pinocchio.

“There are no elephants here.”

“Pardon, Sir Lion.”

“There are no lions here.”

“Excuse me, Mr. Tiger.”

“There are no tigers.”

“Mr. Monkey?”

“No Monkeys.

“Men?”

“There are neither men nor women here; there are only Africans from Africa, who imitate wild beasts for two francs and a half a day.”

“But the elephants, where are they?”

“In Africa.”

“And the lions?”

“In Africa.”

“And the tigers and the monkeys?”

“In Africa. And you, where do you come from? What are you doing in the cage of the wild beasts? Didn’t you see what is written over the door? NO ONE ALLOWED TO ENTER.”

“I cannot read in the dark,” replied Pinocchio, trembling from head to foot; “I am no cat.”

At these words everybody began to laugh. Pinocchio felt a little encouraged and murmured to himself, “They seem to be kind people, these wild beasts.”

He wanted to say something pleasant to them, but just then the director of the company began to shout at the top of his voice.

“Come forward, come forward, ladies and gentlemen! The cost is small and the pleasure is great. The show will last an hour, only one hour. Come forward! See the battle between the terrible lion Zumbo and his wife, the ferocious lioness Zumba. Behold the tiger that wrestles with the polar bear, and the elephant that lifts the whole weight of the tent with his powerful trunk. See the animals feed. Ladies and gentlemen, come forward! Only two francs!”

At these words the men in the cages of the wild animals put horns, sea shells, and whistles to their mouths, and the next moment there came wild roarings and howls and shrieks. It was enough to make one shudder with fear.

Again the director raised his voice: “Come forward, come forward, ladies and gentlemen! two francs; children only one franc.”

The music started: Boom! Boom! Boom! Par-ap’-ap’-pa! Boom! Boom! Boom! Par-ap’ ap’ ap’ pa! parap’ ap’ ap’ pa!

One surprise seemed to follow another. Pinocchio longed to enjoy the sights, but how was he to get out of the cage? At length, taking his courage in both hands, he said politely, “Excuse me, gentlemen, but if you have no commands to give me—”

“Not a command!” roughly answered the bearded man who played the lion. “If you do not go away quickly, I will have you eaten up by that large ape behind you.”

“But I should be hard to digest,” said the marionette.

“Boy, be careful how you talk,” exclaimed the same voice.

“I said that your ape would have indigestion if he ate me,” replied Pinocchio. “Do you think that I am joking? No, I am in earnest. He really would. I came in here by chance while returning from a walk, and if you will permit me, I will go home to my father who is waiting for me. As you have no orders to give me, many thanks, good-by, and good luck to you.”

“Listen, boy,” said the large man who took the part of the elephant; “I am very thirsty, and I will give you a fine new penny if you will fill this bucket at the fountain and bring it to me.”

“What!” replied Pinocchio, greatly offended; “I am no servant! However this time, merely to please you, I will go.” And crawling through the hole by which he had entered, he went out to the fountain and returned in a very short time with the bucket full of water.

“Good boy, good marionette!” said the men as they passed the bucket from one to another.

Pinocchio was happy. Never had he felt so happy as at that moment. “What good people!” he said to himself. “I would gladly stay with them.” In the meantime the bucket was emptied, and there were still some who had not had a drink. “I will go and refill it,” said the marionette promptly. And without waiting to be asked, he took the bucket and flew to the fountain.

When he returned they flattered him so cleverly with praise and thanks that a strong friendship sprang up between Pinocchio and the wild beasts.

Being a woodenhead he forgot about his father and did not go away as he had intended to do. In fact, he was curious to know something of the history of these people, who were forced to play at being wild animals.

After a moment’s silence he turned to the one who had asked him to go for the water and said, “You are from Africa?”

“Yes, I am an African, and all my companions are African.”

“How interesting! but pardon me, is Africa a beautiful country?”

“I should say so! A country, my dear boy, full of plenty, where everything is given away free! A country in which at any moment the strangest things may happen. A servant may become a master; a plain citizen may become a king. There are trees, taller than church steeples, with branches touching the ground, so that one may gather sweet fruit without the least trouble. My boy, Africa is a country full of enchanted forests, where the game allows itself to be killed, quartered, and hung; where riches—”

No one knows how far this description would have gone, if at that moment the voice of the director had not been heard. The music had stopped, and the director was talking to the people, who did not seem very willing to part with their money.

Pinocchio had already resolved to go to Africa to eat of the fruit and to gather riches. He was eager to learn more, and impatient of interruption.

“And the director is an African also?”

“Certainly he is an African.”

“And is he very rich?”

“Is he rich? Take my word for it that if he would, he could buy up this whole country.”

Pinocchio was struck dumb. Still he wanted to make the men believe that what he had heard was not altogether new to him. “Oh, I know that Africa is a very beautiful country, and I have often planned to go there,—and—if I were sure that it would not be too much trouble I would willingly go with you.”

“With us? We are not going to Africa.”

“What a pity! I thought I could make the journey in your company.”

“Are you in earnest?” asked the bearded man. “Do you believe that there is any Africa outside this tent?”

“Tent or no tent, I have decided to go to Africa, and I shall go,” boldly replied the marionette.

“I like that youngster,” said the man who played the part of a crocodile. “That boy will make his fortune someday.”

“Of course I shall!” continued Pinocchio. “I ought to have fifty thousand francs, because I must get a new jacket for my father, who sold his old one to buy me a spelling book. If there is so much gold and silver in Africa, I will fill up a thousand vessels. Is it true that there is a great deal of gold and silver?”

“Did we not tell you so?” replied another voice. “Why, if I had not lost all that I had put in my pockets before leaving Africa, by this time I should have become a prince. And now were it not for the fact that I have promised to stay with these people, to be a panther at two francs and a half a day, I would gladly go along with you.”

“Thank you; thank you for your good intentions,” answered the marionette. “In case you decide to go with me, I start to-morrow morning at dawn.”

“On what steamship?”

“What did you say?” asked Pinocchio.

“On what steamship do you sail?”

“Sail! I am going on foot.”

At these words everybody laughed.

“There is little to laugh at, my dear people. If you knew how many miles I have traveled on these legs by day and by night, over land and sea, you would not laugh. What! do you think Fairyland, the country of the Blockheads, and the Island of the Bees are reached in a single stride? I go to Africa, and I go on foot.”

“But it is necessary to cross the Mediterranean Sea.”

“It will be crossed.”

“On foot?”

“Either on foot or on horseback, it matters little. But pardon me, after crossing the Mediterranean Sea, do you reach Africa?”

“Certainly, unless you wish to go by way of the Red Sea.”

“The Red Sea? No, truly!”

“Perhaps the route over the Red Sea would be better.”

“I do not wish to go near the Red Sea.”

“And why?” asked the wolf man, who up to this time had not opened his mouth.

“Why? Why? Because I do not wish to get my clothes dyed; do you understand?”

More laughter greeted these words. Pinocchio’s wooden cheeks got very red, and he sputtered: “This is no way to treat a gentleman. I shall do as I please, and I do not please to enter the Red Sea. That is enough. Now I shall leave you,” and he started off.

“Farewell, farewell, marionette!”

“Farewell, you impolite beasts!” Pinocchio wanted to call out, but he did not.

“Come back!” cried the bearded man; “here is the bucket; please fill it once more, for I am still thirsty.”

Pinocchio went away very angry, vowing that he would avenge himself on all who had laughed at him.

“To begin with,” said he, “I intend to make them all die of thirst. If they wait to drink of the water that I bring, they will certainly die.” With these thoughts in his mind the marionette started homeward, carrying the bucket on his head.

“The bucket will repay me for all the work I have had put upon me. How unlucky we children are! Wherever we go, there is always something for us to do. To-day I thought I would simply enjoy myself; instead, I have had to carry water for a company of strangers. How absurd! two trips, one after the other, to give drink to people I do not know! And how they drink! they seem to be sponges. For my part they can be thirsty as long as they like. I feel now as if I would never again move a finger for them. I am not going to be laughed at.”

As he finished these remarks Pinocchio arrived at the fountain. It was delightful to see the clear water rushing out, but he could not help thinking of those poor creatures who were waiting for him. He had to stop.

“Shall I or shall I not?” he asked himself. “After all, they are good people, who are forced to imitate wild animals; and besides, they have treated me with some kindness. I may as well carry some water to them; a trip more or less makes no difference to me.”

He approached the fountain, filled the bucket, and ran down the road.

“Hello within there!” he said in a low voice. “Here is the bucket of water; come and take it, for I am not going in.”

“Good marionette,” said the beasts, “thank you!”

“Don’t mention it,” replied Pinocchio, very happy.

“Why will you not come in?”

“It is impossible, thank you. I must go to school.”

“Then you are not going to Africa?”

“Who told you that! I am returning to school to bid farewell to my teacher, and to ask him to excuse me for a few days. Then I wish to see my father and ask his permission to go, so that he will not be anxious while I am away.”

“Excellent marionette, you will become famous.”

“What agreeable people!” thought Pinocchio. “I am sorry to leave them.”

“So you really will not come in?”

“No, I have said so before. I must go to school first, and then—”

“But it seems to me rather late for school,” said the crocodile man.

“That is true; it is too late for school,” replied Pinocchio.

“Well, then, stay a little longer with us, and later you can go home to your father.”

Pinocchio thrust his head through the hole and leaped into the tent. The naughty marionette had not the least desire to go to school, and was only too glad of an excuse to watch these strange people.

The show had begun. The director was explaining to the people the wonders of his menagerie.

“Ladies and gentlemen, observe the beauty and the wildness of all these animals, which I have brought from Central Africa. Here they are, inclosed in these many cages, but hidden from your view. Why are they hidden? Because, ladies and gentlemen, you would be frightened at the sight of them, and your peace and health greatly concern me. The first animal which I have the pleasure to present to you is the elephant. Observe, ladies and gentlemen, that small affair which hangs under his nose. With that he builds houses, tills the soil, writes letters, carries trunks, and picks flowers. You can see that the animal was painted from life and placed in this beautiful frame.”

The people began to look at one another.

“Now, ladies and gentlemen, let us go on to the next one.”

A roar of laughter and jeers arose on all sides. The director saw the unfortunate state of things and began to shout: “Have respect, ladies, for the poor sick monkey I told you of. At this moment she is pressing to her breast for the last time her friendless child.”

But not even this was sufficient to calm the crowd, which presently became an infuriated mob. Men and women rushed about the tent, making fierce gestures and heaping abuse upon the director. What an uproar!

In the cage where Pinocchio was, there was no confusion, and the conversation between the marionette and the wild beasts went on without stopping.

“When do you leave for Africa?” Pinocchio was asked.

“Have I not told you? To-morrow morning at daybreak, even if it rains.”

“Excellent! But you must carry with you several things which you may need.”

“And those are—?”

“First of all you will need plenty of money.”

“That is not lacking,” said Pinocchio in his usual airy way.

“Good! Then you should get a rifle.”

“What for?”

“To defend yourself against the wild animals.”

“Come, come! You don’t want me to believe that! I have seen what the wild animals of Africa are!”

“Be careful, marionette. Take a good rifle with you, for one never knows what will happen in Africa.”

“But I do not know how to load one.”

“Well, then, stay at home. It is folly for you to begin such an undertaking without arms and without knowing how to use them.”

“It is you who are foolish. Do not make me angry. When I have decided upon a thing no one can stop me from carrying it out.”

“Take care, marionette; you may be sorry.”

“Nevertheless I shall go.”

“You may find things very unpleasant.”

“It is for that very reason that I am going.”

“You may never return.”

“The good Fairy will protect me.”

“Who is the Fairy?”

“How many things you want to know! If you are in need of nothing else, I will bid you all good-by!”

“Farewell, marionette.”

“Till we meet again.”

“Good-by, blockhead.”

“Don’t be rude! said Pinocchio, greatly vexed, and out he went.

When Pinocchio arrived at his home he found his father already in bed. Old Geppetto did not earn enough to provide a supper for two. He used to say that he was not hungry, and go to bed. But there was always plenty for Pinocchio. An onion, some beans moistened in water, and a piece of bread which had been left over from the morning, were never missing.

That night Pinocchio found a better meal than usual.

His good father, not having seen his son at the regular dinner hour, knew that the boy would be very hungry. There would have to be something out of the ordinary. He therefore added to the fare some dried fish and a delicious morsel of orange peel. “He will even have fruit,” the good man had said to himself, smiling at the joy his dear Pinocchio would feel on seeing himself treated like a man of the world.

The marionette ate his supper with relish, and having finished his meal, went over to his sleeping father and kissed him as a reward for the fish and the orange peel. Pinocchio, to say the least, had a good heart, and would have done anything for his father except study and work.

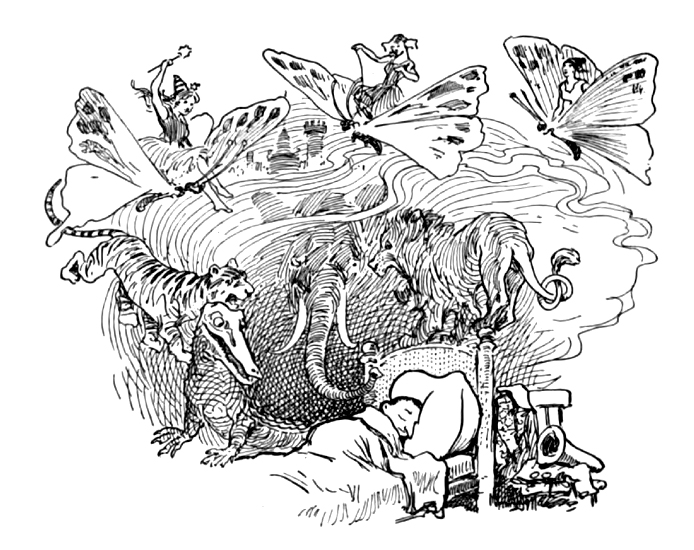

That night he slept little. Lions, elephants, tigers, panthers, beautiful women dressed in silk and mounted on butterflies as large as eagles, men, in large boots, armed with knives and guns, palaces of silver and gold! All these and a great many more strange sights floated before his dreaming eyes, while he could hear animals roaring, howling, and whistling to the sound of trumpets and drums.

At length the night ended and Pinocchio arose. First of all he went to bid farewell to his friends in the circus, but they were no longer to be found. During the night the director had quietly stolen away with his company.

“A pleasant journey to you!” said Pinocchio, and he began to search the ground for a forgotten piece of gold, or some precious stone which might have fallen from a lady’s diadem; but he found nothing.

“What shall I do now? Shall I go to Africa or to school? It might be better to go to school, for the teacher says that I am a little behind in reading, writing, composition, history, geography, and arithmetic. In other subjects I am not so dull. Yes, yes; it will certainly do me more good to go to school. Then I shall be a dunce no longer.”

Having made this sensible decision, the marionette started for home with the idea of studying his lessons and of going to school.

Soon he met a man in a paper hat and a white apron. He was pushing a cart filled with a kind of fruit that Pinocchio had never seen before.

“Dates! dates! fresh dates! sweet dates! real African dates!” came the cry.

“Even he speaks of Africa!” thought Pinocchio. “Africa seems to follow me. But what has Africa to do with dates, and what are these dates? I have never heard of them.” The man stopped; Pinocchio stopped also. A lady bought some of the dates, and it happened that one of them fell on the ground. The marionette picked it up and handed it to her.

“Thank you,” she said with a smile. “Keep it yourself; you have earned it.”

The man with the cart went on, “Dates! dates! fresh dates! sweet dates! real African dates!”

Pinocchio looked after him for a time and then put the date into his mouth. Great Caesar! How delicious! Never before had he tasted anything so sweet. The orange peel was nothing compared with this! What the circus people had told him, then, was really true!

“To Africa I go,” he said, “even if I break a leg. What do I care about the Red Sea, the Yellow Sea, the Green, or any other sea? I will go!”

And the rascal, forgetting his home and his father, who at that very moment was waiting to give him his breakfast, set out toward the sea.

As he neared the water he heard a voice call, “Pinocchio! Pinocchio!”

The marionette stopped and looked around, but seeing no one, he went on.

“Pinocchio! Pinocchio! Be careful! You know not what you do!”

“Farewell and many thanks,” answered the stubborn marionette, and forthwith stepped into the sea.

“The water is like ice this morning. No wonder it makes me feel cold; but I know how to get rid of a chill. A good swim, and I am as warm as ever.” Out shot his arms and he plunged into the water. The journey to Africa had begun.

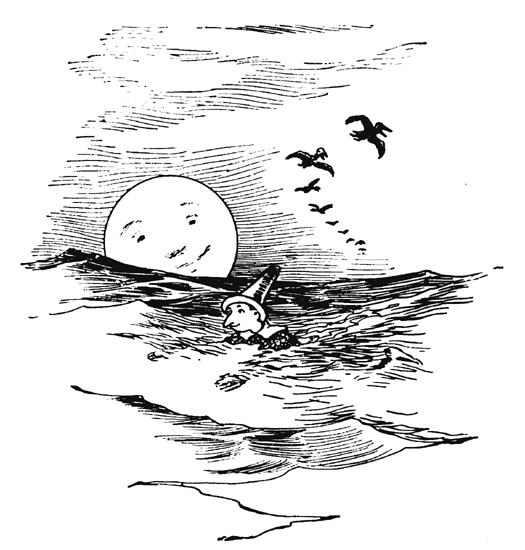

At noon he still swam on. It grew dark and on he swam. Later the moon arose and grinned at him. He kept on swimming, without a sign of fatigue, of hunger, or of sleepiness. A marionette can do things that would tire a real boy, and to Pinocchio swimming was no task at all.

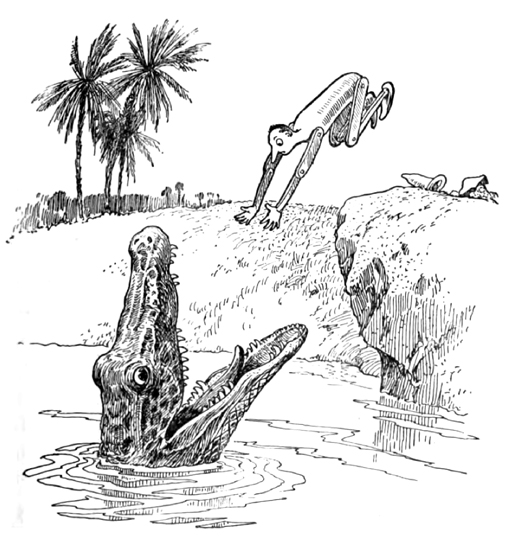

The moon grinned again and disappeared behind a cloud. The night grew dark. Pinocchio continued to swim through the black waters. He could see nothing ahead. He swam, swam, swam into the dark. Suddenly he felt something scrape his body, and he gave a start.

“Who goes there?” he cried. No one answered. “Perhaps it is my old friend the shark, who has recognized me,” thought he; and he rapidly swam on to get away from the spot which reminded him of that terrible monster.

He had not gone more than fifty yards when his head ran against something rough and hard. “Oh!” cried the marionette, and he raised his hand to the injured part.

Then, as he noticed a large rock standing out of the water, he cried joyously; “I have arrived! I am in Africa!”

He got up on his feet and began to feel of himself all over,—his ribs, his stomach, his legs. Everything was in order.

“Nothing broken!” he said. “The rocks on the way have been very kind. However, I hope that day will break soon, for I have no matches, and it seems to me that I am very hungry.”

Then he began to move on carefully. First he put down one foot and then the other, and thus crept along till he found a comfortable spot. “I seem to be very tired and sleepy also,” he said.

With that, he lay down and went off in to a deep slumber.

When he awoke it was daylight. The sun shone red and hot. There was nothing to be seen but rocks and water.

“Is this Africa?” said the marionette, greatly troubled. “Even at dawn it seems to be very warm. When the sun gets a little higher I am likely to be baked.” And he wiped the sweat from his brow on his coat sleeve. Presently clouds began to rise out of the water. They grew darker and darker, and the day, instead of being bright, gradually became gloomy and overcast.

The sun disappeared.

“This is funny!” said Pinocchio. “What jokes the sun plays in these parts! It shines for a while and then disappears.”

Poor marionette! It did not occur to him at first that he had slept the whole day, and that instead of the rising he saw the setting of the sun.

“And now I must pass another night here alone on these bare rocks!” he thought.

The unhappy marionette began to tremble. He tried to walk, but the night was so dark that it was impossible to see where to go. The tears rolled down his wooden cheeks. He thought of his disobedience and of his stubbornness. He remembered the warnings his father had given him, the advice of his teacher, and the kindly words of the good Fairy. He remembered the promises he had made to be good, obedient, and studious. How happy he had been! He recalled the day when his father’s face beamed with pleasure at his progress. He saw the happy smile with which his protecting Fairy greeted him. His tears fell fast, and sobs rent his heart.

“If I should die, here in this gloomy place! If I should die of weariness, of hunger, of fear! To die a marionette without having had the happiness of becoming a real boy!”

He wept bitterly, and yet his troubles had scarcely begun. Even while his tears were flowing down his cheeks and into the dark water, he heard prolonged howls. At the same time he saw lights moving to and fro, as if driven by the wind.

“What in the world is this? Who is carrying those lanterns?” asked Pinocchio, continuing to sob.

As if in answer to his questions, two lights came down the rocky coast and drew nearer to him.

Along with the lights came the howls, which sounded like those he had heard at the circus, only more natural and terrible.

“I hope this will end well,” the marionette said to himself, “but I have some doubt about it.”

He threw himself on the ground and tried to hide between the rocks. A minute later and he felt a warm breath on his face. There stood the shadowy form of a hyena, its open mouth ready to devour the marionette at one gulp.

“I am done for!” and Pinocchio shut his eyes and gave a last thought to his dear father and his beloved Fatina. But the beast, after sniffing at him once or twice from head to foot, burst into a loud, howling laugh and walked away. He had no appetite for wooden boys.

“May you never return!” said Pinocchio, raising his head a little and straining his eyes to pierce the darkness about him. “Oh, if there were only a tree, or a wall, or anything to climb up on!”

The marionette was right in wishing for something to keep him far above the ground. During the whole night these visitors were coming and going. They came around him howling, sniffing, laughing, mocking. As each one ran off, Pinocchio would say, “May you never return!” He lay there shivering in the agony of his terror. If the night had continued much longer, the poor fellow would have died of fright. But the dawn came at last. All these strange night visitors disappeared. Pinocchio tried to get up. He could not move. His legs and arms were stiff. A terrible weakness had seized him, and the world swam around him. Hunger overpowered him. The poor marionette felt that he should surely die. “How terrible,” he thought, “to die of hunger! What would I not eat! Dry beans and cherry stems would be delicious.” He looked eagerly around, but there was not even a cricket or a snail in sight. There was nothing, nothing but rocks.

Suddenly, however, a faint cry came from his parched throat. Was it possible? A few feet from him there was something between the rocks which looked like food. The marionette did not know what it was. He dragged himself along on hands and knees, and commenced to eat it. His nose wished to have nothing to do with it, and would even have drawn back, but the marionette said; “It is necessary to accustom yourself to all things, my friends. One must have patience. Don’t be afraid; if I find any roses, I promise to gather them for you.”

The nose became quiet, the mouth ate, the hunger was satisfied, and when the meal was finished Pinocchio jumped to his feet and shouted joyously; “I have had my first meal in Africa. Now I must begin my search for wealth.” He forgot the night, his father, and Fatina. His only thought was to get farther away from home.

What an easy thing life is to a wooden marionette!

“First of all,” he said, “I must go to the nearest castle I can find. The master will not refuse me shelter and food. Some soup, a leg of roast chicken, and a glass of milk will put me in fine spirits.”

The journey across the rocks was full of difficulties, but the marionette overcame them readily, leaping from rock to rock like a goat. He walked, walked, walked! The rocks seemed to have no ending, and the castle, which he imagined he saw in the distance, appeared to be always farther and farther away. As the marionette drew nearer, the towers began to disappear and the walls to crumble. He walked on broken-hearted. Finally he sat down in despair and put his head in his hands. “Farewell, castle! good-by, roast chicken and soup!” He was about to weep again when he saw in the distance a village of great beauty lying at the foot of a gentle slope.

At the sight he gave a cry of joy and without a moment’s delay set out in that direction. He leaped over the rocks and bushes, putting to flight several flocks of birds in his haste. Of course only a marionette could go as fast as he did. “How beautiful Africa is!” said he. “If I had known this I would have come here long ago.”

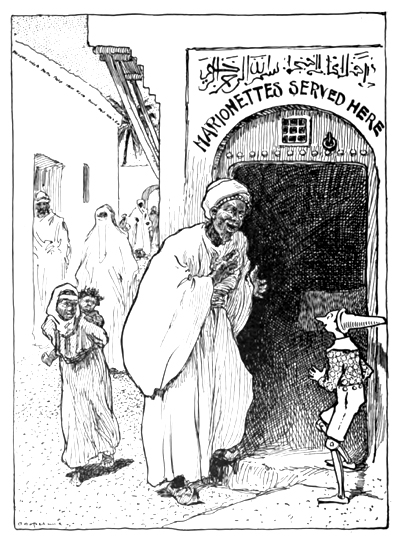

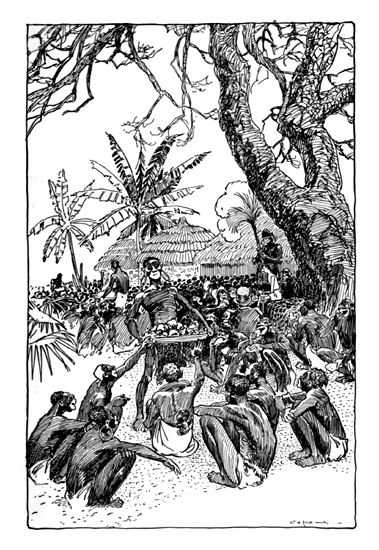

In a short time he reached the main square of the town. Men, women, and children were lounging about, gossiping, buying, and selling. When they saw the marionette they gathered around him, and many began to shout: “It is Pinocchio! Look, here is Pinocchio! Pinocchio! Pinocchio!”

“Well, this is strange!” said the marionette to himself. “I am known even in Africa. Surely I am a great person.”

Like most great men, Pinocchio was annoyed at his noisy reception. In some anger he made his way through the crowd, pushing people right and left with his elbows. He ran down a side street and finally stopped before a restaurant, over which was the sign printed in huge letters:

MARIONETTES SERVED HERE.

“This is what I have been looking for,” said Pinocchio, and he went in.

Pinocchio found himself facing a man of about fifty years of age. He was stout and good-natured, and like all good hosts, asked what the gentleman would have to eat. Pinocchio, hearing himself called “gentleman,” swelled with pride, and very gravely gave his order. He was served promptly, and devoured everything before him in a way known only to hungry marionettes.

In the meantime the innkeeper eyed his customer from head to foot. He addressed Pinocchio in a very respectful manner, but the marionette gave only short answers. Persons of rank ate here, and to appear like one of them he could not allow himself to waste words on common folk.

Having finished his meal, the marionette asked for something to drink.

“What is this drink called?” he asked, as he put down the glass and thrust his thumb into his vest pocket after the manner of a gentleman.

“Nectar, your excellency.”

Upon hearing himself called “excellency” Pinocchio fairly lost his head. He felt a strange lightness in his feet; indeed, he found it hard work to resist the temptation to get up and dance. “I knew that in Africa I should make my fortune,” he thought, and called for a box of cigarettes.

Having smoked one of these, the brave Pinocchio arose to go out, when the host handed him a sheet of paper on which was written a row of figures.

“What is this?” asked the marionette.

“The bill, your excellency; the amount of your debt for the dinner.”

Pinocchio stroked his wooden chin and looked at the innkeeper in surprise.

“Is there anything astonishing about that, your excellence? Is it not usual in your country to pay for what you eat?”

“It is amazing! I do not know what you mean! What strange custom is this that you speak of?”

“In these parts, your excellency,” remarked the innkeeper, “when one eats, one must pay. However, if your lordship has no money, and intends to live at the expense of others, I have a very good remedy. One minute!”

So saying, the man stepped out of the door, uttered a curious sound, and then returned.

Pinocchio lost his courage. He broke down and began to weep. He begged the man to have patience. The first piece of gold he found would pay for the meal. The innkeeper smiled as he said, “I am sorry, but the thing is done.”

“What is done?” asked the marionette.

“I have sent for the police.”

“The police!” cried the marionette, shaking with fear. “The police! Even in Africa there are policemen? Please, sir, send them back! I do not want to go to prison.”

All this was useless talk. Two black policemen were already there. Straight toward the marionette they went and asked his name.

“Pinocchio,” he answered in a faint voice.

“What is your business?”

“I am a marionette.”

“Why have you come to Africa?”

“I will tell you,” replied Pinocchio, “You gentlemen must know that my poor father sold his coat to buy me a spelling book, and as I have heard that there is plenty of gold and silver in Africa, I have come here.”

“What kind of talk is this?” asked the elder of the two policemen. “No nonsense! Show us your papers.”

“What papers! I left all I had at school.”

The policemen cut short the marionette’s words by taking out their handcuffs and preparing to lead him away to prison. But the innkeeper was a good-hearted man, and he was sorry for the poor blockhead. He begged them to leave Pinocchio in his charge.

“So long as you are satisfied, we are satisfied,” said the policemen. “If you wish to give away your food, that is your own affair;” and they went off without saying another word.

Pinocchio blushed with shame.

“Then you are the marionette Pinocchio?”

Upon hearing himself addressed in this familiar way, Pinocchio felt a little annoyed, but recalling the unsettled account, he thought it best to answer politely that he was Pinocchio.

“I am pleased,” continued the man; “I am very much pleased, because I knew your father.”

“You knew my father?” exclaimed the marionette.

“Certainly I knew him! I was a servant in his house before you were born.”

“In my house as a servant? When has father Geppetto had servants?” asked the marionette, his eyes wide with surprise.

“But who said Geppetto? Geppetto is not your father’s name.”

“Oh, indeed! Well, then, what is his name?”

“Your father’s name is not Geppetto, but Collodi. A wonderful man, my boy.”

Pinocchio understood less and less. It was strange, he thought, to have come to Africa to learn the story of his family. He listened with astonishment to all that the innkeeper said.

“Remember, however, that even if you are not really the son of the good Geppetto, it does not follow that you should forget the care he has given you. What gratitude have you shown him? You ran away from home without even telling him. Who knows how unhappy the poor old man may be! You never will understand what suffering you cause your parents. Such blockheads as you are not fit to have parents. They work from morning till night so that you may want for nothing, and may grow up to be good and wise men, useful to yourselves, to your family, and to your country. What do you do? Nothing! You are worthless!”

Pinocchio listened very thoughtfully. He had never expected that in Africa he was to hear so many disagreeable truths, and he was on the verge of weeping.

“For your father’s sake you have been let off easily. From now on you may regard this as your home. I am not very rich, and I need a boy to help me. You will do. You may as well begin to work at once.” And he handed the marionette a large broom.

Pinocchio was vexed at this, but the thought of the black policemen and the unsettled bill cooled his anger, and he swept as well as he knew how. “From a gentleman to a sweeper! What fine progress I have made!” he thought, as the tears rolled down his cheeks.

“If my father were to see me now, or my good Fairy, or my companions at school! What a fine picture I should make!” And he continued to sweep and dust.

The time passed quickly. At the dinner hour Pinocchio had a great appetite and ate with much enjoyment. The master praised him highly for the tidy appearance of the store and urged him to keep up his good work.

“At the end of twenty years,” he said, “You will have put aside enough to return home, and a little extra money to spend on poor old Geppetto. Now that you have eaten, take this leather bag and fill it with water, which you are to sell about the city. When you return we shall know how much you have made.”

The bag was soon strapped on his shoulders and the marionette was shown the door. “Remember,” said his master, “a cent a glass!”

Pinocchio set out down the narrow street. He walked on, little caring where he went. His wooden brains were far away. He was grieved. Had the master known just how the marionette felt he would have run after him and at least regained his leather bag.

Pinocchio walked on. He was soon among a hurrying crowd of people. “Can this be Egypt in Africa? I have read about it often.”

A man, wrapped in a white cloak, touched him on the shoulder. Pinocchio did not understand, and started to go on about his business, but the man took him roughly by the nose. Pinocchio shrieked. The crowd stopped. At last, he discovered that the man wanted water. Pinocchio placed the bag on the ground. Then he poured the water into a glass. The man drank, paid, and went his way.

“What a thirst for water Africans have!” thought the marionette, as he remembered his companions of the circus. “I like ices better, and I am going to try to get one with this penny.” At once he started off, leaving the leather bag behind.

A crowd of boys had by this time gathered in the street. They began, after the manner of boys in nearly every part of the world, to annoy one who was clearly a stranger. They did not know Pinocchio, however, nor the force of his feet and elbows. There came a shower of kicks and punches, and the boys scattered. Away flew Pinocchio. The people were astonished to see those tiny legs fly like the wind. They shouted and ran after him. Pinocchio resolved not to be caught. He turned into a side street that led into the open country. A large dog, stretched out upon the ground, was in his way. Pinocchio measured the distance and leaped.

At that very moment the dog sprang up, and hardly knowing how it happened, Pinocchio found himself astride his back. Barking furiously, the animal shot along like a cannon ball. The poor boy felt sure that he was going to break his neck and prayed for safety. On they rushed. The dog jumped over rocks and ditches as if he had done nothing in all his life but carry marionettes on his back.

“Is it possible that he is a horse-dog?” thought Pinocchio. “If he is, I shall ride him always, and when I return home, I shall present him to my father. My companions will die of envy when they see me riding to school like a gentleman. I shall make him a saddle like those I saw on the circus horses, and a pair of silver stirrups. A saddle is really necessary, because it is very uncomfortable to ride in this way.”

The came to a deep gully and the dog prepared to make the leap. Pinocchio muttered to himself: “This is the end. If I cross this in safety, I will surely return home and go to school.”

There was a leap, and a plunge into the black, empty air. When he opened his eyes, he found himself lying at the bottom of a precipice in total darkness. How long had he been in the air? The marionette did not know. He remembered only that while flying down he had heard a familiar voice call, “Pinocchio! Pinocchio! Pinocchio!”

“Farewell to the world and to Africa,” said the marionette. “Wooden marionettes will never learn. Here I shall stay forever. It serves me right.”

“If I get out of this prison alive, it will be the greatest wonder I have ever known.” Pinocchio sat in the spot where he had fallen. He now began to suffer from thirst. There had been a great deal of excitement, and his throat was parched. He would have given anything for a sip of the water he had so carelessly left in the middle of the street only a little while before.

“I don’t want to die here,” he said. “I must get up and walk.”

So saying, he moved slowly about, groping with his hands and feet as if he were playing blindman’s buff. The ground was soft, and the air seemed fresh. In fact, it was not so bad as he had at first thought. Only four things worried him,—darkness, hunger, thirst, and fear. Aside from these he was safe and sound.

He had gone but a short distance through the darkness when suddenly he thought he heard a faint murmur. He saw a gleam of light. The blood rushed through his veins. He walked on. The sound became clearer, and the light grew brighter. At length Pinocchio found himself in a cave lighted by soft rays. The murmuring sound was caused by a small stream of water coming out from a high rock and forming a little waterfall. Pinocchio rushed toward the rocks, opened his mouth wide like a funnel, and drank his fill.

“I shall not die of thirst,” said the marionette. “Unfortunately, I am still hungry. What a fate is mine! Why can we not live without eating? Some day I am going to find a way. If I succeed, I shall teach the poor people to live without food as I do. How happy they will be!” Meanwhile he looked about for a means of escape. Soon he discovered the hole that lighted the cave, and walked out once more under the open sky.

He saw nothing but rocks and sand; rocks that shone like mirrors, and sand that burned like fire. He walked on very sadly, without knowing where. Presently he found himself upon a hill, from which he could see a vast plain crossed by a wide highway. A long line of people and camels were on the march, but how strange they looked! They were going along with heads down and feet up. At first the marionette was filled with a strong desire to laugh; then he became frightened and rubbed his eyes, doubting what they told him.

“Am I dreaming?” he said to himself.

The line continued its march, and he distinctly heard the people laugh and joke as they all sat upside down on the backs of the inverted camels.

“I was not prepared for this! What a strange way of traveling they have in Africa! Maybe I too am walking on my head!” and he touched himself to make sure that his head was in its proper place.

Meanwhile the caravan passed on, and Pinocchio stood still, his eyes fixed upon the camels as they disappeared at the turning of the road. The only thing left for him to do was to follow them.

“Either on my head or on my feet I shall surely arrive somewhere! I do not believe that all those people will walk on air forever. Sometime or other they will stop to eat. I shall be there to help them.”

As he spoke the marionette started forward, walking rapidly in the hot sun.

In half an hour he had caught up with the topsy-turvy caravan. It had stopped at a large well, which was filled with clear, cool water. The people were laughing and talking as if they were at home. They were all as happy as they could be.

Pinocchio could not understand it. Had these people really stood on their heads? What had happened to them? There was something wrong. He had certainly seen them traveling in that strange fashion. However, a marionette who is hungry and thirsty does not worry long about things he cannot explain. He was there, and the people were eating and drinking.

“What a fool I am! If their heads were upside down, they could neither eat nor drink. Surely they will not refuse me a little water, and perhaps as they are familiar with Africa, I may discover in talking with them where the mines of gold and precious stones are to be found.”

So saying, Pinocchio moved toward an old man who was sitting with a pipe in his mouth. He had finished his meal and was enjoying a smoke. The marionette took off his hat and said, “Pardon me, sir; what time is it?”

The old man’s answer came in a volume of smoke.

“Ask the sun, my boy. He will tell you.”

“Thank you!” said Pinocchio, a little taken aback by this reception, and he moved on toward a woman with a baby on her shoulders.

“Madam, will you please tell me if I am on the right road to—”

“The world is wide,” broke in the woman.

“And long too,” thought the marionette. “How polite these Africans are!”

Of course, the marionette was a stupid fellow. He was a little ashamed to beg for food, and had only asked these questions so that the people might notice him and perhaps offer him food and water. An ordinary boy would have asked for what he wanted, but the blockhead was too proud.

He was about to go on when the baby began to wave its arms, and to shout, “I want it! I want it!”

Can you guess what it wanted? Pinocchio’s nose! The child reached out its hands, and cried and kicked in trying to get hold of it.

The whole caravan looked toward the spot. A group of children gathered about them. Even the camels lifted their heads to see what was the matter.

The mother was distressed because the child’s screams and kicks continued. She asked Pinocchio to let it touch his nose. His pride was hurt, but thinking it best to humor the child, he went closer and allowed his nose to be touched and squeezed and pulled until the baby was perfectly happy and satisfied. The good woman laughed, and thanked Pinocchio by offering him some bread and milk.

Pinocchio buried his face in the milk and ate the bread. There was no doubt of his hunger. The others offered him fruit and cake. He was pleased. Africa, after all, was a country where one could live. His hunger satisfied, he did what marionettes usually do,—talked about himself. In a short time all the people knew who he was and why he had come to Africa. The old man with the pipe asked him, “Who told you that here in Africa there is so much gold?”

“Who told me? He who knows told me!”

“But are you sure that he did not wish to deceive you?”

“Deceive me?” replied the marionette, “My dear sire, to deceive me one must have a good—” and he touched his forehead with his forefinger as much as to say that within lay a great brain. “Before leaving home I studied so much that the teacher feared I should ruin my health.”

“Very well,” replied the old man, “let us travel together, for we also are in search of gold and precious stones.”

Pinocchio’s heart beat fast with hope. At last there was some one to help him in his search. He could scarcely control himself enough to say: “Willingly, most willingly! I have no objections. Suit yourselves.”

The camels, refreshed by the large amount of water they had taken, stood up, proud of their loads. Even the donkey brayed. Yes, there was a donkey! And this fact displeased Pinocchio. He had for a long time felt a great dislike for these animals. In fact, he had once been a donkey, and his dislike was a natural one.

The donkey did not carry any load, and for that reason the marionette was asked to ride on its back. He hesitated. It was stupid to ride a donkey, and he would have preferred to walk, but he did not like to seem rude to the good people, and up he mounted.

They traveled all day along the narrow road which gradually wound around the slope of a mountain. The old man rode by the side of Pinocchio, asking him many questions about the studies he had taken up to prepare himself for this trip to Africa.

The marionette talked a great deal, and as might have been expected, made many blunders. He began to think that his companions were very simple, and that in Africa one could tell any kind of lie without being discovered. He even went so far as to assure the old man that he knew the very spot where they could find gold and diamonds, and ended by saying that within a week they should all be men of great wealth.

“You must walk straight ahead,” the saucy marionette was saying, “then to the right, and you will arrive at the bottom of a valley, through which flows a beautiful brook of yellow water. By the side of this brook is a tree, and beneath the tree there is gold in plenty.”

The old man was amazed to hear the tales he told. Pinocchio himself felt ashamed of all these lies. He was afraid his nose would grow as it had done one day at home. But no, it was still its natural size!

“Well!” he thought, “if it has not grown longer this time, it will never grow again, no matter how many lies I tell.”

They went on until they met a second caravan resting at a well. Every one admired Pinocchio, and the old man who had him in charge treated him as if he were his own son.

Pinocchio was greatly pleased. Yet to tell the truth he was worried. Suppose they discovered that he had lied, and that he knew nothing about Africa, or the gold, or the diamonds! What would happen then?

The old man was talking to three or four men of the new caravan. Pinocchio did not like their faces. Now and then they looked toward the marionette with open eyes of astonishment.

Pinocchio pricked up his ears to listen to the good things the old man was saying about him. He felt highly flattered on hearing himself praised for his character, his intelligence, and his ability to eat and drink.

Then the men lowered their voices, and the marionette only now and then caught some stray words.

“How much do you want?”

“Come!” replied the good old man, “between us there should not be so much talk. I cannot give him to you unless you give me twenty yards of English calico, thirty yards of iron wire, and four strings of glass beads.”

“It is too much. It is too much,” replied one.

“They are bargaining for the donkey,” said Pinocchio, and he felt sorry for the poor beast.

“I am sorry for you,” he went on, addressing the donkey, “because you have made me quite comfortable. Now I must give you up and walk.”

“It is too much. It is too much,” the men were saying.

“Yes, yes, all you say is very true,” spoke one in a high voice, “but, after all, he is made of wood.”

“Of wood? Who is made of wood? The donkey?” thought Pinocchio, looking at the animal, which stood still, its ears erect as if it also were listening.

“Here!” put in one of the men, “the bargain is made if you will give him up for an elephant’s tooth; if not, let us talk no more of it.”

The old man was silent. He looked at the marionette, and then with a sigh which came from his heart he said: “You drive a hard bargain! Add at least the horn of a rhinoceros and let us be done with it.”

“Put in the horn!” replied the man, and they shook hands. “You have done well, my friends,” the old man said. “That fellow there,”—and this time pointed directly at Pinocchio,—“that fellow there has some great ideas in his head. He knows a thing or two! He says he knows the exact spot where one may find gold and diamonds.”

Pinocchio was thunderstruck! It was he and not the donkey that had been sold.

“Dogs!” he cried, “farewell. I go from you forever.” And away he leaped as fast as the north wind. They did not even try to follow him. Who could have caught him.

After two hours of hard running, Pinocchio, still angry at the treatment he had received, came to a forest. “It’s better to be a bird in the bushes than a bird in a cage!” he thought.

Although the walk in the forest was refreshing, he began, as usual, to be hungry. The place was very beautiful, but beauty could not satisfy a marionette’s appetite. He looked here and there in the hope that he might see trees loaded with the fruit about which the elephant man had spoken. He saw nothing but branches and leaves, leaves and branches. On he walked. Both the forest and his hunger seemed without end.

Fortunately Pinocchio was very strong. Being made of wood, he could endure a great many hardships. He was sure that his good Fairy would come to help him, so he kept on bravely. He had walked a long way before he saw a large tree, bearing fruit that resembled oranges.

“At last!” he cried aloud. The birds flew away at the sound. Pinocchio climbed over the rocks and up the tree as fast as he could.

“I will eat enough to last for a week!” he said, as he thought of the orange peel his father Geppetto had given him for supper.

He picked the largest of the fruit and put it into his mouth. It was as hard as ivory. He pulled out his penknife, with which he used to sharpen his pencil at school. With great difficulty he cut the fruit in two, to find within only a soft, bitter pulp. Then he tried another and another. All were like the first one, and he gave up trying because he was at length convinced that none of the fruit was fit to eat.

Tired and unhappy, with bowed head and dangling arms, he pushed on slowly, stumbling over rocks, and becoming entangled again and again in the briers. He thought sadly of the disappointments he had met with in Africa.

“It is settled. I am to die of hunger. Where are the delicious fruits and the precious stones? Should I not do better to go home and leave the gold and silver to those who want them?”

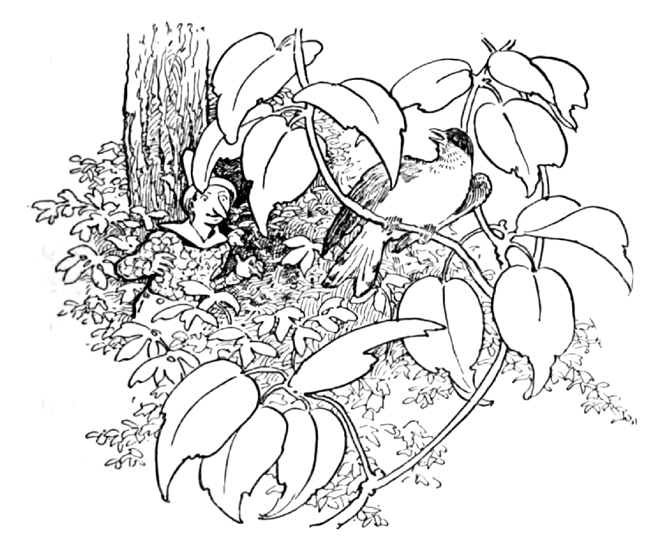

As he went along, thinking over these things, he noticed ahead of him a bird about the size of a canary, which looked at him as if it longed to console him in his misery.

It went on before Pinocchio, flying from one branch to another, stopping when the marionette stopped, and moving every time the marionette moved. Pinocchio said to himself: “Does this dear little bird wish to be eaten? I’ll pluck its feathers, stick a twig through it, put it in the sun, and in half an hour it will be cooked and ready to eat.”

While the hungry marionette was giving himself up to this thought, the bird began to sing,

“Pinocchio, my dear,

If you would honey eat,

Come closer to me here,

And you will find a treat.”

Imagine Pinocchio’s surprise! He approached the little songster and looked up. Sure enough, there on a branch of a great tree was a beehive.

One would think that Pinocchio would at least stop to thank the bird, but not he! Up the tree he went like a squirrel, while the bees buzzed about him angrily. The marionette laughed.

“Sting away! sting away, brave bees! I am a marionette and made of wood. You may sting me as much as you please.” He thrust his hand into the hive and drew out a handful of sweet honey.

“This time at least I shall not die of hunger.”

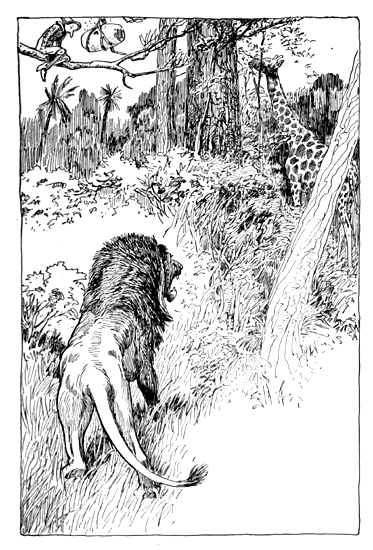

The marionette was on the point of filling his mouth a second time, when he heard a frightful roar directly under his feet. The shock almost tumbled him down headfirst. Had he fallen, how unfortunate it would have been! He would have gone straight into the deep mouth of an African lion which was ready to devour him at one gulp.

“Oh, mercy!” cried the marionette. And the lion gave another dreadful roar which seemed to say: “Mercy indeed! I have you now, you little thief.”

“Dear lion,” pleaded Pinocchio, “have pity on a poor orphan lad who is nearly starving!”

The lion roared still louder. “Who has given you permission to take what belongs to another without having earned it by useful and honest work? In this world he who does not work must starve.”

“You are right, my dear lion, you are right. I am ready to pay to the last cent for all the honey I eat, but please don’t seem so angry or I shall die of fear.”

Then the lion stopped roaring, and sitting down upon the ground, he looked at the marionette as if to say: “Well, what are you going to do about it? Are you coming down or not?”

“Listen, my dear lion,” answered Pinocchio; “so long as you stay there, I shall not come down. If you want me to go away and leave the honey, remove yourself a hundred miles or so, and then I will obey you.”

The lion did not move.

For almost an hour Pinocchio sat glued to the tree, not daring to eat the honey or to come down to the waiting lion. The hot rays of the sun beat upon him. He felt that he must die, for hunger, fear, and heat seemed ready to destroy him.

“Surely there must be away out of this,” he thought. “That lion must have in him some spark of kindness. He has made up his mind to keep me company, and perhaps it is my duty to thank him.”

Then the marionette raised his hand to ask permission to speak. It would have been better had he kept still.

At this gesture the lion uttered a roar so loud that it shook the whole forest. He began to lash the ground with his tail, sending up a cloud of dust that nearly choked the marionette, and repeating all the while in lion language, “If you move hand or foot, you will die!”

Pinocchio sat still. Another hour passed in silence. Pinocchio still suffered from the heat and from hunger. Both honey and shade were within easy reach, and he could enjoy neither.

“What an obstinate beast!” he muttered. “How stupid he is to wait there! There is enough room in the forest for us both.”

But the lion did not move, and Pinocchio’s suffering was great. He was sure now that he was going to die, and he looked sadly at those wooden legs which had carried him through so many adventures. There was the shade, but he could not reach it. There was the honey that must not be touched.

“Eat! eat!” said the honey. “Come! come!” said the shade.

Fortunately a new character now arrived on the scene. A magnificent giraffe came along through the bushes, eating the tender shoots as it approached the spot.

Pinocchio saw the giraffe and recognized it at once from a picture of one he had seen in school. The lion saw it also. What should he do? Continue to watch the marionette, or attack and carry off the giraffe? He decided to take the giraffe. As the animal raised its head to bite off the leaves from a tall acacia, the lion leaped at its throat and killed it. Seizing the body in his powerful jaws, the lion disappeared through the forest, and Pinocchio was left behind to have his fill of honey. He ate as he had never eaten before.

When he could eat no longer he came down from the tree, but how strange he felt! His eyes were dim, and his head began to swim, while his legs went here and there in every direction. He could not even talk clearly.

“African honey plays jokes upon those who eat too much of it!” he seemed to hear some one say. He turned to see who it was that had spoken to him, but no one was there. The next moment he fell heavily to the ground as if he had been knocked down with a club.

“That is what happens to greedy boys!” continued the voice of the little bird who had shown him the honey, but Pinocchio lay fast asleep.

Pinocchio had slept for hours when he was aroused by strange sounds. Were these the voices of human beings.

“Yah! Yah! Hoi! Hoi! Uff! Uff!”

What could it possibly be? The marionette opened an eye, but quickly shut it again when he saw a number of coal-black faces turned toward him.

“What do these ugly people want of me?” he asked himself, as he lay there perfectly still.

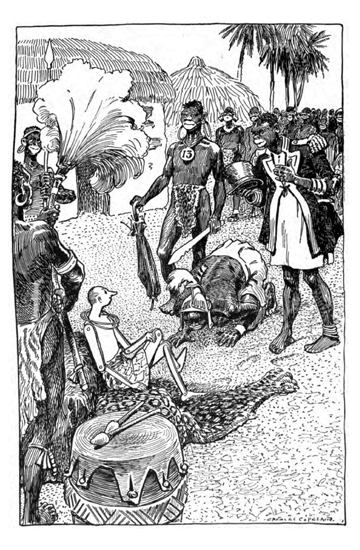

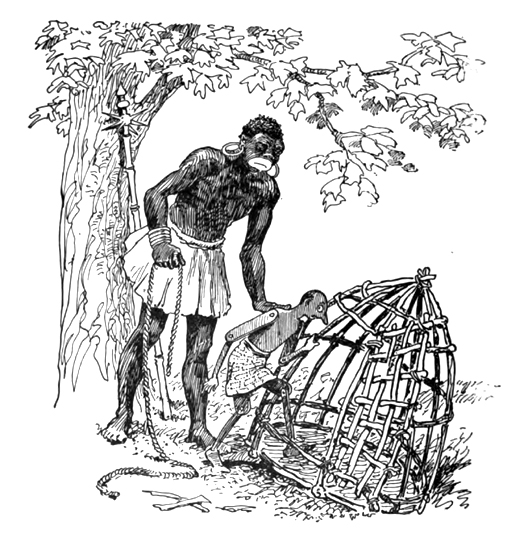

When Pinocchio next opened his eyes he saw to his great surprise that the men had formed a circle about him. At their chief’s command they began to dance. It was all so funny that Pinocchio could hardly keep from laughing. Then the chief made a sign, at which the savages advanced toward the marionette, took him up by his arms and legs, and started away with him.

“This is not so bad,” thought the marionette.

After a time his bearers laid him gently upon the ground and commenced to examine him. Pinocchio decided to make believe he was dead.

For that reason he kept his eyes shut tightly and lay still.

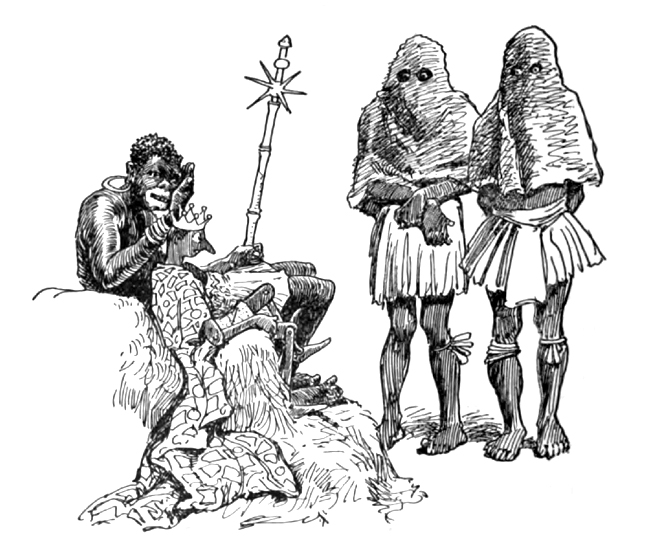

Suddenly there was a great noise. He was startled. Opening one eye, he saw approaching a chief followed by a crowd of attendants. Judging from the manner in which the new arrivals were received, they were persons of high rank. At their approach the savages knelt down, raised their hands high in the air, and bent their foreheads to the ground.

A man stepped out from the ranks and came toward Pinocchio. He examined the marionette from head to foot, while all the others looked on in silence.

When the examination was over the marionette hoped to be left in peace, but another approached him and went through the same performance. Then came a third, a fourth, a fifth, and so on.

Pinocchio was somewhat tired of this. As the last one came up he muttered, “Now I shall see what they are going to do with me.”

The man who had first examined Pinocchio now approached him again, and calling the bearers, said, in a tongue which, curiously enough, the marionette understood, “Turn the little animal over!”

Upon hearing himself called an animal, Pinocchio was seized with a mad desire to give his tormentor a kick, but he thought better of it.

The bearers advanced, took the marionette by the shoulders, and rolled him over.

“Easy! easy! this bed is not too soft,” Pinocchio said to himself.

A second examination followed, and then another command, “Roll him over again!”

“What do you take me for,—a top?” muttered the marionette in a burst of rage. But he pricked up his ears when the man who had been rolling him over turned to another and said, “Your majesty!”

“Indeed!” thought Pinocchio, “we are not dealing with ordinary persons! We are beginning to know great people. Let me hear what he has to say about me to his black majesty,” and the marionette listened with the deepest attention.

“Your majesty, my knowledge of the noble art of cooking assures me that this creature”—and he gave Pinocchio a kick—“is an animal of an extinct race. It has been turned into wood, carried by the water to the beach, and then brought here by the wind.”

“Not so bad for a cook,” thought Pinocchio. He felt half inclined to strike out and hit the nose of the wise savage, who had again knelt down to examine him.

“Your majesty,” continued the cook, “this little animal is dead, because if it were not dead—”

“It would be alive,” Pinocchio muttered. “What a beast! How stupid!”

“Because if it were not dead, it would not be so hard. To conclude, had it not been made of wood, I could have cooked it for your majesty’s dinner.”

Pinocchio said to himself: “Listen to this black rascal! Eaten alive! What kind of country have I fallen into? What vulgar people! It’s lucky for me that I am made of wood!”

His majesty then commanded that as the animal was not good to eat it should be buried.

Immediately three or four of the men began to dig a hole, while the unfortunate marionette, half dead with fright, tried to form some plan of escape. The time passed. The hole was dug, and the poor fellow could not think of any plan. Run away! But how? And if they found out that he was alive would he not be cooked and eaten? The marionette did not know what to do.

In the meantime two men had raised him from the ground and stood ready to throw him into the hole. Then in spite of himself, the marionette began to shout at the top of his lungs: “Stop! Stop! I will not be buried alive! Help! Help! My good Fatina!—Fatina!—my Fatina! Help!”

At the first shout the two men who were holding him let him fall to the ground and started off in a great fright. All the others followed their example.

“What funny people!” said Pinocchio. “If I had known that they would all run away like this, I should not have been so uneasy. However, I really do not know why I have come here. If I only knew where to find diamonds and gold, it would not be so hard. I might return home to my father, for who knows how much he is suffering because I am not there!”

At that moment he would have given up the whole trip, but he was too stupid to keep an idea in his head for more than a few seconds. Another thought flashed across his mind, and he forgot his poor father.

“If these people run away, it means that they are afraid, and if they are afraid, it means that they have no courage. Now then, I, being very brave, may in a short time come to rule over everything in Africa. Perhaps—who knows!—I may become a king or an emperor!”

Pinocchio, you lazy dreamer, are you never going to learn wisdom? Only a blockhead like you could be so foolish. A wooden emperor, indeed!

Filled with these hopes and forgetting his fright, Pinocchio set boldly forth without the least alarm at the difficulties of the journey. He was going merrily along, dreaming of all the great things he would do as emperor of Africa, when at a turn in the road there came flying after him a volley of stones. Had any struck him he would have been killed. Astonished and frightened at this strange turn of affairs, he glanced around, but saw no one. He looked up at the trees, and then from right to left, but nobody was in sight.

“This is pleasant!” exclaimed the marionette. “Have those pebbles fallen from the sky?” And he started to go on his way.

He had taken only a few steps, when a second discharge drove him to the shelter of a large tree. Thence he looked carefully in the direction from which the stones continued to come. To his surprise he discovered among the bushes and twigs a large number of monkeys.

“Well! What is this?” cried the marionette. “Those rogues must not be allowed to play such mean tricks. I had better be on my guard.”

He picked up a stout stick lying on the ground near by. To his amazement, the monkeys threw away the stones and began to pick up sticks likewise.

“I hope I shall get through this safely!” thought Pinocchio. He raised his stick and threatened the whole army of monkeys.

The monkeys, as if obeying his command, raised their sticks and held them erect, imitating exactly the action of the marionette. Then Pinocchio lowered his stick, and the monkeys lowered theirs. Again Pinocchio lifted his stick as high as he could, and the monkeys raised theirs, holding them stiffly like soldiers on drill.

“Arms rest!” cried Pinocchio.

All the monkeys, imitating the marionette, lowered their sticks in perfect order, just as soldiers do at the officer’s command.

“That’s a good idea,” thought Pinocchio, “I might become the leader of the monkeys, and within a month conquer all Africa.” And he laughed at the joke.

The monkeys looked straight at him, standing erect and in line waiting for further orders.

“Ah! you wish to follow me!” said the marionette. “This might suit your taste, but not mine, thank you! I will give you marching orders. Then I shall be left in peace.”

Accordingly Pinocchio, who was determined to get away from these annoying beasts, moved two steps forward. The monkeys advanced two steps also. Then he took three steps to the rear, and the monkeys went back three steps.

“At—tention!” and facing about quickly, he started to run. All the monkeys also turned, and began to run in the direction opposite to that taken by the marionette. Pinocchio, laughing at his own cunning, went his way, only now and then turning to watch the dark forms as they disappeared in the distance.

“They all run away in this country,” he said to himself, and he too ran on, fearing that the worthy beasts would return for further orders.

“If these people are such cowards that they run at the sound of my voice, in a few days I shall be master of all Africa. I shall be a great man. However, this is a country of hunger and thirst and fatigue. I must find a place where I can rest a little before I begin my career of conquest.”

Fortune now seemed to favor Pinocchio. Not far off he thought he saw a group of huts at the foot of a hill. He felt that besides getting rest and shelter, he might also find something to eat. Greedy marionette!

As he approached he was struck by the strangeness of these buildings. They looked like little towers topped with domes. He went along wondering what race of people lived in houses built without windows or doors. He saw no one, and he was filled with a sort of fear.

“Shall I go on or not?” he mused. “Perhaps it would be best to call out, Some one will show me where to go for food and shelter.”

“Hello there!” he said in a low voice. No one answered.

“Hello there!” repeated the marionette a little louder. But there was no answer.

“They are deaf, or asleep, or dead!” concluded the marionette, after calling out at the top of his voice again and again.

Then he thought it might be a deserted village, and he entered bravely between the towers. There was no one to be seen. As he stretched out his tired limbs on the ground he murmured. “Since it is useless to think of eating, I may at least rest.” And in a few minutes he was sound asleep.

He dreamed that he was being pulled along by an army of small insects that resembled ants. It seemed to him that he was making every effort to stop them, but he could not succeed. They dragged and rolled him down a slope toward a frightful precipice, over which he must fall. It even seemed as if they had entered his mouth by hundreds, busying themselves in tearing out his tongue. It served him right, too, because his tongue had made many false promises and caused everybody much suffering.

“You will never tell any more lies!” the ants seemed to say.

Then the marionette awoke with a struggle and a cry of fear. His dream was a reality. He was covered with ants. He brushed them off his face, his arms, his legs,—in short, his whole body. They had tortured him for four or five hours, and only the fact that he was made of very hard wood had saved his life.

“Thanks to my strong constitution.” thought the marionette, “I am as good as new.”

Pinocchio now found himself in a dense growth of shrubbery which made his progress difficult. He pushed on among the thorny plants. They would have stopped any one but a wooden marionette. His clothes were torn, to be sure, but he did not mind that.

“Soon I shall have a suit that will make me look like a prince. Goods of the best quality, and tailoring that has never been equaled! The gold, the silver, and the diamonds must be found.” And he went on at a brisk gait as if he had been on the highway.

Trees, shrubs, underbrush,—nothing else! The scene would have grown tiresome had it not been for a swarm of butterflies of the most beautiful and brilliant colors. They flew here and there, now letting themselves be carried by the wind, now hovering about in search of the flowers hidden in the thick foliage.

From time to time a hare would run between Pinocchio’s feet, and after a few bounds would turn sharply around to stare at him with curious eyes, as much as to say that a marionette was a comical sight. Young monkeys peeped through the leaves, laughed at him, and then scampered away.

Pinocchio walked along fearlessly, caring little for what went on around him, and thinking only of the treasures for which he was seeking.

On and on he walked until at length he found himself at the edge of a vast plain. He gave a great sigh of relief. The long march through the woods had tired him. However, he kept his eyes open, now and then looking down at his feet to see if any precious stones were lying about. Presently his attention was drawn to a great hole or nest, in which he saw some white objects shaped like hen’s eggs, but considerably larger than his head.

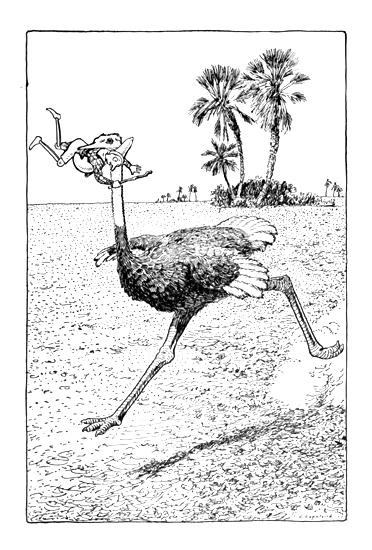

Curious to see whether or not he could lift one, Pinocchio approached the nest. Just then he heard a frightful noise behind him.