| Previous Part | Main Index | Next Part |

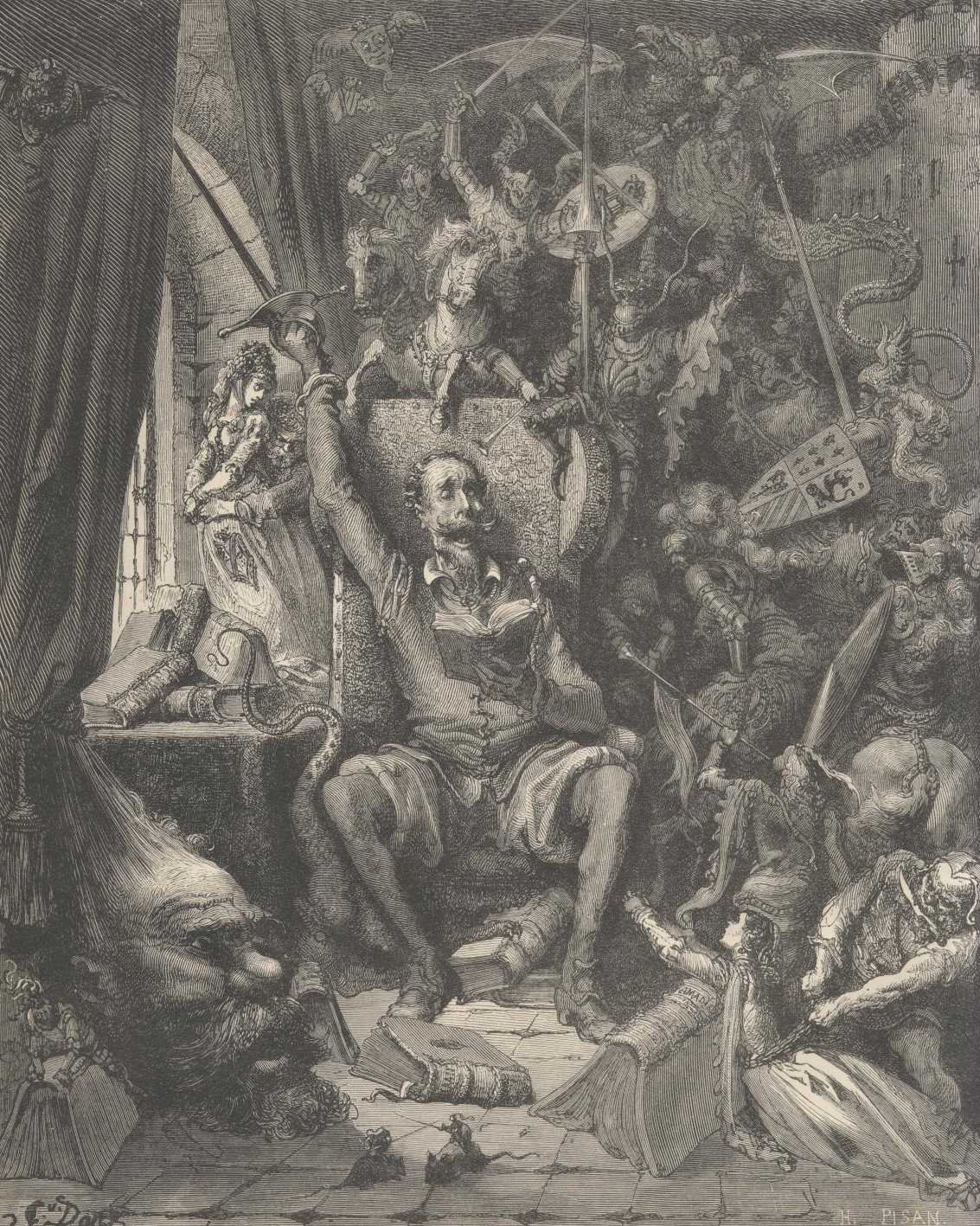

The book cover and spine above and the images which follow were not part of the original Ormsby translation—they are taken from the 1880 edition of J. W. Clark, illustrated by Gustave Dore. Clark in his edition states that, "The English text of 'Don Quixote' adopted in this edition is that of Jarvis, with occasional corrections from Motteaux." See in the introduction below John Ormsby's critique of both the Jarvis and Motteaux translations. It has been elected in the present Project Gutenberg edition to attach the famous engravings of Gustave Dore to the Ormsby translation instead of the Jarvis/Motteaux. The detail of many of the Dore engravings can be fully appreciated only by utilizing the "Enlarge" button to expand them to their original dimensions. Ormsby in his Preface has criticized the fanciful nature of Dore's illustrations; others feel these woodcuts and steel engravings well match Quixote's dreams. D.W.

CHAPTER XXI IN WHICH CAMACHO'S WEDDING IS CONTINUED, WITH OTHER DELIGHTFUL INCIDENTS

While Don Quixote and Sancho were engaged in the discussion set forth the last chapter, they heard loud shouts and a great noise, which were uttered and made by the men on the mares as they went at full gallop, shouting, to receive the bride and bridegroom, who were approaching with musical instruments and pageantry of all sorts around them, and accompanied by the priest and the relatives of both, and all the most distinguished people of the surrounding villages. When Sancho saw the bride, he exclaimed, "By my faith, she is not dressed like a country girl, but like some fine court lady; egad, as well as I can make out, the patena she wears rich coral, and her green Cuenca stuff is thirty-pile velvet; and then the white linen trimming—by my oath, but it's satin! Look at her hands—jet rings on them! May I never have luck if they're not gold rings, and real gold, and set with pearls as white as a curdled milk, and every one of them worth an eye of one's head! Whoreson baggage, what hair she has! if it's not a wig, I never saw longer or fairer all the days of my life. See how bravely she bears herself—and her shape! Wouldn't you say she was like a walking palm tree loaded with clusters of dates? for the trinkets she has hanging from her hair and neck look just like them. I swear in my heart she is a brave lass, and fit 'to pass over the banks of Flanders.'"

Don Quixote laughed at Sancho's boorish eulogies and thought that, saving his lady Dulcinea del Toboso, he had never seen a more beautiful woman. The fair Quiteria appeared somewhat pale, which was, no doubt, because of the bad night brides always pass dressing themselves out for their wedding on the morrow. They advanced towards a theatre that stood on one side of the meadow decked with carpets and boughs, where they were to plight their troth, and from which they were to behold the dances and plays; but at the moment of their arrival at the spot they heard a loud outcry behind them, and a voice exclaiming, "Wait a little, ye, as inconsiderate as ye are hasty!" At these words all turned round, and perceived that the speaker was a man clad in what seemed to be a loose black coat garnished with crimson patches like flames. He was crowned (as was presently seen) with a crown of gloomy cypress, and in his hand he held a long staff. As he approached he was recognised by everyone as the gay Basilio, and all waited anxiously to see what would come of his words, in dread of some catastrophe in consequence of his appearance at such a moment. He came up at last weary and breathless, and planting himself in front of the bridal pair, drove his staff, which had a steel spike at the end, into the ground, and, with a pale face and eyes fixed on Quiteria, he thus addressed her in a hoarse, trembling voice:

"Well dost thou know, ungrateful Quiteria, that according to the holy law we acknowledge, so long as live thou canst take no husband; nor art thou ignorant either that, in my hopes that time and my own exertions would improve my fortunes, I have never failed to observe the respect due to thy honour; but thou, casting behind thee all thou owest to my true love, wouldst surrender what is mine to another whose wealth serves to bring him not only good fortune but supreme happiness; and now to complete it (not that I think he deserves it, but inasmuch as heaven is pleased to bestow it upon him), I will, with my own hands, do away with the obstacle that may interfere with it, and remove myself from between you. Long live the rich Camacho! many a happy year may he live with the ungrateful Quiteria! and let the poor Basilio die, Basilio whose poverty clipped the wings of his happiness, and brought him to the grave!"

And so saying, he seized the staff he had driven into the ground, and leaving one half of it fixed there, showed it to be a sheath that concealed a tolerably long rapier; and, what may be called its hilt being planted in the ground, he swiftly, coolly, and deliberately threw himself upon it, and in an instant the bloody point and half the steel blade appeared at his back, the unhappy man falling to the earth bathed in his blood, and transfixed by his own weapon.

His friends at once ran to his aid, filled with grief at his misery and sad fate, and Don Quixote, dismounting from Rocinante, hastened to support him, and took him in his arms, and found he had not yet ceased to breathe. They were about to draw out the rapier, but the priest who was standing by objected to its being withdrawn before he had confessed him, as the instant of its withdrawal would be that of this death. Basilio, however, reviving slightly, said in a weak voice, as though in pain, "If thou wouldst consent, cruel Quiteria, to give me thy hand as my bride in this last fatal moment, I might still hope that my rashness would find pardon, as by its means I attained the bliss of being thine."

Hearing this the priest bade him think of the welfare of his soul rather than of the cravings of the body, and in all earnestness implore God's pardon for his sins and for his rash resolve; to which Basilio replied that he was determined not to confess unless Quiteria first gave him her hand in marriage, for that happiness would compose his mind and give him courage to make his confession.

Don Quixote hearing the wounded man's entreaty, exclaimed aloud that what Basilio asked was just and reasonable, and moreover a request that might be easily complied with; and that it would be as much to Senor Camacho's honour to receive the lady Quiteria as the widow of the brave Basilio as if he received her direct from her father.

"In this case," said he, "it will be only to say 'yes,' and no consequences can follow the utterance of the word, for the nuptial couch of this marriage must be the grave."

Camacho was listening to all this, perplexed and bewildered and not knowing what to say or do; but so urgent were the entreaties of Basilio's friends, imploring him to allow Quiteria to give him her hand, so that his soul, quitting this life in despair, should not be lost, that they moved, nay, forced him, to say that if Quiteria were willing to give it he was satisfied, as it was only putting off the fulfillment of his wishes for a moment. At once all assailed Quiteria and pressed her, some with prayers, and others with tears, and others with persuasive arguments, to give her hand to poor Basilio; but she, harder than marble and more unmoved than any statue, seemed unable or unwilling to utter a word, nor would she have given any reply had not the priest bade her decide quickly what she meant to do, as Basilio now had his soul at his teeth, and there was no time for hesitation.

On this the fair Quiteria, to all appearance distressed, grieved, and repentant, advanced without a word to where Basilio lay, his eyes already turned in his head, his breathing short and painful, murmuring the name of Quiteria between his teeth, and apparently about to die like a heathen and not like a Christian. Quiteria approached him, and kneeling, demanded his hand by signs without speaking. Basilio opened his eyes and gazing fixedly at her, said, "O Quiteria, why hast thou turned compassionate at a moment when thy compassion will serve as a dagger to rob me of life, for I have not now the strength left either to bear the happiness thou givest me in accepting me as thine, or to suppress the pain that is rapidly drawing the dread shadow of death over my eyes? What I entreat of thee, O thou fatal star to me, is that the hand thou demandest of me and wouldst give me, be not given out of complaisance or to deceive me afresh, but that thou confess and declare that without any constraint upon thy will thou givest it to me as to thy lawful husband; for it is not meet that thou shouldst trifle with me at such a moment as this, or have recourse to falsehoods with one who has dealt so truly by thee."

While uttering these words he showed such weakness that the bystanders expected each return of faintness would take his life with it. Then Quiteria, overcome with modesty and shame, holding in her right hand the hand of Basilio, said, "No force would bend my will; as freely, therefore, as it is possible for me to do so, I give thee the hand of a lawful wife, and take thine if thou givest it to me of thine own free will, untroubled and unaffected by the calamity thy hasty act has brought upon thee."

"Yes, I give it," said Basilio, "not agitated or distracted, but with unclouded reason that heaven is pleased to grant me, thus do I give myself to be thy husband."

"And I give myself to be thy wife," said Quiteria, "whether thou livest many years, or they carry thee from my arms to the grave."

"For one so badly wounded," observed Sancho at this point, "this young man has a great deal to say; they should make him leave off billing and cooing, and attend to his soul; for to my thinking he has it more on his tongue than at his teeth."

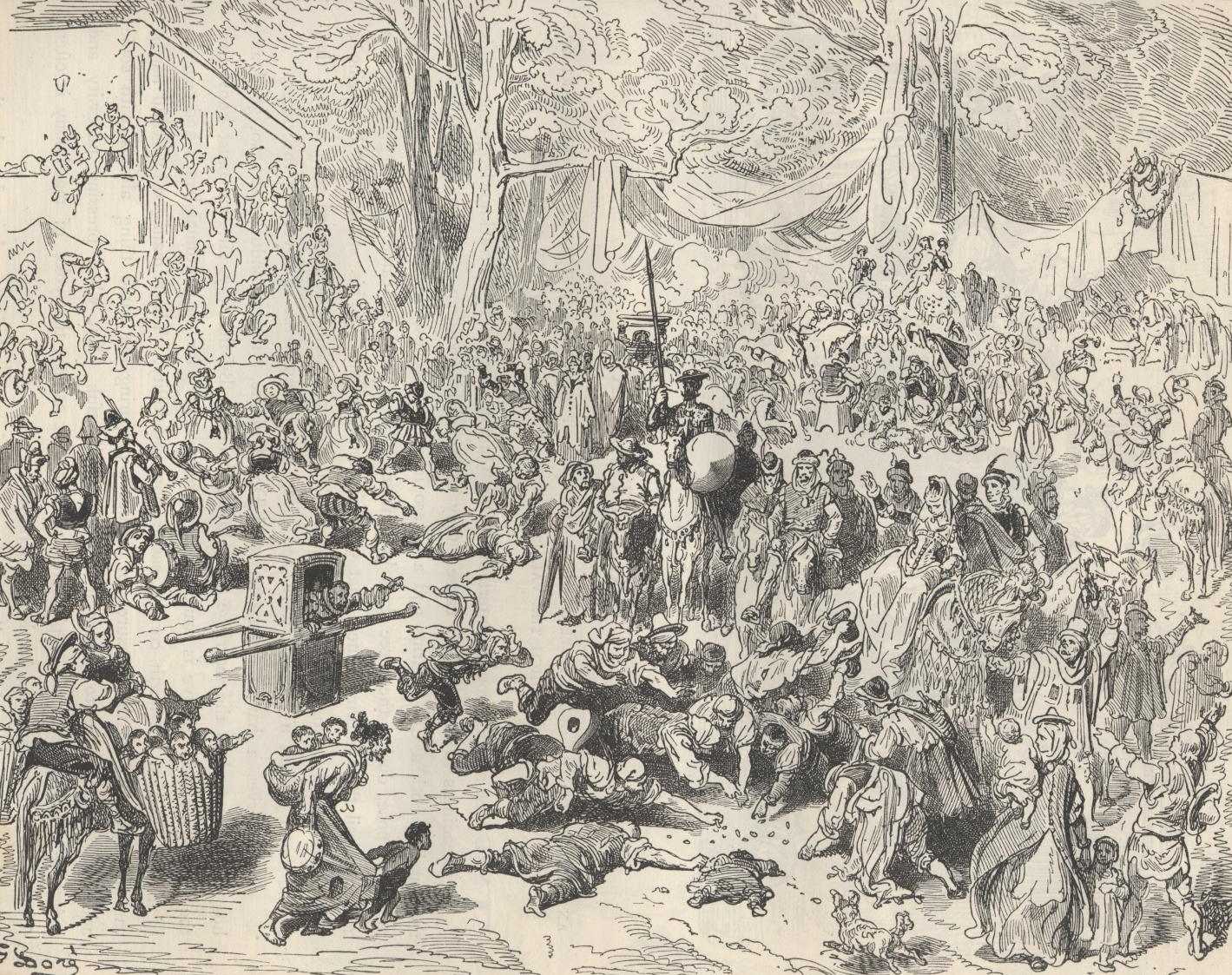

Basilio and Quiteria having thus joined hands, the priest, deeply moved and with tears in his eyes, pronounced the blessing upon them, and implored heaven to grant an easy passage to the soul of the newly wedded man, who, the instant he received the blessing, started nimbly to his feet and with unparalleled effrontery pulled out the rapier that had been sheathed in his body. All the bystanders were astounded, and some, more simple than inquiring, began shouting, "A miracle, a miracle!" But Basilio replied, "No miracle, no miracle; only a trick, a trick!" The priest, perplexed and amazed, made haste to examine the wound with both hands, and found that the blade had passed, not through Basilio's flesh and ribs, but through a hollow iron tube full of blood, which he had adroitly fixed at the place, the blood, as was afterwards ascertained, having been so prepared as not to congeal. In short, the priest and Camacho and most of those present saw they were tricked and made fools of. The bride showed no signs of displeasure at the deception; on the contrary, hearing them say that the marriage, being fraudulent, would not be valid, she said that she confirmed it afresh, whence they all concluded that the affair had been planned by agreement and understanding between the pair, whereat Camacho and his supporters were so mortified that they proceeded to revenge themselves by violence, and a great number of them drawing their swords attacked Basilio, in whose protection as many more swords were in an instant unsheathed, while Don Quixote taking the lead on horseback, with his lance over his arm and well covered with his shield, made all give way before him. Sancho, who never found any pleasure or enjoyment in such doings, retreated to the wine-jars from which he had taken his delectable skimmings, considering that, as a holy place, that spot would be respected.

"Hold, sirs, hold!" cried Don Quixote in a loud voice; "we have no right to take vengeance for wrongs that love may do to us: remember love and war are the same thing, and as in war it is allowable and common to make use of wiles and stratagems to overcome the enemy, so in the contests and rivalries of love the tricks and devices employed to attain the desired end are justifiable, provided they be not to the discredit or dishonour of the loved object. Quiteria belonged to Basilio and Basilio to Quiteria by the just and beneficent disposal of heaven. Camacho is rich, and can purchase his pleasure when, where, and as it pleases him. Basilio has but this ewe-lamb, and no one, however powerful he may be, shall take her from him; these two whom God hath joined man cannot separate; and he who attempts it must first pass the point of this lance;" and so saying he brandished it so stoutly and dexterously that he overawed all who did not know him.

But so deep an impression had the rejection of Quiteria made on Camacho's mind that it banished her at once from his thoughts; and so the counsels of the priest, who was a wise and kindly disposed man, prevailed with him, and by their means he and his partisans were pacified and tranquillised, and to prove it put up their swords again, inveighing against the pliancy of Quiteria rather than the craftiness of Basilio; Camacho maintaining that, if Quiteria as a maiden had such a love for Basilio, she would have loved him too as a married woman, and that he ought to thank heaven more for having taken her than for having given her.

Camacho and those of his following, therefore, being consoled and pacified, those on Basilio's side were appeased; and the rich Camacho, to show that he felt no resentment for the trick, and did not care about it, desired the festival to go on just as if he were married in reality. Neither Basilio, however, nor his bride, nor their followers would take any part in it, and they withdrew to Basilio's village; for the poor, if they are persons of virtue and good sense, have those who follow, honour, and uphold them, just as the rich have those who flatter and dance attendance on them. With them they carried Don Quixote, regarding him as a man of worth and a stout one. Sancho alone had a cloud on his soul, for he found himself debarred from waiting for Camacho's splendid feast and festival, which lasted until night; and thus dragged away, he moodily followed his master, who accompanied Basilio's party, and left behind him the flesh-pots of Egypt; though in his heart he took them with him, and their now nearly finished skimmings that he carried in the bucket conjured up visions before his eyes of the glory and abundance of the good cheer he was losing. And so, vexed and dejected though not hungry, without dismounting from Dapple he followed in the footsteps of Rocinante.

| Previous Part | Main Index | Next Part |