The Project Gutenberg EBook of Old Calabria, by Norman Douglas This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Old Calabria Author: Norman Douglas Posting Date: June 16, 2013 [EBook #7385] Release Date: January, 2005 First Posted: April 23, 2003 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OLD CALABRIA *** Produced by Eric Eldred

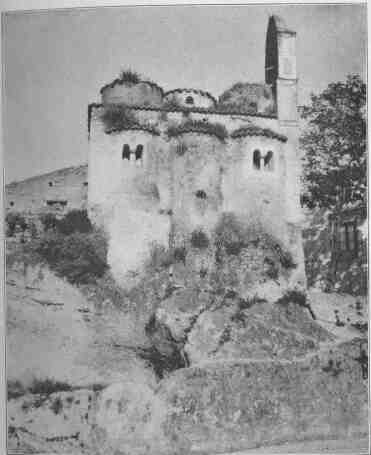

Tower at

Manfredonia

PAGE

I. SARACEN LUCERA

I

II. MANFRED'S TOWN

10

III. THE ANGEL OF

MANFREDONIA 17

IV. CAVE-WORSHIP

23

V. LAND OF HORACE

31

VI. AT VENOSA

37

VII. THE BANDUSIAN

FOUNT 41

VIII. TILLERS OF THE

SOIL 47

IX. MOVING SOUTHWARDS

62

X. THE FLYING MONK

71

XI. BY THE INLAND SEA

77

XII. MOLLE TARENTUM

87

XIII. INTO THE JUNGLE

95

XIV. DRAGONS

100

XV. BYZANTINISM

105

XVI. REPOSING AT

CASTROVILLARI 117

XVII. OLD MORANO

128

XVIII. AFRICAN

INTRUDERS 134

XIX. UPLANDS OF

POLLINO 142

XX. A MOUNTAIN

FESTIVAL 151

XXI. MILTON IN

CALABRIA l60

XXII. THE "GREEK "

SILA 172

XXIII. ALBANIANS AND

THEIR COLLEGE 181

XXIV. AN ALBANIAN SEER

188

XXV. SCRAMBLING TO

LONGOBUCCO 193

XXVI. AMONG THE

BRUTTIANS 202

XXVII. CALABRIAN

BRIGANDAGE • 211

XXVIII. THE GREATER

SILA 217

XXIX. CHAOS

228

XXX. THE SKIRTS OF

MONTALTO 240

v

Contents

PAGE

XXXI. SOUTHERN

SAINTLINESS 247

XXXII. ASPROMONTE, THE

CLOUD-GATHERER 269

XXXIII. MUSOLINO AND

THE LAW 2J5

XXXIV. MALARIA

281

XXXV. CAULONIA TO

SERRA 288

XXXVI. MEMORIES OF

GISSING 296

XXXVII. COTRONE

303

XXXVIII. THE SAGE OF

CROTON 309

XXXIX. MIDDAY AT

PETELIA 314

XL. THE COLUMN

318

INDEX 323

LIST OF

ILLUSTRATIONS

TOWER AT MANFREDONIA

Frontispiece

LION OF LUCERA Facing

page 4

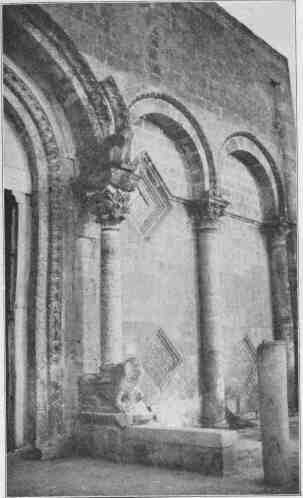

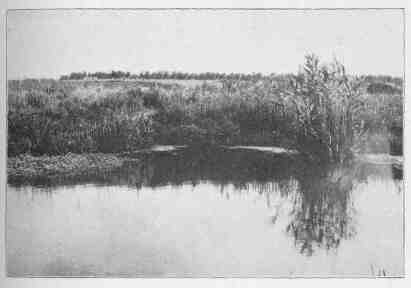

AT SIPONTUM

30

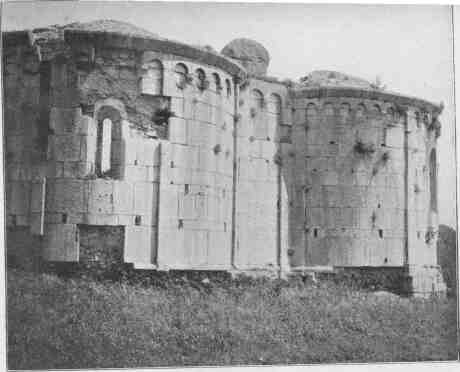

RUIN OF TRINITÀ

: EAST FRONT 38

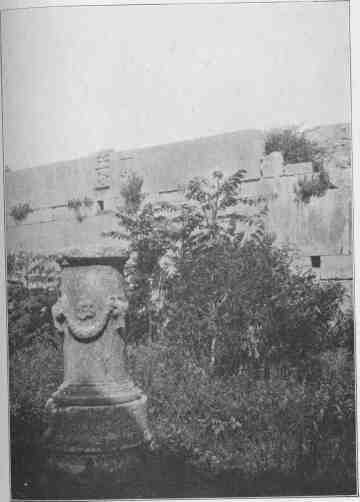

ROMAN ALTAR

40

NORMAN CAPITAL AT

VENOSA 42

SOLE RELIC OF OLD

TARAS 66

FISHING AT TARANTO

68

BY THE INLAND SEA

78

FOUNTAINS OF GALAESUS

80

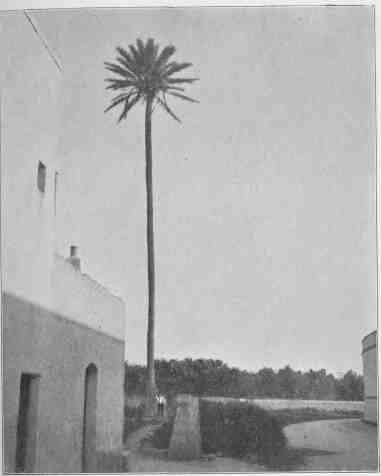

TARANTO : THE LAST

PALM 84

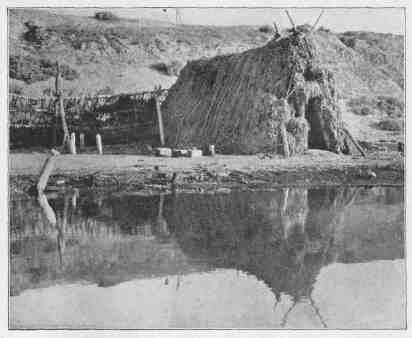

BUFFALO AT POLICORO

98

THE SINNO RIVER

102

CHAPEL OF SAINT MARK

112

SHOEING A COW

120

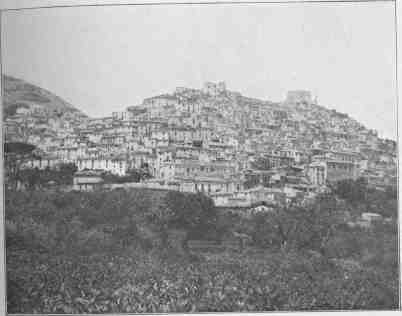

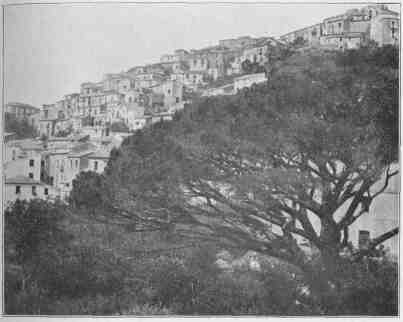

MORANO 130

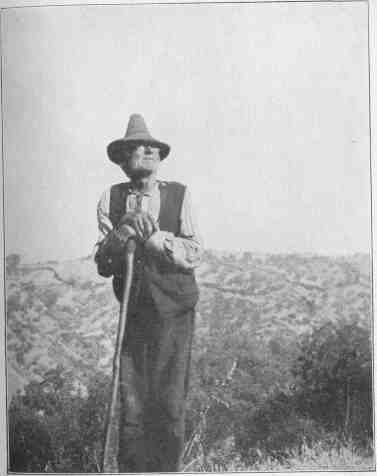

AN OLD SHEPHERD

132

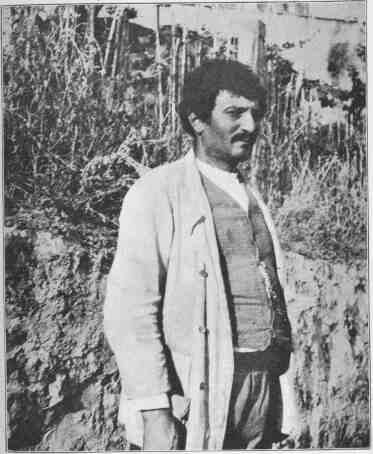

THE SARACENIC TYPE

136

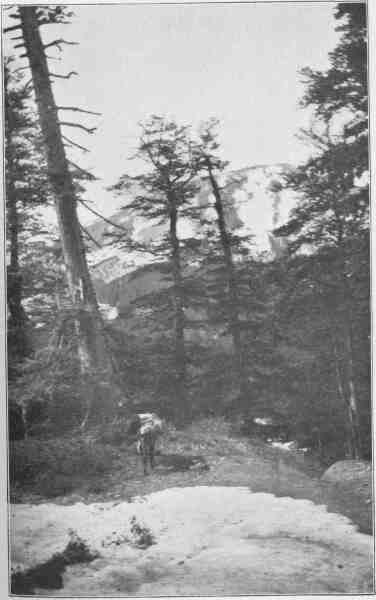

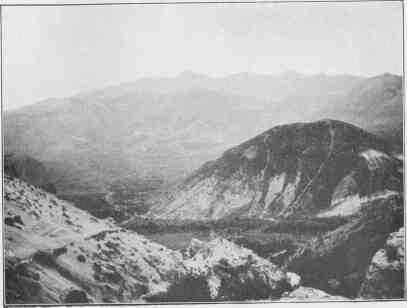

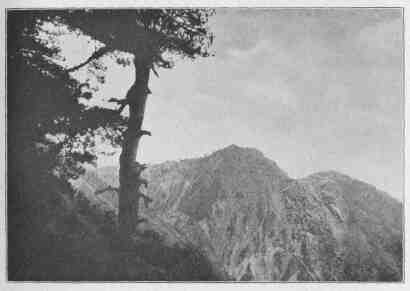

PEAK OF POLLINO IN

JUNE 144

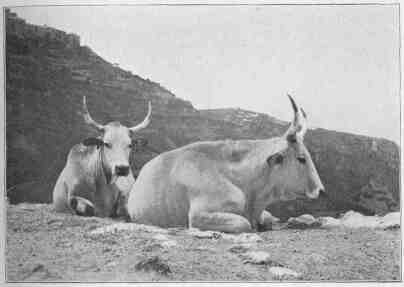

CALABRIAN COWS

148

THE VALLEY OF

GAUDOLINO 156

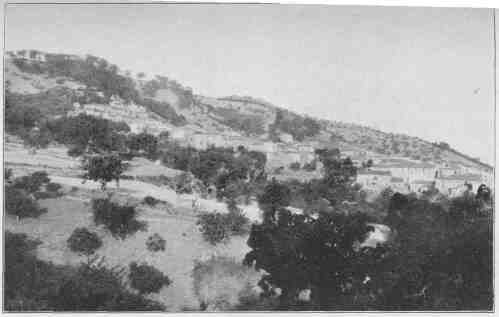

SAN DEMETRIO CORONE

l82

THE TRIONTO VALLEY

198

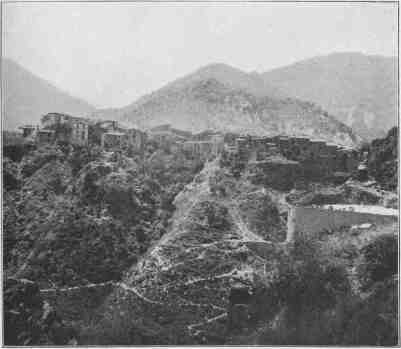

LONGOBUCCO

204

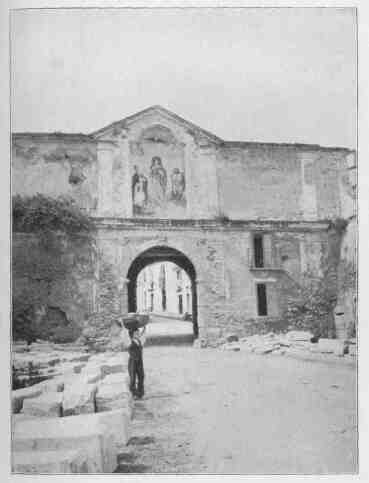

GATEWAY AT CATANZARO

224

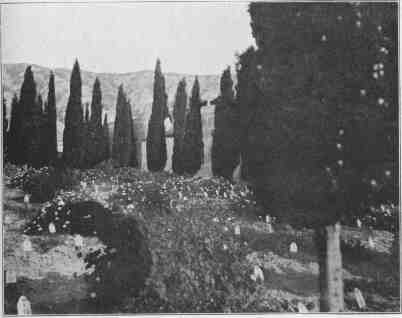

IN THE CEMETERY OF

REGGIO 220

TIRIOLO 228

EFFECTS OF

DEFORESTATION 286

OLD SOVERATO

294

THE MODERN AESARUS

298

CEMETERY OF COTRONE

300

ROMAN MASONRY AT CAPO

COLONNA 32O

OLD

CALABRIA

I

SARACEN LUCERA

I FIND it hard to sum

up in one word the character of Lucera--the effect it produces on

the mind; one sees so many towns that the freshness of their images

becomes blurred. The houses are low but not undignified; the

streets regular and clean; there is electric light and somewhat

indifferent accommodation for travellers; an infinity of barbers

and chemists. Nothing remarkable in all this. Yet the character is

there, if one could but seize upon it, since every place has its

genius. Perhaps it lies in a certain feeling of aloofness that

never leaves one here. We are on a hill--a mere wave of ground; a

kind of spur, rather, rising up from the south--quite an absurd

little hill, but sufficiently high to dominate the wide Apulian

plain. And the nakedness of the land stimulates this aerial sense.

There are some trees in the "Belvedere" or public garden that lies

on the highest part of the spur and affords a fine view north and

eastwards. But the greater part were only planted a few years ago,

and those stretches of brown earth, those half-finished walks and

straggling pigmy shrubs, give the place a crude and embryonic

appearance. One thinks that the designers might have done more in

the way of variety; there are no conifers excepting a few

cryptomerias and yews which will all be dead in a couple of years,

and as for those yuccas, beloved of Italian municipalities, they

will have grown more dyspeptic-looking than ever. None the less,

the garden will be a pleasant spot when the ilex shall have grown

higher; even now it is the favourite evening walk of the citizens.

Altogether, these public parks, which are now being planted all

over south Italy, testify to renascent taste; they and the

burial-places are often the only spots where the deafened and

light-bedazzled stranger may find a little green

2 Old

Calabria

content; the content,

respectively, of L'Allegro and Il Penseroso. So the

cemetery of Lucera, with its ordered walks drowned in the shade of

cypress--roses and gleaming marble monuments in between--is a

charming retreat, not only for the dead.

The Belvedere,

however, is not my promenade. My promenade lies yonder, on the

other side of the valley, where the grave old Suabian castle sits

on its emerald slope. It does not frown; it reposes firmly, with an

air of tranquil and assured domination; "it has found its place,"

as an Italian observed to me. Long before Frederick Barbarossa made

it the centre of his southern dominions, long before the Romans had

their fortress on the site, this eminence must have been regarded

as the key of Apulia. All round the outside of those turreted walls

(they are nearly a mile in circumference; the enclosure, they say,

held sixty thousand people) there runs a level space. This is my

promenade, at all hours of the day. Falcons are fluttering with

wild cries overhead; down below, a long unimpeded vista of velvety

green, flecked by a few trees and sullen streamlets and white

farmhouses--the whole vision framed in a ring of distant Apennines.

The volcanic cone of Mount Vulture, land of Horace, can be detected

on clear days; it tempts me to explore those regions. But eastward

rises up the promontory of Mount Gargano, and on the summit of its

nearest hill one perceives a cheerful building, some village or

convent, that beckons imperiously across the intervening lowlands.

Yonder lies the venerable shrine of the archangel Michael, and

Manfred's town. . . .

This castle being a

national monument, they have appointed a custodian to take

charge of it; a worthless old fellow, full of untruthful

information which he imparts with the hushed and

conscience-stricken air of a man who is selling State

secrets.

"That corner tower,

sir, is the King's tower. It was built by the King."

"But you said just now

that it was the Queen's tower."

"So it is. The

Queen--she built it."

"What

Queen?"

"What Queen? Why, the

Queen--the Queen the German professor was talking about three years

ago. But I must show you some skulls which we found (sotto

voce) in a subterranean crypt. They used to throw the poor dead

folk in here by hundreds; and under the Bourbons the criminals were

hanged here, thousands of them. The blessed times! And this tower

is the Queen's tower."

"But you called it the

King's tower just now."

Saracen Lucera

3

"Just so. That is because

the King built it."

"What King?"

"Ah, sir, how can I

remember the names of all those gentlemen? I haven't so much as set

eyes on them! But I must now show you some round sling-stones which

we excavated (sotto voce) in a subterranean

crypt----"

One or two relics from

this castle are preserved in the small municipal museum, founded

about five years ago. Here are also a respectable collection of

coins, a few prehistoric flints from Gargano, some quaint early

bronze figurines and mutilated busts of Roman celebrities carved in

marble or the recalcitrant local limestone. A dignified old

lion--one of a pair (the other was stolen) that adorned the tomb of

Aurelius, prastor of the Roman Colony of Luceria--has sought a

refuge here, as well as many inscriptions, lamps, vases, and a

miscellaneous collection of modern rubbish. A plaster cast of a

Mussulman funereal stone, found near Foggia, will attract your eye;

contrasted with the fulsome epitaphs of contemporary Christianity,

it breathes a spirit of noble resignation:--

"In the name of Allah,

the Merciful, the Compassionate. May God show kindness to Mahomet

and his kinsfolk, fostering them by his favours! This is the tomb

of the captain Jacchia Albosasso. God be merciful to him. He passed

away towards noon on Saturday in the five days of the month

Moharram of the year 745 (5th April, 1348). May Allah likewise show

mercy to him who reads."

One cannot be at

Lucera without thinking of that colony of twenty thousand Saracens,

the escort of Frederick and his son, who lived here for nearly

eighty years, and sheltered Manfred in his hour of danger. The

chronicler Spinelli* has preserved an anecdote which shows

Manfred's infatuation for these loyal aliens. In the year 1252 and

in the sovereign's presence, a Saracen official gave a blow to a

Neapolitan knight--a blow which was immediately returned; there was

a tumult, and the upshot of it was that the Italian was condemned

to lose his hand; all that the Neapolitan nobles could obtain from

Manfred was that his left hand should be amputated instead of his

right; the Arab, the cause of all, was merely relieved of his

office. Nowadays, all

* These journals are

now admitted to have been manufactured in the sixteenth century by

the historian Costanze for certain genealogical purposes of his

own. Professor Bernhard doubted their authenticity in 1869, and

his doubts have been confirmed by Capasse.

4 Old

Calabria

memory of Saracens has

been swept out of the land. In default of anything better, they are

printing a local halfpenny paper called "II Saraceno"--a very

innocuous pagan, to judge by a copy which I bought in a reckless

moment.

This museum also

contains a buxom angel of stucco known as the "Genius of

Bourbonism." In the good old days it used to ornament the town

hall, fronting the entrance; but now, degraded to a museum

curiosity, it presents to the public its back of ample proportions,

and the curator intimated that he considered this attitude quite

appropriate--historically speaking, of course. Furthermore, they

have carted hither, from the Chamber of Deputies in Rome, the chair

once occupied by Ruggiero Bonghi. Dear Bonghi! From a sense of duty

he used to visit a certain dull and pompous house in the capital

and forthwith fall asleep on the nearest sofa; he slept sometimes

for two hours at a stretch, while all the other visitors were

solemnly marched to the spot to observe him--behold the great

Bonghi: he slumbers! There is a statue erected to him here, and a

street has likewise been named after another celebrity, Giovanni

Bovio. If I informed the townsmen of my former acquaintance with

these two heroes, they would perhaps put up a marble tablet

commemorating the fact. For the place is infected with the

patriotic disease of monumentomania. The drawback is that with

every change of administration the streets are re-baptized and the

statues shifted to make room for new favourites; so the civic

landmarks come and go, with the swiftness of a

cinematograph.

Frederick II also has

his street, and so has Pietjo Giannone. This smacks of

anti-clericalism. But to judge by the number of priests and the

daily hordes of devout and dirty pilgrims that pour into the town

from the fanatical fastnesses of the Abruzzi--picturesque, I

suppose we should call them--the country is sufficiently orthodox.

Every self-respecting family, they tell me, has its pet priest, who

lives on them in return for spiritual consolations.

There was a religious

festival some nights ago in honour of Saint Espedito. No one could

tell me more about this holy man than that he was a kind of

pilgrim-warrior, and that his cult here is of recent date; it was

imported or manufactured some four years ago by a rich merchant

who, tired of the old local saints, built a church in honour of

this new one, and thereby enrolled him among the city

gods.

On this occasion the

square was seething with people: few

Lion of Lucera

Saracen Lucera

5

women, and the men

mostly in dark clothes; we are already under Moorish and Spanish

influences. A young boy addressed me with the polite question

whether I could tell him the precise number of the population of

London.

That depended, I said,

on what one described as London. There was what they called greater

London----

It depended! That was

what he had always been given to understand. . . . And how did I

like Lucera? Rather a dull little place, was it not? Nothing like

Paris, of course. Still, if I could delay my departure for some

days longer, they would have the trial of a man who had murdered

three people: it might be quite good fun. He was informed that they

hanged such persons in England, as they used to do hereabouts; it

seemed rather barbaric, because, naturally, nobody is ever

responsible for his actions; but in England, no

doubt----

That is the normal

attitude of these folks towards us and our institutions. We are

savages, hopeless savages; but a little savagery, after all, is

quite endurable. Everything is endurable if you have lots of money,

like these English.

As for myself,

wandering among that crowd of unshaven creatures, that rustic

population, fiercely gesticulating and dressed in slovenly hats and

garments, I realized once again what the average Anglo-Saxon would

ask himself: Are they all brigands, or only some of them?

That music, too--what is it that makes this stuff so utterly

unpalatable to a civilized northerner? A soulless cult of rhythm,

and then, when the simplest of melodies emerges, they cling to it

with the passionate delight of a child who has discovered the moon.

These men are still in the age of platitudes, so far as music is

concerned; an infantile aria is to them what some foolish rhymed

proverb is to the Arabs: a thing of God, a portent, a joy for

ever.

You may visit the

cathedral; there is a fine verde antico column on either

side of the sumptuous main portal. I am weary, just now, of these

structures; the spirit of pagan Lucera--"Lucera dei Pagani" it

used to be called--has descended upon me; I feel inclined to echo

Carducci's "Addio, nume semitico!" One sees so many of

these sombre churches, and they are all alike in their stony

elaboration of mysticism and wrong-headedness; besides, they have

been described, over and over again, by enthusiastic connaisseurs

who dwell lovingly upon their artistic quaintnesses but forget the

grovelling herd that reared them, with the lash at their backs, or

the odd type of humanity--the gargoyle type--that has since grown

up under their shadow and

6 Old

Calabria

influence. I prefer to

return to the sun and stars, to my promenade

beside the castle

walls.

But for the absence of

trees and hedges, one might take this to be some English prospect

of the drowsy Midland counties--so green it is, so golden-grey the

sky. The sunlight peers down dispersedly through windows in this

firmament of clouded amber, alighting on some mouldering tower,

some patch of ripening corn or distant city--Troia, lapped in

Byzantine slumber, or San Severo famed in war. This in spring. But

what days of glistering summer heat, when the earth is burnt to

cinders under a heavenly dome that glows like a brazier of molten

copper! For this country is the Sahara of Italy.

One is glad,

meanwhile, that the castle does not lie in the natal land of the

Hohenstaufen. The interior is quite deserted, to be sure; they have

built half the town of Lucera with its stones, even as Frederick

quarried them out of the early Roman citadel beneath; but it is at

least a harmonious desolation. There are no wire-fenced walks among

the ruins, no feeding-booths and cheap reconstructions of

draw-bridges and police-notices at every corner; no gaudy women

scribbling to their friends in the "Residenzstadt" post cards

illustrative of the "Burgruine," while their husbands perspire over

mastodontic beer-jugs. There is only peace.

These are the delights

of Lucera: to sit under those old walls and watch the gracious

cloud-shadows dappling the plain, oblivious of yonder assemblage of

barbers and politicians. As for those who can reconstruct the

vanished glories of such a place--happy they! I find the task

increasingly difficult. One outgrows the youthful age of

hero-worship; next, our really keen edges are so soon worn off by

mundane trivialities and vexations that one is glad to take refuge

in simpler pleasures once more--to return to primitive

emotionalism. There are so many Emperors of past days! And like the

old custodian, I have not so much as set eyes on them.

Yet this Frederick is

no dim figure; he looms grandly through the intervening haze. How

well one understands that craving for the East, nowadays; how

modern they were, he and his son the "Sultan of Lucera," and their

friends and counsellors, who planted this garden of exotic culture!

Was it some afterglow of the luminous world that had sunk below the

horizon, or a pale streak of the coming dawn? And if you now glance

down into this enclosure that once echoed with the song of

minstrels

Saracen Lucera

7

and the soft laughter

of women, with the discourse of wits, artists and philosophers, and

the clang of arms--if you look, you will behold nothing but a green

lake, a waving field of grass. No matter. The ambitions of these

men are fairly realized, and every one of us may keep a body-guard

of pagans, an't please him; and a harem likewise--to judge by the

newspapers.

For he took his

Orientalism seriously; he had a harem, with eunuchs, etc., all

proper, and was pleased to give an Eastern colour to his

entertainments. Matthew Paris relates how Frederick's

brother-in-law, returning from the Holy Land, rested awhile at his

Italian court, and saw, among other diversions, "duas puellas

Saracenicas formosas, quae in pavimenti planitie binis globis

insisterent, volutisque globis huo illucque ferrentur canentes,

cymbala manibus collidentes, corporaque secundum modules motantes

atque flectentes." I wish I had been there. . . .

I walked to the castle

yesterday evening on the chance of seeing an eclipse of the moon

which never came, having taken place at quite another hour. A

cloudless night, dripping with moisture, the electric lights of

distant Foggia gleaming in the plain. There are brick-kilns at the

foot of the incline, and from some pools in the neighbourhood

issued a loud croaking of frogs, while the pallid smoke of the

furnaces, pressed down by the evening dew, trailed earthward in a

long twisted wreath, like a dragon crawling sulkily to his den. But

on the north side one could hear the nightingales singing in the

gardens below. The dark mass of Mount Gargano rose up clearly in

the moonlight, and I began to sketch out some itinerary of my

wanderings on that soil. There was Sant' Angelo, the archangel's

abode; and the forest region; and Lesina with its lake; and Vieste

the remote, the end of all things. . . .

Then my thoughts

wandered to the Hohenstaufen and the conspiracy whereby their fate

was avenged. The romantic figures of Manfred and Conradin; their

relentless enemy Charles; Costanza, her brow crowned with a poetic

nimbus (that melted, towards the end, into an aureole of bigotry);

Frangipani, huge in villainy; the princess Beatrix, tottering from

the dungeon where she had been confined for nearly twenty years;

her deliverer Roger de Lauria, without whose resourcefulness and

audacity it might have gone ill with Aragon; Popes and

Palaso-logus--brilliant colour effects; the king of England and

Saint Louis of France; in the background, dimly discernible, the

colossal shades of Frederick and Innocent, looked in deadly

embrace; and the whole congress of figures enlivened and

inter-

8 Old

Calabria

penetrated as by some

electric fluid--the personality of John of Procida. That the

element of farce might not be lacking, Fate contrived that

exquisite royal duel at Bordeaux where the two mighty potentates,

calling each other by a variety of unkingly epithets, enacted a

prodigiously fine piece of foolery for the delectation of

Europe.

From this terrace one

can overlook both Foggia and Castel Fiorentino--the beginning and

end of the drama; and one follows the march of this magnificent

retribution without a shred of compassion for the gloomy papal

hireling. Disaster follows disaster with mathematical precision,

till at last he perishes miserably, consumed by rage and despair.

Then our satisfaction is complete.

No; not quite

complete. For in one point the stupendous plot seems to have been

imperfectly achieved. Why did Roger de Lauria not profit by his

victory to insist upon the restitution of the young brothers of

Beatrix, of those unhappy princes who had been confined as infants

in 1266, and whose very existence seems to have faded from the

memory of historians? Or why did Costanza, who might have dealt

with her enemy's son even as Conradin had been dealt with, not

round her magnanimity by claiming her own flesh and blood, the last

scions of a great house? Why were they not released during the

subsequent peace, or at least in 1302? The reason is as plain as it

is unlovely; nobody knew what to do with them. Political reasons

counselled their effacement, their non-existence. Horrible thought,

that the sunny world should be too small for three orphan children!

In their Apulian fastness they remained--in chains. A royal

rescript of 1295 orders that they be freed from their fetters.

Thirty years in fetters! Their fate is unknown; the night of

medievalism closes in upon them once more. . . .

Further musings were

interrupted by the appearance of a shape which approached from

round the corner of one of the towers. It cams nearer stealthily,

pausing every now and then. Had I evoked, willy-nilly, some phantom

of the buried past?

It was only the

custodian, leading his dog Musolino. After a shower of compliments

and apologies, he gave me to understand that it was his duty, among

other things, to see that no one should endeavour to raise the

treasure which was hidden under these ruins; several people, he

explained, had already made the attempt by night. For the rest, I

was quite at liberty to take my pleisure about the castle at all

hours. But as to touching the buried hoard, it was

proibito--forbidden!

Saracen Lucera

9

I was glad of the

incident, which conjured up for me the Oriental mood with its genii

and subterranean wealth. Straightway this incongruous and

irresponsible old buffoon was invested with a new dignity;

transformed into a threatening Ifrit, the guardian of the gold,

or--who knows?--Iblis incarnate. The gods take wondrous shapes,

sometimes.

II

MANFRED'S TOWN

A the train moved from

Lucera to Foggia and thence onwards, I had enjoyed myself

rationally, gazing at the emerald plain of Apulia, soon to be

scorched to ashes, but now richly dight with the yellow flowers of

the giant fennel, with patches of ruby-red poppy and asphodels pale

and shadowy, past their prime. I had thought upon the history of

this immense tract of country--upon all the floods of legislation

and theorizings to which its immemorial customs of pasturage have

given birth. . . .

Then, suddenly, the

aspect of life seemed to change. I felt unwell, and so swift was

the transition from health that I had wantonly thrown out of the

window, beyond recall, a burning cigar ere realizing that it was

only a little more than half smoked. We were crossing the

Calendaro, a sluggish stream which carefully collects all the

waters of this region only to lose them again in a swamp not far

distant; and it was positively as if some impish sprite had leapt

out of those noisome waves, boarded the train, and flung himself

into me, after the fashion of the "Horla" in the immortal

tale.

Doses of quinine such

as would make an English doctor raise his eyebrows have hitherto

only succeeded in provoking the Calendaro microbe to more virulent

activity. Nevertheless, on s'y fait. I am studying him and,

despite his protean manifestations, have discovered three principal

ingredients: malaria, bronchitis and hay-fever--not your ordinary

hay-fever, oh, no! but such as a mammoth might conceivably catch,

if thrust back from his germless, frozen tundras into the damply

blossoming Miocene.

The landlady of this

establishment has a more commonplace name for the distemper. She

calls it "scirocco." And certainly this pest of the south blows

incessantly; the mountain-line of Gargano is veiled, the sea's

horizon veiled, the coast-lands of Apulia veiled by its tepid and

unwholesome breath. To cheer

Manfred's Town

11

me up, she says that

on clear days one can see Castel del Monte, the Hohenstaufen eyrie,

shining yonder above Barletta, forty miles distant. It sounds

rather improbable; still, yesterday evening there arose a sudden

vision of a white town in that direction, remote and dream-like,

far across the water. Was it Barletta? Or Margherita? It lingered

awhile, poised on an errant sunbeam; then sank into the

deep.

From this window I

look into the little harbour whose beach is dotted with

fishing-boats. Some twenty or thirty sailing-vessels are riding at

anchor; in the early morning they unfurl their canvas and sally

forth, in amicable couples, to scour the azure deep--it is

greenish-yellow at this moment--returning at nightfall with the

spoils of ocean, mostly young sharks, to judge by the display in

the market. Their white sails bear fabulous devices in golden

colour of moons and crescents and dolphins; some are marked like

the "orange-tip" butterfly. A gunboat is now stationed here on a

mysterious errand connected with the Albanian rising on the other

side of the Adriatic. There has been whispered talk of illicit

volunteering among the youth on this side, which the government is

anxious to prevent. And to enliven the scene, a steamer calls every

now and then to take passengers to the Tremiti islands. One would

like to visit them, if only in memory of those martyrs of

Bourbonism, who were sent in hundreds to these rocks and cast into

dungeons to perish. I have seen such places; they are vast caverns

artificially excavated below the surface of the earth; into these

the unfortunates were lowered and left to crawl about and rot, the

living mingled with the dead. To this day they find mouldering

skeletons, loaded with heavy iron chains and

ball-weights.

A copious spring

gushes up on this beach and flows into the sea. It is sadly

neglected. Were I tyrant of Manfredonia, I would build me a fair

marble fountain here, with a carven assemblage of nymphs and

sea-monsters spouting water from their lusty throats, and plashing

in its rivulets. It may well be that the existence of this fount

helped to decide Manfred in his choice of a site for his city; such

springs are rare in this waterless land. And from this same source,

very likely, is derived the local legend of Saint Lorenzo and the

Dragon, which is quite independent of that of Saint Michael the

dragon-killer on the heights above us. These venerable

water-spirits, these dracs, are interesting beasts who went

through many metamorphoses ere attaining their present

shape.

Manfredonia lies on a

plain sloping very gently seawards--

12 Old

Calabria

practically a dead

level, and in one of the hottest districts of Italy. Yet, for some

obscure reason, there is no street along the sea itself; the

cross-roads end in abrupt squalor at the shore. One wonders what

considerations--political, aesthetic or hygienic--prevented the

designers of the town from carrying out its general principles of

construction and building a decent promenade by the waves, where

the ten thousand citizens could take the air in the breathless

summer evenings, instead of being cooped up, as they now are,

within stifling hot walls. The choice of Manfredonia as a port

does not testify to any great foresight on the part of its

founder--peace to his shade! It will for ever slumber in its bay,

while commerce passes beyond its reach; it will for ever be

malarious with the marshes of Sipontum at its edges. But this

particular defect of the place is not Manfred's fault, since the

city was razed to the ground by the Turks in 1620, and then built

up anew; built up, says Lenormant, according to the design of the

old city. Perhaps a fear of other Corsair raids induced the

constructors to adhere to the old plan, by which the place could be

more easily defended. Not much of Manfredonia seems to have been

completed when Pacicchelli's view (1703) was engraved.

Speaking of the

weather, the landlady further told me that the wind blew so hard

three months ago--"during that big storm in the winter, don't you

remember?"--that it broke all the iron lamp-posts between the town

and the station. Now here was a statement sounding even more

improbable than her other one about Castel del Monte, but admitting

of verification. Wheezing and sneezing, I crawled forth, and found

it correct. It must have been a respectable gale, since the

cast-iron supports are snapped in half, every one of

them.

Those Turks, by the

way, burnt the town on that memorable occasion. That was a common

occurrence in those days. Read any account of their incursions into

Italy during this and the preceding centuries, and you will find

that the corsairs burnt the towns whenever they had time to set

them alight. They could not burn them nowadays, and this points to

a total change in economic conditions. Wood was cut down so

heedlessly that it became too scarce for building purposes, and

stone took its place. This has altered domestic architecture; it

has changed the landscape, denuding the hill-sides that were once

covered with timber; it has impoverished the country by converting

fruitful plains into marshes or arid tracts of stone swept by

irregular and intermittent floods; it has modified, if I

mistake

Manfredi Town

13

not, the very

character of the people. The desiccation of the climate has

entailed a desiccation of national humour.

Muratori has a passage

somewhere in his "Antiquities" regarding the old method of

construction and the wooden shingles, scandulae, in use for

roofing--I must look it up, if ever I reach civilized regions

again.

At the municipality,

which occupies the spacious apartments of a former Dominican

convent, they will show you the picture of a young girl, one of the

Beccarmi family, who was carried off at a tender age in one of

these Turkish raids, and subsequently became "Sultana." Such

captive girls generally married sultans--or ought to have married

them; the wish being father to the thought. But the story is

disputed; rightly, I think. For the portrait is painted in the

French manner, and it is hardly likely that a harem-lady would have

been exhibited to a European artist. The legend goes on to say that

she was afterwards liberated by the Knights of Malta, together with

her Turkish son who, as was meet and proper, became converted to

Christianity and died a monk. The Beccarmi family (of Siena, I

fancy) might find some traces of her in their archives. Ben

trovato, at all events. When one looks at the pretty portrait,

one cannot blame any kind of "Sultan" for feeling well-disposed

towards the original.

The weather has shown

some signs of improvement and tempted me, despite the persistent

"scirocco" mood, to a few excursions into the neighbourhood. But

there seem to be no walks hereabouts, and the hills, three miles

distant, are too remote for my reduced vitality. The intervening

region is a plain of rock carved so smoothly, in places, as to

appear artificially levelled with the chisel; large tracts of it

are covered with the Indian fig (cactus). In the shade of these

grotesque growths lives a dainty flora: trembling grasses of many

kinds, rue, asphodel, thyme, the wild asparagus, a diminutive blue

iris, as well as patches of saxifrage that deck the stone with a

brilliant enamel of red and yellow. This wild beauty makes one

think how much better the graceful wrought-iron balconies of the

town would look if enlivened with blossoms, with pendent carnations

or pelargonium; but there is no great display of these things; the

deficiency of water is a characteristic of the place; it is a

flowerless and songless city. The only good drinking-water is that

which is bottled at the mineral springs of Monte Vulture and sold

cheaply enough all over the country. And the mass of the country

people have small charm of feature. Their faces seem to have been

chopped

14 Old

Calabria

with a hatchet into

masks of sombre virility; a hard life amid burning limestone

deserts is reflected in their countenances.

None the less, they

have a public garden; even more immature than that of Lucera, but

testifying to greater taste. Its situation, covering a forlorn

semicircular tract of ground about the old Anjou castle, is a

priori a good one. But when the trees are fully grown, it will

be impossible to see this fine ruin save at quite close

quarters--just across the moat.

I lamented this fact

to a solitary gentleman who was strolling about here and who

replied, upon due deliberation:

"One cannot have

everything."

Then he added, as a

suggestive afterthought:

"Inasmuch as one thing

sometimes excludes another."

I pause, to observe

parenthetically that this habit of uttering platitudes in the grand

manner as though disclosing an idea of vital novelty (which Charles

Lamb, poor fellow, thought peculiar to natives of Scotland) is as

common among Italians as among Englishmen. But veiled in sonorous

Latinisms, the staleness of such remarks assumes an air of

profundity.

"For my part," he went

on, warming to his theme, "I am thoroughly satisfied. Who will

complain of the trees? Only a few makers of bad pictures. They can

go elsewhere. Our country, dear sir, is encrusted, with old

castles and other feudal absurdities, and if I had the management

of things----"

The sentence was not

concluded, for at that moment his hat was blown off by a violent

gust of wind, and flew merrily over beds of flowering marguerites

in the direction of the main street, while he raced after it,

vanishing in a cloud of dust. The chase must have been long and

arduous; he never returned.

Wandering about the

upper regions of this fortress whose chambers are now used as a

factory of cement goods and a refuge for some poor families, I

espied a good pre-renaissance relief of Saint Michael and the

dragon immured in the masonry, and overhung by the green leaves of

an exuberant wild fig that has thrust its roots into the sturdy old

walls. Here, at Manfredonia, we are already under the shadow of the

holy mountain and the archangel's wings, but the usual

representations of him are childishly emasculate--the negation of

his divine and heroic character. This one portrays a genuine

warrior-angel of the old type: grave and grim. Beyond this castle

and the town-walls, which are best preserved on the north side,

nothing in Manfredonia is older than 1620. There is a fine

campanile, but the cathedral looks like a shed for disused

omnibuses.

Manfredi Town I

5

Along the streets,

little red flags are hanging out of the houses, at frequent

intervals: signals of harbourage for the parched wayfarer. Within,

you behold a picturesque confusion of rude chairs set among barrels

and vats full of dark red wine where, amid Rembrandtesque

surroundings, you can get as drunk as a lord for sixpence. Blithe

oases! It must be delightful, in summer, to while away the sultry

hours in their hospitable twilight; even at this season they seem

to be extremely popular resorts, throwing a new light on those

allusions by classical authors to "thirsty Apulia."

But on many of the

dwellings I noticed another symbol: an ominous blue metal tablet

with a red cross, bearing the white-lettered words "VIGILANZA

NOTTURNA."

Was it some

anti-burglary association? I enquired of a serious-looking

individual who happened to be passing.

His answer did not

help to clear up matters.

"A pure job, signore

mio, a pure job! There is a society in Cerignola or

somewhere, a society which persuades the various town

councils--persuades them, you understand----"

He ended abruptly,

with the gesture of paying out money between his finger and thumb.

Then he sadly shook his head.

I sought for more

light on this cryptic utterance; in vain. What were the facts, I

persisted? Did certain householders subscribe to keep a guardian on

their premises at night--what had the municipalities to do with

it--was there much house-breaking in Manfredonia, and, if so, had

this association done anything to check it? And for how long had

the institution been established?

But the mystery grew

ever darker. After heaving a deep sigh, he condescended to

remark:

"The usual camorra!

Eat--eat; from father to son. Eat--eat! That's all they think

about, the brood of assassins. . . . Just look at them!"

I glanced down the

street and beheld a venerable gentleman of kindly aspect who

approached slowly, leaning on the arm of a fair-haired youth--his

grandson, I supposed. He wore a long white beard, and an air of

apostolic detachment from the affairs of this world. They came

nearer. The boy was listening, deferentially, to some remark of the

elder; his lips were parted in attention and his candid, sunny face

would have rejoiced the heart of della Robbia. They passed within a

few feet of me, lovingly engrossed in one another.

16 Old

Calabria

"Well?" I queried,

turning to my informant and anxious to learn what misdeeds could be

laid to the charge of such godlike types of humanity.

But that person was no

longer at my side. He had quietly withdrawn himself, in the

interval; he had evanesced, "moved on."

An oracular and

elusive citizen. ...

III

THE ANGEL OF

MANFREDONIA

WHOEVER looks at a map

of the Gargano promontory will see that it is besprinkled with

Greek names of persons and places--Matthew, Mark, Nikander,

Onofrius, Pirgiano (Pyrgos) and so forth. Small wonder, for these

eastern regions were in touch with Constantinople from early days,

and the spirit of Byzance still hovers over them. It was on this

mountain that the archangel Michael, during his first flight to

Western Europe, deigned to appear to a Greek bishop of Sipontum,

Laurentius by name; and ever since that time a certain cavern,

sanctified by the presence of this winged messenger of God, has

been the goal of millions of pilgrims.

The fastness of Sant'

Angelo, metropolis of European angel-worship, has grown up around

this "devout and honourable cave"; on sunny days its houses are

clearly visible from Manfredonia. They who wish to pay their

devotions at the shrine cannot do better than take with them

Gregorovius, as cicerone and mystagogue.

Vainly I waited for a

fine day to ascend the heights. At last I determined to have done

with the trip, be the weather what it might. A coachman was

summoned and negotiations entered upon for starting next

morning.

Sixty-five francs, he

began by telling me, was the price paid by an Englishman last year

for a day's visit to the sacred mountain. It may well be

true--foreigners will do anything, in Italy. Or perhaps it was only

said to "encourage" me. But I am rather hard to encourage,

nowadays. I reminded the man that there was a diligence service

there and back for a franc and a half, and even that price seemed

rather extortionate. I had seen so many holy grottos in my life!

And who, after all, was this Saint Michael? The Eternal Father,

perchance? Nothing of the kind: just an ordinary angel! We had

dozens of them, in England. Fortunately, I added, I had already

received an offer to join one of the private parties who drive up,

fourteen or fifteen persons behind c 17

18 Old

Calabria

one diminutive

pony--and that, as he well knew, would be a matter of only a few

pence. And even then, the threatening sky . . . Yes, on second

thoughts, it was perhaps wisest to postpone the excursion

altogether. Another day, if God wills! Would he accept this cigar

as a recompense for his trouble in coming?

In dizzy leaps and

bounds his claims fell to eight francs. It was the tobacco that

worked the wonder; a gentleman who will give something for

nothing (such was his logic)--well, you never know what you may

not get out of him. Agree to his price, and chance it!

He consigned the cigar

to his waistcoat pocket to smoke after dinner, and

departed--vanquished, but inwardly beaming with bright

anticipation.

A wretched morning was

disclosed as I drew open the shutters--gusts of rain and sleet

beating against the window-panes. No matter: the carriage stood

below, and after that customary and hateful apology for breakfast

which suffices to turn the thoughts of the sanest man towards

themes of suicide and murder--when will southerners learn to eat a

proper breakfast at proper hours?--we started on our journey. The

sun came out in visions of tantalizing briefness, only to be

swallowed up again in driving murk, and of the route we traversed I

noticed only the old stony track that cuts across the twenty-one

windings of the new carriage-road here and there. I tried to

picture to myself the Norman princes, the emperors, popes, and

other ten thousand pilgrims of celebrity crawling up these rocky

slopes--barefoot--on such a day as this. It must have tried the

patience even of Saint Francis of Assisi, who pilgrimaged with the

rest of them and, according to Pontanus, performed a little miracle

here en passant, as was his wont.

After about three

hours' driving we reached the town of Sant' Angelo. It was bitterly

cold at this elevation of 800 metres. Acting on the advice of the

coachman, I at once descended into the sanctuary; it would be warm

down there, he thought. The great festival of 8 May was over, but

flocks of worshippers were still arriving, and picturesquely pagan

they looked in grimy, tattered garments--their staves tipped with

pine-branches and a scrip.

In the massive bronze

doors of the chapel, that were made at Constantinople in 1076 for a

rich citizen of Amalfi, metal rings are inserted; these, like a

true pilgrim, you must clash furiously, to call the attention of

the Powers within to your visit; and on issuing, you must once more

knock as hard as you can, in order

The Angel of

Manfredonia 19

that the consummation

of your act of worship may be duly reported: judging by the noise

made, the deity must be very hard of hearing. Strangely deaf they

are, sometimes.

The twenty-four panels

of these doors are naively encrusted with representations, in

enamel, of angel-apparitions of many kinds; some of them are

inscribed, and the following is worthy of note:

"I beg and implore the

priests of Saint Michael to cleanse these gates once a year as I

have now shown them, in order that they may be always bright and

shining." The recommendation has plainly not been carried out for a

good many years past.

Having entered the

portal, you climb down a long stairway amid swarms of pious, foul

clustering beggars to a vast cavern, the archangel's abode. It is a

natural recess in the rock, illuminated by candles. Here divine

service is proceeding to the accompaniment of cheerful operatic

airs from an asthmatic organ; the water drops ceaselessly from the

rocky vault on to the devout heads of kneeling worshippers that

cover the floor, lighted candle in hand, rocking themselves

ecstatically and droning and chanting. A weird scene, in truth. And

the coachman was quite right in his surmise as to the difference in

temperature. It is hot down here, damply hot, as in an

orchid-house. But the aroma cannot be described as a floral

emanation: it is the bouquet, rather, of thirteen centuries

of unwashed and perspiring pilgrims. "TERRIBILIS EST LOCUS ISTE,"

says an inscription over the entrance of the shrine. Very true. In

places like this one understands the uses, and possibly the origin,

of incense.

I lingered none the

less, and my thoughts went back to the East, whence these

mysterious practices are derived. But an Oriental crowd of

worshippers does not move me like these European masses of

fanaticism; I can never bring myself to regard without a certain

amount of disquietude such passionate pilgrims. Give them their new

Messiah, and all our painfully accumulated art and knowledge, all

that reconciles civilized man to earthly existence, is blown to the

winds. Society can deal with its criminals. Not they, but fond

enthusiasts such as these, are the menace to its stability. Bitter

reflections; but then--the drive upward had chilled my human

sympathies, and besides--that so-called breakfast. . . .

The grovelling herd

was left behind. I ascended the stairs and, profiting by a gleam of

sunshine, climbed up to where, above the town, there stands a proud

aerial ruin known as the "Castle of

20 Old

Calabria

the Giant." On one of

its stones is inscribed the date 1491--a certain Queen of Naples,

they say, was murdered within those now crumbling walls. These

sovereigns were murdered in so many castles that one wonders how

they ever found time to be alive at all. The structure is a wreck

and its gateway closed up; nor did I feel any great inclination, in

that icy blast of wind, to investigate the roofless

interior.

I was able to observe,

however, that this "feudal absurdity" bears a number like any

inhabited house of Sant' Angelo--it is No. 3.

This is the latest

pastime of the Italian Government: to re-number dwellings

throughout the kingdom; and not only human habitations, but walls,

old ruins, stables, churches, as well as an occasional door-post

and window. They are having no end of fun over the game, which

promises to keep them amused for any length of time--in fact, until

the next craze is invented. Meanwhile, so long as the fit lasts,

half a million bright-eyed officials, burning with youthful ardour,

are employed in affixing these numerals, briskly entering them into

ten times as many note-books and registering them into thousands of

municipal archives, all over the country, for some inscrutable but

hugely important administrative purposes. "We have the employes,"

as a Roman deputy once told me, "and therefore: they must find some

occupation."

Altogether, the

weather this day sadly impaired my appetite for research and

exploration. On the way to the castle I had occasion to admire the

fine tower and to regret that there seemed to exist no coign of

vantage from which it could fairly be viewed; I was struck, also,

by the number of small figures of Saint Michael of an

ultra-youthful, almost infantile, type; and lastly, by certain

clean-shaven old men of the place. These venerable and decorative

brigands--for such they would have been, a few years ago--now stood

peacefully at their thresholds, wearing a most becoming cloak of

thick brown wool, shaped like a burnous. The garment interested me;

it may be a legacy from the Arabs who dominated this region for

some little time, despoiling the holy sanctuary and leaving their

memory to be perpetuated by the neighbouring "Monte Saraceno." The

costume, on the other hand, may have come over from Greece; it is

figured on Tanagra statuettes and worn by modern Greek shepherds.

By Sardinians, too. ... It may well be a primordial form of

clothing with mankind.

The view from this

castle must be superb on clear days. Standing there, I looked

inland and remembered all the places I had

The Angel of'

Manfredoni a 21

intended to

see--Vieste, and Lesina with its lakes, and Selva Umbra, whose very

name is suggestive of dewy glades; how remote they were, under such

dispiriting clouds! I shall never see them. Spring hesitates to

smile upon these chill uplands; we are still in the grip of

winter--

Aut aquilonibus

Querceti Gargani laborent Et foliis viduantur orni--

so sang old Horace, of

Garganian winds. I scanned the horizon, seeking for his Mount

Vulture, but all that region was enshrouded in a grey curtain of

vapour; only the Stagno Salso--a salt mere wherein Candelaro

forgets his mephitic waters--shone with a steady glow, like a sheet

of polished lead.

Soon the rain fell

once more and drove me to seek refuge among the houses, where I

glimpsed the familiar figure of my coachman, sitting disconsolately

under a porch. He looked up and remarked (for want of something

better to say) that he had been searching for me all over the town,

fearing that some mischief might have happened to me. I was touched

by these words; touched, that is, by his child-like simplicity in

imagining that he could bring me to believe a statement of such

radiant improbability; so touched, that I pressed a franc into his

reluctant palm and bade him buy with it something to eat. A whole

franc. . . . Aha! he doubtless thought, my theory of the

gentleman: it begins to work.

It was barely midday.

Yet I was already surfeited with the angelic metropolis, and my

thoughts began to turn in the direction of Manfredonia once more.

At a corner of the street, however, certain fluent vociferations in

English and Italian, which nothing would induce me to set down

here, assailed my ears, coming up--apparently--out of the bowels of

the earth. I stopped to listen, shocked to hear ribald language in

a holy town like this; then, impelled by curiosity, descended a

long flight of steps and found myself in a subterranean

wine-cellar. There was drinking and card-playing going on here

among a party of emigrants--merry souls; a good half of them spoke

English and, despite certain irreverent phrases, they quickly won

my heart with a "Here! You drink this, mister."

This dim recess was an

instructive pendant to the archangel's cavern. A new type of

pilgrim has been evolved; pilgrims who think no more of crossing to

Pittsburg than of a drive to Manfredonia. But their cave was

permeated with an odour of spilt wine and tobacco-smoke instead of

the subtle Essence des pèlerins

22 Old

Calabria

àes Abruzzes

fleuris, and alas, the object of their worship was not the

Chaldean angel, but another and equally ancient eastern shape:

Mammon. They talked much of dollars; and I also heard several

unorthodox allusions to the "angel-business," which was described

as "played out," as well as a remark to the effect that "only

damn-fools stay in this country." In short, these men were at the

other end of the human scale; they were the strong, the energetic;

the ruthless, perhaps; but certainly--the intelligent.

And all the while the

cup circled round with genial iteration, and it was universally

agreed that, whatever the other drawbacks of Sant' Angelo might be,

there was nothing to be said against its native liquor.

It was, indeed, a

divine product; a vino di montagna of noble pedigree. So I

thought, as I laboriously scrambled up the stairs once more,

solaced by this incident of the competition-grotto and slightly

giddy, from the tobacco-smoke. And here, leaning against the

door-post, stood the coachman who had divined my whereabouts by

some dark masonic intuition of sympathy. His face expanded into an

inept smile, and I quickly saw that instead of fortifying his

constitution with sound food, he had tried alcoholic methods of

defence against the inclement weather. Just a glass of wine, he

explained. "But," he added, "the horse is perfectly

sober."

That quadruped was

equal to the emergency. Gloriously indifferent to our fates, we

glided down, in a vertiginous but masterly vol-plane, from the

somewhat objectionable mountain-town.

An approving burst of

sunshine greeted our arrival on the plain.

IV

CAVE-WORSHIP

WHY has the exalted

archangel chosen for an abode this reeking cell, rather than some

well-built temple in the sunshine? "As symbolizing a ray of light

that penetrates into the gloom," so they will tell you. It is more

likely that he entered it as an extirpating warrior, to oust that

heathen shape which Strabo describes as dwelling in its dank

recesses, and to take possession of the cleft in the name of

Christianity. Sant' Angelo is one of many places where Michael has

performed the duty of Christian Hercules, cleanser of Augean

stables.

For the rest, this

cave-worship is older than any god or devil. It is the cult of the

feminine principle--a relic of that aboriginal obsession of mankind

to shelter in some Cloven Rock of Ages, in the sacred womb of

Mother Earth who gives us food and receives us after death.

Grotto-apparitions, old and new, are but the popular explanations

of this dim primordial craving, and hierophants of all ages have

understood the commercial value of the holy shudder which

penetrates in these caverns to the heart of worshippers, attuning

them to godly deeds. So here, close beside the altar, the priests

are selling fragments of the so-called "Stone of Saint Michael."

The trade is brisk.

The statuette of the

archangel preserved in this subterranean chapel is a work of the

late Renaissance. Though savouring of that mawkish elaboration

which then began to taint local art and literature and is bound up

with the name of the poet Marino, it is still a passably virile

figure. But those countless others, in churches or over

house-doors--do they indeed portray the dragon-killer, the martial

prince of angels? This amiable child with girlish features--can

this be the Lucifer of Christianity, the Sword of the Almighty?

Quis ut Déus! He could hardly hurt a fly.

The hoary winged

genius of Chaldea who has absorbed the essence of so many solemn

deities has now, in extreme old age, entered upon a second

childhood and grown altogether too

23

24 Old

Calabria

youthful for his

role, undergoing a metimorphosis beyond the boundaries of

legendary probability or common sense; every trace of divinity and

manly strength has been boiled out of him. So young and earthly

fair, he looks, rather, like some pretty boy dressed up for a game

with toy sword and helmet--one wants to have a romp with him. No

warrior this! C'est beau, mais ce n'est pas la

guerre.

The gods, they say,

are ever young, and a certain sensuous and fleshly note is

essential to those of Italy if they are to retain the love of their

worshippers. Granted. We do not need a scarred and hirsute veteran;

but we need, at least, a personage capable of wielding the sword, a

figure something like this:--

His starry helm

unbuckled show'd his prime In manhood where youth ended; by his

side As in a glist'ring zodiac hung the sword, Satan's dire dread,

and in his hand the spear. . . .

There! That is an

archangel of the right kind.

And the great dragon,

that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, has suffered a

similar transformation. He is shrunk into a poor little reptile,

the merest worm, hardly worth crushing.

But how should a

sublime conception like the apocalyptic hero appeal to the common

herd? These formidable shapes emerge from the dusk, offspring of

momentous epochs; they stand aloof at first, but presently their

luminous grandeur is dulled, their haughty contour sullied and

obliterated by attrition. They are dragged down to the level of

their lowest adorers, for the whole flock adapts its pace to that

of the weakest lamb. No self-respecting deity will endure this

treatment--to be popularized and made intelligible to a crowd.

Divinity comprehended of the masses ceases to be efficacious; the

Egyptians and Brahmans understood that. It is not giving gods a

chance to interpret them in an incongruous and unsportsmanlike

fashion. But the vulgar have no idea of propriety or fair play;

they cannot keep at the proper distance; they are for ever taking

liberties. And, in the end, the proudest god is forced to

yield.

We see this same

fatality in the very word Cherub. How different an image does this

plump and futile infant evoke to the stately Minister of the Lord,

girt with a sword of flame! We see it in the Italian Madonna of

whom, whatever her mental acquirements may have been, a certain

gravity of demeanour is to be presupposed, and who, none the less,

grows more childishly

Cave- Worship

25

smirking every day; in

her Son who--hereabouts at least--has doffed all the serious

attributes of manhood and dwindled into something not much better

than a doll. It was the same in days of old. Apollo (whom Saint

Michael has supplanted), and Eros, and Aphrodite--they all go

through a process of saccharine deterioration. Our fairest

creatures, once they have passed their meridian vigour, are liable

to be assailed and undermined by an insidious diabetic

tendency.

It is this coddling

instinct of mankind which has reduced Saint Michael to his present

state. And an extraneous influence has worked in the same

direction--the gradual softening of manners within historical

times, that demasculinization which is an inevitable concomitant of

increasing social security. Divinity reflects its human creators

and their environment; grandiose or warlike gods become

superfluous, and finally incomprehensible, in humdrum days of

peace. In order to survive, our deities (like the rest of us) must

have a certain plasticity. If recalcitrant, they are quietly

relieved of their functions, and forgotten. This is what has

happened in Italy to God the Father and the Holy Ghost, who have

vanished from the vulgar Olympus; whereas the devil, thanks to that

unprincipled versatility for which he is famous, remains ever young

and popular.

The art-notions of the

Cinque-Cento are also to blame; indeed, so far as the angelic

shapes of south Italy are concerned, the influence of the

Renaissance has been wholly malefic. Aliens to the soil, they were

at first quite unknown--not one is pictured in the Neapolitan

catacombs. Next came the brief period of their artistic glory; then

the syncretism of the Renaissance, when these winged messengers

were amalgamated with pagan amoretti and began to flutter in

foolish baroque fashion about the Queen of Heaven, after the

pattern of the disreputable little genii attendant upon a Venus of

a bad school. That same instinct which degraded a youthful Eros

into the childish Cupid was the death-stroke to the pristine

dignity and holiness of angels. Nowadays, we see the perversity of

it all; we have come to our senses and can appraise the

much-belauded revival at its true worth; and our modern sculptors

will rear you a respectable angel, a grave adolescent, according to

the best canons of taste--should you still possess the faith that

once requisitioned such works of art.

We travellers acquaint

ourselves with the lineage of this celestial Messenger, but it can

hardly be supposed that the worshippers now swarming at his shrine

know much of these things. How

20 Old

Calabria

shall one discover

their real feelings in regard to this great cave-saint and his life

and deeds?

Well, some idea of

this may be gathered from the literature sold on the spot. I

purchased three of these modern tracts printed respectively at

Bitonto, Molfetta and Naples. The "Popular Song in honour of St.

Michael" contains this verse:

Nell' ora della morte

Ci salvi dal!' inferno E a Regno Sempiterno Ci guidi per

pietà.

Ci guidi per

pietà. . . . This is the Mercury-heritage. Next, the

"History and Miracles of St. Michael" opens with a rollicking

dialogue in verse between the archangel and the devil concerning a

soul; it ends with a goodly list, in twenty-five verses, of the

miracles performed by the angel, such as helping women in

childbirth, curing the blind, and other wonders that differ nothing

from those wrought by humbler earthly saints. Lastly, the "Novena

in Onore di S. Michele Arcangelo," printed in 1910 (third edition)

with ecclesiastical approval, has the following noteworthy

paragraph on the

"DEVOTION FOR THE

SACRED STONES OF THE GROTTO OF ST. MICHAEL.

"It is very salutary

to hold in esteem the STONES which are taken from the sacred

cavern, partly because from immemorial times they have always been

held in veneration by the faithful and also because they have been

placed as relics of sepulchres and altars. Furthermore, it is known

that during the plague which afflicted the kingdom of Naples in the

year 1656, Monsignor G. A. Puccini, archbishop of Manfredonia,

recommended every one to carry devoutly on his person a fragment of

the sacred STONE, whereby the majority were saved from the

pestilence, and this augmented the devotion bestowed on

them."

The cholera is on the

increase, and this may account for the rapid sale of the STONES at

this moment.

This pamphlet also

contains a litany in which the titles of the archangel are

enumerated. He is, among other things, Secretary of God, Liberator

from Infernal Chains, Defender in the Hour of Death, Custodian of

the Pope, Spirit of Light, Wisest of Magistrates, Terror of Demons,

Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the Lord, Lash of Heresies,

Adorer of the Word In-

Cave-Worship 2

7

carnate, Guide of

Pilgrims, Conductor of Mortals: Mars, Mercury, Hercules, Apollo,

Mithra--what nobler ancestry can angel desire? And yet, as if these

complicated and responsible functions did not suffice for his

energies, he has twenty others, among them being that of "Custodian

of the Holy Family "--who apparently need a protector, a Monsieur

Paoli, like any mortal royalties.

"Blasphemous rubbish!

" I can hear some Methodist exclaiming. And one may well be tempted

to sneer at those pilgrims for the more enlightened of whom such

literature is printed. For they are unquestionably a repulsive

crowd: travel-stained old women, under-studies for the Witch of

Endor; dishevelled, anaemic and dazed-looking girls; boys, too weak

to handle a spade at home, pathetically uncouth, with mouths agape

and eyes expressing every grade of uncontrolled emotion--from

wildest joy to downright idiotcy. How one realizes, down in this

cavern, the effect upon some cultured ancient like Rutilius

Namatianus of the catacomb-worship among those early Christian

converts, those men who shun the light, drawn as they were

from the same social classes towards the same dark underground

rites! One can neither love nor respect such people; and to affect

pity for them would be more consonant with their religion than with

my own.

But it is perfectly

easy to understand them. For thirteen centuries this

pilgrim-movement has been going on. Thirteen centuries? No. This

site was an oracle in heathen days, and we know that such were

frequented by men not a whit less barbarous and bigoted than their

modern representatives--nothing is a greater mistake than to

suppose that the crowds of old Rome and Athens were more refined

than our own ("Demosthenes, sir, was talking to an assembly of

brutes"). For thirty centuries then, let us say, a deity has

attracted the faithful to his shrine--Sant' Angelo has become a

vacuum, as it were, which must be periodically filled up from the

surrounding country. These pilgrimages are in the blood of the

people: infants, they are carried there; adults, they carry their

own offspring; grey-beards, their tottering steps are still

supported by kindly and sturdier fellow-wanderers.

Popes and emperors no

longer scramble up these slopes; the spirit of piety has abated

among the great ones of the earth; so much is certain. But the rays

of light that strike the topmost branches have not yet penetrated

to the rank and seething undergrowth. And then--what else can one

offer to these Abruzzi

28 Old

Calabria

mountain-folk? Their

life is one of miserable, revolting destitution. They have no games

or sports, no local racing, clubs, cattle-shows, fox-hunting,

politics, rat-catching, or any of those other joys that diversify

the lives of our peasantry. No touch of humanity reaches them, no

kindly dames send them jellies or blankets, no cheery doctor

enquires for their children; they read no newspapers or books, and

lack even the mild excitements of church versus chapel, or

the vicar's daughter's love-affair, or the squire's latest row with

his lady--nothing! Their existence is almost bestial in its

blankness. I know them--I have lived among them. For four months in

the year they are cooped up in damp dens, not to be called

chambers, where an Englishman would deem it infamous to keep a

dog--cooped up amid squalor that must be seen to be believed; for

the rest of the time they struggle, in the sweat of their brow, to

wrest a few blades of corn from the ungrateful limestone. Their

visits to the archangel--these vernal and autumnal picnics--are

their sole form of amusement.

The movement is said

to have diminished since the early nineties, when thirty thousand

of them used to come here annually. It may well be the case; but I

imagine that this is due not so much to increasing enlightenment as

to the depopulation caused by America; many villages have recently

been reduced to half their former number of inhabitants.

And here they kneel,

candle in hand, on the wet flags of this foetid and malodorous

cave, gazing in rapture upon the blandly beaming idol, their

sensibilities tickled by resplendent priests reciting full-mouthed

Latin phrases, while the organ overhead plays wheezy extracts from

"La Forza del Destino" or the Waltz out of Boito's "Mefistofele"...

for sure, it must be a foretaste of Heaven! And likely enough,

these are "the poor in heart" for whom that kingdom is

reserved.

One may call this a

debased form of Christianity. Whether it would have been

distasteful to the feelings of the founder of that cult is another

question, and, debased or not, it is at least alive and

palpitating, which is more than can be said of certain other

varieties. But the archangel, as was inevitable, has suffered a sad

change. His fairest attribute of Light-bringer, of Apollo, is no

longer his own; it has been claimed and appropriated by the "Light

of the World," his new master. One by one, his functions have been

stripped from him, all save in name, as happens to men and angels

alike, when they take service under "jealous" lords.

Cave-Worship

29

What is now left of

Saint Michael, the glittering hierarch? Can he still endure the

light of sun? Or has he not shrivelled into a spectral Hermes, a

grisly psychopomp, bowing his head in minished glory, and leading

men's souls no longer aloft but downwards--down to the pale regions

of things that have been? And will it be long ere he, too, is

thrust by some flaming Demogorgon into these same realms of Minos,

into that shadowy underworld where dwell Saturn, and Kronos, and

other cracked and shivered ideals?

So I mused that

afternoon, driving down the slopes from Sant' Angelo comfortably

sheltered against the storm, while the generous mountain wine sped

through my veins, warming my fancy. Then, at last, the sun came out

in a sudden burst of light, opening a rift in the vapours and

revealing the whole chain of the Apennines, together with the

peaked crater of Mount Vulture.

The spectacle cheered

me, and led me to think that such a day might worthily be rounded

off by a visit to Sipontum, which lies a few miles beyond

Manfredonia on the Foggia road. But I approached the subject

cautiously, fearing that the coachman might demur at this extra

work. Far from it. I had gained his affection, and he would conduct

me whithersoever I liked. Only to Sipontum? Why not to

Foggia, to Naples, to the ends of the earth? As for the horse, he

was none the worse for the trip, not a bit the worse; he liked

nothing better than running in front of a carriage; besides,

è suo dovere--it was his duty.

Sipontum is so ancient

that it was founded, they say, by that legendary Diomed who acted

in the same capacity for Beneven-tum, Arpi, and other cities. But

this record does not satisfy Monsignor Sarnelli, its historian,

according to whom it was already a flourishing town when Shem,

first son of Noah, became its king. He reigned about the year 1770

of the creation of the world. Two years after the deluge he was 100

years old, and at that age begat a son Arfaxad, after whose birth

he lived yet another five hundred years. The second king of

Sipontum was Appulus, who ruled in the year 2213. . . . Later on,

Saint Peter sojourned here, and baptized a few people.

Of Sipontum nothing is

left; nothing save a church, and even that built only yesterday--in

the eleventh century; a far-famed church, in the Pisan style, with

wrought marble columns reposing on lions, sculptured diamond

ornaments, and other crafty stonework that gladdens the eye. It

used to be the seat

30 Old

Calabria

of an archbishopric,

and its fine episcopal chairs are now preserved at Sant' Angelo;

and you may still do homage to the authentic Byzantine Madonna

painted on wood by Saint Luke, brown-complexioned, long-nosed, with

staring eyes, and holding the Infant on her left arm. Earthquakes

and Saracen incursions ruined the town, which became wholly

abandoned when Manfredonia was built with its stones.

Of pagan antiquity

there are a few capitals lying about, as well as granite columns in

the curious old crypt. A pillar stands all forlorn in a field; and

quite close to the church are erected two others--the larger of

cipollino, beautified by a patina of golden lichen; a marble

well-head, worn half through with usage of ropes, may be found

buried in the rank grass. The plain whereon stood the great city of

Sipus is covered, now, with bristly herbage. The sea has retired

from its old beach, and half-wild cattle browse on the site of

those lordly quays and palaces. Not a stone is left. Malaria and

desolation reign supreme.

It is a profoundly

melancholy spot. Yet I was glad of the brief vision. I shall have

fond and enduring memories of that sanctuary--the travertine of its

artfully carven fabric glowing orange-tawny in the sunset; of the

forsaken plain beyond, full of ghostly phantoms of the

past.

As for Manfredonia--it

is a sad little place, when the south wind moans and mountains are

veiled in mists.

At Sipontum

V

LAND OF HORACE

VENOSA, nowadays, lies

off the beaten track. There are only three trains a day from the

little junction of Rocchetta, and they take over an hour to

traverse the thirty odd kilometres of sparsely inhabited land. It

is an uphill journey, for Venosa lies at a good elevation. They say

that German professors, bent on Horatian studies, occasionally

descend from those worn-out old railway carriages; but the ordinary

travellers are either peasant-folk or commercial gentlemen from

north Italy. Worse than malaria or brigandage, against both of

which a man may protect himself, there is no escaping from the

companionship of these last-named--these pathologically

inquisitive, empty-headed, and altogether dreadful people. They are

the terror of the south. And it stands to reason that only the most

incapable and most disagreeable of their kind are sent to

out-of-the-way places like Venosa.

One asks oneself

whether this town has greatly changed since Roman times. To be sure

it has; domestic calamities and earthquakes (such as the terrible

one of 1456) have altered it beyond recognition. The amphitheatre

that seated ten thousand spectators is merged into the earth, and

of all the buildings of Roman date nothing is left save a pile of

masonry designated as the tomb of the Marcellus who was killed here

by Hannibal's soldiery, and a few reticulated walls of the second

century or thereabouts known as the "House of Horace"--as genuine